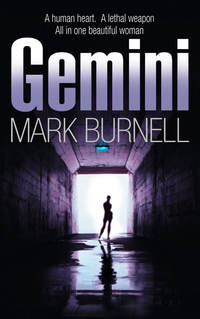

Gemini

GEMINI

Mark Burnell

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Mark Burnell 2003

Mark Burnell asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names,

characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the

author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons,

living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007152643

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2012 ISBN 9780007383061

Version: 2015-10-05

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Dedication

For Ivan with love

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Marrakech

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Marrakech

The first time I came to Marrakech I was a French tourist. I was also one half of a couple in love. Or so it must have seemed to those who saw us together. He was a lawyer from Milan, who told me that he’d been married but was now divorced. He never mentioned his second wife, though, or that she still considered their marriage idyllic, blessed, as it was, with three children, a house by Lake Como and a villa in Sardinia. Then again, I never mentioned that I intended to steal Russian SVR files from the wall-safe in his company apartment in Geneva. Or that having an affair with me might cost him his life.

Dishonesty was the blood that surged through the veins of our brief relationship. Without it there would have been no relationship. Without dishonesty I can never have a relationship because, after the truth, who in their right mind would have me?

The lawyer from Milan knew me as Juliette. The man who will meet me on the roof terrace of Café La Renaissance in seven minutes will know me as Petra Reuter. Around the world my face has many names, none of them real. Long ago, when I was a complete person – a single individual – I was someone called Stephanie Patrick. But almost nobody remembers her now.

Sometimes, not even me.

Dressed in black cotton trousers, a navy linen shirt and a pair of DKNY trainers, Petra Reuter crossed Avenue Mohammed V and took the lift to Café La Renaissance’s roof terrace, which overlooked Place Abdel Moumen ben Ali. Sprawled before her, Marrakech shimmered in the parching heat; eleven in the morning and it was already close to forty centigrade. She took off her sunglasses, swept long, dark hair from her eyes and was forced to squint. Above her the sky was deep sapphire, but the horizon remained bleached of colour. Beneath her, drowsy in the scorching breeze, the city murmured: the rasp of old engines, the squeal of a horn, of a shuddering halt, the bark of a dog from a nearby rooftop. She was surprised how much green there was among the terracotta and ochre, full trees throwing welcome shade onto baking pavements. She put her sunglasses back on.

There were some tables on the roof terrace with cheap metal chairs, their turquoise paint chipped and faded. At one table two soft, pear-shaped women were hunched over a map. Petra thought they sounded Canadian. At another table an elderly man in a crumpled grey suit sat in the shade, reading an Arabic newspaper. His walnut skin was peppered with shiny pink blotches. On a section of roof terrace overlooking Place Abdel Moumen ben Ali there were three large, red plastic letters hoisted on blue poles: b – a – r. Four French tourists were taking photographs of themselves with the reverse side of the letters as a backdrop.

Petra bought a Coke and sat at a secluded table. A fortnight had elapsed since her TGV had pulled into Marseille. She’d felt uneasy on that muggy afternoon, but she felt worse now. She’d arrived in Marseille from Ostend, via Paris. In Ostend she’d gone to the bar where Maxim Mostovoi had once been a regular. A charmless place with bright overhead lights and two dilapidated pool tables, one with a torn cloth. With a shrug of regret the proprietor said that Mostovoi hadn’t been in for at least six months; the traditional first line of defence. But Petra had come prepared, and a phrase contained within a question yielded an address in Paris: an apartment on the Rue d’Odessa in Montparnasse which, in turn, led to Marseille. From Marseille she’d travelled to Beirut, then Cairo. In Cairo two addresses – a Lebanese restaurant on Amman Street in Mohandesseen and a contemporary art gallery on Brazil Street in Zamalek – had finally delivered her to this rooftop terrace in Marrakech.

With each city, with each day, her suspicion hardened: that she was no closer to Mostovoi than she had been in Ostend. Or even in London, for that matter. Not that it made much difference. The pursuit might be pointless, but she knew that she would not be allowed to abandon it.

‘Petra Reuter.’

He’d lost weight. His hair was long, lank and greasy, greying at the temples. The whites of his bloodshot eyes were a sickly yellow, his skin waxy and loose. His red T-shirt hung limply from his skeletal frame, dark sweat stains marking points of contact. Creased linen trousers were secured by a purple tie threaded through the belt-loops. His fingers were trembling. Through cigarette smoke, Petra smelt decay.

She had only met Marcel Claesen twice before. The last time had been in a dacha outside Moscow. That had been less than two years ago, but the man in front of her appeared ten years older.

‘You look sick.’

‘Nice to know you haven’t lost your charm, Petra.’

‘Do you want to know what I really think?’

His feeble smile revealed toffee-coloured teeth. ‘It must be the water here. Or the food, maybe …’

‘Or the heat?’

He missed the subtext and shrugged. ‘Sure. Why not?’

‘What are you doing here?’

They sent me to make contact with you.’

Claesen, the Belgian intermediary. That was what he had been the first time they met. Then, as now, he’d radiated duplicity. He was a man who materialized in unlikely places for no specific reason, a man who didn’t actually do anything. Instead, he simply existed in the spaces between people. A conduit, Claesen was the stained banknote that hastened a seedy transaction.

He sat down opposite her and crossed one bony leg over the other. ‘Mostovoi thought it would be better to have a familiar face. You know, someone you could trust …’

Petra raised an eyebrow. ‘So he thought of you?’

He wiped the sweat from his brow with the heel of his hand, then shook his head and attempted another smile. ‘The things I’ve heard about you, Petra. They say you killed Vatukin and Kosygin in New York. They say you killed them for Komarov.’

‘How exciting.’

‘Others say you killed them for Dragica Maric. That the two of you are in love, each of you a reflection of the other.’

‘How imaginative.’

‘How true?’

‘You’d like that, wouldn’t you? The idea of me and another woman. Especially a woman like her.’

Claesen’s shrug was supposed to convey indifference but his eyes betrayed him. ‘You mean, a woman like you, don’t you?’

A black Land Cruiser Amazon with tinted windows was waiting for them at the kerb. Petra sat in the back, keeping Claesen and the driver in front of her. They headed for Palmeraie, to the north of the city centre, where extravagant villas were secreted in secure gardens. Most of the properties belonged to wealthy Moroccans, but in recent years there had been an influx of rich foreigners. At one of the larger walled compounds the driver pulled the Land Cruiser off the tarmac onto a dirt track. Ahead, heavy electric gates parted. Above them, two security cameras twitched.

Outside the compound the ground had been arid scrub between the palm trees. Inside it was lush lawn. Sprinklers sprayed a fine mist over the grass. Men tended flowerbeds, their backs bent to the overhead sun. On the right there were two floodlit tennis courts and a large swimming pool with a Chinese dragon carved from stone at each corner.

The villa was centrally air-conditioned and smelt like an airport terminal. There were two armed men in the entrance hall. Both were fair-skinned, their faces and arms burnt bright red. One carried a Browning BDA9, the other a Colt King Cobra. Without a word they led Claesen and Petra down a hall, the Belgian’s rubber soles squeaking on the veined marble floor. The room they entered had a thick white carpet, four armchairs – tanned leather stretched over chrome frames – positioned around a coffee table with a bronze horse’s head at its centre and, in one comer, an enormous Panasonic home entertainment system. Wooden blinds had been lowered over the windows. A curtain had been three-quarters drawn across a sliding glass door that opened onto a covered terrace. The door was partly open, allowing some natural air to infiltrate the artificial. Beyond the terrace she saw orange trees, lemon trees and perfectly manicured rose beds.

‘That’s far enough.’

He was sitting on the other side of the room, his back to the source of partial light, a man reduced to silhouette. Dark trousers, a white shirt, open at the neck, dark sunglasses. Petra was surprised he could even see her.

‘You want something to drink? Some tea? Or water?’

‘Nothing.’

There were two men to his right. The shorter and leaner of the two had a bony face like a whippet: a mean mouth with thin lips, a pointed nose, sharp little eyes. His hands were restless but his gaze was steady, never leaving her. With Claesen and the pair behind her, the men numbered six, two of them definitely armed.

‘Where’s Mostovoi?’

The man in the chair said, ‘Max has been detained.’

‘Detained?’

Incorrectly, he thought he detected anxiety in her tone. ‘Not in that sense of the word.’

‘I’m not interested in the sense of the word. If he’s not here, he’s not here.’

‘He sent me instead.’

‘And you are?’

‘Lars. Lars Andersen.’

Her eyes had adjusted to the lack of light. Andersen had short, dark, untidy hair, prominent cheekbones and olive skin that was lightly pockmarked; a Mediterranean look for a Scandinavian name, Petra thought.

‘No offence, Lars, but I don’t know you.’

‘You don’t know Max, either.’

‘I know what business he’s in. Which is why I’m here. But I’m starting to think I made a mistake. I’m running out of patience. That means he’s running out of time. It’s up to him. There are always others. Harding, Sasic, Beneix …’

‘They’re not as good.’

‘As good as what? A man who never shows? What could be worse than that?’

Andersen appeared surprised by her contempt. He glanced at the short one and said, in Russian, ‘What do you reckon, Jarni? Not bad, huh?’

‘Not bad.’

‘You think she could play for Inter?’

‘No problem.’

‘Where?’

‘Anywhere, probably. That’s what I hear.’

Also in Russian, Petra said, ‘What’s Inter?’

Raised eyebrows all round. Andersen said, ‘You speak Russian?’

‘Judging by your accents, better than either of you.’

Andersen grinned. ‘Max said we should be careful with you. Watch out for her, he told us, she’s full of surprises.’

Outside, a lawnmower started, its drone as nostalgic as the scent of the grass it cut. It reminded her of those summer evenings when her father, back from work, would mow their undulating garden. A childhood memory, then. But not Petra’s childhood. The memory belonged to someone else. Petra was merely borrowing it.

‘What’s Inter?’ she asked again.

‘You don’t know?’

‘Should I?’

He shrugged. ‘Inter Milan.’ When she made no comment, he returned to English. ‘You’ve never heard of Inter Milan?’

She shook her head.

‘The football team?’

The name was faintly resonant but she said, ‘I have better things to do with my time than watch illiterate millionaires kissing each other.’

‘Inter is more than a football team.’

‘Is there any danger of you straying towards the point?’

Andersen looked as though he wished to continue. He leaned forward and opened his mouth to speak – to protest, even – but then appeared to change his mind. An awkward silence developed. Petra sensed Claesen squirming behind her.

Eventually, Andersen said, ‘Tomorrow morning, the Mellah.’

‘Mostovoi will be there?’

‘Someone will be there. They’ll take you to him.’

‘If he’s not there I’m going home.’

‘Place des Ferblantiers at ten.’

The Land Cruiser drove her back to the city centre and came to a halt on Avenue Hassan II, just short of the intersection with Place du 16 Novembre. Claesen turned round. An inch of ash spilled down his red T-shirt. His creepy confidence had returned the moment they left the walled compound.

‘Until next time, then?’

‘How did they know that you knew me?’

‘I have no idea.’

‘You didn’t ask?’

‘I received a message, an air ticket and the promise of dollars.’

‘And that was enough for you? It never occurred to you to check it out first?’

His reply was bittersweet. ‘These days that’s a luxury I can’t afford.’

‘You know something, Claesen, I’m amazed you’ve made it this far.’

‘Me too.’ Smiling once more, he waved his Gitanes at her. ‘I used to think I’d never live long enough to die from lung cancer. Now I’m beginning to think I have a chance.’

The Hotel Mirage on Boulevard Mohammed Zerktouni was in the Ville Nouvelle, not far from Café La Renaissance. Mid-range, it mostly catered for European tourists. Which was precisely what Petra was: Maria Gilardini, a single Swiss woman, aged twenty-nine. A dental hygienist from Sion.

There was a message for her at reception. She took the envelope up to her room, at the rear of the building, overlooking a small courtyard, opposite the back of an ageing office block. She sat on the bed and opened the envelope. As expected, there was nothing inside.

Petra had heard of Maxim Mostovoi long before he became a contract. A former air force pilot, he’d emerged from the rubble of the Soviet Union with his own aviation business. His military career had been restricted to cargo transport. At the time, that had been a source of regret. Later it proved to be the source of his fortune.

Among the first to recognize potential markets for the Soviet Union’s vast stockpile of obsolete weaponry, Mostovoi was able to commandeer cargo aircraft from what remained of the Soviet air force. Then he formed partnerships with contacts in the army who were able to supply him with arms. In the early days he based himself in Moscow, taking comfort from the chaos that bloomed in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. There were few laws to contain him. Those that existed were not enforced; bribery tended to ensure that. Failing bribery, there was always violence.

Mostovoi’s first fortune was made in Africa. Rebel factions sought him out, eager for cheap weapons. Using huge Antonov cargo aircraft, he delivered to Rwanda, Angola and Sierra Leone, frequently taking payment in conflict diamonds, depositing the gems in Antwerp. Soon Mostovoi decided he would prefer to be closer to them. In 1994 he moved to Ostend, establishing an air freight company named Air Eurasia at offices close to the airport. As his reputation grew, so did demand for his services. He established an office in Kigali, the Rwandan capital, at the height of the genocide perpetrated by the Hutu militia. He bought a hotel in Kampala, in neighbouring Uganda. The top floor was converted into a luxury penthouse, marble flown in from Italy, bathrooms from Scandinavia, hookers from Moscow. Twice a year Unita rebels travelled from Angola to the hotel in Kampala with pouches of diamonds. The stones were valued by Manfred Hempel, a leading Manhattan diamond merchant, who was extravagantly rewarded for his time. Despite this, Hempel hated the trips to Uganda. To ease his discomfort Mostovoi used his Gulfstream V to ferry the diamond dealer directly from New York to Kampala and back again.

By 1996 his fleet of aircraft, mostly Antonovs and Illyushins, had grown to thirty-eight and had attracted the attention of the Belgian authorities. In December of that year he relocated Air Eurasia to Qatar, opening associate offices in Riyadh and the emirates of Ras al Khaimah and Sharjah. In February 1997 he met senior representatives of FARC – the Colombian rebel army – at San Vicente del Caguan, but failed to come to an agreement. From Colombia he travelled directly to Pakistan. In Peshawar he struck a deal to supply weapons to the Taliban in Afghanistan. Here he was paid in opium, which he sold for processing and onward distribution in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Born in Moscow in 1962, Mostovoi had been destined for mediocrity. An unexceptional pupil, a poor athlete, he longed to fly fighters for the Soviet air force but lacked the necessary skills, and was thus relegated to the cargo fleet. To those who knew him best, this would have seemed entirely predictable. As charming and amusing as he could be, it was accepted by everybody that Max would never amount to much. His wife used to tease him in public, and all Mostovoi would muster in his defence was a resigned shrug. Still, a decade and two hundred million dollars later, the memory of his heavy-hipped ex-wife had been eclipsed by the finest flesh money could buy. As a younger man he’d often dreamed of taking his revenge upon those who had humiliated him over the years. Now that he was in a position to do so, he found he couldn’t be bothered. He didn’t have the time. It was enough to know that he could.

Petra knew that had Mostovoi been content to confine his business interests to Africa, he would never have become the subject of a contract. The reality was that nobody cared about Africa. Afghanistan, however, was different. Through his relationship with the Taliban, Mostovoi was connected to al-Qaeda. Before 11 September 2001 he’d been an easy man to find, confident of his own security, keen to expand his empire. Since that date he’d been invisible.

Dusk descended quickly upon Djemaa el-Fna, the huge square in the medina that was the heart of Marrakech. Kerosene lamps replaced the daylight, strung out along rows of food stalls.

Petra found the café on the edge of the square. The outdoor tables were mostly taken. Inside, she picked a table with a clear view of the entrance. A slowly rotating fan barely disturbed the hot air. To her right, beneath an emerald green mosaic of the Atlas mountains, two elderly men were in animated discussion over glasses of tea.

She ordered a bottle of mineral water and drank half of it, checking the entrance as often as she checked her watch. At ten past seven she got up and asked the man behind the bar for the toilet. Past the cramped, steaming kitchen she came to a foul-smelling cubicle, which she ignored, pressing on down the dim corridor to the door at the end, which was shut. She tried the handle and it opened, as promised. She found herself in a narrow alley, rubble underfoot. At the end of the alley she saw the lane that she’d identified on the town map. She unbuttoned her shirt, took it off, turned it inside out and put it back on, trading powder blue for plum.

At twenty-five past seven she emerged from a small street on the opposite side of Djemaa el-Fna to the café. This time she melted into the crowd at the centre of the square, trawling the busy stalls, until she found one with no customers. She sat on a wooden bench beneath three naked bulbs hung from a cord sagging between two poles. The man on the other side of the counter was tending strips of lamb on an iron rack, fat spitting on the coals, smoke spiralling upwards, adding to the heat of the night. Petra passed fifteen dirhams across the counter for a small bowl of harira, a spicy lentil soup.

The woman appeared within five minutes, a child in tow. Short, dark and squat, she wore a dark brown ankle-length dress and a flimsy cotton shawl around her shoulders. The child had black curls, caramel skin, pale hazel eyes. She was eating dried fruit. They sat on the bench to Petra’s right. The woman ordered two slices of melon, which the man retrieved from a crate behind him.

In French, she said, ‘Someone was in your hotel room today. A man.’

Petra nodded. ‘What was he doing?’

‘Looking.’

‘Did he find anything?’

‘It’s not possible to say. He spent most of his time with your laptop. I think he might have downloaded something. It wasn’t easy to see. The angle was awkward.’

‘From across the courtyard?’

The woman shook her head. ‘That view was too restricted. I had to try something else. A camera concealed in the smoke detector.’

‘I hadn’t noticed there was a smoke detector.’

‘Above the door to your bathroom. It’s cosmetic. A plastic case to satisfy a safety regulation. Actually, I’m surprised. A bribe is easier and cheaper.’

‘Where was the base unit?’

‘Across the courtyard. In the office.’ The woman finished a mouthful of melon. ‘He went through your clothes, your personal belongings. He took care to replace everything as he found it. He searched under the bed, behind the drawers, on top of the cupboard. All the usual hiding places. You have a gun?’

‘Not there. Anything else?’

‘A Lear jet arrived at Menara Airport early this morning. A flight plan has been filed for tomorrow afternoon. Stern wants you to know that Mostovoi has a meeting in Zurich tomorrow evening.’

I lie on my bed, naked and sweating. When I came to Marrakech with Massimo, the lawyer from Milan, we stayed at the Amanjena, a cocoon of luxury on the outskirts of the city. There we indulged ourselves fully. On our last evening we ate at Yacout, a palace restaurant concealed within a warren of tiny streets. We drank wine on the roof terrace while musicians played in the corner. A hot breeze blew through us. Mostly, I remember the view of the city by night, lights sparkling like gemstones against the darkness. Later we ate downstairs in a small courtyard with rose petals on the floor. That was where Massimo took my hand and said, ‘Juliette, I think I’m falling in love with you.’