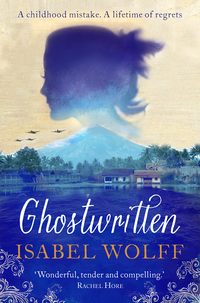

Ghostwritten

Jon’s parents went to their seats. Behind them I recognised a colleague of Nina’s, and now here was Honor, in a green ‘bombshell’ dress that hugged her curves and complemented her creamy skin and blonde hair. She blew me and Rick an extravagant kiss then sat near the front.

Now Jon and his older brother, James, took their places together, while their younger brother, Tim, ushered in a few latecomers. Nina’s mother, in a turquoise opera coat and matching hat, smiled benignly as she made her way to her pew.

I turned and caught a glimpse of Nina. She stood in the porch, in the white silk dupion sheath that Honor and I had helped her choose, her veil drifting behind her.

As the Bach drew to an end, the vicar stepped in front of the altar and welcomed everyone. Then there was a burst of Handel, and we all stood as Nina walked down the aisle on her father’s arm.

After the opening prayers we sang ‘Morning Has Broken’; then Honor stepped up to the lectern to read the sonnet that Nina had chosen.

‘My true love hath my heart, and I have his,’ she began, her dulcet voice echoing slightly. ‘By just exchange one for the other given. I hold his dear, and mine he cannot miss. There never was a better bargain driven …’

As Honor read on, I felt a sting of envy. The lovers understood each other so well. I thought I’d had that with Rick …

‘My true love hath my heart – and I have his,’ Honor concluded.

The vicar raised his hands. ‘Dearly beloved, we are gathered together here in the sight of God, and in the face of this congregation, to join together this Man and this Woman in holy Matrimony …’ I looked at Nina and Jon, side by side in a pool of light, and wondered whether these words would ever be said for Rick and me. ‘Nor taken in hand wantonly,’ the vicar was saying, ‘but reverently, discreetly, advisedly and soberly, and in the fear of God, duly considering the causes for which Matrimony was ordained.’ At that I felt Rick shift slightly. ‘First, it was ordained for the procreation of children …’ I stole a glance at him, but his face gave nothing away. ‘Therefore, if any man can show any just cause, why they may not lawfully be joined together, let him now speak, or else, hereafter, forever hold his peace.’

I tried to follow the service but found it suddenly impossible to focus on the music, or the Address, or on the beauty and solemnity of the vows. As Nina and Jon committed themselves to each other, with unfaltering voices, I felt another stab of pain. The register was signed, the last hymn sung and the blessing given; then, as Widor’s Toccata mingled with the pealing bells, we followed Nina and Jon outside.

We showered the couple with petals and took snaps with our phones; then the photographer began the formal photos of them while we all milled around by the porch.

‘Great to see you! Fantastic weather!’

‘Lovely service – much prefer the King James.’

‘Me too. Well read, Honor!’

‘Should we make our way to the house?’

‘Not yet. I think they want a group pic.’

Rick and I, keen to get away from the crowd, strolled through the churchyard; we looked at the gravestones, most of which were very old and eroded, blotched with yellow lichen.

Rick stopped in front of a slate headstone. ‘That’s odd. It’s got a pineapple on it.’

I looked at the carved image. ‘A pineapple means prosperity, as do figs, and I guess this was a prosperous area, probably because of the wool trade.’

We walked on, in silence, past stones that had angels on them, and doves and candles, the symbolism of which was clear.

We could hear the chatter of the guests, a sudden burst of Honor’s unmistakeable laughter, then the photographer’s voice. Could you look at me, Nina?

Rick approached another grave, by a yew. He peered at it. ‘This one’s got a bunch of grapes carved on it.’

‘Grapes represent the wine at the Last Supper.’

Rick glanced at me. ‘How do you know all this, Jen? I didn’t think you were religious.’

‘I had to research it for one of my books. It was years ago, but I’ve remembered a lot of it.’

Now look at each other again …

‘Here’s a rose,’ Rick said, pointing to another headstone. ‘I assume that means love?’

Oh, very romantic …

‘No. Roses show how old the person was when they died.’ I studied the worn emblem. ‘This is a full rose, which was used for adults.’ I read the inscription. ‘Mary Ann Betts … was …’ I peered at her dates. ‘Twenty-five. The stem’s severed, to show that her life was cut short.’

‘I see …’ Our conversation felt stiff and formal, as though we were strangers, not lovers.

Can we have a kiss?

‘A partially opened rose means a teenager.’

And another one. Lovely.

‘And a rosebud is for a child.’

Hold his hand now.

Rick nodded thoughtfully. ‘A sad subject.’

‘Yes …’ Okay, all stand together, please – nice and close!

Rick and I rejoined everyone for the group photo, for which the photographer climbed onto a stepladder, wobbling theatrically to make us all laugh. We smiled up at him while he clicked away then, hand in hand, Nina and Jon led us down the path, across the field, to the house.

The Old Forge was just as I remembered it – long and low, its pale stone walls ablaze with pyracantha and Virginia creeper. A large marquee filled the lawn. In the distance were the hills of Slad, the plunging pastures dotted with sheep, their bleats carrying across the valley on the still air.

We joined the receiving line, greeting both sets of parents, then the bride and groom.

Nina’s face lit up and we hugged. ‘Jenni …’

I had to fight back sudden tears. I didn’t know whether they were tears of happiness for her or of self-pity. ‘You look so beautiful, Nina.’

‘Thank you.’ She put her lips to my ear. ‘You next,’ she whispered.

Jon kissed me on the cheek, then clasped Rick’s hand. ‘Good to see you both! Thanks for coming!’

‘Congratulations, Jon,’ Rick said warmly. ‘It was a lovely service. Congratulations, Nina.’

Now we moved on into the large sunny sitting room where drinks were being served. I put our gift on a table amongst a cluster of other presents and cards. A waiter offered us a glass of champagne. Rick raised his glass. ‘Here’s to the happy couple.’

‘They are happy’ – I sipped my fizz. ‘It’s wonderful.’

‘How long have they been together?’

‘About the same as us. They got engaged on their first anniversary,’ I added neutrally, then laughed at myself for ever having thought that Rick and I might do the same.

I looked at Rick, so handsome, with his open face, short dark hair and blue gaze. I tried, and failed, to imagine life without him. We’d agreed to talk things over again the next day. Before I could think about that, though, a gong summoned us into the marquee, which was bedecked with white agapanthus and pink nerines, the tables gleaming with silver and china. We found our names, standing behind our chairs while the vicar said Grace.

Rick and I had been placed with Honor, and with Amy and Sean, whom I’d known at college but hadn’t seen for years, and an old schoolfriend of Jon’s, Al. I was glad that Nina had put him next to Honor; she’d been single for a while now, and he was very attractive. Also on our table was Nina’s godfather, Vincent Tregear. I vaguely remembered him from her twenty-first birthday. A near neighbour named Carolyn Browne introduced herself. I steeled myself for the effort of making small talk with people I don’t know; unlike Honor, I’m not good at it, and in my present frame of mind it would be harder than usual.

I heard Carolyn explain to Rick that she was a solicitor, recently retired. ‘I’m so busy though,’ she confessed, laughing. ‘I’m a governor of a local school, I play golf and bridge; I travel. I was dreading retirement, but it’s really fine.’ She smiled at Rick. ‘Not that you’re anywhere near that stage. So, what do you do?’

He unfurled his napkin. ‘I’m a teacher – at a primary school in Islington.’

‘He’s the deputy head,’ I volunteered, proudly.

Carolyn smiled at me. ‘And what about you, erm …?’

‘Jenni.’ I turned my place card towards her.

‘Jenni,’ she echoed. ‘And you’re …’ She nodded at Rick.

‘Yes, I’m Rick’s …’ The word ‘girlfriend’ made us seem like teenagers; ‘partner’ made us sound as though we were in business, not in love. ‘Other half,’ I concluded, though I disliked this too: it seemed to suggest, ominously, that we’d been sliced apart.

‘And what do you do?’ Carolyn asked me.

My heart sank – I hate talking about myself. ‘I’m a writer.’

‘A writer?’ Her face had lit up. ‘Do you write novels?’

‘No,’ I replied. ‘It’s all non-fiction. But you won’t have heard of me.’

‘I read a lot, so maybe I will. What’s your name? Jenni …’ Carolyn peered at my place card. ‘Clark.’ She narrowed her eyes. ‘Jenni Clark …’

‘I don’t write under that name.’

‘So is it Jennifer Clark?’

‘No – what I mean is, I don’t write under any name.’ I was about to explain why, when Honor said, ‘Jenni’s a ghost.’

‘A ghost?’ Carolyn looked puzzled.

‘She ghosts things.’ Honor unfurled her napkin. ‘Strange to think that it can be a verb, isn’t it? I ghost, you ghost, he ghosts,’ she added gaily.

I rolled my eyes at Honor, then turned to Carolyn. ‘I’m a ghostwriter.’

‘Oh, I see. So you write books for people who can’t write.’

‘Or they can,’ I said, ‘but don’t have the time, or lack the confidence, or they don’t know how to shape the material.’

‘So it’s actors and pop stars, I suppose? Footballers? TV presenters?’

I shook my head. ‘I don’t do the celebrity stuff – I used to, but not any more.’

‘Which is a shame,’ Honor interjected, ‘as you’d make far more money.’

‘True.’ I rested my fork. ‘But I didn’t enjoy it.’

‘Why not?’ asked Al, who was on my left.

‘It was too frustrating,’ I answered, ‘having to battle with my subjects’ egos, or finding that they didn’t turn up for the interviews; or that they’d give me some brilliant material then the next day tell me that I wasn’t to use it. So these days I only do the projects that interest me.’

Honor, who has a butterfly mind, was now discussing ghosts of the other kind. ‘I’m sure they exist,’ she said to Vincent Tregear. ‘Twenty years ago I was staying with my cousins in France; it was a warm, still day, just like today, and we were exploring this abandoned house. It was a ruin, so we could see right up to the roof … And we both heard footsteps, right above us, on the non-existent floorboards.’ She gave an extravagant shudder. ‘I’ve never forgotten it.’

‘I believe in ghosts,’ Carolyn remarked. ‘I live on my own, in an old house, and at times I’ve been aware of this … presence.’

Amy nodded enthusiastically. ‘I’ve sometimes felt a sudden chill.’ She turned to Sean. ‘Do you remember, darling, last summer? When we were in Wales?’

‘I do,’ he answered. ‘Though I believe it was because you were pregnant.’

‘No: pregnancy made me feel hot, not cold.’

‘A few years ago,’ said Al, ‘I was asleep in my flat, alone, when I suddenly woke up, convinced that someone was sitting on my bed.’

I shivered at the idea. ‘And you weren’t dreaming?’

He shook his head. ‘I was wide awake. I can still remember the weight of it, pressing down on the mattress. Yet there was no one there.’

‘How terrifying,’ I murmured.

‘It was.’ He poured me some water then filled his own glass. ‘Has anything like that ever happened to you?’

‘It hasn’t, I’m glad to say. But I don’t dismiss other people’s experiences.’

‘I’ve always been sceptical about these things,’ Sean observed. ‘I believe that if people are sufficiently on edge they can see things that aren’t really there. Like Macbeth seeing the ghost of Banquo.’

‘Shake not thy gory locks at me!’ intoned Honor, then giggled. ‘And Macbeth certainly is on edge by then, isn’t he, having murdered – what – four people?’ Then she went off on some new conversational tangent about why it was considered unlucky for actors to say ‘Macbeth’ inside a theatre. ‘People think it’s because of the evil in the story,’ she prattled away as a waiter took her plate. ‘But it’s actually because if a play wasn’t selling well, the actors would have to quickly rehearse Macbeth as that’s always popular, so doing Macbeth became associated with ill luck. Now … what are we having next?’ She picked up a gold-tasselled menu. ‘Sea bass – yum. Did you know that sea bass are hermaphrodites? The males become females at six months.’

Al, clearly uninterested in the gender-switching tendencies of our main course, turned to me. ‘So what sort of books do you write?’

‘A real mix,’ I answered. ‘Psychology, health and popular culture; I’ve done a diet book, and a couple of gardening books …’

I thought of my titles, more than twenty of them, lined up on the shelf in my study.

‘So you must learn a huge amount about all these things,’ Al said.

‘I do. It’s one of the perks.’

Carolyn sipped her wine. ‘But do you get any kind of credit?’

‘No.’

‘I thought that with ghostwritten books it usually said “with” so-and-so or “as told to”.’

‘It depends,’ I said. ‘Some ghostwriters ask for that. I don’t.’

‘So your name appears nowhere?’

‘That’s right.’

She frowned. ‘Don’t you mind?’

I shrugged. ‘Anonymity’s part of the deal. And of course the clients like it that way. They’d prefer everyone to think they’d written the book all by themselves.’

Carolyn laughed. ‘I couldn’t bear not to have any of the glory. If I’d worked that hard on something, I’d want people to know!’

‘Me too,’ chimed in Honor. ‘I don’t know why you want to hide your light under a bushel quite so much, Jen.’

‘Because it’s enough that I’ve enjoyed the work and been paid for it. I’m happy to be … invisible.’

‘You were always like that,’ Honor went on. ‘You were never one to seek the limelight – unlike me,’ she giggled. ‘I enjoy it.’

‘So are you still acting?’ Sean asked her.

‘Not for five years now,’ she answered. ‘I couldn’t take the insecurity any more, so I went into radio, which I love.’

‘I’ve heard your show,’ Amy interjected. ‘It’s really good.’

‘Thanks.’ Honor basked in the compliment for a moment. ‘And you two have had a baby, haven’t you?’

‘We have,’ Amy answered. ‘So I’m on maternity leave …’

‘And what are you working on now, Jenni?’ Carolyn asked.

I fiddled with my wine glass. ‘A baby-care guide.’

‘How lovely,’ she responded. ‘And are you a mum?’

My heart contracted. ‘No.’ I sipped my wine.

‘Doesn’t that make it difficult? Writing a book about something you haven’t been through yourself?’

‘Not at all. The client’s talked extensively to me about her experience – she’s a midwife – and I’ve written it up in a clear and, I hope, engaging way.’

‘I must buy it,’ Amy said to me. ‘What’s it called?’

‘Bringing Up Baby. It’ll be out in the spring. But I always get given a few complimentary copies, so if you give me your address I’ll send you one.’

‘Oh, that’s kind. I’ll write it down …’ Amy began looking in her bag for a pen.

‘You can contact me through my website,’ I suggested. ‘Jenni Clark Ghostwriting. So … how old’s your baby?’

At that Sean took out his phone and swiped the screen. ‘She’s called Rosie.’

I smiled at the photo. ‘She’s gorgeous. Isn’t she lovely, Honor?’

Honor peered at the image. ‘She’s a little beauty.’

‘She’s what, six months?’ I asked.

Amy’s face glowed with pride. ‘Yes – she’ll be seven months a week on Wednesday.’

‘So is she crawling?’ I went on, ‘Or starting to roll over?’ Beside me I could feel Rick stiffen.

‘She’s crawling beautifully,’ Amy replied. ‘But she’s not rolling over yet.’

Sean laughed. ‘It’ll be nerve-wracking when she does.’

‘You won’t be able to leave her on the bed or the changing table,’ I said. ‘That’s when lots of parents put the changing mat on the floor – not that I’m a parent myself, but of course we cover this in the book …’ Rick had tuned out of the conversation and was talking to Carolyn again. Al turned to me. ‘So can you write about any subject?’

‘Well, not something I could never relate to,’ I answered, ‘like particle physics – not that I’d ever get chosen for a book like that. But I’ll do almost any professional writing job: corporate reports, press releases, business pitches, memoirs …’

‘Memoirs?’ echoed Vincent Tregear. ‘You mean, writing someone’s life story?’

‘Yes – usually an older person, just for private publication.’

‘Do you enjoy that?’ Vincent wanted to know.

‘Very much. In fact it’s the best part of the job. I love immersing myself in other people’s memories.’

Vincent looked as though he was about to say something, but then Carolyn began asking him about golf, Amy was telling Rick about yoga, and Honor was chatting to Al about his work as an orthodontist. She was drawn to him, I could tell. Good old Nina for putting them together. Suddenly Honor looked at me, grinned, then tapped her teeth. ‘Al says I have a perfect bite.’

I raised my glass. ‘Congratulations!’

‘Not just good,’ Honor said. ‘Perfect!’

‘Don’t let it go to your head,’ Al said.

She laughed. ‘Where else is my bite supposed to go?’

Soon it was time for the speeches and toasts; the cake was cut, then after coffee there was a break before the evening party was to start.

Amy and Sean had to leave, to get back to their baby. Vincent Tregear also said his goodbyes. As the caterers moved back the tables, Rick and I went out into the garden.

We sat on a bench, watching the sky turn crimson, then mauve, then an inky blue in which the first stars were starting to shine.

‘Well … it’s been a great day,’ Rick pronounced. The awkwardness had returned, squatting between us like an uninvited guest.

‘It’s been a lovely day,’ I agreed. ‘We should …’

‘What?’ he murmured.

My nerve failed. ‘We should go inside. It’s getting cold.’

Rick stood up. ‘And the band’s started.’ He held out his hand.

So we returned to the marquee where Jon and Nina were dancing their first waltz. Soon everyone took to the floor. But as Rick’s arms went round me and he pulled me close, I felt that he was hugging me goodbye.

TWO

‘So … what are we going to do?’ Rick asked me gently the following day.

We’d had lunch – not that I’d been able to eat – and now faced each other across our kitchen table. I shook my head, helplessly. I didn’t trust myself to speak.

‘We’ve got three options,’ Rick went on. ‘One, I change my mind; two, you change your mind; or three …’

I felt my stomach clench. ‘I don’t want to break up.’

‘Nor do I.’ Rick exhaled, hard, as though breathing on glass, then he looked at me, his blue eyes searching my face. ‘I do love you, Jen.’

‘Then you should be happy to let me have what I want.’

He flinched. ‘You know it’s not that simple.’

A silence fell in which we could hear the rumble of traffic from the City Road.

‘I keep thinking about this quote I once read,’ Rick said after a moment. ‘I can’t remember who it’s by, but it’s about how love doesn’t consist in gazing at the other person, but in looking together in the same direction.’ He shrugged. ‘But we’re not doing that.’

I cradled my coffee mug with its pattern of red hearts. ‘We’ve been together for a year and a half,’ I said quietly. ‘We’ve lived together for nine months, and we’ve been happy. Haven’t we?’ I glanced at the framed photo collage that I’d made of our first year together. There were snaps of us on top of Mount Snowdon, walking on the South Downs, sitting on the swing seat in his parents’ garden, cooking together, kissing. Then my eyes strayed to Nina’s wedding invitation on the kitchen dresser. I bitterly regretted having teasingly asked Rick when we might take our relationship forward.

‘We have been happy,’ Rick said at last. ‘That’s what makes it so hard.’

Another silence enveloped us. I could hear the hum of the fridge. ‘There is a fourth option,’ I said, ‘which is to go on as we were. So let’s just … forget marriage.’

Rick stared at me as though I were speaking in tongues. ‘This isn’t about marriage, Jen.’

I glanced at my manuscript, the typed pages stacked up on the table. Bringing Up Baby. From Newborn to 12 Months, the Definitive Infant-Care Guide. A page had fallen to the floor.

‘So what are we going to do?’ Rick asked me again.

‘I don’t know.’ A wave of resentment coursed through me. ‘I only know that I was always honest with you.’ As I picked up the sheet, random sentences leapt out at me. Great adventure of parenthood … bliss of holding your baby for the first time … what to expect, month by month.

‘You were honest.’ Rick nodded. ‘You told me right from the start that you didn’t want to have children and that this was something I had to know if we were to get involved.’

‘Yes,’ I said hotly, ‘and you said you didn’t mind, because you work with children every day. You said that your brother has four kids, so there was no pressure on you to have them. You told me that you’d never been bothered about it and that people can have a good life without children – which is true.’

‘I did feel like that, Jenni. But I’ve changed.’

‘Well, I wish you hadn’t, because now we’ve got a problem.’

Rick pushed back his chair; he went and stood by the French windows. Through the panes the plants in our small walled garden looked dusty and withered. I’d been too distracted and upset to water them. ‘People do change,’ he said quietly. ‘They’re allowed to change. And it’s crept up on me over the past few months. I’ve wanted to talk to you about it but was afraid to, precisely for this reason, but now you’ve brought the issue into the open.’

‘Why have you changed?’

He shrugged. ‘I don’t know – probably because I’m nearly forty now.’

‘You were nearly forty when we met.’

‘Or maybe it’s seeing the kids at school develop and grow, and wishing that I could watch my own kids do that.’

‘That didn’t seem to worry you before.’

‘True. But now it does.’

I glanced at the manuscript. ‘I think it’s because I’ve been working on this baby-care book.’ I felt my throat constrict. ‘I wish I’d never agreed to do it.’

‘The book has nothing to do with it, Jen. I wanted to be with you so much that I convinced myself I didn’t want children. Then I began to believe that because we were in love we’d naturally want to have them. So I thought you’d change your mind.’

‘Which is what you’re hoping for now?’

Rick sighed. ‘I guess I am. Because then we’d still have each other, but with the chance of family life too. I’ll be applying for head teacher posts before long: I’d like to try for jobs outside London, if you were happy to move.’

‘I’d be happy to be wherever you were,’ I said truthfully.

‘Jen …’ Rick’s face was full of sudden yearning. ‘We could have a great life: we’d be able to afford a bigger place.’ He looked around him. ‘This flat’s so small.’

‘I don’t care. I’d live in a bedsit with you if I had to. But, yes, it would be wonderful to have more space – with a bigger garden.’

He nodded. ‘I’ve been thinking about that garden a lot. I see a lawn, with children running around on it, laughing. But then they fade, like ghosts, because I know you don’t want any.’ Rick sat down again, then reached for my hands. ‘I want nothing more than to share my life with you, Jen, but we have to want the same things. And the question of whether or not we have children isn’t one that we can compromise on; and if we can’t agree about it—’