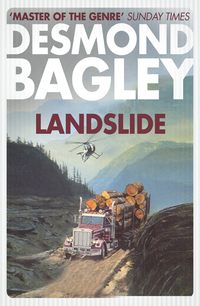

Landslide

‘So?’

‘Son, have you seen this man?’

I looked down at the photograph again. Grant looked to be only a boy, barely in his twenties and with a fine full life ahead of him. I said slowly, ‘To my best knowledge I’ve never seen that face.’

‘Well, it was a try,’ said McDougall. ‘I had thought you might be a friend of his come to see how the land lies.’

‘I’m sorry, Mac,’ I said. ‘I’ve never met this man. But why would he want to come here, anyway? Isn’t Grant an irrelevancy?’

‘Maybe,’ said McDougall thoughtfully. ‘And maybe not. I just wanted to talk to him, that’s all.’ He shrugged. ‘Let’s have another drink, for God’s sake!’

That night I had the Dream. It was at least five years since I had had it last and, as usual, it frightened hell out of me. There was a mountain covered with snow and with jagged black rocks sticking out of the snow like snaggle teeth. I wasn’t climbing the mountain or descending – I was merely standing there as though rooted. When I tried to move my feet it was as though the snow was sticky like an adhesive and I felt like a fly trapped on flypaper.

The snow was falling all the time; drifts were building up and presently the snow was knee-high and then at midthigh. I knew that if I didn’t move I would be buried so I struggled again and bent down and pushed at the snow with my bare hands.

It was then that I found that the snow was not cold, but red hot in temperature, even though it was perfectly white in my dreams. I cried in agony and jerked my hands away and waited helplessly as the snow imperceptibly built up around my body. It touched my hands and then my face and I screamed as the hot, hot snow closed about me burning, burning, burning …

I woke up covered in sweat in that anonymous hotel room and wished I could have a jolt of Mac’s fine Islay whisky.

TWO

The first thing I can ever remember in my life is pain. It is not given to many men to experience their birth-pangs and I don’t recommend it. Not that any commendation of mine, for or against, can have any effect – none of us chooses to be born and the manner of our birth is beyond our control.

I felt the pain as a deep-seated agony all over my body. It became worse as time passed by, a red-hot fire consuming me. I fought against it with all my heart and seemed to prevail, though they tell me that the damping of the pain was due to the use of drugs. The pain went away and I became unconscious.

At the time of my birth I was twenty-three years old, or so I am reliably informed.

I am also told that I spent the next few weeks in a coma, hovering on that thin marginal line between life and death. I am inclined to think of this as a mercy because if I had been conscious enough to undergo the pain I doubt if I would have lived and my life would indeed have been short.

When I recovered consciousness again the pain, though still crouched in my body, had eased considerably and I found it bearable. Less bearable was the predicament in which I found myself. I was spreadeagled – tied by ankles and wrists – lying on my back and apparently immersed in liquid. I had very little to go on because when I tried to open my eyes I found that I couldn’t. There was a tightness about my face and I became very much afraid and began to struggle.

A voice said urgently, ‘You must be quiet. You must not move. You must not move.’

It was a good voice, soft and kind, so I relaxed and descended into that merciful coma again.

A number of weeks passed during which time I was conscious more frequently. I don’t remember much of this period except that the pain became less obtrusive and I became stronger. They began to feed me through a tube pushed between my lips, and I sucked in the soups and the fruit juices and became even stronger. Three times I was aware that I had been taken to an operating theatre; I learned this not from my own knowledge but by listening to the chatter of nurses. But for the most part I was in a happy state of thoughtlessness. It never occurred to me to wonder what I was doing there or how I had got there, any more than a newborn baby in a cot thinks of those things. As a baby, I was content to let things go their own way so long as I was comfortable and comforted.

The time came when they cut the bandage from my face and eyes. A voice, a man’s voice I had heard before, said, ‘Now, take it easy. Keep your eyes closed until I tell you to open them.’

Obediently I closed my eyes tightly and heard the snip of the scissors as they clipped through the gauze. Fingers touched my eyelids and there was a whispered, ‘Seems to be all right.’ Someone was breathing into my face. The voice said, ‘All right; you can open them now.’

I opened my eyes to a darkened room. In front of me was the dim outline of a man. He said, ‘How many fingers am I holding up?’

A white object swam into vision. I said, ‘Two.’

‘And how many now?’

‘Four.’

He gave a long, gusty sigh. ‘It looks as though you are going to have unimpaired vision after all. You’re a very lucky young man, Mr Grant.’

‘Grant?’

The man paused. ‘Your name is Grant, isn’t it?’

I thought about it for a long time and the man assumed I wasn’t going to answer him. He said, ‘Come now; if you are not Grant, then who are you?’

It is then they tell me that I screamed and they had to administer more drugs. I don’t remember screaming. All I remember is the awful blank feeling when I realized that I didn’t know who I was.

I have given the story of my rebirth in some detail. It is really astonishing that I lived those many weeks, conscious for a large part of the time, without ever worrying about my personal identity. But all that was explained afterwards by Susskind.

Dr Matthews, the skin specialist, was one of the team which was cobbling me together, and he was the first to realize that there was something more wrong with me than mere physical disability, so Susskind was added to the team. I never called him anything other than Susskind – that’s how he introduced himself – and he was never anything else than a good friend. I guess that’s what makes a good psychiatrist. When I was on my feet and moving around outside hospitals we used to go out and drink beer together. I don’t know if that’s a normal form of psychiatric treatment – I thought head-shrinkers stuck pretty firmly to the little padded seat at the head of the couch – but Susskind had his own ways and he turned out to be a good friend.

He came into the darkened room and looked at me. ‘I’m Susskind,’ he said abruptly. He looked about the room. ‘Dr Matthews says you can have more light. I think it’s a good idea.’ He walked to the window and drew the curtains. ‘Darkness is bad for the soul.’

He came back to the bed and stood looking down at me. He had a strong face with a firm jaw and a beak of a nose, but his eyes were incongruously soft and brown, like those of an intelligent ape. He made a curiously disarming gesture, and said, ‘Mind if I sit down?’

I shook my head so he hooked his foot on a chair and drew it closer. He sat down in a casual manner, his left ankle resting on his right knee, showing a large expanse of sock patterned jazzily and two inches of hairy leg. ‘How are you feeling?’

I shook my head.

‘What’s the matter? Cat got your tongue?’ When I made no answer he said, ‘Look, boy, you seem to be in trouble. Now, I can’t help you if you don’t talk to me.’

I’d had a bad night, the worst in my life. For hours I had struggled with the problem – who am I? – and I was no nearer to finding out than when I started. I was worn out and frightened and in no mood to talk to anyone.

Susskind began to talk in a soft voice. I don’t remember everything he said that first time but he returned to the theme many times afterwards. It went something like this:

‘Everyone comes up against this problem some time in his life; he asks himself the fundamentally awkward question: ‘Who am I?’ There are many related questions, too, such as, ‘Why am I?’ and ‘Why am I here?’ To the uncaring the questioning comes late, perhaps only on the death-bed. To the thinking man this self-questioning comes sooner and has to be resolved in the agony of personal mental sweat.

‘Out of such self-questioning have come a lot of good things – and some not so good. Some of the people who have asked these questions of themselves have gone mad, others have become saints, but most of us come to a compromise. Out of these questions have arisen great religions. Philosophers have written too many books about them, books containing a lot of undiluted crap and a few grains of sense. Scientists have looked for the answers in the movement of atoms and the working of drugs. This is the problem which exercises all of us, every member of the human race, and if it doesn’t happen to an individual then that individual cannot be considered to be human.

‘Now, you’ve bumped up against this problem of personal identity head-on and in an acute form. You think that just because you can’t remember your name you’re a nothing. You’re wrong. The self does not exist in a name. A name is just a word, a form of description which we give ourselves – a mere matter of convenience. The self – that awareness in the midst of your being which you call I – is still there. If it weren’t, you’d be dead.

‘You also think that just because you can’t remember incidents in your past life your personal world has come to an end. Why should it? You’re still breathing; you’re still alive. Pretty soon you’ll be out of this hospital – a thinking, questioning man, eager to get on with what he has to do. Maybe we can do some reconstructions; the odds are that you’ll have all your memories back within days or weeks. Maybe it will take a bit longer. But I’m here to help you do it. Will you let me?’

I looked up at that stern face with the absurdly gentle eyes and whispered, ‘Thanks.’ Then, because I was very tired, I fell asleep and when I woke up again Susskind had gone.

But he came back next day. ‘Feeling better?’

‘Some.’

He sat down. ‘Mind if I smoke?’ He lit a cigarette, then looked at it distastefully. ‘I smoke too many of these damn’ things.’ He extended the pack. ‘Have one?’

‘I don’t use them.’

‘How do you know?’

I thought about that for fully five minutes while Susskind waited patiently without saying a word. ‘No,’ I said. ‘No, I don’t smoke. I know it.’

‘Well, that’s a good start,’ he said with fierce satisfaction. ‘You know something about yourself. Now, what’s the first thing you remember?’

I said immediately, ‘Pain. Pain and floating. I was tied up, too.’

Susskind went into that in detail and when he had finished I thought I caught a hint of doubt in his expression, but I could have been wrong. He said, ‘Have you any idea how you got into this hospital?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I was born here.’

He smiled. ‘At your age?’

‘I don’t know how old I am.’

‘To the best of our knowledge you’re twenty-three. You were involved in an auto accident. Have you any ideas about that?’

‘No.’

‘You know what an automobile is, though.’

‘Of course.’ I paused. ‘Where was the accident?’

‘On the road between Dawson Creek and Edmonton. You know where those places are?’

‘I know.’

Susskind stubbed out his cigarette. ‘These ash-trays are too damn’ small,’ he grumbled. He lit another cigarette. ‘Would you like to know a little more about yourself? It will be hearsay, not of your own personal knowledge, but it might help. Your name, for instance.’

I said, ‘Dr Matthews called me by the name of Grant.’

Susskind said carefully, ‘To the best of our knowledge that is your name. More fully, it is Robert Boyd Grant. Want to know anything else?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘What was I doing? What was my job?’

‘You were a college student studying at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. Remember anything about that?’

I shook my head.

He said suddenly, ‘What’s a mofette?’

‘It’s an opening in the ground from which carbon dioxide is emitted – volcanic in origin.’ I stared at him. ‘How did I know that?’

‘You were majoring in geology,’ he said drily. ‘What was your father’s given name?’

‘I don’t know,’ I said blankly. ‘You said “was”. Is he dead?’

‘Yes,’ said Susskind quickly. ‘Supposing you went to Irving House, New Westminster – what would you expect to find?’

‘A museum.’

‘Have you any brothers or sisters?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Which – if any – political party do you favour?’

I thought about it, then shrugged. ‘I don’t know – but I don’t know if I took any interest in politics at all.’

There were dozens of questions and Susskind shot them at me fast, expecting fast answers. At last he stopped and lit another cigarette. ‘I’ll give it to you straight, Bob, because I don’t believe in hiding unpleasant facts from my customers and because I think you can take it. Your loss of memory is entirely personal, relating solely to yourself. Any knowledge which does not directly impinge on the ego, things like the facts of geology, geographical locations, car driving know-how – all that knowledge has been retained whole and entire.’

He flicked ash carelessly in the direction of the ash-tray. ‘The more personal things concerning yourself and your relationships with others are gone. Not only has your family been blotted out but you can’t remember another single person – not your geology tutor or even your best buddy at college. It’s as though something inside you decided to wipe the slate clean.’

I felt hopelessly lost. What was there left for a man of my age with no personal contacts – no family, no friends? My God, I didn’t even have any enemies, and it’s a poor man who can say that.

Susskind poked me gently with a thick forefinger. ‘Don’t give up now, bud; we haven’t even started. Look at it this way – there’s many a man who would give his soul to be able to start again with a clean slate. Let me explain a few things to you. The unconscious mind is a funny animal with its own operating logic. This logic may appear to be very odd to the conscious mind but it’s still a valid logic working strictly in accordance within certain rules, and what we have to do is to figure out the rules. I’m going to give you some psychological tests and then maybe I’ll know better what makes you tick. I’m also going to do some digging into your background and maybe we can come up with something there.’

I said, ‘Susskind, what chance is there?’

‘I won’t fool you,’ he said. ‘Due to various circumstances which I won’t go into right now, yours is not entirely a straightforward case of loss of memory. Your case is one for the books – and I’ll probably write the book. Look, Bob; a guy gets a knock on the head and he loses his memory – but not for long; within a couple of days, a couple of weeks at the most, he’s normal again. That’s the common course of events. Sometimes it’s worse than that. I’ve just had a case of an old man of eighty who was knocked down in the street. He came round in hospital the next day and found he’d lost a year of his life – he couldn’t remember a damn’ thing of the year previous to the accident and, in my opinion, he never will.’

He waved his cigarette under my nose. ‘That’s general loss of memory. A selective loss of memory like yours isn’t common at all. Sure, it’s happened before and it’ll happen again, but not often. And, like the general loss, recovery is variable. The trouble is that selective loss happens so infrequently that we don’t have much on it. I could give you a line that you’ll have your memory back next week, but I won’t because I don’t know. The only thing we can do is to work on it. Now, my advice to you is to quit worrying about it and to concentrate on other things. As soon as you can use your eyes for reading I’ll bring in some textbooks and you can get back to work. By then the bandages will be off your hands and you can do some writing, too. You have an examination to pass, bud, in twelve months’ time.’

II

Susskind drove me to work and ripped into me when I lagged. His tongue could get a vicious edge to it when he thought it would do me good, and as soon as the bandages were off he pushed my nose down to the textbooks. He gave me a lot of tests – intelligence, personality, vocational – and seemed pleased at the results.

‘You’re no dope,’ he announced, waving a sheaf of papers. ‘You scored a hundred and thirty-three on the Wechsler-Bellevue – you have intelligence, so use it.’

My body was dreadfully scarred, especially on the chest. My hands were unnaturally pink with new skin and when I touched my face I could feel crinkled scar tissue. And that led to something else. One day Matthews came to see me with Susskind in attendance. ‘We’ve got something to talk about, Bob,’ he said.

Susskind chuckled and jerked his head at Matthews. ‘A serious guy, this – very portentous.’

‘It is serious,’ said Matthews. ‘Bob, there’s a decision you have to make. I’ve done all I can do for you in this hospital. Your eyes are as good as new but the rest of you is a bit battered and that’s something I can’t improve on. I’m no genius – I’m just an ordinary hospital surgeon specializing in skin.’ He paused and I could see he was selecting his words. ‘Have you ever wondered why you’ve never seen a mirror?’

I shook my head, and Susskind chipped in, ‘Our Robert Boyd Grant is a very undemanding guy. Would you like to see yourself, Bob?’

I put my fingers to my cheeks and felt the roughness. ‘I don’t know that I would,’ I said, and found myself shaking.

‘You’d better,’ Susskind advised. ‘It’ll be brutal, but it’ll help you make up your mind in the next big decision.’

‘Okay,’ I said.

Susskind snapped his fingers and the nurse left the room to return almost immediately with a large mirror which she laid face down on the table. Then she went out again and closed the door behind her. I looked at the mirror but made no attempt to pick it up. ‘Go ahead,’ said Susskind, so I picked it up reluctantly and turned it over.

‘My God!’ I said, and quickly closed my eyes, feeling the sour taste of vomit in my throat. After a while I looked again. It was a monstrously ugly face, pink and seamed with white lines in arbitrary places. It looked like a child’s first clumsy attempt to depict the human face in wax. There was no character there, no imprint of dawning maturity as there should have been in someone of my age – there was just a blankness.

Matthews said quietly, ‘That’s why you have a private room here.’

I began to laugh. ‘It’s funny; it’s really damn’ funny. Not only have I lost myself, but I’ve lost my face.’

Susskind put his hand on my arm. ‘A face is just a face. No man can choose his own face – it’s something that’s given to him. Just listen to Dr Matthews for a minute.’

Matthews said, ‘I’m no plastic surgeon.’ He gestured at the mirror which I still held. ‘You can see that. You weren’t in any shape for the extensive surgery you needed when you came in here – you’d have died if we had tried to pull any tricks like that. But now you’re in good enough shape for the next step – if you want to take it.’

‘And that is?’

‘More surgery – by a good man in Montreal. The top man in the field in Canada, and maybe in the Western Hemisphere. You can have a face again, and new hands, too.’

‘More surgery!’ I didn’t like that; I’d had enough of it.

‘You have a few days to make up your mind,’ said Matthews.

‘Do you mind, Matt?’ said Susskind. ‘I’ll take over from here.’

‘Of course,’ said Matthews. ‘I’ll leave you to it. I’ll be seeing you, Bob.’

He left the room, closing the door gently. Susskind lit a cigarette and threw the pack on the table. He said quietly, ‘You’d better do it, bud. You can’t walk round with a face like that – not unless you intend taking up a career in the horror movies.’

‘Right!’ I said tightly. I knew it was something that had to be done. I swung on Susskind. ‘Now tell me something – who is paying for all this? Who is paying for this private room? Who is paying for the best plastic surgeon in Canada?’

Susskind clicked his tongue. ‘That’s a mystery. Someone loves you for sure. Every month an envelope comes addressed to Dr Matthews. It contains a thousand dollars in hundred-dollar bills and one of these.’ He fished in his pocket and threw a scrap of paper across the table.

I smoothed it out. There was but one line of typescript on it: FOR THE CARE OF ROBERT BOYD GRANT.

I looked at him suspiciously. ‘You’re not doing this, are you?’

‘Good Christ!’ he said. ‘Show me a hospital headshrinker who can afford to give away twelve thousand bucks a year. I couldn’t afford to give you twelve thousand cents.’ He grinned. ‘But thanks for the compliment.’

I pushed the paper with my finger. ‘Perhaps this is a clue to who I am.’

‘No, it’s not,’ said Susskind flatly. He looked unhappy. ‘Maybe you’ve noticed I’ve not told you much about yourself. I did promise to dig into your background.’

‘I was going to ask you about that.’

‘I did some digging,’ he said. ‘And what I’ve been debating is not what I should tell you, but if I should tell you at all. You know, Bob, people get my profession all wrong. In a case like yours they think I should help you to get back your memory come hell or high water. I take a different view. I’m like the psychiatrist who said that his job was to help men of genius keep their neuroses. I’m not interested in keeping a man normal – I want to keep him happy. It’s a symptom of the sick world we live in that the two terms are not synonymous.’

‘And where do I come in on this?’

He said solemnly, ‘My advice to you is to let it go. Don’t dig into your past. Make a new life for yourself and forget everything that happened before you came here. I’m not going to help you recover your memory.’

I stared at him. ‘Susskind, you can’t say that and expect me just to leave it there.’

‘Won’t you take my word for it?’ he asked gently.

‘No!’ I said. ‘Would you if you were in my place?’

‘I guess not,’ he said, and sighed. ‘I suppose I’ll be bending a few professional ethics, but here goes. I’m going to make it short and sharp. Now, take a hold of yourself, listen to me and shut up until I’ve finished.’

He took a deep breath. ‘Your father deserted your mother soon after you were born, and no one knows if he’s alive or dead. Your mother died when you were ten and, from what I can gather, she was no great loss. She was, to put it frankly, nothing but a cheap chippy and, incidentally, she wasn’t married to your father. That left you an orphan and you went into an institution. It seems you were a young hellion and quite uncontrollable so you soon achieved the official status of delinquent. Had enough?’

‘Go on,’ I whispered.

‘You started your police record by the theft of a car, so you wound up in reform school for that episode. It seems it wasn’t a good reform school; all you learned there was how to make crime pay. You ran away and for six months you existed by petty crime until you were caught. Fortunately you weren’t sent back to the same reform school and you found a warden who knew how to handle you and you began to straighten out. On leaving reform school you were put in a hostel under the care of a probation officer and you did pretty well at high school. Your good intelligence earned you good marks so you went to college. Right then it looked as though you were all right.’

Susskind’s voice took on a savage edge. ‘But you slipped. You couldn’t seem to do anything the straight way. The cops pulled you in for smoking marijuana – another bad mark on the police blotter. Then there was an episode when a girl died in the hands of a quack abortionist – a name was named but nothing could be proved, so maybe we ought to leave that one off the tab. Want any more?’