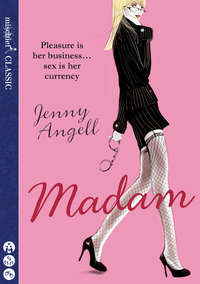

Madam

It sounded pretty good to me. Work and a place to stay, just when I needed both. I said yes. I didn’t consider what people would think when they learned I was working for an escort service, even in the minor role of receptionist. I didn’t consider much of anything. This is probably typical of many of the women who work in the profession: it seems like an answer to a prayer, a way to make ends meet, a way to make a living, for heaven’s sake. And when the reactions trickle in, we’re always surprised by them.

I didn’t think about people’s reactions. I just went to work for Laura.

My first impression was how clean it was: everything was impeccable. Laura ran an escort service that was both in-call and out-call: some girls went out to clients’ homes; others saw the guys there, at Laura’s place. It was never called a bordello. In fact, in all my years in the business, I’ve never heard an in-call place called a bordello. We just called it Laura’s. Maybe it’s just a Boston thing.

So I finally had a job. I was the receptionist; I greeted clients and took all the telephone calls. And listened to the bickering.

“The sheets have to be clean,” Laura kept saying to the girls. That was her constant mantra. You wouldn’t think that clean sheets could ever become such an issue. Whose turn it was to change the sheets, who had last used the front room, who had done the laundry yesterday. That was all that the girls talked about: those damned sheets.

The sheets weren’t my department. I got to talk to the guys.

The clients came in all shapes and sizes, both figuratively and literally. Guys who knew exactly what they wanted, and guys who could be talked into seeing the girl who hadn’t had a call for two days. Young guys that you couldn’t figure out, for the life of you, why they couldn’t get a date on their own; and older men who clearly had no other recourse, even in Boston’s comparatively laid-back sexual climate.

I got good at working the phones, and I got good at it fast. You had to – they’d keep you on the line all night, otherwise. “You have a great voice – you sure I can’t see you? What do you look like? What are you wearing right now?” I got good at deflecting them, just the right edge of flirtatiousness in my voice, just the right edge of business. When I didn’t work, and Laura did the phones, the clients complained. “Where’s Abby?”

I was sleeping on a foldout sofa in her finished basement, sharing the room with an old foosball table and some castoff furniture and lamps from the bedrooms upstairs. That was just fine with me. I had a bank account, and every week I had more money to put into it – the eventual deposit on an apartment somewhere closer to the city than Wilmington.

Because, to tell you the truth, when I wasn’t working, I was bored.

Well, that’s not entirely true. I did have a car that ran most of the time, and when it was running there were a lot of things to do. It was summer, so I could go into Boston and sit on the Common or in the Public Gardens; in the fall I could go out to Concord and walk around Walden Pond. I could go to Lansdowne Street in town on my nights off and hang out in the clubs. But all of it, all the time, I did alone.

I really didn’t know very many people. To be honest, on a day-to-day basis, I was fairly lonely. I didn’t have much of a social life. I worked nights, for one thing. And for another … well, all of my friends from college were starting their careers, or had moved away, or gotten married, or something. I felt a little bereft, as if some train had already pulled out of the station and I had just then realized that I was supposed to be on it.

At Laura’s, though, I wasn’t bored. Here, things were always hopping. Guys stopping in, talking and laughing with me in the living room while they were passing the time before their “date” was free, the girls sitting around waiting to be chosen. It was a cattle call, and as a good feminist I wasn’t altogether comfortable with it. But it was money, extraordinarily good money. And it was more than that – okay, I’ll admit it: it really was exciting. As if I were on the cutting edge of something slightly risqué, slightly dangerous, slightly naughty. As, of course, I was.

I guess the best thing to compare that feeling to is going out at night to the bars, the clubs. How you dance around when you’re getting ready to go out. How you have that little edge of excitement when you first get there, not knowing exactly what you’ll find, who you’ll meet. The tension. And then, when you do strike up a conversation, the flirting, the games, the playfulness and mystery, and the newness of it all. And if it goes well, holding the guy in your power, deciding whether you’re going to sleep with him or not, deciding how far you’re going to let him go, deciding if you’re going to be nice to him or cut him down. All that power, and instead of getting dressed up and going looking for it, it came to me. And I got paid for it. It was my job to be hip and seductive – and unattainable.

“Hello?”

“Yeah, um, I wanted to, um –”

“Make an appointment?” Sweet and seductive.

“Um, yeah.”

“When did you want to come by, sir?” Can’t start by asking for a name – it spooked them. He would say tonight.

“Tonight? Now?”

“That’s fine. I just need to get a little information, sir.” Pretty voice now, nonthreatening. “I need your name and phone number, and I’ll call you right back.”

“Why?”

“It’s for everyone’s protection, sir. Then I can give you directions.”

He relaxed. There was something about that promise that always did it. “Okay. Ed Lawrence. 5551324.”

“I’ll call you right back, Ed.”

After that, it was easy. Directions. Sometimes they’d want to keep me on the phone, run down what they called the “menu,” but I learned how to handle that gracefully as well. “I’m sure that one of the young ladies will suit you, sir.” They always did; the guy just wanted the thrill of prolonging the phone call. His goal was for it to last; mine was to close the deal and move on. Usually I won.

One night Laura had a late arrival. I was asleep downstairs, and she thought – well, I don’t honestly know what she was thinking. Maybe none of the girls were around. Maybe she figured that he was easy and I wouldn’t mind. Whatever was going through her little brain, she sent him down to me.

Big mistake.

First of all, I had never planned on a career in prostitution from anything other than an administrative point of view. Second of all, I was asleep. Third of all, the guy liked to give oral sex, which is why I think she sent him downstairs to me: the scenario would be, he’d go down, I’d never even have to completely wake up, he’d go back upstairs, pay, and leave. What neither Laura nor her client had counted on was the yeast infection I was treating at the time. Her little client went down, all right – and I woke up to this face looming above me, literally foaming at the mouth.

I don’t know which one of us was more freaked out.

And so my career as a call girl ended as soon as it had – albeit involuntarily – begun. But I learned a lot that year I spent doing the phones and working the desk for Laura. I learned about the specifics of running a business like hers, about what worked and what didn’t. I learned about clients and employees and the world’s perception of what we did. I learned a lot about power – about my power.

And most importantly, I learned that I could do it better than her.

So I took my almost-working car and my revived bank account, rented an apartment in Boston’s trendy Bay Village, and opened up my own business. That was nineteen years ago. I’ve been doing it ever since.

* * * * * *

I chose the name Peach from a short story.

It’s as good a source as any for finding a name, I suppose. But it also is weird, in a Twilight Zone kind of way, because the person who wrote that story later came to work for me for a couple of years. What are the chances of that happening? They must be a million to one.

What I didn’t want, above all, was to use my own name. I didn’t want the guys asking for Abby, or knowing anything about Abby. From the very beginning, I wanted an element of deniability to it all. I wanted to both be and not be this new persona.

So I became Peach.

I knew I had to keep my working life and my personal life very, very separate. To my friends and family, I would be Abby. To my girls and my clients, I’d be Peach. And that’s worked pretty well for me.

Which is not to say that I latched onto it right away. If I can sit here and talk calmly about having a family, having a business, juggling them the way any working mother does, you need to know that it didn’t come to me naturally.

In fact, for a whole lot of years, I was much more Peach than I was Abby. Sometimes I think I got a little lost in being Peach … so that’s part of what this story is about. Getting lost.

And getting found.

LOSSES

The door opened slowly, too slowly. The faces were grave.

I was pressed up against the wall in the corridor, scarcely daring to breathe. There was a very expensive vase on the table next to me, from some Chinese dynasty that’s remembered in the Western world only for its porcelain. I had been told to never touch the vase.

The voices inside the room had gone on for far too long, a steady murmur, the murmur of death.

Now the door was opening, and they were all coming out. My mother, her face red and blotchy from crying. Dr. Copeland. Two of my father’s business associates.

Dr. Copeland saw me first and, ignoring the other people – which was very unlike a grown-up – came over and squatted in the hallway next to me. “Abby,” he said, gently, “how long have you been here?”

I stifled a sob. “Forever,” I said. I felt that if I said anything more than that, I’d start crying, and it had been made clear to me that I was not to cry.

He didn’t go away, as I expected him to. He put a hand on my shoulder, instead. “You’re going to need to be a brave girl, Abby.”

“Yes, sir, I know.”

He frowned, as though that was the wrong answer. “But you can be brave and feel sad at the same time,” he said.

I glanced at my mother. She was standing with the light from the window behind her, and all I could see was her thin elegant outline. Her arms were crossed.

I didn’t have to see her face; I already knew what the expression was.

I looked back into the doctor’s kindly eyes with a quick indrawn breath and a little bit of panic. “I’ll be brave,” I assured him. Maybe if I said what he wanted me to say, he’d go away and not say things that made me want to cry.

He didn’t go away.

Instead, he scrunched down and sat on the floor next to me. I clearly heard my mother’s disapproving intake of breath, and stiffened, but she didn’t say anything. “Abby,” said Dr. Copeland, “you know that your daddy is very sick.”

No one had ever called him Daddy before, except me. My mother always prefaced references to him with “Your father.” I nodded.

He nodded, too, as though we had just shared a very deep secret. “Abby, I’m afraid that he’s going to die.”

My heart thudded, and I thought suddenly that I might throw up. I shouldn’t, I knew that I shouldn’t, but I wondered how I could keep it from happening. What can you do? Swallow it all back? I didn’t say anything and swallowed hard, and the feeling receded. Dr. Copeland squeezed my shoulders. “We’re all going to miss your daddy,” he said, “but do you know what, Abby? I think that you’re going to miss him most of all.”

I didn’t know how to respond, so I didn’t say anything.

The doctor gave me one last firm pat on the back and stood up, with some difficulty. One of my father’s business associates gave him a hand. My mother never moved.

Their voices faded away down the hallway and the big sweeping staircase that led downstairs. I stayed where I was, looking longingly at the closed door.

“Abby!” my mother called, her voice sharp. “Come downstairs now!”

I suppose that I went. I was good that way. Obedient.

I never saw my daddy again.

LEAVING MOTHER SUPERIOR

When I left Laura’s place, I had only the faintest idea how to make things work.

What I mean is, I knew what I didn’t want. In retrospect, maybe that’s a pretty good place to start.

I didn’t want to run an in-call service. That was the first decision. For a whole lot of reasons, I didn’t want in-call.

First of all, there was the risk associated with it. There’s always more risk when you have an actual physical place where something illegal is going on. But there was the intrusion, as well, the sense of never quite knowing where work ends and Real Life begins. Laura’s house was – well, Laura’s house. For Laura, my one and only role model in the business, there had never been a clear line between the two. If I didn’t make a distinction, it’s because she never did: her work was her life. I wanted my own space. I wanted my own life.

You have to understand something about this woman: this is someone who made arrangements for her son to get laid when he was fifteen. She sent one of her girls to him in his own bedroom, which was, incidentally, just up the stairs from where the girls all worked. Now that’s one hell of a birthday present from your mother.

I remember one Christmas party – Laura always threw these incredibly extravagant parties – watching her son dancing with the girls with a champagne glass in his hand and an erection in his pants. The girls took off more and more of their clothes as the evening wore on, and Chris was there, right in the middle of it all. He was loving it, of course, but I couldn’t help thinking that his time would have been better spent making out in the back seat of a car somewhere.

There was something about the way Laura dealt with Chris that seemed wrong, really wrong, to me. I realize that many people – maybe even most people – think that sex workers have no ethics, no morals, no code of conduct. Well, I do. I may differ with other people on the definition of that code, but I have one all the same.

Not that I ever had much in common with Laura: we’re both madams; and that is pretty much where the resemblance ends.

She was prissy about cleanliness, as I mentioned, to the point of covering all her furniture in plastic, just like they used to do in the 1950s. (“Well,” she said to me once, as though it were the most logical thing in the world, “you never know who’s going to sit there, or what they’re going to do.” Yuck. I don’t ever want to not know what people are doing on my living room sofa). And yet this prissy housekeeper regularly freebased, leaving all sorts of paraphernalia around in her kitchen – aluminum foil, cigarette ashes, little gram bags of coke.

She was organized beyond belief, keeping this small notebook, adding up, who owed what to whom every night. Yet she couldn’t be bothered with all the work that went into brewing coffee and always drank hers instant.

Laura was, suffice it to say, a study in contrasts.

This showed up in the way she worked, too. She was extremely stupendously generous to her girls, giving them gifts at unexpected moments, singling one or another out and taking her on a surprise shopping spree. Once, she took eight of the girls on a trip to Alaska all expenses paid. It was work, of course, a road show of sorts, but they made absolutely fantastic money and got to travel on top of it.

But she demanded – required – fanatical loyalty. You didn’t work for anybody else while you were working for Laura. Period. She’d cut you off; there were no second chances. And she would invariably find out, because everybody knows everybody else in Boston. A client would usually tip her off – most of the clients were hooked into more than one service. If they called another agency and got someone they’d already met through Laura, they told her. And that was that.

It was as if Laura had this little circle of nuns around her, going off to do their assigned tasks (in this case, fucking men for money) and then returning docilely to the convent under their madam mother superior’s sphere of influence. She didn’t like any of them – including me – having friendships outside of the house. She sure as hell didn’t like any of us having boyfriends outside of the house.

These rules, such as they were, were never articulated, but we all understood them, and we all used them against each other.

I’ve never ever seen such a bunch of gossips as I saw in that house – and where I come from, gossiping is an art form. These girls were impressive. Well, it was only natural that we would gossip: there we all were, stuck in this nouveau-riche house in the back of beyond in suburbia, hanging out together all day with very little to do. No wonder all we talked about was laundry and each other. We probably sounded like junior high kids whispering and giggling by their lockers in a school corridor.

I take that back. We were worse than junior high kids. At least they have the excuse of age, inexperience, and innocence. None of us had any of that going for us.

We were all in our twenties, everyone (except me) dressed in lingerie of some kind, made up, nails lacquered, sitting around on the plastic-covered furniture, waiting. We’d keep the soaps on all day, until a client pulled up outside; then the TV had to be turned off. Major rule, that.

A guy would come in, and everyone would suddenly try to look like it’s a normal thing, all these girls sitting around in their lace and satin and high heels, each one of them competing with the next for his attention.

If that doesn’t make you want to do drugs, I don’t know what would.

If the guy had an appointment with someone, then that was different. Everyone would smile sweetly and the girl would take him off to one of the bedrooms. We’d switch the television back on as soon as we heard the door shut. These were the days before the Internet: we couldn’t just look up what we’d missed on the soaps, so clients were a major interruption.

When we weren’t watching TV, we were talking about anything and everything, but mostly about each other – and Laura. Lord, we gossiped about Laura, and we were vicious – who she was seeing (Laura was always seeing someone), how much coke she’d done the night before, and what she’d said somebody had said about somebody else. I remember, years later, seeing a high school rendition of The Music Man, and being absolutely amazed at how well Rogers and Hammerstein had described our activity.

Of course, the first thing that everyone wanted to do was find Laura and report back to her on who had said what.

In some ways, I guess, I do see some of Laura in myself. We can both be incredibly generous and incredibly selfish. We both have a lot of issues that we deal with by not dealing with them. We both talk – a lot, probably too much. We both manage to survive.

But her style never was my style, and when I left her house and got myself my dream apartment in Boston’s Bay Village, I knew that I had learned enough to know what I didn’t want.

That was a damned good start.

* * * * * *

At that time, the Boston Phoenix had a pullout adult section called “After Dark.” It still has this section, actually, but these days it’s been renamed and redesigned, which I find unfortunate. I’d always liked that name, thought it was pretty classy. Sort of belied the interior. There wasn’t much that you couldn’t find there.

I had a friend once, Claudia, who moved up to the Boston area from New York or New Jersey, someplace where they must be more sophisticated than she – apparently – was. It was late at night. She was tired, overshot the city, and ended up going north on Route 1. Exhausted, she saw a motel, pulled over and went to check in, figuring that she’d find her way to wherever it was that she was supposed to be going in the morning. The name of the motel was the Sir John. (Okay, I know, I know, so she was really tired.) The manager was a little surprised that she wanted the room for the whole night, but I guess he figured, what the hell. She didn’t notice that the motel was right next door to the Golden Banana, one of the North Shore’s biggest and most famous strip clubs. She sure as hell didn’t get much sleep that night.

Anyway, Claudia told me once – years later – that while she was sleepily driving back south on Route 1 into the city the next morning, she was looking around her, and figured that there wasn’t anything that anybody could possibly want in terms of commodities that they couldn’t buy on Route One.

That was how I felt about the After Dark supplement in the Phoenix. There wasn’t anything that you could possibly want that you couldn’t find there.

I thought that After Dark was as wicked as it got.

* * * * * *

My innocence was in part the product of my personality and in part the product of my past. I really do believe at some level that people are fundamentally good and that, given the opportunity, they do the right thing. My observation of and occasional participation in thoughts and actions that are less than pure haven’t completely tarnished this fundamental belief.

My experience – well, that’s something else altogether. If I went by my experience, I’d probably be as cynical as they come.

I grew up in the South, where ladies are ladies, “sir” and “ma’am” are common, and when people ask you how you are, they wait for an answer. That’s a far cry from the brisk how-ya-doin’? of the Northeast. I really do believe that there’s a little of Scarlett O’Hara in every white woman who grew up in the South, a fundamental belief that good manners can get you through just about any situation. For a very long time, I expected people to behave well – just because they should.

That was not exactly the best upbringing for my line of work, but I’ve also found that it tempers the cynicism that is part and parcel of my profession and makes me – or so I’m told – reasonably pleasant to work with. Perhaps not the most overwhelming of compliments, but there are days when I’m willing to settle for reasonably pleasant.

It also means that I smile and acknowledge toll collectors as people, am overwhelmingly polite to telephone operators, and am, of course, kind to dogs and small children. Or is that children and small dogs? I never seem to get that one quite right.

In any case, what the South did give me, besides that take on life and an accent I still cannot entirely get rid of, was a wealth of literature. I love to read; I read everything that is ever been set in front of me, from cereal boxes to VCR instructions, but the voices of the South are what echo the loudest in my world, then and now.

Though proper Southern ladies might blanch at the thought of running an escort service, I haven’t really gone overboard after all. For many of these writers are the same ladies who embrace sexuality with gusto and imagination, who write obsessively and far into the night of breaking free from the oppression of white society (and, some of them, of male society), who tell of awakening to a world where they can be managers of their own destinies. I think that, in the end, some of them might even have applauded me.

It was perhaps under their guidance that I made the final decision about my new business – choosing a niche, an area of specialization, if you will. And when I chose it I was completely aware of the ladies’ voices telling me that it was the right thing to do.

I decided to focus on guys who wanted more than just sex. I know that may sound odd, coming from a madam; but while sex is the blanket under which we sleep, so to speak, it’s not all about sex. Far from it.

It’s about power, and it’s about loneliness, and it’s about a media that constantly tells people that they can Have It All, then springs Real Life on them like some cruel joke. Sex is the battlefield. Sex is the forum where all this stuff gets negotiated, worked out, and practiced. We make so much of sex because we make it mean far more than it was ever supposed to mean. It is only we Americans, with that puritanical past that we can’t seem to rid ourselves of, who see sex in terms of its excesses: as everything or as nothing.