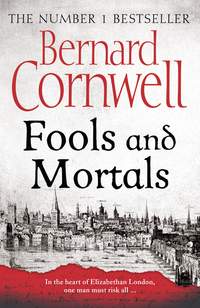

Fools and Mortals

James Burbage chuckled. I ignored him.

Elizabeth Carey clapped her gloved hands when the dance finished. My brother was speaking with her grandmother, who laughed at something he said. I stared at the maid. ‘So you like her,’ James Burbage said caustically. He thought I was staring at Elizabeth Carey.

‘Don’t you?’

‘She’s a rare little kickshaw,’ he allowed, ‘but take your bloody eyes off her. She’ll be married in a couple of months. Married to a Berkeley,’ he went on, ‘Thomas. He gets ploughing rights, not you.’

‘What is she doing here?’ I asked.

‘How the hell would I know?’

‘Maybe she wants to see the play my brother’s written,’ I suggested.

‘He won’t show it to her.’

‘Have you seen it?’

He nodded. ‘But why are you interested? I thought you were leaving us.’

‘I was hoping there’s a part for me,’ I said weakly.

James Burbage laughed. ‘There’s a part for bloody everyone! It’s a big play. It has to be big because we need to do something special for his lordship. Big and new. You don’t serve up cold meat for the Lord Chamberlain’s granddaughter, you give her something fresh. Something frothy.’

‘Frothy?’

‘It’s a wedding, not a bloody funeral. They want singing, dancing, and lovers soaked in moonbeams.’

I looked across the yard. My brother was gesticulating, almost as though he were making a speech from the stage. Lady Anne Hunsdon and her granddaughter were laughing, and the young maid was still staring wide-eyed around the Theatre.

‘Of course,’ Burbage went on, ‘if we perform a play for her wedding then we’ll need to rehearse where we’ll play it.’

‘Somerset House?’ I asked. I knew that was where Lord Hunsdon lived.

‘Bloody roof of the great hall fell in,’ Burbage said, sounding amused, ‘so like as not we’ll be rehearsing in their Blackfriars house.’

‘Where I’ll play a woman,’ I said bitterly.

He turned and frowned at me. ‘Is that it? You’re tired of wearing a skirt?’

‘I’m too old! My voice has broken.’

Burbage waved to show me the whole circle of the playhouse. ‘Look at it, boy! Timber, plaster and lath. Rain-rotted planks on the forestage, some slaps of paint, and that’s all it is. But we turn it into ancient Rome, into Persia, into Ephesus, and the groundlings believe it. They stare. They gasp! You know what your brother told me?’ He had gripped my jerkin and pulled me close. ‘They don’t see what they see, they see what they think they see.’ He let go of me and gave a crooked grin. ‘He says things like that, your brother, but I know what he means. When you act, they think they see a woman! Maybe you can’t play a young girl any more, but as a woman in her prime, you’re good!’

‘I’ve a man’s voice,’ I said sullenly.

‘Aye, and you shave, and you have a cock, but when you speak small they love it!’

‘But for how long?’ I demanded. ‘In a month or so you’ll say I’m only good for men’s parts, and you’ve plenty of men players.’

‘You want to play the hero?’ he sneered.

I said nothing to that. His son Richard, who I had seen crossing swords with Henry Condell, always played the hero in our plays, and there was a temptation to think that he was only given the best parts because his father owned the playhouse’s lease, just as it was tempting to believe he had been made one of the company’s Sharers because of his father, but in truth he was good. People loved him. They walked across Finsbury Fields to watch Richard Burbage win the girl, destroy the villains, and put the world to rights. Richard was only three or four years older than I, which meant I had no chance of winning a girl or of dazzling an audience with my swordplay. And some of the apprentices, the boys who were capering onstage right now, were growing taller and could soon play the parts I played, and that would save the playhouse money because apprentices were paid in pennies. At least I got a couple of shillings a week, but for how long?

The sun was glinting off the puddles among the yard’s cobblestones. Elizabeth Carey and her grandmother, holding their skirts up, crossed to the stage, and the boys there stopped dancing, took off their caps, and bowed, all except Simon, who offered an elaborate curtsey instead. Lady Anne spoke to them, and they laughed, then she turned, and, with her granddaughter beside her, headed for the Theatre’s entrance. Elizabeth was talking animatedly. I saw that the hair had been plucked from her forehead, raising her hairline by a fashionable inch or more. ‘Fairies,’ I heard her say, ‘I do adore fairies!’

James Burbage and I, anticipating that the ladies would walk within a few paces of the gallery where we talked, had taken off our caps, which meant my long hair fell about my face. I brushed it back. ‘We shall have to ask our chaplain to exorcise the house,’ Elizabeth Carey went on happily, ‘in case the fairies stay!’

‘Better a flock of fairies than the rats in Blackfriars,’ Lady Anne said shortly, then caught sight of me and stopped. ‘You were good last night,’ she said abruptly.

‘My lady,’ I said, bowing.

‘I like a good death.’

‘It was thrilling,’ Elizabeth Carey added. Her face, already merry, brightened. ‘When you died,’ she said, letting go of her skirts and clasping her hands in front of her breasts, ‘I didn’t expect that, and I was so …’ she hesitated, not finding the word she wanted for a heartbeat, ‘mortified.’

‘Thank you, my lady,’ I said dutifully.

‘And now it’s so strange seeing you in a doublet!’ she exclaimed.

‘To the carriage, my dear,’ her grandmother interrupted.

‘You must play the Queen of the Fairies,’ Elizabeth Carey ordered me with mock severity.

The young maid’s eyes widened. She was staring at me, and I stared back. She had grey eyes. I thought I saw a hint of a smile again, a suspicion of mischief in her face. Was she mocking me because I would play a woman? Then, realising that I might offend Elizabeth Carey by ignoring her, I bowed a second time. ‘Your ladyship,’ I said, for lack of anything else to say.

‘Come, Elizabeth,’ Lady Anne ordered. ‘And you, Silvia,’ she added sharply to the grey-eyed maid, who was still looking at me.

Silvia! I thought it the most beautiful name I had ever heard.

James Burbage was laughing. When the women and their guards had left, he pulled his cap onto his cropped grey hair. ‘Mortified,’ he said. ‘Mortified! The mort has wit.’

‘We’re doing a play about fairies?’ I asked in disgust.

‘Fairies and fools,’ he said, ‘and it’s not fully finished yet.’ He paused, scratching his short beard. ‘But mayhap you’re right, Richard.’

‘Right?’

‘Mayhap it’s time we gave you men’s parts. You’re tall! That doesn’t signify for parts like Uashti, because she’s a queen. But tall is better for men’s parts.’ He frowned towards the stage. ‘Simon’s not really tall enough, is he? Scarcely comes up to a dwarf’s arsehole. And your voice will deepen more as you add years, and you do act well.’ He climbed the gallery to the outer corridor. ‘You act well, so if we give you a man’s part in the wedding play, will you stay through the winter?’

I hesitated, then remembered that James Burbage was a man of his word. A hard man, my brother said, but a fair one. ‘Is that a promise, Mister Burbage?’ I asked.

‘As near as I can make it a promise, yes it is.’ He spat on his hand and held it out to me. ‘I’ll do the best I can to make sure you play a man in the wedding play. That’s my promise.’

I shook his hand. ‘Thank you,’ I said.

‘But right now you’re the Queen of bloody Persia, so get up onstage and be queenly.’

I got up onstage and was queenly.

TWO

SATURDAY.

The weather had cleared to leave a pale sky in which the early winter sun cast long shadows even at noon, when the bells of the city churches rang in jangling disharmony. High clouds blew ragged from the west, but there was no hint of rain, and the fine weather meant that we could perform, and so, when the cacophony of the noon bells ended, our trumpeter, standing on the Theatre’s tower, sounded a flourish, and the flag, which displayed the red cross of Saint George, was hoisted to show we were presenting a play.

The first playgoers began arriving before one o’clock. They came across Finsbury Fields, a trickle at first, but the trickle swelled, as men, women, apprentices, tradesmen, and gentry, all came from the Cripplegate. Others walked up from the Bishopsgate and turned down the narrow path that led by the horse pond to the playhouse, where one-eyed Jeremiah stood at the entrance with a locked box that had a slit in its lid, and where two men, both armed with swords, cudgels, and scowls, guarded the old soldier and his box. Every playgoer had to drop a penny through the slot. Three whores from the Dolphin tavern were selling hazelnuts just outside the Theatre, Blind Michael, who was guarded by a huge deaf and dumb son, was selling oysters, and Pitchfork Harry sold bottles of ale. The crowd, as always, was in a merry mood. They greeted old friends, chatted, and laughed as the yard filled.

Richer folk went to the smaller door, paid tuppence, and climbed the stairs to the galleries, where, for yet another penny, they could hire a cushion to soften the oak benches. Women leaned over the upper balustrade to stare at the groundlings, and some young men, often elegantly dressed, gazed back. Many of the men who had paid their penny to stand in the yard had no intention of staying there. Instead they scanned the galleries for the prettiest women, and, seeing one they liked, paid more pennies to climb the stairs.

Will Kemp peered through a spyhole. ‘A goodly number,’ he said.

‘How many?’ someone asked.

‘Fifteen hundred?’ he guessed. ‘And they’re still coming. I’m surprised.’

‘Surprised?’ John Heminges queried. ‘Why?’

‘Because this play is a piece of shit, that’s why.’ Will stepped away from the spyhole and picked up a pair of boots. ‘Still,’ he went on, ‘I like being in plays that are shit.’

‘Good Lord, you do? Why?’

‘Because then I don’t have to watch the damn things.’

‘Jean,’ someone called from the shadows, ‘this hose is torn.’

‘I’ll bring you another.’

The trumpeter sounded his flourish more often, each cascade of notes being greeted by a cheer from the gathering crowd. ‘Remind me what jig we’re doing today?’ Henry Condell asked.

‘Jeremiah,’ Will Kemp answered.

‘Again?’

‘They like it,’ Will said aggressively.

George Bryan was shivering in a corner of the room. Not shivering with cold, but nervousness. One leg twitched uncontrollably. He was blinking, biting his lip, trying to say his lines in a low voice, but stuttering instead. George was always terrified before a play, though once on the stage he appeared the soul of confidence. Richard Burbage was stretching in another corner, loosening his arms and legs for the acrobatics to come, while Simon Willoughby, resplendent in an ivory-panelled skirt and with his hair piled high and hung with glass rubies, swirled back and forth in the tiring room’s centre until Alan Rust growled at him to be still, whereupon Simon sulkily retreated to the back of the room, sat on a barrel, and picked his nose. My brother came down the stairs, evidently from the office where the money boxes were taken to be emptied. ‘Seven lordlings on the stage,’ he said happily. It cost sixpence to sit at the stage’s edge, so the Sharers had just earned three shillings and sixpence from seven hard stools. I was lucky to earn three shillings and sixpence in a week, and soon, when the winter weather closed the playhouse down for days at a time, I would be lucky to earn a shilling.

Jean, our seamstress, shaved me. It was my second shave that day, and this one, with cold water, stung as she scraped my chin, upper lip, cheeks, and then my hairline to heighten my forehead. She used tweezers to shape my eyebrows, then told me to tip my head back. ‘I hate this,’ I said.

‘Don’t be a fusspot, Richard!’ She dipped a sliver of wood into a small pot. ‘And don’t blink!’ She held the sliver over my right eye. A drop of liquid fell into my eye, and I blinked. It stung. ‘Now the other one,’ she said.

‘They call it deadly nightshade,’ I said.

‘You’re being silly. It’s just juice of belladonna.’ She shook a second drop into my left eye. ‘There. All done.’ The belladonna, besides stinging and making my vision blurry for a time, dilated my pupils so that my eyes seemed larger. I kept them closed as Jean covered my face, neck, and upper chest with ceruse, the paste that made my skin look white as snow. ‘Now the black,’ she said happily, and used a finger to smear a paste of pig’s fat and soot around my eyes. ‘You look lovely!’

I growled, and she laughed. She took another pot from her capacious bag and leaned close. ‘Cochineal, darling, don’t tell Simon.’

‘Why not?’

‘I gave him madder because it’s cheaper,’ she whispered, then smeared my lips with her finger, leaving them red as cherries. I was no longer Richard, I was Uashti, Queen of Persia.

‘Give us a kiss!’ Henry Condell called to me.

‘Dear sweet God,’ George Bryan muttered, and bent his head between his knees. I thought he was going to vomit, but he sat up and took a deep breath. ‘Dear sweet God,’ he said again. We all ignored him, we had seen and heard it before, and knew he would play as well as ever. My brother held a breastplate to his chest and let Richard Burbage buckle the straps.

‘There should be a helmet too,’ my brother said, shrugging to make the newly buckled breastplate comfortable. ‘Where’s the helmet?’

‘In the fur chest,’ Jean called, ‘by the back door.’

‘What’s it doing there?’

‘Keeping warm.’

I climbed the wooden stairs to the upper room where most of the costumes and the smaller pieces of stage furniture were stored, and where the musicians were tuning their instruments. ‘You look lovely, Richard,’ Philip, who was the chief musician, greeted me.

‘Put your lute up your arse,’ I told him, ‘and give it a twist.’ We were friends.

‘Give us a kiss first.’

‘Then give it another twist,’ I finished. I peered through the balcony door. The musicians would play on the balcony that afternoon, and a tabour player was already standing there. ‘Nice big audience,’ he told me, then tapped his drumsticks on the tabour’s skin, provoking a cheer from the crowd below.

I turned back into the room and climbed the ladder to the tower roof. I was clumsy in my long dark skirts, but I hoisted them up and slowly mounted the rungs. ‘I can see your arse!’ Philip called.

‘You lucky musician,’ I said, then clambered through the trapdoor onto the platform, where Will Tawyer the trumpeter stood.

Will grinned at me. ‘I was waiting for you,’ he said. Will knew I would join him, because climbing to the rickety platform before a performance was my superstition. Every time I played in the Theatre I had to climb the tower. There was no reason I knew of, except a firm belief that I would play badly if I did not struggle up the ladder in my heavy and cumbersome skirts. All the players had their superstitions. John Heminges wore a hare’s foot on a silver chain, George Bryan, in between his shivering and twitching, would reach up to touch a beam in the tiring room ceiling, Will Kemp would force a kiss on Jean, the seamstress, while Richard Burbage would draw his sword and kiss the blade. My brother tried to pretend he had no ritual, but when he thought no one was looking, he made the sign of the cross. He was no papist, but when he was challenged by Will Kemp, who accused him of kissing the filthy arse of the Great Whore of Babylon, my brother had just laughed. ‘I do it,’ he explained, ‘because it was the very first thing I ever did on a stage. At least, the very first thing that I was paid to do on a stage.’

‘And what part was that?’

‘Cardinal Pandulph.’

‘You were in that piece of crap?’

My brother nodded. ‘First play I ever performed. At least as a paid player. The Troublesome Reign of King John, and Cardinal Pandulph was forever crossing himself. It signifies nothing.’

‘It signifies Rome!’

‘And does your kissing Jean signify love for her?’

‘God forbid!’

‘You could do worse,’ my brother had said, ‘she works hard.’

‘Too hard!’ Jean had overheard the conversation. ‘I need someone to help me. One woman can’t do everything.’

‘She can try,’ Will Kemp growled.

‘Bleeding animal,’ Jean said under her breath.

The superstitions, whether it was climbing the tower, making the sign of the cross, or kissing the seamstress, were hardly meaningless, because we all believed that they kept the devils away from the playhouse; the devils that made us forget our words or brought us a sullen audience or made the trapdoor in the stage stick, which it sometimes did after damp weather.

I stood for a moment longer on the tower’s platform. A breeze gusted, fretting the red-crossed flag on its pole above us. I looked south and saw there was no flag and no trumpeter on the Curtain playhouse, which meant they were not even presenting a beast show on this fine afternoon. Beyond the empty playhouse, the city was dark beneath its ever-present smoke. I flinched as Will Tawyer blew another fanfare to rouse the groundlings, who dutifully cheered the sound. ‘That woke them up,’ Will said happily.

‘It woke me up too,’ I said. I stared north, past the tower of Saint Leonard’s church, to the green hills beyond the village of Shoreditch where cloud shadows raced across woods and hedges. The noise of the audience rose from the yard and galleries. The playhouse was almost full, which meant the Sharers would have six or seven pounds in coins this day, and I would be paid a shilling.

I clambered down the ladder. ‘Do you have a ritual?’ I asked Phil.

‘A ritual?’

‘Something you must do before every performance?’

‘I look up your skirts!’

‘Besides that.’

He grinned. ‘I kiss Robert’s crumhorn.’

‘Really?’

Robert, Phil’s friend, raised the instrument, which looked like a shepherd’s short crook. ‘He kisses it,’ he said, ‘and I blow it.’

The other musicians laughed. I laughed too, then went down the stairs and saw Isaiah Humble, the bookkeeper, pinning a paper by the right-hand stage door. ‘Your entrances and exits, masters,’ he called, as he always did. We all knew our entrances, but it was comforting to know the list was there. It was even more comforting to see Pickles, the playhouse’s bad-tempered cat, waiting by the same door. Everyone using that door had to touch Pickles to keep the demons at bay and if Pickles lashed out with a spiteful claw and drew blood, that was regarded as an especially good omen.

‘I need a piss,’ Thomas Pope said. He always needed a piss before a play.

‘Piss in your breeches,’ Will Kemp growled, as he also always did.

‘Jean! Where’s the green cloak?’ John Duke called.

‘Where it always is.’

‘Sweet Jesus,’ George Bryan said. He was visibly shaking, but no one tried to calm or encourage him because that would bring ill-luck, and besides, we all knew that George’s whimpering nerves would vanish the moment he went through one of the stage doors, and the mouse turned into a lion.

The white-faced, red-lipped, black-eyed boys in their pretty dresses gathered by the left-hand door, their tresses bulked out with hair-rolls and ribbons. Simon Willoughby stared into a polished piece of metal nailed by that door and admired his reflection. Then Will the trumpeter, far above us, blew six high and urgent notes that sounded like a call on the hunting field. The first city church had just struck two o’clock.

‘Wait,’ my brother said, as he always did, and we stood silent as one after another the churches rang the hour, filling the sky with their bells. The last bell tolled, but no one moved and no one spoke. Even the waiting crowd was silent. Then, somewhere to the south of the city, a distant church sounded the hours. It tolled a good minute after all the others, but still we did not move.

‘We still wait,’ my brother said quietly. He had his eyes closed.

‘Dear God,’ George Bryan whispered.

‘I really do need a piss!’ Thomas Pope moaned.

‘Keep the words moving!’ Will Kemp snarled, as he always did. ‘Keep them moving!’

And then, after what seemed an eternity, Saint Leonard’s rang two o’clock. The church, just to the north of us in Shoreditch, was always the last, and the crowd, knowing that its bells were the signal for the play to begin, cheered again. Footsteps sounded above us as the musicians went onto the balcony. There was a pause, then the trumpet flourished a final time, and the two drums began beating.

‘Now!’ my brother said to the waiting boys, and Simon Willoughby threw open the left-hand door and the boys danced onto the stage.

We were players and we were playing.

‘The fretting heads of furious foes have skill,’ I said, ‘as well by fraud as force to find their prey!’ I spoke small, meaning I pitched my voice as high as I could and still kept it loud enough to reach the folk leaning over the upper gallery’s balustrade. ‘In smiling looks doth lurk a lot as ill,’ I piped, ‘as where both stern and sturdy streams do sway!’

In fairness I have to say my brother had not written this hodge-pudding of nonsense, though God knows he has written enough idiocies that I have declaimed onstage. We were playing Hester and Ahasuerus, so I was Uashti, Queen of Persia, though I was dressed in fine modern clothes, the only concession to the biblical setting being a great cloak of fur-trimmed linen that swirled prettily whenever I turned around. The cloak was a very dark grey, almost black, because I was a villainess, the heroine being the nose-picker Simon Willoughby, the plump little sixteen-year-old, who played Hester in a pale cream cloak. God only knows why the role was named Hester, because her name was Esther, but whatever she was called, she was about to become Queen of Persia in my place. The story is from the Bible, so I have no need to retell it here except to explain where the play has changed the tale. In our version, Uashti tries to poison Hester, fails, has a skin-the-cat moment of fury, then relinquishes her crown and licks Hester’s plump arse, which is what I was now doing. I was kneeling to the smirking little bastard. ‘Be still, good Queen,’ I said, and gave the word ‘still’ a lot more force than it needed because Willoughby, the preening little slut, was flicking a fan of peacock feathers to keep the audience’s eyes on his over-painted face, ‘their refuge and their rock,’ I went on, ‘as they are thine to serve in love and fear. So fraud nor force nor foreign foe may stand against the strength of thy most puissant hand!’

The groundlings love this stuff. Some cheered as I prostrated myself in front of Hester, while the richer folk in the galleries clapped their hands. They knew they were not really watching a tale from the Bible. Uashti might be Queen of Persia, but she represented Katherine of Aragon, while Hester was Queen Anne Boleyn, and the whole piece was an arse-sucking flattery of Elizabeth, which pretended that the popish Katherine had respected the rightful status of Elizabeth’s Protestant mother. We did the play rarely because, even though audiences seemed to like the tale, it truly was dross, but when the dross is written by a royal chaplain it has to be performed now and then. That chaplain, the Most Reverend William Venables, was in the lower gallery, beaming at us, convinced he had written a masterpiece. He thought we were performing the play because of its brilliance, but in truth we were currying royal favour because the city’s aldermen were having another of their attempts to close the playhouses. The Theatre was built outside the city’s boundaries, so they had no authority over us, but they did possess influence. They said we were sinks of sin, and cockpits of corruption, ‘which is wholly accurate, of course,’ my brother liked to say.