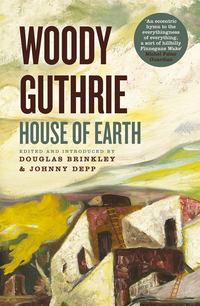

House of Earth

Guthrie’s letter to Eddie Albert—previously unpublished, like House of Earth itself—is a recent discovery. It illuminates how mesmerized Guthrie was by the vision of his own adobe home while trying to survive the brutal winter of 1937.

We sent off to Washington DC and get us back a book about sun dried brick.

Them guys up there around that Dept of Agriculture knows a right smart. They can write about work and make you think you got a job.

They wrote that Adobe Brick book so dadgum interesting that you got to slack up every couple of pages to pull the mud and hay out from between your toes.

People around here for some reason aint got much faith in a adobe mud house. Old Timers dont seem to think it would stand up. But this here Dept of Agr. Book has got a map there in it which shows what parts of the country the dirt will work and tells in no hidden words that sun dried brick is the answer to many a dustblown familys prayer.

Since by a lot of hard work, which us dustbowlers are long on, and a very small cash cost, any family can raise a dern good house which is bug proof, fireproof, and cool in summer, and not windy inside in the winter.

I have been sort of experimenting out here in the yard with mud bricks, and after you make a bunch of em, you’d say yourself if a fellow caint raise up a house out of dust and water, by George, he caint raise it up out of nothing.

Right on hand I got a good cement man when he can get work and also a uncle of mine thats lived up here on the plains for 45 years, and he knows all of these hills and hollers and breaks in the land and canyons, and river bottoms where we can get stuff to built with, like timber and rock and sand, and he’s too old to get a job but just the right age to build.

This cement workers is just right freshly married. But could work some.

Now since this climate is fairly dry and mighty dusty, and in view of the wind that blows, and the wheat that somehow grows, why hadn’t these good cheap houses be introduced around here, which by the bricks in my back yard, I think is a big success.

If folks caint find no work at nothing else they can build em a house. There is plenty of exercise to it.

We’ve owned this little wood house for six years and it has been a blessing over and over, and the same amount of work and money spent on this house will raise one just exactly twice this good from the very well advertised dust of the earth.

It would be nearly dustproof, and a whole lot warmer, and last longer to boot. But folks around here just havent studied it out, or got no information from the government, or somehow are walking around over and overlooking their own salvation.

Local lumber yards dont advertize mud and straw because you cant find a spot on earth without it, but you see old adobe brick houses almost everywhere that are as old as Hitlers tricks, and still standing, like the Jews.

If I was aiming to preach you a sermon on the subject I would get a good lungful of air and say that man is himself a adobe house, some sort of a streamlined old temple.

But what I want to come around to before the paper runs out is this: We’re scratching our heads about where to raise this $300 and we would furnish the labor and work, and we would write up a note of some kind a telling that this house belonged to somebody else till we could pay it out. . . .

Course the payments would have to run pretty low till we could get strung out and the weather thaw out and the sun take a notion to come out, but it would be a loan and as welcome as a gift.

In this case, a few retakes on the lenders part could shore change a mighty bleak picture into a good one, and maybe an endless One.

Starting in the late 1930s, Guthrie toyed with the idea of writing a panegyric to survivors of the Dust Bowl with adobe as the leitmotif. Because John Steinbeck had stolen his thunder by writing The Grapes of Wrath, about the Okie migration westward from Oklahoma and Texas to California, Guthrie decided to focus instead on his own authentic experience as a survivor of Black Sunday and the great mud blizzard. Also, to his ears, the dialect of Steinbeck’s uprooted Joads fell short of realism. To Guthrie, true-to-life bad grammar was the essential way to capture the spirit of how people really talked on the frontier. Like Joel Chandler Harris, the author of the Uncle Remus tales, he was an excellent listener. So House of Earth, in Guthrie’s mind, would be less an adulterated documentation of the meteorological calamities than a pioneering work in capturing Texas-Okie dialects. Steinbeck, like all reporters, focused on the dust cyclones, but Guthrie knew that the frigid winter storms in West Texas during the Dust Bowl era also crippled his fellow plainsmen. Guthrie granted Steinbeck the diploma for documenting the diaspora to California. Nevertheless, he himself claimed for literature those brave and stubborn souls who decided to stay put in the Texas Panhandle. It was one thing for Steinbeck, in The Grapes of Wrath, to feature families who were searching for a land of milk and honey, but Guthrie’s own heart was with those stubborn dirt farmers who remained behind in the Great Plains to stand up to the bankers, lumber barons, and agribusinesses that had desecrated beautiful wild Texas with overgrazing, clear-cutting, strip-mining, and reckless farming practices. The gouged land and the working folks got diddly-squat … nothing … zero … nada … zilch. (For a while Guthrie used the nom de plume Alonzo Zilch.)

While Guthrie’s twenty-five-year-old heart stayed in Texas, his legs would soon be bound for California. Much like Tike Hamlin, the main character in House of Earth, Guthrie paced the floorboards of his hovel at 408 South Russell Street in Pampa during the great mud blizzard of 1937, wondering how to find meaning in the drought-stricken misery of the Depression. His salvation required a choice: to go to California or to build an adobe homestead in Texas. When the character Ella May Hamlin screams, “Why has there got to be always something to knock you down? Why is this country full of things you can’t see, things that beat you down, kick you down, throw you around, and kill out your hope?” the reader feels that Guthrie is expressing his own deep-seated frustration. He decided he would have to try his luck in California if he wanted a steady income. Having learned the Carter Family’s old-style country tunes, and with original songs like “Ramblin’ Round” and “Blowing Down This Old Dusty Road” in his repertoire, he was determined to become a folksinger who mattered. In early 1937—the exact week is unknown, but it was after the snow had thawed—Guthrie packed up his painting supplies, put new strings on his guitar, and bummed a ride in a beer delivery truck to Groom, Texas. Hopping out of the cab and waving good-bye, he started hitching down Highway 66 (what Steinbeck called the “road of flight”), where migrants were begging for food in every flyspeck town, to Los Angeles.

There is an almost biblical sense of trials and tribulations in the obstacles Guthrie would confront in California. Like all the other migrants on Highway 66, he always felt starvation banging on his rib cage. From time to time, he pawned his guitar to buy food. Like the photographer Dorothea Lange, he visited farm camps in California’s San Joaquin Valley, stunned to see so many children suffering from malnutrition. But then Guthrie’s big break came when he landed a job as an entertainer on KFVD radio in Los Angeles, singing “old-time” traditional songs with his partner Maxine Crissman (“Lefty Lou from Mizzou”). His hillbilly demeanor was affecting, and the local airwaves allowed Guthrie to reach fellow workers in migrant camps with his nostalgic songs about life in Oklahoma and Texas. For a while, he broadcast out of the XELO studio from Villa Acuña in the Mexican state of Coahuila; the station’s powerful signal went all over the American Midwest and Canada, unimpeded by topography and unfettered by FCC regulations.

Many radio station owners wanted Guthrie to be a smooth cowboy swing crooner like Bob Wills (“My Adobe Hacienda”) and Gene Autry (“Back in the Saddle Again”). Guthrie, however, had developed a different strategy for folksinging that he clung to uncompromisingly. “I hate a song that makes you think you’re not any good,” he explained. “I hate a song that makes you think that you are just born to lose. Bound to lose. No good to nobody. No good for nothing. Because you are either too old or too young or too fat or too slim or too ugly or too this or too that … songs that run you down or songs that poke fun of you on account of your bad luck or your hard traveling. I am out to fight those kinds of songs to my very last breath of air and my last drop of blood.”

When Guthrie became a “hobo reporter” for The Light in 1938, he traveled extensively, reporting on the 1.25 million displaced Americans of the late 1930s. The squalor of the migrant camps angered him. He kept wishing the poor could live in adobe homes. “People living hungrier than rats and dirtier than dogs,” Guthrie wrote, “in the land of sun and a valley of night.” Guthrie came to understand that, contrary to myth, these so-called Dust Bowl refugees hadn’t been chased out of Texas by dusters; nor had they been made obsolete by large farm tractors. They were victims of banks and landlords who had evicted them simply for reasons of greed. These money-grubbers wanted to evict tenant farmers in order to turn a patchwork quilt of little farms into huge cattle conglomerates, and they thereby forced rural folks into poverty. During his travels around California, Guthrie saw migrants living in cardboard boxes, mildewed tents, filthy huts, and orange-crate shanties. Every flimsy structure known to mankind had been built, but adobe homes were nowhere to be found. This rankled Guthrie boundlessly. What would Jesus Christ think of these predatory money changers destroying the family farms of America and forcing good folks to live in wretched lean-tos? “For every farmer who was dusted out or tractored out,” Guthrie said, “another ten were chased out by bankers.”

The Franklin Roosevelt administration tried to help poor farmers through the federal Resettlement Administration (the successor to the Farm Security Administration, famous for collaborating with such artists as Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Pare Lorentz) by issuing grants of ten to forty-five dollars a month to the down-and-out; farmers would line up at the Resettlement Administration offices for these grants. President Roosevelt also aimed to help farmers like the Hamlins by ordering the US Forest Service to plant millions of acres of trees and shrubs on farms to serve as shelterbelts (and reduce wind erosion) and by having the Department of Agriculture start digging lakes in Oklahoma and Texas to provide irrigation for the dry iron grass. These noble New Deal efforts helped but didn’t completely solve the crisis.

3

The legend of Guthrie as a folksinger is etched in the collective consciousness of America. Compositions like “Deportee,” “Pastures of Plenty,” and “Pretty Boy Floyd” became national treasures, like Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack and Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. With the slogan “This Machine Kills Fascists” emblazoned on his guitar, Guthrie tramped around the country, a self-styled cowboy-hobo and jack-of-all-trades championing the underdog in his proletarian lyrics. When Guthrie heard Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” sung by Kate Smith ad nauseam in 1939, on radio stations from coast to coast, he decided to strike out against the lyrical rot and false comfort of the patriotic song. Holed up in Hanover House—a low-rent hotel on the corner of Forty-Third Street and Sixth Avenue—Guthrie wrote a rebuttal to “God Bless America” on February 23, 1940. He originally titled the song “God Blessed America” but eventually settled on “This Land Is Your Land.” Because Guthrie saved thousands of his song lyrics in first and final drafts, we’re lucky to still have the fourth and sixth verses of the ballad, pertaining to class inequality:

As I went walking, I saw a sign there,

And on the sign there, it said “no trespassing.” *

But on the other side, it didn’t say nothing,

That side was made for you and me.

In the squares of the city, in the shadow of a steeple;

By the relief office, I’d seen my people.

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking,

Is this land made for you and me?

Guthrie signed the lyric sheet, “All you can write is what you see, Woody G., N.Y., N.Y., N.Y.” (During that week in Hanover House, the hyperproductive Guthrie also wrote “The Government Road,” “Dirty Overhalls,” “Will Rogers Highway,” and “Hangknot Slipknot.”)

Over the decades, “This Land Is Your Land” has become more a populist manifesto than a popular song. It’s Guthrie’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’,” a call to arms. There is a hymnlike simplicity to Woody’s signature tune. The lyric is clear and focused. Woody’s art always reflected his political leanings, but that was all part of his esprit. He wasn’t, in the end, a persona. What you heard was real as rain. There was no separation between song and singer.

Everything about a Guthrie song accentuated the positive in people struggling against all odds. He would trumpet hope at every turn. He even once referred to himself as a “hoping machine,” in a letter when he was courting a future wife. Guthrie sought to empower those who had nothing, to uplift those who had lost everything in the Great Depression, and to comfort those who found themselves repeatedly at the mercy of Mother Nature. He could not help raging at the swinish injustice of it all, in the two fierce verses in “This Land Is Your Land” that slammed private property and food shortages—verses that were lost during the period of McCarthy’s “red scare.” A relatively unknown, but very important, verse—“Nobody living can ever stop me … Nobody living can ever make me turn back”—challenges the agents of the authoritarian state who prevent free access to the land that was “made for you and me.” Reading all the verses now, one is impressed by Guthrie’s ability to elucidate such simple, brutal truths in such resolute words.

In many ways, House of Earth—originally handwritten in a steno notebook and then typed by Guthrie himself—is a companion piece to “This Land Is Your Land.” It’s another not-so-subtle paean to the plight of Everyman. After all, in a socialist utopia, once a Great Plains family acquired land, it would need to build a sturdy domicile on the property. The novel is therefore pitched somewhere between rural realism and proletarian protest, with a static narrative but a lovely portrait of the Panhandle and the marginalized people who made a life there in the 1930s. It’s Guthrie addressing the elemental question of how a sharecropper couple, field hands, could best live in a Dust Bowl–prone West Texas. Trapped in adverse economic conditions, unable to pay their bills or earn anything more than a subsistence wage, Guthrie’s main characters dream of a better way. Tike Hamlin—like Guthrie himself—wants to build an adobe home for his family. Wherever Guthrie went, no matter the day or time, he talked about someday having his own adobe home. “I am stubborn as the devil, want to built it my own self,” Guthrie wrote to a friend in 1947, “with my own hands and my own labors out of pisse de terra sod, soil, and rock and clay.”

Before writing House of Earth, he had composed his autobiography, Bound for Glory, in the early 1940s. In that work, Guthrie proved to be a genius at capturing the rural Texas-Oklahoma dialect in realistic prose. Somehow he managed to straddle the line between “outsider” folk art and “insider” high art. Bound for Glory— which was made into a motion picture in 1976—is an impressive first try from an amateur inspired by native radicalism. Guthrie’s great accomplishment was that his sui generis singing voice, his trademark, prospered in his prose.

Another book of Guthrie’s, Seeds of Man—about a silver mine around Big Bend National Park in Texas—was largely a memoir, though fictionalized in parts. There is an authenticity about this book that was—and still is—ennobling. He saw his next prose project—House of Earth—as a heartfelt paean to rural poverty. (Just a month after Guthrie had written “This Land Is Your Land,” he played the guitar and regaled his audience with stories about hard times in the Dust Bowl at a now legendary benefit for migrant workers hosted by the John Steinbeck Committee to Aid Agricultural Organization.)

What Guthrie wanted to explore in House of Earth was how places like Pampa could be something more than tumbleweed ghost towns, how sharecropping families could put down permanent roots in West Texas. He wanted to tackle such topics as overgrazing and the ecological threats inherent in fragmenting native habitats. He elucidated the need for class warfare in rural Texas, for a pitchfork rebellion of the 99 percent working folks against the 1 percent financiers. His outlook was socialistic. (Bricks to all landlords! Bankruptcy to all timber dealers! Curses on real estate maggots glutting themselves on the poor!) And he unapologetically announces that being a farmer is God’s highest calling.

One of the main attractions of Guthrie’s writing—and of House of Earth in particular—is our awareness that the author has personally experienced the privations he describes. Yet this is different from pure autobiography. Guthrie gets to the essence of poor folks without looking down on them from a higher perch like James Agee or Jacob Riis. His gritty realism is communal, expressing oneness with the subjects. The Hamlins, it seems, have more in common with the pioneers of the Oregon Trail than with a modern-day couple sleeping on rollout beds in Amarillo during the Internet age. Objects such as cowbells, oil stoves, flickering lamps, and orange-crate shelves speak of a bygone era when electricity hadn’t yet made it to rural America. But while the atmosphere of House of Earth places the novel firmly in the Great Depression, the themes that Guthrie ponders—misery, worry, tears, fun, and lonesomeness—are as old as human history. Guthrie’s aim is to remind readers that they are merely specks of dust in the long march forward from the days of the cavemen.

The Hamlins have a hard life in a flimsy wooden shack, yet exist with extreme (and emotionally fraught) vitality. The reader learns at the outset that their home is not up to the function of keeping out the elements. So Tike starts exasperatedly espousing the idealistic gospel of adobe. On the farm, life persists, and the reader is treated to an extended, earthy lovemaking scene. This intimate description serves a purpose: Guthrie elevates the biological act to a representation of Tike and Ella May’s oneness with the land, the farm, and each other. And yet, the land is not the Hamlins’ to do with as they please—and so the building of their adobe house remains painfully out of reach. The narrative then concerns itself with domestic interactions between Tike and Ella May. Despite their great energy and playfulness, dissatisfaction wells up in them. In the closing scenes, in which Ella May gives birth, we learn more about their financial woes and how tenant farmers lived on tenterhooks during the Great Depression when they had no property rights.

4

When the folklorist Alan Lomax read the first chapter of House of Earth (“Dry Rosin”), he was bowled over, amazed at how Guthrie expressed the emotions of the downtrodden with such realism and dignity. For months Lomax encouraged Guthrie to finish the book, saying that he’d “considered dropping everything I was doing” just to sell the novel. “It was quite simply,” Lomax wrote, “the best material I’d ever seen written about that section of the country.” House of Earth demonstrates that Guthrie’s social conscience is comparable to Steinbeck’s and that Guthrie, like D. H. Lawrence in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was willing to explore raw sexuality.

Guthrie apparently never showed Lomax the other three chapters of the novel: “Termites,” “Auction Block,” and “Hammer Ring.” His hopes for House of Earth lay in Hollywood. He mailed the finished manuscript to the filmmaker Irving Lerner, who had worked on such socially conscious documentaries as One Third of a Nation (1939), Valley Town (1940), and The Land (1941). Guthrie hoped that Lerner would make the novel into a low-budget feature film. This never came to pass. The book languished in obscurity. Only quite recently, when the University of Tulsa started assembling a Woody Guthrie collection, did House of Earth reemerge into the light. The Lerner estate had found the treasure when organizing its own archives in Los Angeles. The manuscript and a cache of letters written by Guthrie and Lerner to each other were promptly shipped to Tulsa’s McFarlin Library for permanent housing. Coincidentally, while hunting down information about Bob Dylan for a Rolling Stone project, we stumbled on the novel. Like Lomax, we grew determined to have House of Earth published properly by a New York house, as Guthrie surely would have wanted.

The question has been asked: Why wasn’t House of Earth published in the late 1940s? Why would Guthrie work so furiously on a novel and then let it die on the vine? There are a few possible answers. Most probably, he was hoping a movie deal might emerge; that took patience. Perhaps Guthrie sensed that some of the content was passé (the fertility cycle trope, for example, was frowned on by critics) or that the sexually provocative language was ahead of its time (graphic sex of the “stiff penis” variety was not yet acceptable in literature during the 1940s). The lovemaking between Tike and Ella May is a brave bit of emotive writing and an able exploration of the psychological dynamics of intercourse. But it’s a scene that, in the age when Tropic of Cancer was banned, would have been misconstrued as pornographic. Another impediment to publication may have been Guthrie’s employment of hillbilly dialect. This perhaps made it difficult for New York literary circles to embrace House of Earth as high art in the 1940s, though the dialect comes across as noble in our own period of linguistic archaeology. Also, left-leaning originality was hard to mass-market in the Truman era, when Soviet communism was public enemy number one. And critics at the time were bound to dismiss the novel’s enthusiasm for southwestern adobe as fetishistic.

Toward the end of House of Earth, Tike rails against the sheeplike mentality of honest folks in Texas and Oklahoma who let low-down capitalist vultures steal from them. Long before Willie Nelson and Neil Young championed “Farm Aid,” a movement of the 1980s to stop industrial agriculture from running amok on rural families, Guthrie worried about middle-class folks who were being robbed by greedy banks. As Tike prepares to make love to Ella May in the barn scene in House of Earth, his head swirls with thoughts of how everything around him—“house, barn, the iron water tank, the windmill, little henhouse, the old Ryckzyck shack, the whole farm, the whole ranch”—was “a part of him, the same as an egg from the farm went into his mouth and down his throat and was a part of him.” Tike is biologically one with even the hay on his leased property.

In 1947, after years of gestation, House of Earth was finished. Shortly thereafter Guthrie’s health started to deteriorate from complications of Huntington’s disease. While disciples like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Pete Seeger popularized his folk repertoire, House of Earth remained among Lerner’s papers. Like a mural by Thomas Hart Benton or a novel by Erskine Caldwell, it was an artifact from a different era: it didn’t fit into any of the standard categories of popular fiction during the Cold War. But, as Guthrie might say, “All good things in due time.” The unerring rightness of southwestern adobe living is now more apparent than ever. Oscar Wilde was right: “Literature always anticipates life.” It’s almost as if Guthrie had written House of Earth prophetically, with global warming in mind.