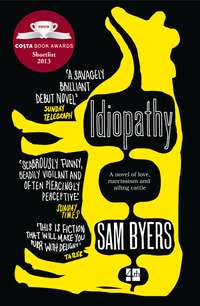

Idiopathy

He adjusted his body clock to optimise his respite. He had, on several carefully spaced evenings, gone to bed before Angelica and then feigned sleep when she followed him. He liked to vary the presentation. One night he was simply asleep, another he gave the appearance of having drifted off with a book on his chest. He’d pictured, as he carefully positioned himself on his back with the book spread over his chest, Angelica smiling to herself as she reached out and removed the book and then turned out the light before sliding into the bed beside him. In reality, though, she had simply ignored him, and Daniel had found himself trapped beneath the book, unsure if he should pretend to wake and make himself more comfortable or simply maintain the lie and remain as he was. He’d chosen the latter, spending half the night pinned and tense and unable either to sleep or to roll over.

He had, for a time, experimented with rising early and doing his dreaming while awake, staring out at the suburban dawn with its little tiles of domestic light, watching the gathering mosaic of parted curtains and illuminated rooms as the street followed him into the day. But Angelica, alert to his movements even through her ear plugs and eye-mask, had attuned herself to his sleep cycles and begun following him downstairs after mere minutes of blissful solitude, sitting beside him as he sipped his coffee and strained for small talk. She strained with him, of course, or even for him at times. Tell me something, she’d say, folding her legs beneath her on the sofa and tucking her dressing gown over her feet. What are you thinking? He didn’t know, couldn’t say. She had a way of reaching out and gently tapping his temple – What’s going on in there? The more she pursued, the more he fled. Morning after grey morning, they sat side by side in resigned silence, each frowning slightly, shaping words they never said, until eventually she smiled and sighed and said, Isn’t it great that we can just sit together quietly like this?

So he left for work early, arriving at The Centre long before he needed to be there. He liked to walk the labs before the nine o’clock influx, pacing the brushed-glass workstations and aluminium fittings; listening to the way the instruments hummed and ticked in isolation. When there was no one else there, you could feel the laboratories breathe. He never touched anything. Much like the rest of Daniel’s life, you could have dusted for his prints and found barely a whorled smudge. He simply liked the feel of the place, the energy. Four wide rooms of quiet research and gently scrolling diagnostics, lit with the faintest tint of green. At the back was a heated bio-dome that housed a perfectly engineered cornfield. He liked to make his way through the clinical hush and then stand at the edge of the field, squinting until the clear walls and ceilings dimmed from his peripheral vision and there was nothing left but the gold expanse of the crop. In the winter, it was especially comforting, and he enjoyed the oddness of stripping off his overcoat and standing for a moment in the middle of a perfectly false summer’s day, the smell of the field wafting up at him like the very essence of summers gone by, sheltered from the rain as it lashed the arched glass roof and made a marbled, swimming mess of the sky.

Daniel was conjoined with Angelica the way two melting candles might form a single, shapeless mass of wax. She believed in a degree of closeness and intimacy that was almost mystical. She wanted them to overlap, to meld. The difficulty was that Daniel had done too good a job of painting himself in her colours. Ventriloquism had always been a knack of his. On a good day, he could even do the faces to match. He found the easiest disguise was blandness – the disguise of having no face at all. Angelica didn’t know, or could briefly sense but then optimistically disregard, the discreet territories of himself he kept in reserve. He told her he loved her. He did love her. She loved him. It was awful. Love, with all its formless cushioning and puffed-up protection, had inflated between them like an air bag in a car crash. She looked into his eyes while they made love and he imagined himself in a narrow tunnel with the weight of a river rushing above him. He would never leave her. He lived in fear of her leaving him.

Angelica was a year younger than Daniel, and several years behind in terms of her professional development, largely because she had invested large acreages of her life into what she thought of as her personal development. She’d travelled. She’d explored. She’d spent time in a number of places yet appeared, when it came down to it, to have been nowhere. Travellers always talked that way, Daniel noticed. It was designed to give the impression of nomadic flux, of freedom – a concept Angelica and her friends seemed to hold dear. To Daniel, it was an odd sort of liberty, as though their very pursuit of a limitless, weightless existence somehow constrained and burdened them. For him, freedom had always seemed more static, more solidly hewn. It was freedom from fear; the relief of no longer having to search – for a job, a partner, a house. Not for him the Goan sands and full-moon raves and Hare Krishna platitudes. Better the yearly bonus, the sense of completion that accompanied genuine quantifiable achievement. Or so he’d always thought, and tried to think still, now, as he felt himself trapped and terrified of being free.

Daniel had met Angelica, slightly predictably but with an air of what-the-hell, in a bar, on a sleety festive Thursday, at a time when he’d composed in his mind such a long and compelling list of things he didn’t want in a woman that he could be attracted only to their absence. Naturally, Angelica had her good qualities, but it was the things she lacked that drew him to her. She was the anti-Katherine. She wasn’t harsh or abrasive. She didn’t shout, she wasn’t difficult to be around and, critically, Daniel could not imagine her defecating. After Katherine, who had a sort of rolling-news approach to the workings of her body; who detailed her bowel movements over breakfast; who followed him into the bathroom while he was brushing his teeth and studied her sanitary pad like it was the morning headlines, Daniel had forsworn the vulgar physicality of women he slept with, and so gauged each woman he met against the ease with which he could imagine her shitting or menstruating. Throughout his first conversation with Angelica, then, as they stood uncomfortably close in the press of damp bar-hoppers and shouted into each other’s ears over the clatter, Daniel had tried and happily failed to demolish her beauty in his mind. His attraction to her was complex; reverse-reactive. It wasn’t that he fancied her, it was that he couldn’t imagine himself not fancying her.

Their conversation had flowed with their drinks: pleasantries over cut-price pints; intimacies over marked-up cocktails, and again Angelica had revealed herself to be everything Katherine was not in that she not only had a sense of the wider world but actually at times expressed opinions on how it could be improved. One of Katherine’s most frequent complaints about Daniel was that he was little more than an idealistic middle-class liberal with a conveniently vague grasp of reality. Part of what made Daniel so angry about this remark was that it was true, and like any liberal he wanted less to change the world than simply to be around people who wanted the world to be different in all the same ways. What a thrill, then, to hear Angelica voicing her opinions on global responsibility, rising sea levels, and whatever was going on with the cattle. It wasn’t that it was love, it was simply that it was closer to Daniel’s idea of love than anything that had come along before.

They’d spent their dating days doing good. It was a bad time for beef, even then. Up and down the country, cattle were trancing out. Farmers were finding lone members of the herd at the edges of fields staring blank and unblinking into the middle distance, starving and dehydrating to death. Experts were at a loss. The term Bovine Idiopathic Entrancement, far from a diagnosis, was coined as an admission of ignorance. Daniel and Angelica had hounded McDonald’s. On two occasions they’d taken to the streets, handing out poorly printed leaflets that spoke of the evil behind convenience. They felt they were kicking the Golden Arches while they were down. At some point, the environment had become the new Third World. Convenience was out. You had to work for your food. Anything fast was suspicious. Ease was both corrupted and corrupting.

Awful, then, that they, as a couple, were so convenient, so easy. People bought McDonald’s because they knew what they were getting. Daniel stayed with Angelica for much the same reason. She was as she’d been advertised. She did what it said on her wrapper.

For Angelica, her daily life and sense of global concern were inextricably linked. There was always room for improvement, for growth. She regarded herself (and, unfortunately, Daniel and their relationship) as something to be worked on, a project with no definable goal or conclusion. That’s something I’ve been doing a lot of work on recently, she’d say. I know I need to work on that. She read deeply and voraciously on the subject of her own shortcomings. She didn’t talk, she expressed. She didn’t think, she explored. Indeed, she appeared to have reached the conclusion that thinking itself was chancy, and possibly a symptom of some deep-seated syndrome or flaw or maladjustment that needed to be explored.

‘Do I think too much?’ she’d ask, midway through some minor domestic task. ‘Like, I feel like I’m thinking all the time, and sometimes that’s really good? But other times it’s really bad. Like it’s really paralysing, just thinking about stuff all the time.’

Daniel wasn’t sure it was possible to think too much. He often found his private thoughts considerably more interesting than day-to-day events, to the point where he sometimes resented day-to-day events for interfering with his thoughts, an issue which Angelica had raised on more than one occasion, and on which he’d begrudgingly agreed he might need to work.

‘I need to be more spontaneous,’ she’d say. ‘We both do. Let’s be really spontaneous this weekend. Let’s agree we’re going to do something totally unplanned and nuts.’

She’d said this twice. The first time they’d spent much of Saturday debating activities that might be suitably nuts, and then deciding all of them were rather predictable, at which point they’d gone shopping. The second time they’d agreed not to debate anything and each ended up making completely separate and un-discussed plans, over which they then argued for the rest of the weekend.

Their sex life was, naturally, the most symptomatic area of all. It was constantly in a state of redress. Like some grossly over-ambitious architectural project, it always seemed to be propped up with scaffolding and obstinately deviating from plans. Intimacy was an issue. Intimacy and spontaneity and the balance of the two. Sometimes, for example, Angelica got it into her head that she wanted to tantrically merge for hours on end, seeking some semi-mystical state of union she’d read about in a second-hand book. At other times, she felt the whole dimming-the-lights-and-dousing-the-room-with-incense planning of the thing made it all rather moribund and predictable, at which point she just wanted to screw and be done with it. The difficulty was that Daniel never knew, so to speak, if he was coming or going, meaning he tended to get the timing wrong and find himself accused of having either intimacy issues or some sort of problem with spontaneity and passion. As far as his personal preferences went, suffice to say his heart pretty much sank whenever he saw Angelica fumbling for a joss stick.

High-minded though they were, frugality seemed always to escape them. The things they owned seemed to breed. Domesticity, it transpired, came down to a collection of products and a desire to continually augment those products until everything was just so, which of course it never could be, because what, then, would there be to work on? Objects broke, ran out, needed cleaning (which necessitated the use of further, more specialised products). Lacking children as they did, Daniel and Angelica needed something to tend to or they risked falling into the kind of vapid complacency they both professed to fear but also secretly craved. The rough, cluttered, faintly shabby look perfected by several of their friends wasn’t an option. They needed all the same stuff as normal people. Multi-surface sprays that fizzed on contact; moisturisers that toned and lifted and lightly tanned; shampoos that thickened and added shine. Daniel and Angelica dreamed of a better world but still baulked at the smell of each other’s shit, necessitating a variety of lavender-based infusions and, when merely masking the odour wouldn’t suffice, a reserve artillery of heavy chemistry that promised nothing short of a bacterial Armageddon. They had stuff for everything. There was a sense of carefully applied science. Their juicer was powerful enough to wring nectar from a breeze block; their bedding gave off scents designed to stimulate sleep. Their vitamin regimen was rigorous and complex. Daniel hadn’t smoked in months. Each morning before work, after an invigorating ylang-ylang-infused shower and a breakfast of carefully selected nutritionally balanced cereals, he threw carrots and apples and oddly shaped multi-ethnic fruits he couldn’t name into the gaping maw of his juicer and knocked back 250 ml of pure unadulterated well-being. Like so much in his life, it was healthily vile, but the sourness was sweetened by virtue: you could boast about it; it made you a better person.

All their friends were couples. Angelica had been in a long-term relationship (her phrase) and her ex had treated her so badly that she’d taken all their friends with her when they split. Daniel had few friends of his own. Her friends were their friends now. At weekends they took it in turns to play host. One couple cooked, the other brought wine. A sense of competition lurked amidst the camaraderie. The plurals were barbed. And we just had such a great time in New York, did you guys go anywhere this year? Or even the supposed simplicity of How are you two? Couldn’t one be up and one be down?

The most common visitors were Sebastian and Plum, who were visiting this particular evening. Plum was Plum’s given name. She had those kinds of parents. Her sister was called Nasturtium. Sebastian, rather ironically, was not Sebastian’s given name at all but simply a name he happened to prefer to what he’d actually been christened: Walter. Sebastian, much to his chagrin, had those kinds of parents. He’d been baptised and, for a while, home schooled, but had shaken it all loose at the age of eighteen by running away to Goa, where he’d undergone a tie-dyed transformation and returned as Sebastian Freud. His parents were outraged, but Sebastian was past parents. He was past a lot of things. Like Angelica, he’d worked through a lot of stuff. He was narcissistically altruistic. He bragged about his selflessness. His soliloquies were two parts arrogance to one part suggestive condescension. He thought Daniel was repressed. Daniel thought he was a prick. They’d tolerated each other during the days of doing good, which Daniel now thought of slightly more clear-sightedly as the days of impressing Angelica, but in the six months following Daniel’s acceptance of a position at the Jenssen-Meyer Centre, which Sebastian happened to be targeting with one of his protests, their ability to pretend to get along had, to say the least, waned.

Daniel was, broadly speaking, honest about his work in The Centre’s PR department, and honest about the work in which The Centre was engaged. What he was not quite honest about was how he had got the job and the moral flexibility he was encouraged to enjoy now that he had it.

Operating in the field of biochemical crop research, the Jenssen-Meyer Centre was run by two of the eighties’ more notable radical humanist biologists: Lens Jenssen and Colin Meyer. Their credentials when it came to life in the trenches of the nascent environmental movement were, as Daniel had grown adept at pointing out, pretty unimpeachable. Given their background, and the fact that the aim of their work was the creation of a sustainable food source, Jenssen and Meyer were understandably upset to find themselves the target of exactly the sort of protest they probably would have been part of twenty years ago, and so, when it came to selecting someone to manage their public statements, were keen to select someone who had what they slightly euphemistically called an understanding of the dreadlocked crusties currently frightening investors by touting banners in the car park. Daniel, who by that stage felt he had, if he was honest, done enough not only to impress Angelica but also to slough off the slash-and-burn anti-ideology of Katherine’s world-view, and who was beginning, much as he’d enjoyed what he would later think of as his gap-months, to tire of Angelica’s idealism and to miss the sense of professional advancement that had formed the bedrock of his life to date, saw an opportunity to balance one half of his life against the other, and so was excited to find himself shortlisted, which went some way to explaining the zeal with which he interviewed.

Jenssen and Meyer were seen as elitist, he told them. Their image had become secretive; self-satisfied. Their shared background in radical biochemistry; their once-alternative lifestyle which they’d always worn as a badge of pride, wasn’t actually cause for admiration at all. The hippies, far from seeing Jenssen and Meyer as kindred spirits made good, saw them as sell-outs. To them, all engagement with the powers-that-be was suspicious. Hippies didn’t want to achieve anything, Daniel said. They wanted to sit in rented halls and recapitulate old arguments, all the while comforting themselves with the notion that their inability to change anything was simply because society was tilted against them. This meant that Jenssen and Meyer had, in the eyes of the demonstrators outside their building, committed a kind of double sin. Not only had they sold out, they’d also accidentally demonstrated that selling out worked, and for that, Daniel said, the hippies were never going to forgive them. He understood that it might have been a point of personal pride to win over people they thought should have been their friends in the first place, but the truth was it was time to make new friends. Rather than selling the ideological integrity of their research to the alternative set, he suggested, they needed to sell the respectability of their research to the respectable set, because at the moment they were falling between two ideologically opposed stools and doing a grand job of pleasing neither. Just as the demonstrators used Jenssen and Meyer’s background as proof they had no loyalty to firm ideals, so the more conservative amongst the research communities used it as evidence of their potential flakiness. In the end, no one cared about the hippies and what they thought. If Jenssen and Meyer wanted to succeed, Daniel said, building to a crescendo, it was time for a clean break. Fuck the hippies.

From here, naturally, he pointed to his well-documented background in the corporate sphere as well as his less-documented background in the hippie sphere and suggested that if they found anyone with a more perfect balance of the particular elements that this role would require someone to juggle they should let him know. They offered him the job on the spot. He sold it to Angelica as a way of genuinely making a difference, and to her credit she’d given him the benefit of the doubt. Sebastian, on the other hand, had not only failed to stop demonstrating but, probably out of sheer spite, had stepped up his efforts, meaning that the façade of friendship they maintained for Angelica’s benefit was now thinner than ever. Nonetheless, every weekend Daniel had to smile his way through dinner, the phrase fuck the hippies sticking rather uncomfortably in his throat.

The evenings were all much of a muchness, and Daniel found them tolerable only in that they spared him having to spend another evening bonding with Angelica. Angelica always cooked – something lumpy and hearty and altogether heinous – and Sebastian and Plum always brought wine – something dry and unusual with impeccable political credentials.

Tonight was, naturally, no different. They arrived late enough to demonstrate their casual disregard for bourgeois punctuality yet not so late as to relinquish the right to get angry if anyone was ever overly behind schedule for one of their own gatherings. Plum was wearing a dress she’d fashioned herself from a collection of period cushion covers sourced, as she explained, from an amazing little charity shop they’d found while holidaying in Brighton. Sebastian was wearing brown boots with heels that were borderline Cuban, stonewashed jeans and a jacket with a Nehru collar. His long hair was tied back in a way that made it look like his smile was caused by tension across his scalp and face.

‘Ange,’ said Sebastian, kissing Angelica on the lips (cheek-kissing was repressed, everyone seemed to agree, and reserved only for uncomfortable or false situations). ‘Great to see you. God, you look fabulous. Doesn’t she look fabulous, Daniel?’

‘Of course,’ said Daniel as Plum kissed him on the cheek. ‘As do you, Plum.’

‘Barium irrigation,’ she said, reaching over to embrace Angelica while Sebastian waved awkwardly at Daniel across the hugging women. ‘I feel like superwoman.’

‘It’s amazing how much crap you can hold in your colon,’ said Angelica.

They seated themselves at the dining table, where Angelica had lit candles. The stereo was playing something Brazilian. Angelica went off to gather the meal.

‘Can I do anything, hon?’ called Daniel.

‘No,’ she called back, much to his disappointment. ‘Just stay and entertain, darling.’

Sebastian smiled. ‘You don’t mind me telling Ange how fabulous she looks, do you?’

‘Of course not,’ said Daniel. ‘How are you, anyway?’

‘Wonderful,’ said Plum.

‘Lots happening,’ said Sebastian.

‘That’s great,’ said Daniel.

‘And how about you?’ said Sebastian, flashing his teeth. ‘How’s life in the lab?’

‘I don’t work in the labs,’ Daniel replied, for perhaps the hundredth time.

‘Oh yes, I always forget. You don’t research, you just proselytise the research.’

‘Oh leave him alone, Seb,’ said Plum.

‘I’m just ribbing him a bit. You don’t mind, do you, Dan?’

Daniel did mind, and also disliked having his name abbreviated, but commented on neither transgression, since to do so would ruin the atmosphere. Angelica set great store by atmosphere, and woe betide anyone who was caught jeopardising it.

‘Well I think proselytising’s a bit strong,’ said Daniel. ‘It’s more a sort of educational capacity, really.’

‘You’re the minister of propaganda then,’ said Sebastian.

‘Not really, no.’

Like many in his circle, Sebastian determinedly equated anything he didn’t like with fascism.

‘You’ve seen the headlines, I assume?’ said Sebastian. ‘God, what am I saying? You probably wrote the headlines.’

‘Which headlines are we talking about?’

‘You know, the ones about The Centre.’

‘Oh, those,’ said Daniel. ‘Yes, we’re not sure where those are coming from, actually.’

‘I assume you’re about to tell me they’re untrue.’

‘Well I wasn’t actually, but since you mention it, yes, they’re totally false.’

‘Spoken like a true believer.’

‘Believing’s got nothing to do with it. The Centre is researching a sustainable crop source. Whatever’s going on with the cows is completely unrelated.’

‘But what if they’ve been eating modified crops? What if this is a glimpse of us in the future?’

‘If you think cows eat crops then you’re incredibly naïve. More to the point, if it’s true that this is a virus that’s capable of jumping the species barrier, which everyone seems to think it is, then that would rule out the food source as the infecting agent.’