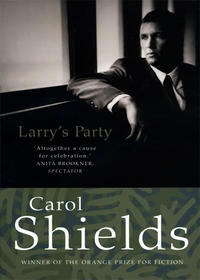

Larry’s Party

Larry’s Party

Carol Shields

Contents

Cover

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE: Fifteen Minutes in the Life of Larry Weller 1977

CHAPTER TWO: Larry’s Love 1978

CHAPTER THREE: Larry’s Folks 1980

CHAPTER FOUR: Larry’s Work 1981

CHAPTER FIVE: Larry’s Words 1983

CHAPTER SIX: Larry’s Friends 1984

CHAPTER SEVEN: Larry’s Penis 1986

CHAPTER EIGHT: Larry Inc. 1988

CHAPTER NINE: Larry So Far 1990

CHAPTER TEN: Larry’s Kid 1991

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Larry’s Search for the Wonderful and the Good 1992

CHAPTER TWELVE: Larry’s Threads 1993–4

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Men Called Larry 1995

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: Larry’s Living Tissues 1996

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: Larry’s Party 1997

Larry’s Party

THE WORK OF CAROL SHIELDS

Carol Shields: The Stone Diaries

Carol Shields: Unless

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

For Joseph, Nicholas, and Sofia

With thanks to a few men who have offered suggestions in the writing of this book: David Arnason, Tommy Banks, Tony Giardini, Jack Hodgins, Robin Hoople, Don Huband, Steve Hunt, Dayv James-French, the late Jim Keller, Joseph Krotz, Jake MacDonald, Brian MacKinnon, Don McCarthy, Bill Neville, Mark Morton, Doug Pepper, Gord Peters, John Ralston Saul, Donald Shields, John Shields, Ray Singer, Harry Strub and Max Wyman.

Thanks, too, to Maggie Dwyer and Jane Gralen and to the staff at the Winnipeg Public Library.

What is this mighty labyrinth – the earth, But a wild maze the moment of our birth?

(“Reflections on Walking in the Maze at Hampton Court” British Magazine, 1747)

CHAPTER ONE Fifteen Minutes in the Life of Larry Weller 1977

By mistake Larry Weller took someone else’s Harris tweed jacket instead of his own, and it wasn’t till he jammed his hand in the pocket that he knew something was wrong.

His hand was traveling straight into a silky void. His five fingers pushed down, looking for the balled-up Kleenex from his own familiar worn-out pocket, the nickels and dimes, the ticket receipts from all the movies he and Dorrie had been seeing lately. Also those hard little bits of lint, like meteor grit, that never seem to lose themselves once they’ve worked into the seams.

This pocket – today’s pocket – was different. Clean, a slippery valley. The stitches he touched at the bottom weren’t his stitches. His fingertips glided now on a sweet little sea of lining. He grabbed for the buttons. Leather, the real thing. And something else – the sleeves were a good half inch longer than they should have been.

This jacket was twice the value of his own. The texture, the seams. You could see it got sent all the time to the cleaners. Another thing, you could tell by the way the shoulders sprang out that this jacket got parked on a thick wooden hanger at night. Above a row of polished shoes. Refilling its tweedy warp and woof with oxygenated air.

He should have run back to the coffee shop to see if his own jacket was still scrunched there on the back of his chair, but it was already quarter to six, and Dorrie was expecting him at six sharp, and it was rush hour and he wasn’t anywhere near the bus stop.

And – the thought came to him – what’s the point? A jacket’s a jacket. A person who patronizes a place like Cafe Capri is almost asking to get his jacket copped. This way all that’s happened is a kind of exchange.

Forget the bus, he decided. He’d walk. He’d stroll. In his hot new Harris tweed apparel. He’d push his shoulders along, letting them roll loose in their sockets. Forward with the right shoulder, bam, then the left shoulder coming up from behind. He’d let his arms swing wide. Fan his fingers out. Here comes the Big Guy, watch out for the Big Guy.

The sleeves rubbed light across the back of his hands, scratchy but not too scratchy.

And then he saw that the cuff buttons were leather too, a smaller-size version of the main buttons, but the same design, a sort of cross-pattern like a pecan pie cut in quarters, only the slices overlapped this little bit. You could feel the raised design with your finger, the way the four quadrants of leather crossed over and over each other, their edges cut wavy on the inside margin. These waves intersected in the middle, dived down there in a dark center and disappeared. A black hole in the button universe. Zero.

Quadrant was a word Larry hadn’t even thought of for about ten years, not since geometry class, grade eleven.

The color of the jacket was mixed shades of brown, a strong background of freckled tobacco tones with subtle orange flecks. Very subtle. No one would say: hey, here comes this person with orange flecks distributed across his jacket. You’d have to be one inch away before you took in those flecks.

Orange wasn’t Larry’s favorite color, at least not in the clothing line. He remembered he’d had orange swim trunks back in high school, MacDonald Secondary, probably about two sizes too big, since he was always worrying at that time in his life about his bulge showing, which was exactly the opposite of most guys, who made a big point of showing what they had. Modesty ran in his family, his mum, his dad, his sister, Midge, and once modesty gets into your veins you’re stuck with it. Dorrie, on the other hand, doesn’t even shut the bathroom door when she’s in there, going. A different kind of family altogether.

He’d had orange socks once too, neon orange. That didn’t last too long. Pretty soon he was back to white socks. Sports socks. You got a choice between a red stripe around the top, a blue stripe, or no stripe at all. Even geeks like Larry and his friend Bill Herschel, who didn’t go in for sports, they still wore those thick cotton sports socks every single day. You bought them three in a pack and they lasted about a week before they fell into holes. You always thought, hey, what a bargain, three pairs of socks at this fantastic price!

White socks went on for a long time in Larry’s life. A whole era.

Usually he didn’t button a jacket, but it just came to him as he was walking along that he wanted to do up one of those leather buttons, the middle one. It felt good, not too tight over the gut. The guy must be about his own size, 40 medium, which is lucky for him. If, for example, he’d picked up Larry’s old jacket, he could throw it in the garbage tomorrow, but at least he wasn’t walking around Winnipeg with just his shirt on his back. The nights got cool this time of year. Rain was forecast too.

A lot of people don’t know that Harris tweed is virtually waterproof. You’d think cloth this thick and woolly would soak up water like a sponge, but, in actual fact, rain slides right off the surface. This was explained to Larry by a knowledgeable old guy who worked in menswear at Hector’s. That would be, what, nine, ten years ago, before Hector’s went out of business. Larry could tell that this wasn’t just a sales pitch. The guy – he wore a lapel button that said “Salesman of the Year” – talked about how the sheep they’ve got over there are covered with special long oily hair that repels water. This made sense to Larry, a sheep standing out in the rain day and night. That was his protection.

Dorrie kept wanting him to buy a khaki trenchcoat, but he doesn’t need one, not with his Harris tweed. You don’t want bulk when you’re walking along. He walks a lot. It’s when he does his thinking. He hums his thoughts out on the air like music; they’ve got a disco beat: My name is Larry Weller. I’m a floral designer, twenty-six years old, and I’m walking down Notre Dame Avenue, in the city of Winnipeg, in the country of Canada, in the month of April, in the year 1977, and I’m thinking hard. About being hungry, about being late, about having sex later on tonight. About how great I feel in this other guy’s Harris tweed jacket.

Cars were zipping along, horns honking, trucks going by every couple of seconds, people yelling at each other. Not a quiet neighborhood. But even with all the noise blaring out, Larry kept hearing this tiny slidey little underneath noise. He’d been hearing it for the last couple of minutes. Whoosh, wash, whoosh, wash. It was coming out of the body of Larry J. Weller. It wasn’t that he found it objectionable. He liked it, as a matter of fact, but he just wanted to know what it was.

He whooshed past the Triple Value Store, past the Portuguese Funeral Home, past Big Mike’s where they had their windows full of ski equipment on sale. The store was packed with people wearing spring clothes, denim jackets, super-flare pants, and so on, but they were already thinking ahead to next winter. They had snow in their heads instead of a nice hot beach. That’s one thing Larry appreciates about Dorrie. She lives in the moment. When it’s snowing she thinks about snow. When it’s spring, like right now, she’s thinking about getting some new sandals. That’s what she’s doing this very minute: buying sandals at Shoes Express, their two-for-one sale. Larry knows she’s probably made up her mind already, but she told him she’d wait till he got to the store before buying. She wants to make sure Larry likes what she decides on, even though sandals are just sandals to him. Just a bunch of straps.

Dorrie knows how to stretch money. She saves the fifty-cents-off coupons from Ponderosa – which’ll give you a rib eye steak, baked potato and salad, all for $1.69. Or she’ll hear a rumor that next week shoe prices are going to get slashed double. So she’ll say to the guy at Shoes Express, “Look, can you hold these for me till next Wednesday or Thursday or whatever, so I can get in on the sale price?”

It comes to Larry, what the noise is. It’s the lining of his jacket moving back and forth across his shoulders as he strolls along, also the lining material sliding up and down against his shirt-sleeves. He can make it softer if he slows down. Or louder if he lifts his arm and waves at that guy across the street that he doesn’t even know. The guy’s waving back, he’s trying to figure out who Larry is – hey, who’s that man striding along over there, that man in the very top-line Harris tweed jacket?

Actually no one wears Harris tweed much anymore. In fact, they never did, no one Larry ever knew. It’s vintage almost, like a costume. What happened was, Larry was about to graduate from Red River College (Floral Arts Diploma), just two guys and twenty-four girls. The ceremony was in the cafeteria instead of the general-purpose room, and dress was supposed to be informal. So what’s informal? Suits or what? The girls ended up wearing just regular dresses, and the two guys opted for jackets and dress pants.

Larry and his mother went to Hector’s, which she swears by, and that’s where they found the Harris tweed, this nubby-dubby wool cloth, smooth and rough at the same time, heavy but also light, with the look of money and the feel of a grain sack, and everywhere these soft little hairs riding on top of the weave. The salesman said: “Hey, you could wear that jacket to a do at the Prime Minister’s.” Larry had never heard of Harris tweed, but the salesman said it was a classic. That it would never go out of style. That it would wear like iron. Then his mother chimed in about how it wouldn’t show the dirt, and the salesman said he’d try real hard to get them twenty percent off, and that clinched it.

Larry wears the Harris tweed to Flowerfolks almost every day over a pair of jeans, and it’s hardly worn out at all. It never looks wrinkled or dirty. Or at least it didn’t until today when Larry put on this other jacket by mistake. So! There’s Harris tweed and Harris tweed, uh-huh.

It was an accident how Larry got into floral design. A fluke. He’d been out of school for a few weeks, just goofing off, and finally his mother phoned Red River College one day and asked them to mail out their brochure on the Furnace Repair course. She figured everyone’s got a furnace, so even with the economy up and down, furnaces were a good thing to get into. Well, someone must have been sleeping at the switch, because along came a pamphlet from Floral Arts, flowers instead of furnaces. Larry’s mother, Dot, sat right down in the breakfast nook and read it straight through, tapping her foot as she turned the pages, and nodding her head at the ivy wallpaper as if she was saying, yes, yes, floral design really is the future.

Larry’s father, though, wasn’t too overwhelmed. Larry could tell he was thinking that flowers were for girls, not boys. Like maybe his only son was a homo and it was just starting to show. In the end, he did come to Larry’s graduation in the cafeteria but he didn’t know where to look. Even when Mrs. Starr presented Larry with the Rose Wreath for having the top point average, Larry’s father just sat there with his chin scraping the floor.

Larry was offered a job right off at Flowerfolks, and he’s been there ever since. Last October he got to do the centerpieces for the mayor’s banquet. It was even on television, Channel 13. You saw the mayor standing up to give his speech and there were these sprays of wheat, eucalyptus branches, and baby orchids right there on the table. Orchids! So much for your average taxpayer. But Flowerfolks has a policy of delivering their flowers to hospital wards if their clients don’t want them afterwards, so it’s really not a waste. They’re a chain with a social conscience, and also an emphasis on professionalism. They like the employees to look good. Shoulder-length hair’s okay for male staff, but not a quarter inch longer. A tie’s optional, but jackets are required. That’s where the Harris tweed comes in.

Larry can’t help thinking how this new, new jacket will knock their eyebrows off down at work.

Or maybe not, maybe they won’t even notice. He hadn’t noticed himself when he picked it up, so why should they? What happened was he went up to the counter to order his cappuccino. Not that he had to order it. He takes the same thing every day, a double cappuccino. He used to go to a bar for a few beers after work, but Dorrie got worried about all the booze he was soaking up. She was convinced his brain cells were getting killed off. One by one they were going out, like Christmas lights on a string, only there weren’t any replacements available.

“Why don’t you switch to coffee?” she said, and that’s when Larry started dropping into Cafe Capri, which is just around the corner from Flowerfolks. A nothing place, but they’ve brought cappuccino to this town. Nobody knew what it was at first, and some people, like Larry’s folks, still don’t. Larry’s tried it, and now he’s on a streak with double cappuccinos. They start making it when they see him come through the door at five-thirty.

He likes to put on his own cinnamon. He likes it spread out thin across the entire foam area, not just sitting in a wet clump in the middle. You take the shaker, hold it sideways about two inches to the right of the cup and tap it twice, lightly. A soft little cinnamon cloud forms in the air – you can almost see it hanging there – and then the little grains drift down evenly into the cup. Total coverage. Like the dust storm in Winnipeg last summer, how it coated every ledge and leaf and petunia petal with this beautiful, evenly distributed layer of powdery dust.

Lots of coffee places have switched over to disposable plastic, but Cafe Capri still uses those old white cups and saucers with the green rims. You put one of those cups up to your mouth and the thickness feels exactly right, the same dimensions as your own tongue and lips. You and your cup melt together, it’s like a kiss. Customers appreciate that. They’re so grateful for regular cups and saucers that they carry their own empties up to the counter on their way out. That’s what Larry must have done. Taken his cup back up, put his fifty-five cents by the cash, and picked up a jacket from the chair. Only it was someone else’s chair. Or maybe the other guy had already made off with Larry’s jacket at that point. A mistake can work both ways. Larry was probably busy thinking about meeting Dorrie, about the movie they were going to see that night, Marathon Man, their third time, and then coming back to her place after, his prick stirring at the thought.

When they first started going together they’d be lying there on top of her bed and she’d say, “Let’s fuck and fuck and fuck forever.”

“Do you have to say that?” Larry said to her after he’d known her a couple of months. “Can’t you just say ‘making love'?”

She got her hurt look. Parts of her face tended to lose their shape, especially around her mouth. “You say ‘fuck,'” she said to Larry. “You say it all the time.”

“No, I don’t.”

“Come off it. You’re always saying ‘fuck this’ and ‘fuck that.'”

“Maybe. Maybe I do. But I don’t say it literally.”

“What?” She looked baffled.

“Not literally.”

“There you go again,” she said, “with those college words.”

Larry stared at her. She actually thinks flower college is college.

It was sort of a mistake the way they got together. Larry had taken another girl to a Halloween party at St. Anthony’s Hall. She, the other girl, had a pirate suit on, with a patch over the eye, a sword, the whole thing. And she’d made herself a moustache with an eyebrow pencil or something. That bothered Larry, turning his head around quick, and looking into the face of a girl wearing a moustache. A costume is supposed to change you, but you can go too far. Larry was a clown that night. He had the floppy shoes and the hat and the white paint on his face, but he’d skipped the red nose. Who’s going to score points with a red nose? There was another girl, Dorrie, at the table who’d come with her girlfriends. She was dressed like a Martian, but only a little bit like a Martian. You got the general idea, but you didn’t think when you were dancing with her that she was some weird extraterrestrial. She was just this skinny, swervy, good-looking girl who happened to be wearing a rented Martian suit.

“You in love with this Dorrie?” That’s what Larry’s father asked him a couple of months ago. They were sitting there in the stands. As usual the Jets were winning. Everyone around them was cheering like crazy, and Larry’s father said to Larry, not quite turning his face: “So, you in love with this girl? This Dorrie person?”

“What?” Larry said. He had his eyes on the goalie all alone out there on the ice, big as a Japanese wrestler in his mask and shin pads, putting on a tap-dance show while the puck was coming down the ice.

“Love,” Larry’s father said. “You heard me.”

“I like her,” Larry said after a few seconds. He didn’t know what else to say. The question set a flange around his thoughts, holding back his recent worrying days and nights, keeping them separate from right-now time.

“But you’re not in love?”

“I guess not.”

“You just like her?”

“Yes. But a lot.”

“You’re twenty-six years old,” Larry’s father said. “I married Mum when I was twenty-five.”

Like a deadline’s been missed, that was his tone of voice.

“Yeah,” Larry said. “Twenty-six years old, and the kid’s still living at home!”

He felt his bony face fall into confusion. And yet he loved this confusion, it was so unexpected, so full of thrill and danger. Love, love.

“Nothing wrong with living at home,” Larry’s father said, huffing a little, looking off sideways. “Did I say there was anything wrong with that?”

Larry was running this conversation through his head while he walked along Notre Dame Avenue in his stolen Harris tweed jacket, seeing himself in his self’s silver mirror. The fabric swayed around him, shifting and reshifting on his shoulders with every step he took. It seemed like something alive. Inside him, and outside him too. It was like an apartment. He could move into this jacket and live there. Take up residence, get himself a new phone number and a set of cereal bowls.

That’s when he realized he was in love with dopey smart Dorrie. In love. He was. He really was. Knowing it was like running into a wall of heat, his head and hands pushing right through it. This surprised him, but not completely. You can fall in love all by yourself. You don’t have to be standing next to the person; you can do it alone, walking down a street with the wind blowing in your face, a whole lot of people you don’t even know going by and they’re kind of half bumping into you but you don’t notice because you’re in a trancelike state. He forgot, suddenly, how Dorrie had this too-little face with too much hair around it and how he always used to get turned on by girls with bigger faces and just average hair size.

He looked at his watch, worried. He knew she’d still be standing there, though, next to the cash with her arms full of shoes and she’d be pissed off for about two seconds and then she’d get an eyeful of Larry’s jacket and before you knew it she’d be rubbing her hands up and down the cloth and fingering the buttons.

The problem, though, was tomorrow. Larry and his new jacket weren’t going to make it tomorrow. He could go to work in this jacket, but no way could he go back to the Capri at five o’clock. They’d grab him the minute he walked in. Hey, buddy, there’s a call out for that jacket. That jacket’s been reported.

Wait a minute, it’s all a mistake.

A mistake that led to another mistake that led to another. People make mistakes all the time, so many mistakes that they aren’t mistakes anymore, they’re just positive and negative charges shooting back and forth and moving you along. Like good luck and bad luck. Like a tunnel you’re walking through, with all your pores wide open. When it turns, you turn too.

Larry remembers seeing a patient in the Winnipeg Chronic Care Unit when he delivered the flowers after the mayor’s banquet. This guy didn’t have any arms or legs, just little buds growing out of his body. He was one bad mistake, like a human salt shaker perched there on the edge of a bed. Larry, set the flowers down on the table next to him, and the guy leaned over a couple of inches and brushed them with his forehead, then he smelled them, then he stuck his tongue out and licked the leaves and petals, all the while giving Larry a look, almost a wink but not quite. Larry took a lick too, lightly. What he found was, eucalyptus tastes like horse medicine. And orchids don’t taste at all.

The sun was dipping low, and Larry was at the corner now, only half a block from Shoes Express. There was a great big rubbish receptacle standing there with a sign on it: Help Keep Our City Clean.

Larry unbuttoned the Harris tweed jacket, slipped it off fast and rolled it up in a sweet little ball. He stuffed it into the rubbish bin. He had to cram it in. He didn’t know if he was making a mistake or not, getting rid of that jacket, and he didn’t care. The jacket had to go.

And that’s when he really knew how cold the wind had got. It puffed his shirt-sleeves up like a couple of balloons, so that all of a sudden he had these huge brand-new muscles. Superman. Then it shifted around quick, and there he was with his shirt pressed flat against his arms and chest, puny and shrunk-up. The next minute he was inflated again. Then it all got sucked out. In and out, in and out. The windiest city in the country, in North America. It really was.