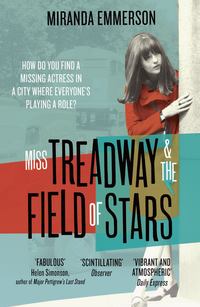

Miss Treadway & the Field of Stars

She thought about Lanny’s story of her father, her mother and then her brother dying. She was the very last of her little family. Surely she was meant to carry on – to have children, even. Iolanthe was forty but it might still be possible. If she met someone soon she could have the chance of a child. Maybe she could adopt. She had asked Lanny once about men: was there anyone, was there someone back home in the States?

‘I’ve never been a great one for relationships. And I’m not too good at sex and nothing else. I grew up really fast, really young. Went straight over that drippy crush stage and into the cold, hard world. Men are dangerous, Anna, you never know what they’re really thinking.’

‘I suppose. I’m not any good at relationships either. I quite like having my own life.’

‘That’s it. That’s it exactly. I have my life.’

‘Miss Treadway? Is it miss?’ A tall man carrying a bunch of folders under one arm was calling her from across the hallway. She raised her hand, nerves rendering her momentarily dumb. The red-haired policeman advanced on her with an outstretched hand: ‘Good morning, miss. I am Detective Sergeant Barnaby Hayes. We’re in interview room four. Would you follow me, please?’

Anna followed Hayes along a beige corridor and then another. In the distance she could hear the murmur and rattle of a works canteen, but for the most part the station was oddly silent. Voices murmured and muttered behind half-closed doors; file drawers squeaked and rolled in and out in offices as they passed.

‘Here we are.’ Hayes knocked on the door and when no reply came back they entered. The room was windowless, but held a table and three chairs. The walls were painted pistachio green and the floor was black linoleum.

‘Cup of tea?’ Hayes asked.

‘Yes. Please. Milk, no sugar. No, actually, sorry … sugar please. Two.’

‘It’s comforting, isn’t it?’ Hayes smiled at her. ‘June!’ he cried down the corridor and a door somewhere unseen opened.

‘Yes, Sarge, what’ll it be?’ a voice came back.

‘Two teas for interview room four, please. Normal for me. Milk and two for the young lady.’

‘Your wish is my command.’ Hayes shut the door.

Sergeant Hayes spread the folders out in front of him and pulled out half a dozen forms and bits of paper.

‘Now, I wanted to go back over your statement and then I also wanted to ask you about this interview. The one from The Times.’

‘I was there for that. I was in the room.’

Hayes blinked at Anna with a look that signalled genuine interest. ‘Right. Well … First things first. Would you describe Iolanthe Green as a stable person, Miss Treadway?’

‘Define stable.’

‘Really?’

‘I mean, how stable is stable? She was stable enough … in the grand scheme of things. But she was human. I mean, she was a bit highly strung and a bit, um, prone to moodiness. But then, when I say these things sitting in an interview room, they suddenly sound much more serious, much more terrible, than I think they are. She was … there’s no good way I can put this … she was female and she had female insecurities and she was an actress and she had those insecurities too but that makes it sound like I’m trying to say she was mad when really I just think she was rather ordinary.’

‘So, you’re saying she was essentially ordinary?’

‘Yes. Ordinary woman. Ordinary hang-ups. Ordinary … intelligence. You know, Sergeant …’

‘Hayes, miss.’

‘You know, Sergeant Hayes, actors and actresses are very, very ordinary people. They do a job and half the time the people around them yelp like castrated cats, howl with pleasure and tell them that they are the saviours of the world. But most of them, the ones who don’t let the publicity drive them mad, know that they are very ordinary people, with a basic technical ability: like a plumber or a welder. Except that half the world has decided that this type of welding is akin to performing miracles.

‘Iolanthe wasn’t clever. Not book clever, I mean. But she wasn’t stupid either. She knew that what she was involved in was a kind of popular conjuring trick. And she knew that her career would be finite and that she had to make the best of it and save for the future. She didn’t spend her money on fancy things. The Savoy gave her that room for publicity. She was sent clothes by department stores and designers. She wore costume jewellery and never caught a cab if she could help it. She told me once that she had been born into poverty and had half a mind that she would die that way too. She took her money and she sent it back home. Every month, every shilling she could spare, she squirrelled it away somewhere.’

There was a knock and Hayes rose to let in June, who was carrying two cups and saucers.

‘’Bout time too,’ he noted drily.

‘Up your bottom, Sarge,’ said June, winking at Anna, who was slightly outraged at this piece of rudeness in such an austere setting.

As June shut the door behind her Hayes started to arrange the papers into a chequerboard in front of him.

‘You spoke about Miss Green sending money home to be deposited. And we have talked with Miss Green’s agent in New York and with their in-house accountant who very kindly gave us select details of the accounts Miss Green deposited her earnings into. Now I don’t have a record of amounts but I do know that over the years Miss Green deposited money into a series of accounts with a variety of names attached to them. We have three accounts in the name of Iolanthe Green. One account in the name of Yolanda Green. Two accounts in the name of Nathaniel Green. And one account in the name of Maria Green. Would you happen to know anything about these other names, Miss Treadway?’

‘Well, Nathaniel was her brother but she said … I heard her say that he died in ’45 or ’46. Just after the war … in Japan. He had a car accident.’

‘And yet he has two savings accounts still open. One held at a bank in Boston and the second at a bank in Annapolis, Maryland. Any ideas?’

‘None. She always said she had no family … Her mother and her father died in the forties or late thirties and her brother died just after. There wasn’t anyone else … though I suppose aunts and uncles?’

‘Her agents knew nothing about her wider family, it seems. They only have addresses and phone numbers for Iolanthe herself. They never met anyone else from her family. Though we have to suppose, given the shared surnames, that all these people belong to the same family. In the interview she said she came from Cork.’

‘Her grandparents came from Cork. She’d never been there. I never saw a card or a letter in the dressing room that looked like it came from family … I mean, she got them from fans, from other actors, from her agency, from the studios she’d worked with …’

‘Did you notice anything which might suggest that she was in contact with people in Ireland? Did she want to visit Ireland? We’re wondering if … well, sometimes people find themselves under pressure and they run. We’re wondering if Miss Green might have run away to Ireland.’

‘To be honest she’d never mentioned the place. Not before the interview.’

Hayes smiled and changed the subject. ‘I gather she was a big star but I have to confess I’d never heard of her. Perhaps I recognised her face …’

‘She is a star … of a sort. She’s had top billing in at least one film. But she isn’t Julie Andrews or Elizabeth Taylor. And she probably made it too late. If you’re a woman you have to make it at twenty and then stay there and even then … It’s a very uncertain business. My theatre manager, Leonard, he says she’s got maybe another three years in pictures and then she’ll need a stage career. That’s why her agent wanted her to do this play.’

‘Was she depressed about all this? About the uncertainty of it all?’

‘She never said she was. She always seemed very philosophical about it. She just wanted to work. I mean, she worried about money. She always worried about money.’

‘This interview she gave … have you read the transcript? I mean the bit they printed in the paper.’

‘Not really. I was there for nearly all of it and it rather annoyed me. The way they printed it after they knew she was missing.’

Hayes drew out a newspaper cutting.

‘I’m going to read from it. I want you to tell me if anything might have been left out, or added, or if there’s anything you don’t remember her saying … Okay. There’s a load of silliness at the beginning: “lies back on her green velvet chaise longue”, “tale of heartbreak and longing”, blah blah blah. Then it begins. “Wuthering Heights was my big break, though. It really made my name. From my humble beginnings among the Boston Irish I could never have imagined I’d be so successful in Hollywood. California seemed like another planet, not where a girl of my humble origins belonged at all.” How does it sound so far?’

‘Well, the gist of it makes sense. I don’t remember Iolanthe saying it quite like that and he’s leaving out a lot. But it’s sort of rightish.’

‘Okay. She goes on: “In many ways I’m doing all of this for my little brother Nate. He was killed in Japan at the end of the war and it broke all our hearts. My poor mother never got over the shock of losing him. By the age of twenty-one I was all alone in the world.” Okay?’

‘I’m pretty sure her mother died before her brother did. The chronology’s wrong.’

‘Anything surprising?’

‘Not really.’

‘“I ask Miss Green about her connections with Ireland. ‘My grandfather’s family – the Callaghans – claimed to have pledged allegiance long ago to Perkin Warbeck when he made his claim to the English throne. And I like to think that a piece of that rebel heart lived on in all of us, helping us to fight a little harder for the things we believe in.’” How’s that?’

‘I can’t imagine Iolanthe knowing who Perkin Warbeck was. But … I don’t know. They did talk about Ireland. And I was cleaning things and moving around. Maybe I wasn’t paying enough attention.’

‘It goes on: “I ask Miss Green what she’s enjoying most about her time in London. ‘Oh, James, it’s hard to choose. I’ve lived in Boston and New York and Los Angeles but there’s something really special about London. Some magic ingredient. I think it’s the coming together of so many different, vibrant people all in one spot. I’ve loved the parties I’ve been invited to here: at Ronnie Scott’s, the Marquee and the Flamingo. The music you have in England is amazing. I think there’s something in the Celtic heart that responds to that beating of drums, that essential rhythm of the night.’ I tell her that our diarist was thrilled to spot her coming in and out of Roaring Twenties on Carnaby Street on several nights last week, but Miss Green just blushes and stands to fix her make-up. She has another show to do. I let her rebel heart prepare.”’

‘Yuck.’

‘Well, yes. But is it accurate?’

‘I’ve no idea. I didn’t know Iolanthe went to clubs. As far as I was concerned she was trotting off back to The Savoy every night at eleven. I don’t … I’m sorry. I can’t honestly say that she didn’t mention this because I might have missed it, but it doesn’t bear much resemblance to the conversation I heard.’

Barnaby Hayes stared down at the clipping in front of him and wrinkled his brow.

‘Is that helpful?’ Anna asked.

Hayes looked up at her and smiled a smile of frustration. ‘Well, it’s all helpful if it’s true, isn’t it?’

‘Is it, though? Does it get you any closer to what happened to her?’

‘The thing about truth, Miss Treadway, is that it’s not always the friend of narrative. My job is to figure out your friend, Miss Green, and to construct a likely narrative that will help us to determine if she left of her own free will or was taken. And there are two ways I can go about this. I can invent a number of plausible narratives and try and hold them up against the facts until I find the one that fits. Or I can listen to all the facts – with no particular narrative in mind – and then assemble the known knowns in such a way that they reveal the basic truth of the matter.

‘And I have to tell you that in my experience the human brain only wants to do the former. It wants to think like a scientist. Hypothesis. Experiment. Results. It doesn’t want to look at all the facts in all the world and wait for a pattern to emerge. Because that is a ridiculously hard thing to do. It’s the sort of thing that only geniuses can achieve. Normal people need a narrative. And currently your Miss Green refuses to offer much of one.’

‘Why do women usually go missing?’

‘Because their husbands beat them. Or they have affairs and decide to run away. Some of them are murdered. But not many. Mostly it’s violence. At home.’

Anna watched Hayes scanning the pieces of paper and was briefly jealous of the job he did. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d been asked to use her mind for anything much at all beyond the dressing and undressing of actresses.

Hayes sighed. ‘Let’s go back to the names. Yolanda, Nathaniel, Maria. We know Nathaniel was the brother. Killed in Japan. Yolanda and Maria?’

‘Well, one of them must be the mother. Or an aunt.’

‘But if they’re dead …’

‘… then why is she giving them her money?’

‘Unless it’s just tax avoidance.’ Hayes shook his head then he looked Anna hard in the eye. ‘You talked to Iolanthe more than most, didn’t you?’

‘Probably. At work anyway.’

He tore a piece of paper off the bottom of one of his notes and wrote down two numbers on it.

‘This one’s work. This one’s home. If you think of something; doesn’t matter what. Ireland. Names. Clubs. Money. Men. Will you call me? Please? I would like to find her alive.’

Anna took the slip of paper and filed it in the pocket of her handbag. Then they sat for a moment in the silence of the room, looking at each other. It occurred to Anna that there was an odd kind of intimacy to a police interview. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d been alone in a room with a man, certainly not a man who looked to be the same age as she was.

Hayes gave her a slightly embarrassed smile. ‘I hope we find her,’ he said. And then he stood and almost seemed to be bowing but offered her his hand instead. Anna took it and shook it and wished that her own wasn’t so slippery.

‘It was nice to meet you, Sergeant Hayes.’

‘And you, Miss Treadway.’ Hayes opened the door to let her out into the corridor.

***

On Sun Street, Orla and Gracie made oatmeal biscuits because having the oven on made the kitchen warm and then Gracie drank milk at the table and drew a monster in blue and purple crayon with eyelashes that licked the edges of the page. Orla made them toast and beans for lunch and drank cup after cup of tea to ease the passing of the hours.

After lunch they bundled up in everything woolly they owned and went to watch the trains in Liverpool Street station. When Orla had the money she would treat Gracie to a cup of hot chocolate from the buffet or a tube of fruit pastilles from W. H. Smith. In leaner months she would pack a little picnic of biscuits or butter sandwiches and they would wait for a bench to perch on and play I Spy and Twenty Questions and Botticelli – the characters in the latter taken entirely from the pages of children’s books, for Gracie only knew the worlds of Andersen and Grimm and Lewis.

‘Are you a princess but only after marriage?’

Gracie thought about this. ‘No,’ she said at last, ‘I’m not Cinderella.’

‘Are you furry and mistaken for a witch?’

‘What’s that?’ Gracie frowned at her mother as if Orla was being grown up and clever just to annoy her. ‘I don’t know.’

‘The cat. Musicians of Bremen. The robbers think she’s a witch. I’ve got a proper question! Are you royal?’

‘Yes,’ said Gracie with a haughty arch of one eyebrow, ‘I’m a queen.’

‘Of course. Okay, okay. Did you send your neighbour a little gift which could have doomed him?’

Gracie blinked and stared out towards the chuffing, chugging, waiting, steaming trains and watched the great black hands of the great white clock sweep round. Orla felt a pang of regret that she had made the question so hard because she could feel sadness leaking out of her daughter. Was she – as a mother – meant to coddle her daughter or challenge her? She never really knew for sure, so in her own haphazard way she would do first one then the other, just as she felt inclined at that moment in time.

‘I don’t know,’ Gracie said in a very small voice.

‘Sorry. Was that mean? I’m the Emperor of Japan with his mechanical nightingale.’

‘Okay,’ said Gracie, clearly fizzing with annoyance. ‘Have another question.’

‘Are you queen of a dying world?’

Gracie fixed Orla with a long, withering look. ‘Yes, clever Mummy. I am Queen Jadis and you win …’ she threw her arms up towards the ceiling, ‘everything.’

‘You’re really narked with me, aren’t you?’ said Orla.

‘You make it too hard. I’m four.’

‘I know. Mammy knows.’

‘You shouldn’t make me cross.’

‘Shouldn’t I?’

‘I can make the world blow up.’

‘Really? And how do you do that?’

‘I say the deplorable word.’

‘Well, you should do it. Go on, Gracie, blow it all to bits. Just tell Mammy one thing first. What is it?’

‘Bum,’ said Gracie. ‘Bum is the deplorable word.’ And she held her mother’s stare for half a minute until Orla’s face cracked into a bright-toothed smile.

The men in their camel-coloured coats swept past and the trains honked and blew out steam that seemed to scorch the cold air above their heads. Mother and daughter held hands and watched all the people in the world pass by, aware only of the features and topography of their strange and dazzling bubble life together.

Not Going Out

Tuesday, 9 November

At half past ten Rachel brought the remaining customers their bills on little silver plates with tiny pieces of Turkish delight around the edges. At ten to eleven Ottmar turned on the main lights in the coffee house, flooding the space with a harsh yellow glow. By five past eleven the bills had been paid and Ottmar was ready to lock the doors.

Rachel and Helen cleared the tables, blew out the candles, stacked the plates by the sink and started to sweep and scrub the restaurant clean. In the kitchen Mahmut scoured the surfaces and washed down the hob. Ottmar brought the radio up to the hatch and tuned to the Light Programme for the last hour of Jazz Club. All but one of the overhead lights was turned off and the cafe sank back into a gentle night-time space where the silver mirrors on the walls threw strange shafts of light across the floor and the ghostly, mesmeric sound of Stan Tracey playing ‘Starless and Bible Black’ seemed to echo, bounce and flutter against every wall. The people in the cafe moved slower now, feeling the night soaking into them, filling their arms and legs with darkness and a dreamy quiet that felt like drunkenness and sleep.

Ottmar sat on a stool at the counter behind the hatch and arranged in a series of little metal bowls a late supper of eggs and flatbread and spinach and yoghurt. He cut up the end of the coffee cake and arranged a pyramid of squares on a blue china plate and then he carried the plates and the forks and the dishes of food and laid them out on two of the longer tables which he pushed together.

He noticed a blank, black human shape standing at the glass doors to the front.

‘Helen!’ Ottmar called and Helen let Anna in. Ottmar waved his hand for Anna to join him at the table as the others cleaned and swept around him. Anna pulled off her coat and gloves and scarf and flung them down over the back of a chair.

‘How are you doing today?’ Ottmar asked.

The question made Anna want to cry, though she didn’t really know why. ‘I went to look for her.’

‘For Iolanthe?’

‘I walked the Strand and the banks of the river … past The Savoy. I looked for her in St Paul’s Cathedral. I had this sense of her seeking refuge from something. I walked in there and I started to believe that I would see her sitting at the end of a pew or hiding in the shadows. But once I’d looked around it didn’t feel like somewhere where anyone would go seeking refuge. So much grandeur. So much pomp and frilly woodwork, lights and gold. It looked like a theatre. And that’s the last place Lanny would run.’

‘You’re sure she ran away?’ Helen asked her.

‘I have to believe it.’

‘From what, though?’

‘From us?’ Anna shrugged. ‘I don’t know. Money trouble.’

‘Men,’ said Rachel.

Anna shook her head. ‘I went to meet a policeman today and he asked me questions and he showed me the interview Lanny did and it’s full of mistakes so I don’t even know if we can trust it but it said she’d been going out to the clubs. Like the jazz clubs and the ones down Carnaby Street.’

‘Does that seem likely?’ Ottmar asked.

‘Not really. She never even talked about clubs or music or men or any of that. But then the man from the paper claimed that she’d been seen coming out of Roaring Twenties more than once.’

Helen and Rachel threw their rags and brushes into the corner of the kitchen, stripped off their aprons and used the edges to scrub the smell and slick of grease from their hands. Mahmut brought out a pot of coffee and a bowl of sugar and sat at the end of the table slapping his face violently with his hands as if to beat out the tiredness. The music from the radio changed and now the notes rippled through the air like the smell of grass on a clear spring day. The lights seemed to burn a little brighter above them and slowly, imperceptibly, the pace of their movements changed. Anna poured herself a cup of coffee and ate a plate of spinach and yoghurt, which tasted like midsummer and helped to draw the chill from her bones.

Ottmar’s mind drifted free of the assembled group and took him back to Melanippus’s vast living room in Nicosia with its white marble floor and long dark leather seats. In a former life he’d written book reviews for a Greek magazine in his native Cyprus. The only Turk on the staff, he’d spent his evenings smoking cigarettes and talking about art and philosophy and life with all the other twenty-somethings who dreamed of flying away to a life of avant-garde delights in Paris or Berlin. Melanippus, the editor, would play jazz until four in the morning: Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Artie Shaw. Ottmar had so desperately wanted to belong and for a little while he had. And now, here in his cafe at midnight with The Harry South Big Band playing ‘Six to One Bar’, he knew that he was not quite locked out of that world; just downgraded to a cheaper room.

Anna had sunk into a kind of sulk. Her broad shoulders fell forward and she stared at the corner of the table while her fingers worked apart a piece of bread. ‘It’s too strange, Ottmar. We talked every day. But then I think about the things we talked about and there’s her clothes and her looks and we joked about men and people in the company but she never told me anything about … before. Where she came from. Everything was always in the present. She never mentioned family. She never mentioned her past.’

Ottmar made a slight face as if to say that Iolanthe was not the only one. Anna chose to ignore this. ‘She had all these bank accounts in different names. Maria and Yolanda and Nathaniel. Nathaniel, her brother, isn’t even alive any more – but she’s paying money to him all the same.’

Ottmar frowned. ‘You mean Iolanthe?’

‘What?’

‘You said Yolanda.’

‘Well, yes. She was Iolanthe but she paid money into the bank account of a woman called Yolanda Green.’

‘But they’re the same name. Iolanthe is a Greek name, yes? But in Spain, she’d be Yolanda. Iolanthe; Yolanda: same name.’

‘Oh.’ Anna was taken aback by her own ignorance. ‘I didn’t realise. I … Thank you.’ She stared at Ottmar and he couldn’t quite read the emotion in her look. ‘I went to the police station today and it felt real again. And I realised that all those stories, all those articles and interviews, they’d turned this thing – Lanny’s disappearance – into something else. They took it over. Made it unreal. I’d come to feel that Iolanthe belonged to some other world. A world of newspapers and radio. Almost as if she wasn’t real. Wasn’t our problem. But she is real. And she is our problem. She was this person that I knew and liked … and something horrible has happened to her.’