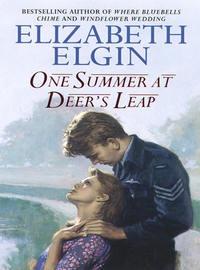

One Summer at Deer’s Leap

‘She’s made an impression on you, hasn’t she, Jeannie?’

‘Mm. Pity I can’t write. I wouldn’t mind ending up like her.’

‘Filthy rich?’

‘Y-yes. But more the way she looks and is. She’s obviously getting on, but it doesn’t show somehow.’

We had reached the top of the rise now, and stood without speaking, to stare. The sun was beginning to go down and there was a hint of chill in the air. It made me remember that in a week it would be September, with autumn not so far away.

‘Have you taken in all you want of the view?’ Jeannie teased. ‘Because I think we should start back. It’s turned quite cold.’

‘Yes, but I’ll come here again with a camera.’

Not that I would need reminding of that one summer at Deer’s Leap. I would always remember it, and wonder who was living there, and worry too about Jack Hunter and that I hadn’t been able to help him find Suzie. How long would he wait at that gate for her? Into forever? It made me swallow hard on the sentimental tears in my throat.

‘Hey! You there!’ I heard the snapping of Jeannie’s fingers under my nose and shook my head clear of the pilot. ‘You were miles away!’

‘Years away, if you must know. Do you realize I’ve got little more than a week to find where the Smiths went when they left Deer’s Leap?’

‘So you were thinking about the pilot again?’

‘Suppose so. It looks as if I’m not going to be able to help him, for all that.’

‘You mean you’ve been serious all along about finding Susan Smith?’

‘I – I’ve wondered about it quite a bit …’

‘Then I don’t understand you, Cassie Johns! I can’t even think you’d waste good writing time chasing after a woman who probably won’t remember Jack Hunter – even if she’s still alive!’

‘She is alive, I know it! And she won’t have forgotten him.’

‘But she could have married someone else, for Pete’s sake! And if she hasn’t, what are you going to say to her, “Excuse me, Miss Smith, but there’s a ghost looking for you!”?’

‘OK, Jeannie! I agree with everything you say and it will be difficult.’

‘But if you find this Susan Smith are all your troubles over? The heck they are! Have you just once stopped to think you can’t take up residence at the kissing gate with an elderly lady, waiting for a ghost to turn up?’

‘We-e-ll, I suppose –’

‘No supposing, Cassie! Jack Hunter is none of your business and neither is Susan Smith! You can’t go poking and prying into things that don’t concern you. Leave it! Take the lid off that one and you don’t know what you’ll find. Nasty wriggling maggots, I shouldn’t wonder!’

‘You’re right, I’ve got to admit it, yet –’

‘Too right I’m right! Say you’ll forget it?’

‘OK! I’ll forget it!’

‘And you really promise, Cassie? You’ll let well alone?’

‘I just said so!’

I stuck my hands in my pockets and whistled to Hector, and it was only when we were manoeuvring ourselves through a kissing gate that didn’t squeak and wasn’t in need of a coat of paint that I knew I had no intention of keeping my promise, even though I might well be taking the lid off a tin of maggots.

Sorry, Jeannie!

We drove to the village next morning and the familiar feeling took me as we neared the straight stretch of road and the clump of oaks. But the airman didn’t show and I was reluctantly glad, because I didn’t want Jeannie messing up our encounter, and she would have.

I parked behind the Red Rose and left her to do the shopping, making for the phone box. Mum seemed pleased to hear from me and straightway asked if Piers had phoned lately.

‘Phoned! He turned up on Thursday, bold as brass!’ I told her what had happened. ‘He left in a huff,’ I finished. ‘I was so mad, the way he got my address!’

‘Mm. Sneaky. Mind, he was always a spoiled child. Maybe you’re well rid of him after all! You’ll be home, next week?’

‘Yes, but I’m not sure when. Is Dad about?’

‘He’s at the bottom of the garden, pricking out lettuces. Take too long to fetch him. I’ll give him your love.’

‘Do that, Mum. Anyway, the card has almost run out! I’ll ring on Wednesday.’

‘Don’t bother. I’ll ring you. Save you going out. Now don’t forget to check the doors and windows at night, and don’t answer the door after dark!’

I put the phone down just as Bill Jarvis walked past to stand at the bus stop, and I smiled at the lady by his side.

‘Now then, Cassie!’ he grinned. ‘How have you been lately? This is our Hilda.’

Hilda held out a hand and said she was pleased to meet me. ‘You’re interested in the Smith lass?’ she said without preamble.

‘Yes, but not in a nosy way,’ I said earnestly. ‘More how it was for people like her in the war. It couldn’t have been very nice, getting thrown out of your home.’

‘A lot about that war wasn’t very nice. Mind, I’ve got to be fair. I found a husband and I wouldn’t have done in the normal course of events. Young men were a bit thin on the ground in Acton Carey before the Air Force came. What do you want to know about Susan Smith?’

‘Nothing in particular – just anything you can tell me, Hilda. What did the RAF do with Deer’s Leap once they’d taken it over? I just can’t believe some man from the Ministry could knock on a door and say the occupants had to get out! There’d be an outcry if it happened now, and protesters everywhere!’

‘Happen so, lass, but when there’s a war on things are a mite different. Weren’t considered patriotic to protest in those days. But it isn’t me you should be talking to about Susan Smith. There were two years’ difference in our ages and that’s a lot when you’re young. Lizzie Frobisher as was would know more about her than me. Those two were close; both of ’em went to Clitheroe Grammar on the school bus every day. They’d be about fourteen when the war started. Lizzie’s dad worked for Mr Ackroyd at the Hall. She married a curate when the war was over.’

‘I see.’ The one person who could tell me about Susan could be anywhere now. ‘Do you know where she went?’

‘Aye. Somerset.’

‘Pity. I’d have liked to talk to her. I still want to see the church, though. Will it be all right if I pop in next Friday?’

‘Feel free. But about Lizzie. Her name’s Taylor now, and –’

‘Look! There’s your bus!’ I cut her short, which was very rude of me but I didn’t have a lot of choice. Jeannie was making towards us and we’d agreed that the Deer’s Leap affair was taboo. Saved by the Skipton bus!

‘What was all that about?’ Jeannie frowned. ‘Been asking questions, have we?’

‘Yes. About the church.’ My gaze didn’t waver. ‘I’m going to look at it on Friday morning – that’s when the ladies clean it.’

‘And why are you interested in the church?’

‘Because anything about Acton Carey interests me.’ I didn’t blush nor feel one bit ashamed. ‘You’re in a very suspicious mood, if you don’t mind me saying so.’

‘No, I don’t.’ She looked up at the church clock. ‘It’s a bit early for a drink. Would you like to hang around and eat at the Rose when it opens? We could have a look at the church while we’re waiting.’

‘No thanks. Best get back.’ I was almost sure she was calling my bluff. ‘We said we’d cut the grass today as soon as it was dry enough, don’t forget.’

‘So we did. I feel like a bit of exercise. We can see this off,’ she held up a bottle of wine, ‘when we’ve finished. As a reward,’ she added solemnly.

Chapter Nine

On Friday morning I drove into Acton Carey, a last, sentimental journey. I would take a look at the church, then buy Bill a pint, if he was around. Say goodbye. Because since this morning I had a feeling that I would never come back, never see Deer’s Leap again. And maybe it was better that way; better to forget Jack Hunter and that war, and anyway, I decided mutinously as I drove past the clump of oaks, why should I bother my head about a ghost who didn’t have the decency to turn up when he must surely have known I would soon be leaving here. For ever!

I still felt piqued as I parked the car, then made for the war memorial, to stand there, staring fixedly at the name J. J. Hunter, asking silently why he hadn’t been there this morning, wishing I had brought flowers as a kind of goodbye. Flowers from Deer’s Leap garden; a bunch of the red roses that grew up the wall and peeped in at the kitchen window! It was a very old plant with a thick, gnarled stem that could even have been there when Susan slept in the room above the kitchen! Why hadn’t I thought?

‘I’m going home on Sunday,’ I whispered in my mind to the name chiselled there. ‘I’m sorry about what happened to you and Susan and I’m sorry I wasn’t able to help you. But I won’t forget either of you. One day, somehow, I’ll find how it was for you both …’

I blew my nose sniffily, then walked to the grandiose church, built to the memory of a cotton broker from Manchester whom almost everyone had forgotten, blinking my eyes to accustom them to the gloom, inhaling the churchy smell of dampness and musty books and dusty hassocks.

‘Hullo, love! Over here!’

I turned in the direction of the voice.

‘You came then!’ Hilda stood beside the lectern, waving and smiling.

‘I said I would.’

‘Happen you did, but you went off at a right old lick; didn’t give me time to tell you that –’

‘Your bus was coming.’ So too had been Jeannie! ‘I hope you didn’t think me rude.’

‘Nay. All I’d been going to tell you was that Lizzie Frobisher lives in Acton Carey.’

‘She lives where?’

‘At the vicarage. We don’t have a parish priest in the village any longer – all a question of money. Any road, there was a vicarage standing empty, so the Diocese made it into four flats for retired clergy. It was nice that Lizzie was able to come back to the village to live out her time. She’s over yonder, in the green cardigan.’

Here! Dusting pews no more than ten feet away!

‘Susan Smith’s friend?’ I whispered. ‘The one she went to school with?’

‘That’s the lady you should be talking to. Away over, and have a word with her. She’s Lizzie Taylor now.’

‘Did you tell her I was asking?’

‘No. But there’s none better to tell you about Susan.’

‘You don’t mind? I really came to look at the church …’

‘Then ask Lizzie to show it to you!’

Glory be! With only two days to go, I’d found Susan’s long-ago friend!

‘Mrs Taylor?’ I coughed loudly and she spun round, looking at me over the top of her glasses.

‘It is. And who might you be?’

‘I’m Cassandra Johns. I’m staying at Deer’s Leap.’

‘Ah, yes – you’ll want to talk about Susan?’ she said matter-of-factly.

‘I do, actually. But how did you guess?’

‘Ha! The whole village knows. Tell Bill Jarvis and you might as well tell the town crier!’ She pulled down the corners of her mouth and I took in her hand-knitted cardigan, the skirt gone baggy round the hips, the thin hair, permed into corkscrew curls. ‘Why are you interested in Susan Smith?’

‘I – I’m not especially. It’s Deer’s Leap really. I’m a novelist, you see, and I’m interested in anything to do with the place.’

And may you be forgiven, Cassandra Johns, for lying through your teeth in church!

‘Ah. An historical novelist! Then you can’t do better than write about Margaret and Walter Dacre – if you dare! Local folklore has always had it, you see, that those two were the worst of the bunch – the Pendle Witches, I’m talking about – but were never found out!’

‘Margaret Dacre?’ Oh, lordy! Aunt Jane had got it right! ‘The 1592 one?’

‘That’s her! Legend has it she worked spells and heaven knows what else. She got away with it too! I suppose people hereabouts were too afraid to shop her to the witch-hunters.’

‘But how do you know all this? I’ve never come across any reference either to her or to Deer’s Leap.’

‘You wouldn’t. Nothing was put on record; just handed down through the generations, sort of. But Mistress Dacre got her comeuppance, for all that. Seems she wanted to found a dynasty; pass that fine house on to her son, but she never conceived. The Lord’s punishment on her, if you ask me! But what’s got into you? You look quite odd, Miss Johns. Stupid of me talking about witchcraft, and you alone in that house. Let’s go outside for a breath of air? I’ve had enough dusting for one day. Feel like a cigarette?’

‘I – I don’t smoke.’ I followed her in a half-daze.

‘Afraid I do! A habit I picked up in the war, and never managed to kick!’ She settled herself on a bench beside the church porch and dug into her cardigan pocket. ‘But we can’t all be perfect, can we? Sure you don’t want one?’

‘Quite sure, thanks. But I really can’t imagine a witch ever having lived at Deer’s Leap. To me, it’s a beautiful old place. I’ve been alone there for days on end and never picked up one bad vibe – er – funny feeling.’

‘It’s all right.’ She inhaled deeply, eyes closed. ‘Vicars’ wives know what vibes are! Mind, there was often an atmosphere at Deer’s Leap – Mrs Smith’s fault, I reckon.’

‘Why? Wasn’t she happy there? Was it too isolated for her?’

‘I don’t think so. She just kept herself to herself. Not like in the village. No one locked their doors in those days. People just walked in without waiting to be asked. Mind, Susan’s father was a decent chap, though they weren’t much missed when they left.’

‘Then can you tell me,’ I whispered, ‘where they went when the Air Ministry took the house off them?’ My mouth was suddenly dry and my tongue made little clicking sounds as I spoke. ‘You and Susan would keep in touch?’

‘Well, that’s just it! It was as if they’d done a moonlight! One day they were there; the next day not a sign of them, and the place deserted. I know because I had arranged to meet Susan and she didn’t turn up. I went to Deer’s Leap looking for her because it was – well – rather urgent.’

‘And they’d vanished? All the livestock gone?’

‘Everything! I was hurt when Susan never wrote; not one line to tell me her new address, and she and I so close! I wonder to this day why she never got in touch. It was the talk of the village at the time; a nine-day wonder. No end of speculation, but no one ever found out. Susan never came back after the war. I’d have thought she’d have brought flowers or a poppy wreath to the memorial. It was as if Jack Hunter had never existed for her.’

‘Jack was her boyfriend,’ I said softly.

‘He was her whole life! They were so in love; right from the night they met. Mind, it wasn’t easy for them to meet, the way things were. It wasn’t on, going out with an airman, so I did all I could – gave Susan an alibi, sometimes …’

‘And the other times?’

‘She’d slip out of the house. When it was winter and dark before teatime, it was easier for her. He’d walk all that way, just to have a few minutes with her at the gate, then afterwards, in the barn.’

‘Was the aerodrome far away?’

‘About two miles from here. It was nearer to Deer’s Leap, actually, than to the village. That’s why the RAF took Mr Smith’s fields when they wanted to extend.’

I looked at the ash on her cigarette end. It clung there, more than an inch long and I waited, fascinated, for it to drop, thinking how steady her hand must be.

‘My mother said that in those days, girls didn’t have the freedom my generation has. I can’t understand it.’

‘I can! A girl obeyed her parents until she was twenty-one. That was when young people came of age in my day. Do you know, there were boys of twenty flying those huge planes. Old enough to drop a bomb-load on Germany and kill God knows how many, but not old enough to marry without permission! It was mad!’

‘What would have happened if Susan’s mother had found she was meeting an airman?’

‘She did know eventually. There was ructions!’

‘But couldn’t they have met sometimes when Susan left work? Didn’t she ever think to say she was working over-time?’

‘She never had a job; leastways only at home. She helped in the house and on the farm. Farming was work of national importance; so important it kept you out of the Armed Forces! Susan would have liked to join up, but it wouldn’t have been any use her trying. I felt sorry for her. It must have been awful, once she left school, with no one her own age to talk to for days on end.’

‘I’m surprised she ever got to meet her young man!’

‘She wouldn’t have, in the normal course of events, but there was something on in the village, I remember, to do with the church, and she stayed the night at our house. My mother had to practically beg permission. Susan’s mother said she couldn’t go, them not being Church of England, but Mr Smith said she could. He was a quiet man really, and hadn’t a lot to say for himself, but if ever he put his foot down, his wife didn’t argue! You’d have thought it was a bacchanalian romp, and it was only a beetle drive in the parish hall in aid of the church choir!’

‘They met at a beetle drive?’

‘No. They bumped into each other – literally – in the village in the blackout. People bumped into just about everything, come to think of it. Lampposts especially were the very devil. You could get a nasty bang from one of those, apart from breaking your glasses, if you wore them!

‘Anyway, this airman was full of apologies and insisted on walking us to the transport. The transport, I ask you! He thought we were going to the sergeants’ mess dance at the aerodrome! The RAF had a dance there every week, and they always sent a lorry round the villages, collecting girls. Lady partners were a bit thin on the ground, you see. Folk around these parts called it the love bus.

‘Of course, respectable girls weren’t allowed to go. No knowing the trouble they might get themselves into! Chance would’ve been a fine thing! I don’t know what got into the pair of us that night because we followed the airman and he helped us onto the transport. We were the only two from Acton Carey!’

‘And that’s where it all started – at a forbidden dance?’

‘That’s where. In a Nissen hut, actually. Not in the least romantic, but it was love at first sight for those two. I suppose you’d call it physical attraction nowadays!’

‘That was very daring of you,’ I teased. ‘I suppose you let him walk you both home!’

‘You bet we did! The blackout did have its uses, you know, and we both reckoned we might as well be hanged for sheep. I lived in one of the lodges at the Hall then, so it was a fair walk. We didn’t wait for the love bus because we had to be back before the beetle drive finished. Jack’s tail-end Charlie escorted me. Mick, his name was. Lovely dancer …’

‘Tail-end what?’

‘Charlie. There were two gunners to each bomber: one amidships, sort of, and another in the tail. Susan and I got to know them all. Mick and I started seeing each other, but we were more dancing partners than anything else. Not like Jack and Susan. Those two were smitten right from the start. He was gorgeous. Tall, fair-haired. Susan was fair too. A golden couple. I’d look at them together and think it was too good to last, and I was right!

‘But here’s me rabbiting on, and you wanting to look at the church!’ She ground her cigarette end into the grass, then brushed a hand across her skirt. ‘I’ll show you round if you’d like. We’d better get a move on. They’ll be finishing soon, and the church has to be locked. When I was young, churches were never locked and the altar silver out for all to see. Thieves left churches alone in those days …’

‘If there isn’t a lot of time left, then I’d rather see the original part of the building.’ I felt less breathless now. ‘It’s ages old, I believe.’

‘Built in the thirteenth century, when few could read or write but who believed implicitly in heaven and hell and eternal damnation! It’s the Lady Chapel now and so simple it’s beautiful. When it was built, so small a church wouldn’t have had pews and the faithful would have stood right through the service – all except the Lord of the Manor and his family, who’d have had special chairs. But let me show you …’

I didn’t go to the Red Rose when I left the church. My head was too full of Susan and Jack, and besides, Beth and Danny would be home the following day and I wanted to clean the house before I went to meet Jeannie’s train.

My word processor was already packed in its carrying box; no more Firedance until Monday; no more working at the kitchen table with Hector beside me and Tommy curled up in the armchair! Sadness took me just to think of leaving, so I thought instead of Mum and Dad and how pleased they would be to have me home again.

But it was difficult not to think of Susan and Jack and how glad I was to have found a lead in the very nick of time. I’d tried not to appear too interested for fear of arousing suspicion, because far too many people think that anything said to a novelist would appear, completely unashamed and unabridged, in her next book! I’d felt just a little guilty, especially when Mrs Taylor said, on parting, that I had only to write to her or phone if there was anything I wanted to know about the history of the area or about the war. I had her address and phone number in my purse, though at the back of my mind I knew it would be a long time before I would be in touch. Firedance must first be completed, and a lot could happen in the space of three and a bit novels – even supposing Harrier Books gave me that contract!

I was snipping red roses when the phone rang, and I ran to answer it.

‘Cassie! I’m at King’s Cross. Is the minicab available – same time?’

‘It is.’

‘Beth rang. Said they were taking it easy and would be home late on Saturday night about eight – give or take the odd traffic jam!’

‘She rang me too!’

‘Fine! See you, then!’

‘That was Jeannie,’ I said to Hector, who always came to investigate when the phone rang – just in case, I supposed, there was a man on the other end of it! ‘I’m going home soon. Are you going to miss me?’

He whined softly and looked at the biscuit tin, which was his way of telling me he would, and the custard creams too, and I felt a sudden ache inside me to think that soon he too would be leaving Deer’s Leap. Poor Hector, poor Cassie, poor Jack and Suzie!

‘Life’s a bitch,’ I said out loud. ‘And then you die!’

Even when you were hardly into manhood, I thought soberly, and you didn’t want to die and your girl didn’t want you to either!

Then I thought about Piers, whom I hadn’t really loved at all, and promptly burst into tears at the unfairness of it.

On the way back from Preston station, I slowed automatically as we neared the clump of oak trees and Jeannie slid me a warning glance

‘You’re at it again, Cassie! You’re still on the lookout for him! I thought you’d decided to let it drop.’

‘Yes, I had.’ I put my foot down, because there wasn’t a single vibe to be felt. ‘And I really meant it at the time, but something happened this morning.’

I told her about going to the church – hand-on-heart only to look at it! – and how I’d met Mrs Taylor who once was Susan’s closest friend, and there in Acton Carey all the time!

‘What do you mean – living in the village all along? Then why didn’t Bill Jarvis mention it? He knew we – you – were interested.’

‘Maybe it slipped his memory. It all happened a long time ago, and he was older than Susan, didn’t he say, and away in the army for a lot of the war. That could be why he wouldn’t know about the Smiths’ mysterious departure – without a goodbye to anyone. It was a shock to Lizzie. Even she hadn’t known when they were going.’

I told her all I’d learned, and said surely Bill would have told us about something that caused such a stir at the time, if he’d known about it.

‘Maybe he did. Maybe,’ she said over her shoulder as she got out of the car to open the white gate, ‘he was rationing his knowledge – with the beer in mind!’