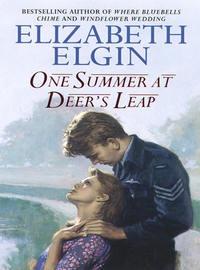

One Summer at Deer’s Leap

I read on, fascinated to learn that on 15 July 1944, RAF Acton Carey had been handed over to the United States Army Air Corps, who flew daylight missions from there until the end of hostilities in Europe – VE Day. Those huge American Flying Fortresses needed longer runways to take off and land, and what remained of Deer’s Leap fields had been absorbed into the airfield.

Yet now Deer’s Leap was once again a place of tranquillity. All that was left were memories, a war memorial in a quiet village – and the ghost of a pilot who waited for his girl; had been waiting for more than fifty years.

Near to tears, I closed the book with a snap. It was history now, I insisted; had ended when my mother was a baby. It was nothing at all to do with me, so why was I thinking about it every spare moment I had? Why did I feel the need to find Susan Smith?

I had no way of knowing. All I could be certain of was that Jack Hunter had latched on to me as his only hope, and I could not let him down.

‘I lit a fire last night,’ I said to Jeannie as I stowed her bags in the car boot. ‘The house seemed a little cold, after the rain. Shall we light one tomorrow night? I’ve got a bottle of wine – or would you like to go to the Rose again?’ I said off-handedly, though I was desperate to talk to Bill Jarvis.

‘Go on the bikes, you mean? I’d love to, Cassie.’

‘So would I, actually.’ The relief in my voice was obvious. ‘And we’d be better at it this time. Cycling uses up four calories a minute, did you know?’

‘Big deal,’ Jeannie grinned, because she ate whatever she fancied and didn’t put on an ounce.

‘Bill Jarvis might be there. I’d like to talk to him again.’

‘It’ll cost us, Cassie. Bill never does owt for nowt!’

‘It’ll be worth it. I want to talk to as many of the old ones as I can – get them to tell me how it was when they were young. Money well spent!’

I indicated right at the next set of lights, taking the Clitheroe road. Soon we would be driving through Acton Carey; passing a clump of oak trees and the spot at which I first met Jack Hunter. I wondered if I wanted him to be there tonight when Jeannie was with me, and decided I did not, because Jeannie might not even know he was there. Not everybody can see, or even sense ghosts.

The matter didn’t arise, though. We drove past the oaks and The Place without incident and when she got out to open the white gate for me, I had time to take a look at the kissing gate. He wasn’t there, either.

‘Thanks, chum,’ I whispered as Jeannie waved me through; thanks, I meant, to Jack Hunter for not being there. After all, he was taboo, wasn’t he?

Jeannie took her bags upstairs whilst I made a pot of tea.

‘It’s a lovely evening. Shall we put cardies on, and have it on the terrace?’

Jeannie said it was a good idea, and was there any parkin left?

‘We ate it all, but Mum and Dad might come up for the day, next week, and she’ll bring some with her. I particularly asked her to. I thought they might’ve come on Sunday, but Dad’s busy, judging at flower shows.’

We sat there without speaking because Jeannie had closed her eyes and was taking long, slow breaths.

‘Penny for them,’ I said when I’d had enough of the quiet.

‘I was just thinking that I could get out of publishing,’ she smiled, holding out her empty cup, ‘if I could find a way to bottle this air. People in London would pay the earth for it.’

‘Then before you do – give up publishing, I mean – I think I ought to tell you that I’m getting ideas about the next book.’

‘Good girl. That’s what I like. Unbridled enthusiasm. Got anything of a storyline worked out?’

‘We-e-ll, what would you say if I told you it would have Deer’s Leap in it, and the year would be 1944? Will war books be old hat by the time I get it written?’

‘Dunno. Depends on who’s writing them, and the genre. Would it be blood and guts, sort of, or a love story?’

‘A love story – and tragic.’

‘A World War Two Romeo and Juliet, you mean?’

‘Mm. I was talking to Bill on Wednesday night. He told me there had been a lot of crashes hereabouts and that Acton Carey wasn’t a very safe place to be.’

‘And you feel strongly enough about that period to write about it with authority? There are a lot of people alive still who would soon let you know if you got anything wrong.’

‘I’ll tell you something, then.’ It was my turn to take a long, deep breath. ‘When I was at the library I saw a book about all the Bomber Command airfields in Lancashire during the war and bombing raids flown from Acton Carey are all listed in it. Someone went to a lot of trouble to get all the details. The Lancasters must have gone somewhere else, because in July 1944 the American Army Air Corps took the place over.’

‘I wonder where those squadrons of Lancasters went.’ Jeannie was getting interested.

‘I don’t know. But I did see the war memorial in the village. Remember Danny said the names of a crew that crashed hereabouts were included with the local dead?’

‘Yes. But I wonder why one particular crew, when there must have been a lot of crashes …’

Jeannie was interested, all right. It gave me the courage to jump in feet first and say, ‘I can’t tell you that, but I’m going – just this once – to talk about someone we agreed not to talk about again.’

‘Your ghost? I knew we’d get round to him sooner or later!’

‘His name was Jack Hunter,’ I rushed on. ‘There’s a J. J. Hunter on that memorial and the date is 8 June. It was one of the last raids flown before the Royal Air Force left Acton Carey. In the book it says it was a daylight raid on a flying bomb site in France.’

‘So why can’t he accept it? Doesn’t he know he’s on a war memorial?’

‘I don’t think he’s grasped the fact yet that he’s dead. I think,’ I said, not daring to look her in the face because I didn’t think, I knew, ‘that the girl who lived here and the pilot were – well, an item.’

‘And you want to write about them, even though you know he was killed?’

‘I’d use different names. No one would know.’

‘Except the girl who once lived here if she’s still alive. It’s just the kind of book she’d be interested in, she having had first-hand experience, kind of.’

‘I said I’d disguise it. There is a story there, and I’d handle it very gently, Jeannie.’

‘Yes, I do believe you would. You aren’t a little in love with that pilot, are you?’

‘Don’t be an idiot! Why would I want to fall in love with a ghost? Be a bit frustrating, to say the least!’

‘From what you’ve said, he seems the exact opposite of your Piers.’

‘He isn’t my Piers. I’ll admit we had something going once, but it’s wearing a bit thin – on my part, that is. But I don’t find Jack Hunter attractive!’ I crossed my fingers as I said it.

I lay in bed with the windows wide open, listening to the strange, waiting stillness outside; mulling over what we had talked about. And I thought about Jack Hunter too, and his slimness and the height of him and that I had found him attractive. Maybe that was why I wasn’t in the least afraid of him – or what he was. Excited, maybe, when he was around, but no way did he frighten me. That pilot was exactly my type. I’d already decided, hadn’t I, that if I’d been around these parts fifty-odd years ago, I’d have given Susan Smith a run for her money?

Jack Hunter danced perfectly, I knew it, and I felt an ache of regret that I would never dance closely with him. Then I felt relief that every time we kissed I would never know the fear it might be our last.

‘Stupid!’ I hissed into the pillow. Not only did I see ghosts, but I’d fallen in love with one!

I plumped my pillow and turned it over. I wasn’t in love with the man! I only wanted to be, with someone very like him; someone who was flesh and blood and whose kisses were real!

‘Deer’s Leap,’ I whispered indulgently, ‘what have you done to me …?’

Chapter Six

I awoke early in need of a mug of tea, after which I would throw open all the downstairs windows and doors – get a draught through the house.

August mornings should be fresh, not oppressive. I looked towards the hills as I let Hector out. Clouds hung low over the fells and there was little blue sky to be seen.

I put down milk for the cats and the clink of the saucers soon had them crossing the yard in my direction. Tommy had not slept on my bed last night, but then cats are known to find the warmest – or the coolest – places and he’d probably slept outside.

I drank my tea pensively, trying to push the words out of my mind that were already crowding there. Today and tomorrow were holidays – even if the weather seemed intent on spoiling them.

Did bad weather stop aircraft taking off and landing during the war? I frowned. Fog certainly was bad – it could still disrupt an airport – but how about snow on runways, and ice? Perhaps conditions like that gave aircrews a break from flying; a chance to go to the nearest pub or picture house. Or scan the talent at some dancehall, looking for a partner who might even be willing to slip outside into the blackout. Did they snog, in those days, or did they pet, or neck? Things – words, even – had changed over the years. Words! My head was full of them again; words to find their way into the next book, even though I was barely halfway through the current one!

I showered and dressed quickly and quietly, then told Hector to stay. I was going to the end of the dirt road to leave money for the milkman.

‘Good boy.’ I gave him a pat, and some biscuits, then shut the kitchen door. If Jack Hunter was at the kissing gate, I didn’t want trouble, even though dogs are supposed to be frightened of ghosts. Cats, too.

As I closed the white gate behind me, it was evident that no one was there. The kissing gate was newly painted in shiny black. Perversely, I touched it with a forefinger and it swung open easily.

There were letters in the wooden box, mostly bills or circulars. Only one, a postcard view of Newquay, was addressed to me.

Having a good time. Weather variable. Hope all is well. D. & B.

I glanced up at the sky. The weather was variable in the Trough of Bowland too. What was more, I’d take bets that before the day was out we would have thunder.

When I got back, Tommy was waiting on the step, purring loudly. I could hear Hector barking and hurried to tell him to be quiet before he woke Jeannie.

I stood, arms folded, staring out of the window. If a prospective buyer looked at Deer’s Leap on a day such as this, I thought slyly, one of its best assets – the unbelievable, endless view – would be lost. I supposed too that the same would apply if they came in winter, when the snow was deep. The view then would be breathtaking – if they managed to make it to the house, of course. Still, even if we had a storm today it wouldn’t be the end of the world. My troubles were as nothing compared to those of Jack and Suzie.

Hector whined, rubbing against me. Lotus was nowhere to be seen, but Tommy prowled restlessly, knowing a storm threatened.

I piled dishes in the sink, then set the table for Jeannie. Like as not she would only want coffee – several cups of it – but laying knives and forks and plates and cups gave me something to do.

Even the birds were silent. A few fields away, black and white cows were lying down. They always did that when rain threatened, so they could at least have a dry space beneath them when the heavens opened. Clever cows!

I turned to see Jeannie standing there, yawning.

‘Hi!’ I smiled. ‘Sleep well?’

‘Hi, yourself.’ She pulled out a chair, then sat, chin on hands, at the table. ‘I woke twice in the night; it was so hot. I opened windows and threw off the quilt then managed to sleep, eventually.’

‘Coffee?’

‘Please. Why is everything so still?’

‘The calm,’ I said, ‘before the storm. We’ll have one before so very much longer. Are you afraid of thunder, Jeannie?’

‘No. Are you?’

I shook my head. ‘Want instant, or a ten-minute wait?’ I grinned.

‘Instant, please.’ She yawned again. ‘You’re a busy little bee, aren’t you? How long have you been up?’

‘Since seven. I’ll just see to your coffee, then I’ll nip down to the lane end and collect the milk before it rains.’

All at once, I wondered how it would be when it snowed. It took me one second to decide that if I lived here I wouldn’t care.

‘We won’t go down to the Rose if the weather breaks, will we?’

‘No point,’ I shrugged. ‘There’s lager and white wine in the fridge. We can loll about all day and be thoroughly lazy.’

‘I’m glad I came, Cassie,’ she smiled.

‘I’m glad you did,’ I said from the open doorway. ‘Won’t be long.’

I didn’t expect anyone to be at the iron gate, or even walking up the dirt road, and I wasn’t disappointed. Ghosts, I reasoned, were probably the same as cats and dogs and didn’t like thunderstorms.

I put a loaf and two bottles of milk into the plastic bag I had learned to take with me, and set off back. It could rain all it liked now.

I wondered if there were candles in the house in case the electricity went off like it sometimes did at home when there was a storm.

I made another mental note to ring Mum tomorrow from the village, then sighed and quickened my step, glad that for two days I had little to do but be lazy.

Jeannie crossed the yard from the outhouse where Beth kept two freezers.

‘I think we might have chicken and ham pie, chips and peas tonight. And for pudding –’

‘No pudding,’ I said severely. ‘Not after chips! And is it right to eat Beth’s food?’

‘Beth told us to help ourselves – you know she did.’

‘OK, then.’ I decided to replace the pie next time I went to the village. ‘And are there any candles – just in case?’

‘No, but Beth has paraffin lamps. Everybody keeps them around here. Are you expecting a power cut?’

‘You never know. It could happen if we get a storm.’

‘Then thank goodness the stove runs on bottled gas! At least we’ll be able to eat!’

‘Do you think of anything but food? No man in your life, Jeannie?’

I had stepped over the unmarked line in our editor/author relationship, and it wasn’t on. Immediately I wished this personal question unasked. I put the blame on the oppressive weather.

‘Not any longer. I found out he was married – living apart from his wife.’

‘No chance of a divorce?’

‘His wife is devoutly Catholic, he said.’

‘He should have told you!’

‘Mm. Pity I had to find out for myself,’ she shrugged. ‘Still, it’s water under the bridge now.’

She said it with a brisk finality and I knew I had been warned never to speak of it again. So instead of saying I was sorry and she was well rid of him, I had the sense, for once, to say no more.

The storm broke in the afternoon. We sat in the conservatory, watching it gather. The air was still hot, but Parlick Pike and Beacon Fell were visible again, standing out darkly against a yellow sky.

‘This conservatory should never have been allowed on a house this old,’ Jeannie said, ‘but you get a marvellous view from it for all that.’ It was as if we had front seats at a fireworks display about to start.

‘Are the cats all right?’

‘They’ll go into the airing cupboard – I left the door open. Hector will be OK, as long as he stays here with us.’ She pointed in the direction of Fair Snape. ‘That was lightning! Did you see it?’

I had, and felt childishly pleased it was starting. I quite liked a thunder storm, provided I wasn’t out in it.

It came towards us. Over the vastness of the view we were able to watch its progress as it grew in ferocity.

‘You count the seconds between the flash and the crash,’ I said. ‘That’s how you can calculate how far away the eye of the storm is.’

We counted. Three miles, two miles, then there was a vivid, vicious fork of lightning with no time to count. The crash seemed to fill the house.

‘It’s right overhead,’ Jeannie whispered.

That was when the rain started, stair-rodding down like an avalanche. It hit the glass roof with such a noise that we looked up, startled.

‘Times like this,’ Jeannie grinned, ‘is when you know if the roof is secure.’

I knew that old roof would be; that Deer’s Leap tiles would sit snug and tight above.

The storm passed over us and I calculated they would be getting the worst of it in Acton Carey. Lightning still forked and flickered, but we were becoming blasé after the shock of that one awful blast.

‘I wonder if it was like this in the blitz – the bombing, you know.’

‘Far worse, I should imagine. Bombs killed people. Are we back to your war again, Cassie?’

‘It isn’t my war, but there’s something I’ve got to tell you.’

Even as I spoke, I knew I was being all kinds of a fool, so I blamed the storm again.

‘About …?’

‘About what we agreed not to talk about. Shall I make us a cup of tea?’

I was glad to retreat into the kitchen, to get my thoughts into some kind of order, relieved to find the storm had not affected the electric kettle. When I carried the tray into the conservatory, Jeannie was standing at the door, gazing out.

‘You think you’ve seen the ghost again – is that it?’ she said, her back still to me.

‘I’ve seen him. Twice more. Come and sit down.’ I made a great fuss of stirring the tea in the pot, pouring it.

‘Right then!’ She placed her cup on the wicker table at her side, then selected three biscuits, still without looking at me. ‘And I don’t for the life of me know why I’m so silly as to listen to you,’ she flung, tight-lipped. ‘You’re normally such a down-to-earth person!’

‘I know what I saw and heard,’ I said stubbornly. ‘Do you want to hear, or don’t you?’ I took a gulp of my tea. ‘Well – do you?’

‘There’ll be no peace, I suppose, till you’ve told me.’

There came another startling flash of lightning, followed almost at once by a loud peal of thunder. The storm we thought was passing had turned round on itself as if it were searching for a way out of the encircling hills.

‘I’m getting bored with this!’ Jeannie lifted her eyes to the glass roof. The rain was still falling heavily and making a dreadful noise above us. ‘Let’s go into the kitchen.’ She picked up the tray and I followed her, carrying the plate of biscuits. Hector slunk behind me, whining, so I gave him a pat and a custard cream.

‘Now.’ Jeannie settled herself at the table, back to the window. ‘You are serious? After all we agreed, you’ve been poking about again!’

‘I have not! I went to the Rose on Wednesday night, and I’ll admit asking Bill about the people who once lived here. It was natural that since the RAF was the cause of them getting thrown out, we should talk about the Smiths.’

‘And …?’

‘Look, Jeannie – I didn’t tell you, but I saw the pilot at the kissing gate, last Saturday morning! One second he was there; the next he’d gone!’

‘When you’d been to the post office, you mean?’

‘Yes. You said I was acting a bit vague; asked me if I had a headache.’

‘So I did,’ she said softly, ‘yet you said nothing!’

‘I only saw him out of the corner of my eye, but that gate opened of its own accord and I heard it squeak. He was there!’

‘That gate doesn’t squeak, Cassie!’

‘It did during the war, and was rusty and in need of painting!’

‘So when did he appear again?’ She licked the end of her forefinger, picking up biscuit crumbs with it from her plate. She was doing it, I knew, to annoy me.

‘Last Wednesday night.’ I took a deep breath, and she lifted her head and looked at me at last. ‘I’d been to the Rose, talking to Bill. I took the car, so I hadn’t been drinking! I saw him clearly, ahead of me, near the clump of oak trees. It was bright moonlight, Jeannie. I could’ve put my foot down, like it seems people around these parts do if they think it’s him. But I didn’t. I stopped. He seemed anxious to get to Deer’s Leap.’

‘Like last time?’

‘Yes. Just like last time. He wanted to let Susan Smith know he was on standby. And before you ask,’ I rushed on, ‘standby means they might be flying on a bombing mission. I asked him. Then he said he wanted to tell Susan he maybe couldn’t make it that night. Seems he was hoping to meet her parents for the first time.’

‘And it was important?’

‘Seemed so to me. They wanted to get married, you see.’

‘No, I don’t see. He’d never met her folks, yet they were planning to get married? Is that likely?’

‘Bill Jarvis said parents didn’t like their daughters dating aircrew because so many of them got killed. Jack and Susan managed to meet secretly.’

‘And the pilot told you all that – opened up his heart to you about Susan?’

‘Why shouldn’t he? Seems I’m the first person in more than fifty years to take any notice of him. And he called her Suzie, not Susan.’

‘Well, all I can say is that either you’ve got one heck of an imagination, or you really do think you’ve seen him again!’

‘I have! And talked to him. And don’t try to tell me he doesn’t exist. He’s real enough for Beth and Danny to more or less warn me off!’

‘But, Cassie – he might be something someone hereabouts invented.’

‘So who told me then? Bill didn’t say one word about him to me.’

‘Well, he wouldn’t. Nobody round Acton Carey talks about him! Like Beth said, they don’t want the press in on it.’

‘But if Jack Hunter doesn’t exist, why try to cover him up? Why not let the reporters run riot – make fools of themselves?’

‘OK, Cas!’ She threw up her hands in mock surrender. ‘So there have been rumours from time to time about – something …’

‘Too right there have! Beth has seen him. She as good as admitted it.’

‘But doesn’t he scare you?’

‘No. He doesn’t groan or rattle chains. You could take him for a real person, except he seems able to vanish into thin air like he did on Wednesday.’

‘Where did he seem to vanish to?’

‘I don’t know, exactly. I got out of the car to open the big gate and when I got back, he’d gone. All I knew was that I heard the kissing gate creak.’

‘The one that needs painting?’

‘You don’t believe me, do you?’ I was getting annoyed. How could she be so stubborn?

‘I – I, oh, I don’t know what to believe. And why does the kissing gate feature so strongly in it, will you tell me?’

‘Because to my way of thinking, Susan Smith used to sneak out and meet him there. They’d be safe enough; the blackout would hide them.’

‘Except on moonlit nights and in summer, when it was supposed to be light until eleven at night,’ she shrugged, determined to play devil’s advocate.

‘When people are in love and they know they might not have a lot of time, they find a way. I would’ve.’

‘All right. Point taken! So tell me – what is he like, your airman?’

‘He’s tall and slim – thin, almost. He’s got fair hair and it’s cut short at the sides. I suppose what they’d call a regulation cut. But it’s thick on top, and a bit flops over his right eye. He has a habit of pushing it aside.’

‘So what are you going to do, Cassie – about the airman, I mean?’

‘I don’t know. I want to help, because he’s looking for his girl and there’ll be no peace for him until he finds her – or more to the point, until she finds him. I reckon, you see, that he’s rooted to what was once an airfield.’

‘Trapped in a time warp, you mean?’

‘Exactly. Look, Jeannie – are you with me or are you against me? I’d like to know.’

‘Why? So I can help you?’

‘No. It’s me Jack Hunter is interested in. Seems I must be a bit of a medium and he’s latched on to it. So it’s all going to be up to me. But you can help by believing that I’m not going out of my tiny mind.’