The Cruel Victory: The French Resistance, D-Day and the Battle for the Vercors 1944

‘They’re coming!’ someone shouted.

1

THE VERCORS BEFORE THE VERCORS

For those who live around the Vercors massif – from the ancient city of Grenoble lying close beneath its north-eastern point to the vineyards of Valence scattered around its south-western slopes – the forbidding cliffs of the plateau are the ramparts of another country. To them, this is not just a mountain. It is also a state of mind. Even when hidden behind a curtain of summer rain or with its summits covered by the swirling clouds of a winter tempest, the great plateau is still there – offering something different from the drudgery and oppressions of ordinary life down below. Best of all, on still, deep-winter days, when the cold drags the clouds down to the valleys, up there on the Vercors looking down on the sea of cloud, all is brilliant sunshine, deep-blue skies, virgin snow and a horizon crowded with the shimmering peaks of the Alps.

Today, this is a place of summer escape and winter exhilaration. But its older reputation was as a place of hard living and of refuge from retribution and repression.

The historical importance of the Vercors lies in its strategic position dominating the two major transport corridors of this part of France: the Route Napoleon which passes almost in the shadow of the plateau’s eastern wall and the valley of the River Rhône, which flows through Valence some 15 kilometres away from its south-western shoulder.

The Romans came this way fifty years before the birth of Christ. Pliny, writing in AD 50, referred to the people of the plateau as the Vertacomacori, a word whose first syllable may have been carried forward into the name ‘Vercors’ itself. Eight centuries later, the Saracens followed the Romans, implanting themselves in Grenoble for some years. According to local legend, they even sent a raiding party towards the Pas de la Balme on the eastern wall of the plateau, but were beaten back by local inhabitants rolling rocks down on the invaders. Less than a hundred years later, towards the end of the tenth century, the Vikings came here too, but from the opposite direction – south down the Rhône in their longships. And 400 years after that, the Burgundian armies followed them on their own campaign of conquest and pillage. Then in March 1815, Napoleon, after landing on the Mediterranean coast from Elba, marched his growing army north along the route which still bears his name under the eastern flank of the Vercors, towards Grenoble, Paris and his nemesis at Waterloo.

Napoleon excepted, what is most significant about these invaders is that, though there are signs enough of their passing in the countryside below, there are few on the Vercors itself. It is as though these foreigners were content to pass by in the valleys without wishing to pay much attention to the cold, poverty-stricken and inhospitable land towering above them. One consequence of this passage of armies and occupiers is, however, more permanent. The historian Jules Michelet, writing in 1861, commented: ‘There is a vigorous spirit of resistance which marks these provinces. This can be awkward from time to time; but it is our defence against foreigners.’

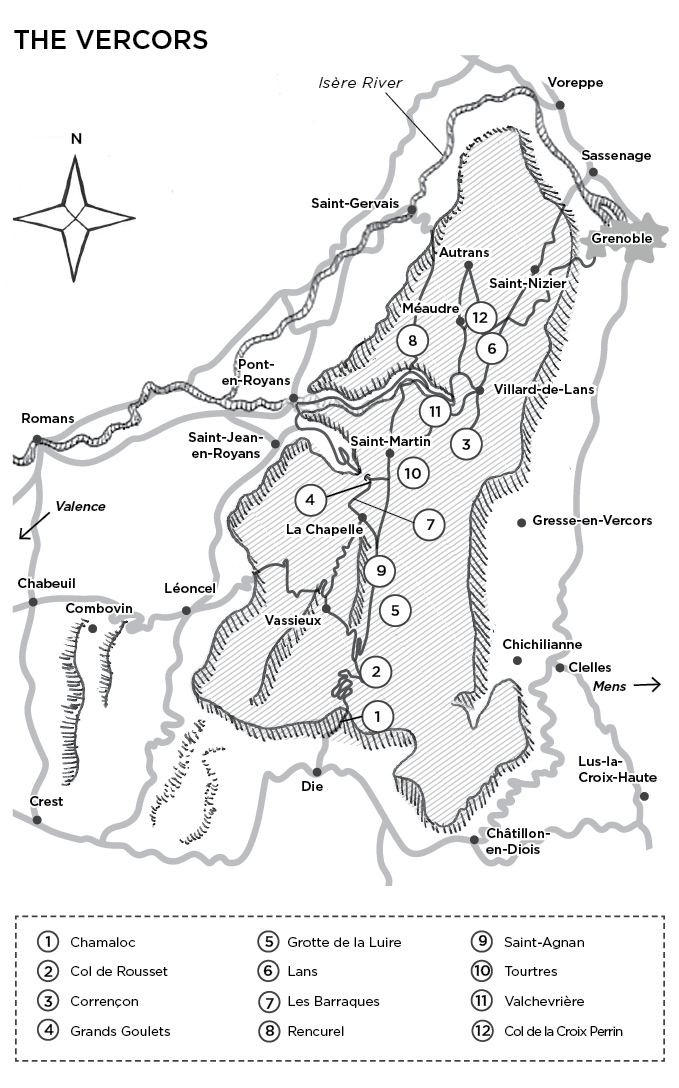

The plateau itself is shaped like a huge north-pointing arrowhead some 50 kilometres long and 20 wide. It covers, in all, 400,000 hectares, about the same size as the Isle of Wight. An Englishman who will play a small part in this history described it, in his prosaic Anglo-Saxon way, as a great aircraft-carrier steaming north from the middle of France towards the English Channel.

This extraordinary geological feature is the product of the the shrinking earth and the faraway press of the African continent, whose northward push against the European mainland generates the colossal pressures which wrinkle up the Alps and squeeze the Vercors limestone massif straight up in vertical cliffs, 1,000 metres above the surrounding plain.

Map 1

No concessions are found here to accommodate the needs of man. The Vercors offers nothing in the way of easy living. Extreme difficulty of access made the plateau one of the poorest areas, not just of France, but of all Europe, until new roads were blasted up the cliff faces in the nineteenth century. The forbidding bastion of the eastern wall of the plateau, stretching from Grenoble to the plateau’s southern extremity, is accessible only by goats, sheep and intrepid walkers. For vehicles, there are just eight points of access to the plateau, one on its southern flank, five spread out along its western wall and two on its north-eastern quarter. Of these, all bar one involve either deep gorges into which the sun hardly ever penetrates or roads which rise dizzily through a tracery of hairpin bends to run along narrow ledges and through dark tunnels blasted from vertical rock faces.

Only the road on the plateau’s north-eastern edge offers something different. Here the slope rises placidly from the back gardens of the Grenoble suburbs and is served by a moderately engineered road, supplemented, until 1951, by a small funicular tramway, at the top of which is the little town of Saint-Nizier. This sits on its own natural viewing platform, looking out over the city to the mountain-flanked valley of the Isère (known as the Grésivaudan valley) and the white mass of Mont Blanc in the distance.

The Vercors plateau itself is dominated by three rolling ridges which run along its length from north to south like ocean breakers. Their tops are above the treeline, rock-strewn and so sparsely covered with mountain grasses that on bright summer days the white from the limestone below seems to shimmer through the thin air and dazzle the eyes. In some high, very exposed areas, where the hot summer winds have whipped off all the soil, the limestone rock is laid bare and fissured into deep cracks, some large enough for a man – or several men – to stand up in. These are wild and terrible places, known to the locals as lapiaz. Their only gentleness lies in the strange lichens and alpine plants which make their homes in the cracks and survive by straining moisture from the dew-laden air of summer mornings.

Further down, there are cool conifers and one of the largest stands of hardwood in western Europe. Further down still, cradled in the valleys, are the little towns, villages and hamlets of the Vercors community – many of them, such as Saint-Martin, Saint-Julien, Saint-Agnan, La Chapelle, speaking of a past where an attachment to the right God was as important to survival as skill at animal husbandry and knowing the right time to plant the crops. Here, though the bitter snow-filled winters remain tough, there is good grazing and comfortable summer living.

One essential ingredient of life, however, is not easily available – water. This is a limestone plateau and every drop that falls as rain or seeps away from melting snow drops down through the limestone into hidden channels, underground rivers and a still-undiscovered network of chambers and caverns which honeycomb the whole Vercors plateau. Some say a drop of moisture captured in a snowflake which falls on the summit of the plateau’s highest peak, the 2,341-metre Grand Veymont, will take three years to pass in darkness through the hidden channels under the mountains before it sees the light of day again, tumbling down through the plateau’s gorges on its way to the Rhône and the warm waters of the Mediterranean far away to the south. Surface water across the whole plateau is rare and wells and springs even more so. All of them are widely known and meticulously marked on every Vercors map.

This is the unique topography and meteorology which has played such an important part in shaping both the Vercors, and the lives of those who have struggled to live and take refuge there, not least during the years of France’s agony in the Second World War.

But it is not just the topography that makes the Vercors unique. The plateau lies at the precise administrative, architectural, cultural and meteorological dividing line between northern, temperate, Atlantic France and that part of France – Provence – which looks south to the Mediterranean. The frontier between the departments of the Isère and of the Drôme divides the plateau into two halves: the northern Vercors is in the Isère and the southern Vercors is in the Drôme.

At least until the Second World War, these two Vercors were quite different. Indeed, as late as the nineteenth century, the rural folk of the plateau spoke two different and mutually incomprehensible languages, the langue d’oc and the langue d’oïl. The northern Vercors took its lead from sophisticated Grenoble. Here, at Villard-de-Lans, was established one of the first – and one of the most fashionable – Alpine resorts in France, frequented in the 1930s by film stars, the fashionable, the sportif and the nouveau glitterati of Paris. During pre-war summers, the area became one of the favourite Alpine playgrounds for those with a passion for healthy and sporty living; it teemed with hikers, climbers, bikers and even practitioners of Robert Baden-Powell’s new invention from England, le scouting. The southern Vercors on the other hand – the ‘true Vercors’ according to its inhabitants – remained virtually unchanged: still agricultural, still largely isolated, still taking its lead more from Provence and the south than the styles and sophistications of Paris and the north.

This division is visible even in the vegetation and architecture of the two halves. Travel just a few tens of metres south through the short tunnel at the Col de Menée at the south-eastern edge of the plateau and there is a different feel to almost everything. Even the intensity of the light seems to change. Pine trees, temperate plants and solid thick-walled houses, whose roofs are steeply inclined for snow, give way almost immediately to single-storey houses with red-tiled roofs crouching against the summer heat, tall cypresses as elegant as pheasant feathers, the murmuring of bees and the scent of resin in the air. Here the hillsides are covered with wild thyme, sage and the low ubiquitous scrub called maquis, from which the French Resistance movement took its name.

Many factors and many personalities shaped the events which took place on the Vercors during the Second World War. One of them was the extraordinary, secluded, rugged, almost mythical nature of the plateau itself.

2

FRANCE FROM THE FALL TO 1943: SETTING THE SCENE

It is only the French themselves who understand fully the depth of the wounds inflicted by the fall of France in 1940. They had invested more in their Army than any other European nation with the exception of Germany. With around 500,000 regular soldiers, backed by 5 million trained reservists and supported by a fleet of modern tanks which some believed better than the German Panzers, the French Army was regarded – and not just by the French – as the best in the world.

It took the Germans just six weeks to shatter this illusion and force a surrender whose humiliation was the more excruciating because Hitler insisted that it took place in the very railway carriage where Germany had been brought to her knees in 1918. It is not the purpose of this book to delve in detail into how France fell. But one important element of those six weeks in the summer of 1940 is often overlooked. Not all of France’s armies were defeated.

The French Army of the Alps – the Armée des Alpes – never lost a battle. They held the high Alpine passes against a numerically superior Italian assault. And they stopped the German Army too, at the Battle of Voreppe, named for the little town just outside Grenoble which guards the narrows between the Vercors and the Chartreuse massifs. Indeed the Battle of Voreppe ended only when the French artillery, wreaking havoc on German tanks from positions on the northern tip of the Vercors plateau, were ordered to return to barracks because the ceasefire was about to come into force. Thanks to this action, Grenoble and the Vercors remained in French hands when the guns fell silent. But this was small comfort to the victorious French Alpine troops who now found that they were part of a humiliated army. They regarded themselves as undefeated by the Germans but betrayed by the Armistice and ached to recover their lost honour.

The French rout and the German columns pushing deeper and deeper into France set in train a flood of internal refugees who fled south in search of safety. It was estimated that some 8 to 9 million civilians – about a quarter of the French population – threw themselves on to the roads, seeking to escape the occupation. They were later referred to as les exodiens. Among them were 2 million Parisians, French families driven out of Alsace-Lorraine and many Belgians, Dutch and Poles who had made their homes in France.

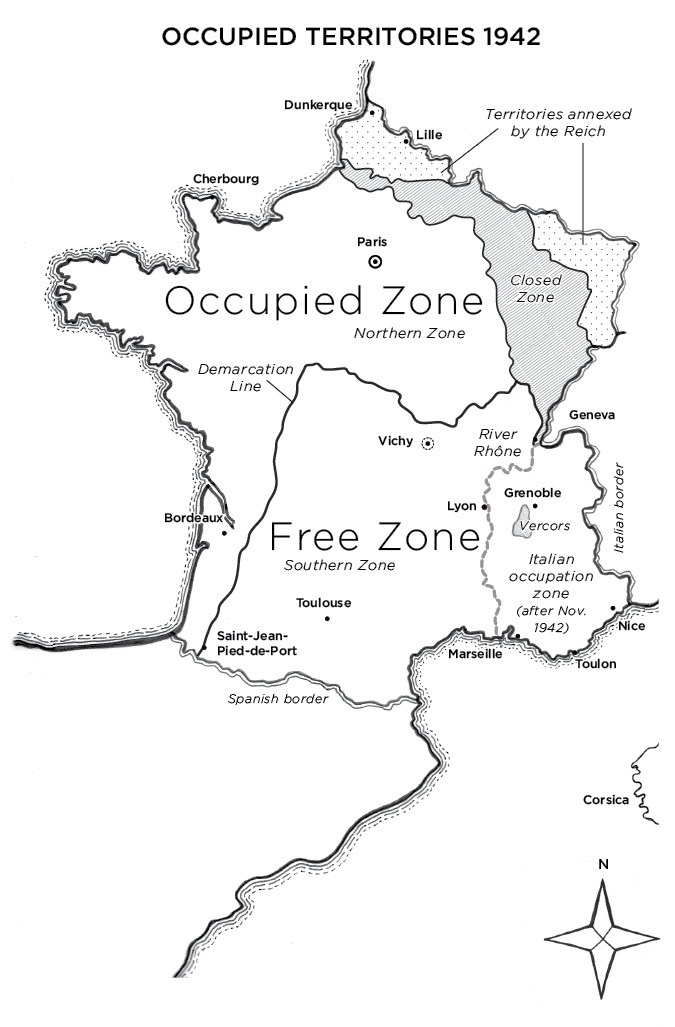

The ceasefire between German and French troops came into force at 09.00 on 24 June 1940 and was followed by the Armistice a day later. Under the terms of this peace, France was divided in two. The northern half, known as the Zone Occupée or ZO, was placed under General Otto von Stülpnagel, named by Hitler as the German Military Governor of France. The southern half, the Zone Non-Occupée or ZNO, comprising about two-fifths of the original territory of metropolitan France, was to be governed by Marshal Pétain, who set up his administration in the central French town of Vichy. The two were separated by a Demarcation Line, virtually an internal frontier, which ran from the border with Switzerland close to Geneva to a point on the Spanish border close to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.

Map 2

There was another France created by the nation’s defeat and humiliation, but very few knew about it at the time. It had left with General Charles de Gaulle in a British plane from Mérignac airport outside Bordeaux not long before the Armistice was signed. On 18 June 1940, just two days after he arrived in London, de Gaulle made the first of his famous broadcasts to the French people: ‘has the last word been said? … Is defeat final? No! Believe me, I who am speaking to you from experience … and who tell you that nothing is lost for France … For France is not alone! She is not alone! She is not alone! … This war is a world war. Whatever happens, the flame of the French resistance must not be extinguished and will not be extinguished.’ The sentences were stirring enough. The problem was, almost no one in France heard them. In the early 1940s there were only 6 million radios in France and, since a quarter of France’s population were in captivity, or fighting, or on the roads fleeing the invader, there were not many who had the time to sit at home with their ears glued to the radio, even if they had one.

With almost 70,000 casualties, 1.8 million of her young men in German prisoner-of-war camps and la gloire française ground into the dust alongside the ancient standards of her army, France’s first reaction to her new conqueror was stunned acquiescence. Early reports arriving in London from French and British agents all speak of the feeble spirit of resistance in the country. In these first days, many, if not most, of the French men and women who had heard of de Gaulle saw him as a rebel against the legitimate and constitutional government in Vichy. They trusted Pétain to embody the true spirit of France and prepare for the day when they could again reclaim their country. After all, was he not the hero of Verdun, the great battle of 1916? Some believed fervently that the old warrior’s Vichy government would become, not just the instrument for the rebuilding of national pride, but also the base for the fight back against the German occupier and that he, Pétain, the first hero of France, would become also the ‘premier résistant de la France’.

There were, of course, some who wanted France to follow Germany and become a fascist state. In due course they would be mobilized and turn their weapons on their fellow countrymen. But these were a minority. For the most part, after the turbulence and the humiliation, the majority just wanted to return to a quiet life, albeit one underpinned by a kind of muscular apathy. The writer Jean Bruller, who was himself a Resistance fighter and used ‘Vercors’ as his nom de plume, clandestinely published his novel Le Silence de la Mer in 1942. In this he has one of his characters say of France’s new German masters: ‘These men are going to disappear under the weight of our disdain and we will not even trouble ourselves to rejoice when they are dead.’

There were many reasons why, in due course and slowly, the men and women of occupied France broke free of this torpor and began to rise again. But two were pre-eminent: the burning desire to drive out the hated invader, and the almost equally strong need to expiate the shame of 1940 and ensure that the France of the future would be different from the one that had fallen.

The formation of the earliest Resistance groups came organically – and spontaneously – from French civil society. Some were little more than clubs of friends who came together to express their patriotism and opposition to the occupier. Others were political – with the Communists being especially active after Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s invasion of Russia in June 1941. Almost all were strenuously republican in their beliefs. There were even Resistance organizations supporting the regime in Vichy, preparing for the day when they would help to recapture the Zone Occupée. Although the early Resistance groups concentrated mainly on propaganda through the distribution of underground newspapers, over time they evolved into clandestine action-based organizations capable of gathering intelligence, conducting sabotage raids and carrying out attacks on German units and installations.

In London, too, France’s fall changed the nature of the war that Britain now had to fight. Now she was utterly alone in Europe. Churchill knew that, with the British Army recovering after the ‘great deliverance’ of Dunkirk, the RAF not yet strong enough for meaningful offensives against German cities and the Royal Navy struggling to keep the Atlantic lifeline open, the only way he could carry the war to the enemy was by clandestine rather than conventional means.

On 22 July 1940, he created the Special Operations Executive (SOE), instructing it to ‘set Europe ablaze’. SOE, headed by Brigadier Colin Gubbins and headquartered in Baker Street near Marylebone station, was organized into ‘country sections’ which were responsible for intelligence, subversion and sabotage in each of Europe’s occupied nations. France, however, had two country sections: F (for France) Section and RF (for République Française) Section. The former, led by Colonel Maurice Buckmaster, was predominantly British run and was staffed mostly by British officers and agents. The latter, which acted as a logistical organization for Free French agents sent into France, was made up almost exclusively of French citizens. Although members of the same overall body, SOE’s F and RF sections adopted totally different ways of doing business. The ‘British’ F Section operated through small autonomous cells, which were in most cases kept carefully separate from each other in order to limit the damage of penetration and betrayal. RF Section, on the other hand, tended to run much larger, centrally controlled agent networks.

But the organizational complexity and rivalry in London – which often seemed to mirror that on the ground in France – did not end there. De Gaulle, whose headquarters were at 4 Carlton Terrace overlooking the Mall, had his own clandestine organization too, headed by the thirty-one-year-old, French career soldier Colonel André Dewavrin. This acted as the central directing authority for all those clandestine organizations in France which accepted the leadership of Charles de Gaulle. However, as one respected French commentator put it after the war, ‘General de Gaulle and most of those who controlled military affairs in Free France in the early days were ill-prepared to understand the specificities of clandestine warfare … [there was a certain] refusal of career military officers to accept the methods of [what they regarded as] a “dirty war”. It was a long and difficult process to get [the French in] London to understand the necessities of the “revolutionary war”.’

For Churchill, who knew that a frontal assault on Festung Europa (Fortress Europe) was still years away, the strategic opportunities offered by the French Resistance, fractured and diffuse as it was, were much less appealing than those in the Balkan countries. The French Resistance may have been a low priority for Winston Churchill in these early years, but for General de Gaulle, who created the Forces Françaises Libres on 1 July 1940, it was the only means of establishing himself as the legitimate leader of occupied France. For him it was imperative to weld all this disparate activity into a unified force under his leadership, capable not only of effective opposition to the Germans, but also of becoming a base for political power in the future.

De Gaulle’s opportunity to achieve this came in October 1941 when the charismatic forty-one-year-old Jean Moulin escaped from France over the Pyrenees and arrived in Lisbon. Here Moulin, who, as the Préfet of the Department of Eure-et-Loire had been an early resister against the Germans, wrote a report for London: ‘It would be mad and criminal not to use, in the event of allied action on the mainland, those troops prepared for the greatest sacrifice who are today scattered and anarchic, but tomorrow could be able to constitute a coherent army … [troops] already in place, who know the terrain, have chosen their enemy and determined their objectives.’

Moulin met de Gaulle in London on 25 October 1941. The French General could be prickly and difficult, but on this occasion the two men instantly took to each other. On the night of 1/2 January 1942, Jean Moulin, now equipped with the multiple aliases of Max, Rex and Régis, parachuted back into France as de Gaulle’s personal representative. His task was to unify the disparate organizations of the Resistance under de Gaulle’s leadership. Thanks to Moulin’s formidable energy, organizational ability and political skill, he managed to unify the three key civilian Resistance movements of the southern zone into a single body whose paramilitary branch would become the Secret Army, or Armée Secrète, the military arm of the Gaullist organization in France.

Among those with whom Moulin made contact on this visit was the sixty-one-year-old French General, Charles Delestraint, who de Gaulle hoped would lead the Secret Army. On the night of 13/14 February 1943, a Lysander light aircraft of the RAF’s 161 Special Duties Squadron, which throughout the war ran a regular clandestine service getting agents into and out of France, flew from Tempsford airport north of London to pick up Moulin and Delestraint and fly them back to Britain.

Here, the old General, who had been de Gaulle’s senior officer during the fall of France, met his erstwhile junior commander and accepted from him the post of head of the Secret Army in France under de Gaulle’s leadership. His task was to fuse together all troops and paramilitary organizations, set up a General Staff and create six autonomous regional military organizations, each of which should, over time, be able ‘to play a role in the [eventual] liberation of the territory of France’. Delestraint’s first act was to write a letter under his new alias, ‘Vidal’, to ‘The officers and men of all Resistance paramilitary units’:

By order of General de Gaulle, I have taken command of the Underground Army from 11 November 1942.

To all I send greetings. In present circumstances, with the enemy entrenched everywhere in France, it is imperative to join up our military formations now in order to form the nucleus of the Underground Army, of which I hold the command. The moment is drawing near when we will be able to strike. The time is past for hesitation. I ask all to observe strict discipline in true military fashion. We shall fight together against the invader, under General de Gaulle and by the side of our Allies, until complete victory.