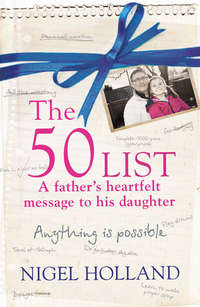

The 50 List – A Father’s Heartfelt Message to his Daughter: Anything Is Possible

For my darling wife, Lisa, and my wonderful children, Mattie, Amy and Ellie: with you beside me, I know anything is possible

Thanks also to my brothers, Mark and Gary, and my sister, Nicola: your love and support means everything to me

Finally, dear Mum and Dad: thanks for everything

‘All men dream, but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds, wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act on their dreams with open eyes, to make them possible.’

T. E. LAWRENCE

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

SEPTEMBER

NOVEMBER

DECEMBER

FEBRUARY

MARCH

APRIL

MAY

JUNE

JULY

AUGUST

SEPTEMBER

OCTOBER

NOVEMBER

DECEMBER

Epilogue

The 50 List

My Comedy Sketch

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Just like any parent, I want the best for my children. I want them to feel safe, to be confident and to grow up with the understanding that life is to be challenged: to be explored and enjoyed, no matter what obstacles you might have to face. My wife and I have three great children and I am very proud of them. The two eldest, Matthew (15) and Amy (13), have grown up with responsibilities that most of their peers have never experienced. I am in a wheelchair, and being a wheelchair-using dad limits me from doing some of the things that other dads do, like football and cycling – activities that other parents take for granted. But their understanding of the issues I face makes the relationship I have with my children what it is: close, loving and, most of all, fun. They are growing up to be caring and thoughtful individuals with an empathy that belies their ages.

Ten years ago my wife, Lisa, gave birth to our youngest daughter, Eleanor. She has been diagnosed with the same condition that I have: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) or peroneal muscular atrophy, also known as hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy. What this means in practical terms is that there is wastage of the muscles in the lower part of the limbs. I can no longer walk and my hand strength is very weak, limiting my dexterity. Ellie is walking still but her gait – the way she walks – is affected. In 2010 she had to undergo surgery on her legs to try to straighten her ankles, as her tendons were pulling her feet inwards. The disability can affect people in many different ways.

Both my wife and I want to see Ellie enjoy life just as much as her older siblings and we are aware that she will face problems as she grows up, but what we want her to understand is that those problems can be overcome. In my life I have done many crazy and wonderful things that many people thought were beyond my capabilities: water-skiing, off-road 4x4, go-karting, gliding, diving – the list goes on. I even played drums in a band in the 1980s, reaching the dizzy heights of playing the Hippodrome at Leicester Square. Up until 2010 I was competing in the National Drag Racing Championships in a powerful Ford Mustang race car. I’ve never let anything stop me from realizing my dreams, so I want Ellie to know that her capabilities are to be explored. And it’s not just that there’s nothing wrong with ‘having a go’, either. It’s that you’ll never know what you can do till you try.

Then, one day, not so long ago, something else struck me: that there’s a saying – or, more correctly, an idiom – that we all know, which goes ‘actions speak louder than words’. And as soon as it occurred to me, that was it; I was away. I wouldn’t just tell her. I would show her.

Nigel Holland, December 2012

SEPTEMBER

‘Dad,’ Ellie says to me, ‘you’re mad.’

‘Well, you knew that already,’ I say, grinning at the look of incomprehension on her face as she works her way down the piece of paper in her hand. It is a list. A list of all the crazy things I plan to do over the coming months. I can tell they’re crazy just by looking at the expression on her face.

‘Yeah, I know, Dad,’ she says, ‘but this is a big list. How are you going to do everything on it in one year?’

‘I’m going to be doing even more than that,’ I correct her. ‘Because it’s not finished yet. I was hoping you could suggest some things to put on it too.’

She looks again, her slender index finger tracing a line down the page. It’s actually two lists, one marked ‘extreme’ and one marked ‘other’. Ellie points to an item marked ‘extreme’.

‘What’s this?’ she asks.

‘Zorbing?’ I say, reading it. ‘Oh, it’s great fun. It’s rolling down a hill inside a very large bouncy ball.’

She takes this in, and her look of incomprehension doesn’t change. Though I’ve tried to explain to Ellie the main reason why I’m doing this – to inspire her – Ellie has a learning difficulty, which means she doesn’t always get the bigger picture. But perhaps she doesn’t need to. Not now, at least. All I really want is that she gets caught up in the excitement and thinks ‘can’ rather than ‘can’t’. That’ll be good enough for me. Though, hmm, ‘zorbing’ – she’s probably right: I am mad.

It’s late in the afternoon, the watery late-September sun is almost gone now, and we’re contemplating what seemed like a brilliant idea when I first thought of it, but which now seems to mark me out as bonkers: a list of 50 challenges, of all kinds, to be completed within the year, to prove that a) you really can do almost anything that you put your mind to and b) turning 50 doesn’t spell the end of any sort of life other than the pipe-and-slippers kind.

Because that’s what had struck me a couple of weeks earlier when a work colleague had mentioned my upcoming 50th birthday, saying that 50 – the big 50 – was a particularly depressing milestone. One that marked the end of youth and the beginning of ‘being old’, which was something I was not prepared to be. ‘And your point?’ I’d retorted, rising swiftly to the bait. ‘I don’t mind getting old, but I refuse to grow up.’ It was a thought – and a mindset – that had stayed with me all day.

And here we were, the idea having not only taken root but also sprouted. And what had started as a whimsical, unfocused kind of wish list had somehow become a full-blown plan. A plan to prove something to both myself and my children – particularly my youngest, ‘disabled’ daughter.

‘OK,’ I say to Ellie. ‘You think of some challenges.’

She considers it for a few seconds, chewing thoughtfully on her lower lip. ‘Erm, maybe jump over a tall building?’ she offers finally. And I’m pretty sure she’s only half joking.

Which is nice – it’s always good to be your children’s superhero – but her idea is not do-able. Even for me. I say so.

‘What about flying, then?’ she says.

‘What, you mean as in a plane?’

‘No,’ she retorts, in all seriousness. ‘Like Superman!’

Silly me. I should have known. Of course she means like Superman. I am her hero, just the same way my dad was my hero. It’s almost 30 years now since I lost him – over half a lifetime. And I still can’t believe he’s never coming back.

‘Ah,’ I tell Ellie, ‘there’s a problem with that one. I don’t have any red underpants that will fit over my trousers.’

She knows she’s being teased and pulls her ‘Dad, I’m being teased’ face. ‘Well,’ I say, ‘you started it. What do you expect? But I can sort of fly,’ I say, pointing to another item I’ve already added. ‘Indoor skydiving. That’s pretty much like flying.’

‘What, you can fly?’ She looks impressed now. ‘What, with no strings or anything?’

‘With no strings or anything. The air holds you up.’ I try to explain how it works, but I’m not sure she quite gets it. ‘Come on,’ I say. ‘What else? Think – what would you like to do, if you could do a challenge yourself?’

‘Fly a kite,’ she says, decisively. ‘I’d like to fly a kite – a big pink one. Hey, but Dad?’

‘What?’

‘I’ve got a brilliant one for you. Dye your hair pink!’

She is bright eyed with excitement at this unexpected brainwave. Perhaps a little too bright eyed for my liking.

‘Okaaayyy,’ I say slowly. ‘That can go under “maybe”.’

Ellie shakes her head. ‘You can’t do maybes. You have to definitely promise.’

I try to regroup. How on earth am I going to get out of this one? The plan is to do all this stuff to inspire others, her included; not to look like a complete idiot, for a bet.

‘I can’t promise definitely,’ I say. ‘I might not have time to fit them all in, might I?’

‘But if you do …’

‘Then how about I put it on my “reserve list”?’ I suggest. I have my clients to think about, after all. I write ‘reserve list’ on the bottom, followed by ‘Dye hair pink’. Which her expression seems to suggest might have mollified her. ‘Anything else?’ I ask, trying to redirect her thoughts a bit. Which is probably tempting fate, but never mind.

‘What about a puzzle?’ she suggests.

‘A jigsaw puzzle?’

‘Yes. A jigsaw puzzle.’

‘You know what, Ellie?’ I say, already picking up my pencil. ‘That is an excellent idea. Assuming you’ll help me, of course.’ I wiggle my fingers, which are probably cursing me already for the torture I am about to inflict on them.

‘Course I’ll help you,’ she says. ‘I’m brilliant at puzzles.’

‘OK,’ I say, adding it. ‘How many pieces should we go for?’

‘Five thousand,’ she says, without a flicker of hesitation. ‘That won’t be too hard for your fingers, will it, Dad?’

‘Piece of cake,’ I tell my daughter. And at that point I believe it.

Mad. Just as Ellie has already said.

NOVEMBER

11 November 2011

Number of challenges still to be completed: 50.

Number of times I have wondered what I’ve let myself in for: Already too numerous to count.

Now I’m up and running with this thing, there’s no backing out. No, I know I’m not exactly running yet – my plan is so far little more than a sketched-out idea – but having come up with it, I realize that committing to all these challenges is beginning to feel more and more like a challenge in itself. It’s one thing telling yourself you’re going to be able to achieve all of them, but quite another when you tell everyone else you are as well. Another still when the person you most want to do it for is one of the people dearest to you in the world.

As it turns out, I have been somewhat beaten off the blocks anyway, in terms of challenges, because only two weeks after formulating the plan, and my subsequent optimistic conversation with Ellie, I had another one lobbed into my lap. And it was a big one. A particularly big one for a man of my age. After 13 happy years working as a web developer, I was made redundant from my job.

Sitting in the room that was once my study but has now been re-christened my ‘office’, in recognition of this new and exciting life stage, I think of Tommy Cooper and I smile. ‘Just like that’ – wasn’t that his tag line? I was made redundant, just like that. At least that’s the way it feels to me, though perhaps I should have seen it coming. Yet at the same time, I can’t stop thinking about the timing of everything. Perhaps fate’s played a part in all this happening when it has, because now nothing stands in the way of my doing what I’ve set out to do. I am all out of excuses. I have time on my hands. I also have a new item to add to my list of challenges: ‘Make my business work.’ Which is handy, because the zero gravity flight that it has now taken the place of was way too expensive to even begin to contemplate, and even more so for a guy with a family and a mortgage, but – crucially, and suddenly – without a job.

But it was definitely a job I’m going to miss. Though in recent years, after my firm was taken over by an American company, morale was low, stress was high and business was a bit shaky, the timing of the redundancy, in one sense, couldn’t have been worse. During the last few months I was working for a really great manager, and though mostly from home – which was isolating, as I felt cut off from the office gossip – I felt energized about work in a way I hadn’t in a long time, and I’m sad that it’s all come to an end.

There was also the big question to face: how on earth would I pay the mortgage? But, though the simple option would be to take my skills and go and find another job with them, I had, and still have, a nagging sense that I should be taking the plunge and going it alone. Now or never. And I’m definitely less keen on never.

Which leaves me with now – do or die. Which is exciting yet scary.

So sending off my entry form for the Silverstone half marathon seems a little less daunting as a consequence. Though on the one hand it feels like one of the most difficult of all the challenges – 13 miles, and in a wheelchair: I am going to need to train and then some – when I compare it to the career cliff face I’ve just been forced to jump from (hoping to fly, obviously, rather than fall flat on my face) it feels suddenly more in the realms of the ‘actually achievable’: a solid thing, something I have control over.

As I sit at my desk filling in the online application form, I get a picture in my head of my beloved parents. Sadly, I don’t have many pictures of them together. I have old, individual ones, taken with primitive cameras, black, white and sepia, and fluffy-edged with age. But nothing recent. Not many that show how much they loved one another. If I could change one thing in my life it would be that they could be here to see me do this. You never lose that feeling, I think, whatever your age.

* * *

According to family folklore, which is generally the most dubious kind, I always liked making an entrance. There must be some truth in it, though, because the story goes that when I first looked like arriving, on 8 December 1962, my mother was busy serving dinner to no fewer than 12 guests.

I was the third of three boys (which perhaps explains my mother’s cool head in the face of a dozen hungry dinner guests), my brothers Mark and Gary then being six and four respectively. But I didn’t keep my privileged position for very long. No sooner had I turned two than my world was disrupted – by the arrival of my baby sister, Nicola.

Nikki’s arrival caused disruption in other ways as well. Unplanned, she came under the banner of ‘unexpected gifts from heaven’, but for me and my brothers she was anything but. We had wanted a dog. We had been promised a dog. Well, if not exactly promised, certainly given to believe that having a dog was not entirely out of the question. So for the duration of the pregnancy, we were miffed (though in my case, possibly still hopeful she might turn out to be a dog) and according to my mother, we spent the first six months of her life demanding that she be called Rover.

‘Just as well you were a girl,’ I recall my mother telling her later, ‘or that might actually have turned out to be your name.’

The house the family lived in when I was born was in Britannia Square in Worcester. I have only a few memories of my time there. The house stood very tall, with three storeys, and was painted bright white. In my mind’s eye, it was very grand looking, our family residence, though as a small child I naturally had a small child’s perspective, so perhaps it wasn’t quite as grand as it seemed.

Either way, it was home, and it was a happy home as well. Though my memories of it are no more than snapshots, I recall a wind-up mouse, which I wound and launched accidentally into my potty – the potty into which I’d just peed. I also have a clear early memory of my dad stepping out onto the roof of the house to sort out some tiling that had come loose. He was a jack of all trades, Dad – a builder, decorator and, at that time, a bus driver, and I can still recall how incredible it felt to look up and see him, high above my head, fixing the roof.

We didn’t stay in Worcester for long. According to another piece of family folklore, my dad could drive anything – cars and buses, coaches and trucks, huge articulated lorries. If it had wheels and an engine, he was fine with it. As a result, within a couple of years of my sister’s birth, Dad had found a new job. A better-paid one – which was key, given that he had a young and growing family – as a driver for BEA at Heathrow Airport.

* * *

Having sent in the entry form for the Silverstone half marathon, there is no turning back, and even if there were, I decide to seal the deal by announcing that I am taking part in it on Facebook, for good measure. As with telling all your mates you plan to give up smoking, putting it out there means there is NO WAY I can back out of it now.

For all my efficiency in telling the world what I’m up to, though, it’s still going to be quite a leap of imagination to actually see myself completing a half marathon. And if my plan is to have any sort of credibility – not least with me – it’s a leap I’d better start getting fit for.

Which means training. And training means several things must happen: hours of training itself, yes, but I must also cultivate a mindset of self-discipline and a big stock of dedication. Though in reality, I don’t have a clue what I need to do to prepare. Note to self: so hurry up and find out!

DECEMBER

6 December 2011

Number of shopping days till Christmas: 19.

Number of days till my 49th birthday: 3.

Ergo, number of days till my 50th birthday: 368.

Number of challenges that need to be completed per day, therefore, on average: 0.137741.

Number of challenges that have actually been completed per day, on average: 0.000000.

Well, I’ve been busy training, haven’t I? I have just, in fact, returned from a 5-mile training lap around the town. And I have decided upon a new motivational slogan: if I can make it around Wellingborough, I can make it anywhere. (Which will obviously, of necessity, include Silverstone.) No, it doesn’t have quite the same ring as the lyric from ‘New York, New York’, but it is what I believe to be true.

It’s all about motivation, obviously. The way the weather is looking right now, I might not get another chance to get out and train till after Christmas, so it feels good to have got the laps I have done in the bag. Admittedly, a half marathon is 13 miles, not 5, but in terms of conditions there’s no contest. What with the state of the roads and pavements, pot holes, broken kerbs – not to mention countless badly parked cars – just negotiating the route of my training lap is a major challenge. It’s also pretty hilly, which, in a wheelchair, is hard on the arms, so all things considered (and wheeling round, I’ve had plenty of time to consider) 13 miles on a perfectly smooth, level racetrack doesn’t daunt me quite so much now.

I Skype my brother Gary, who lives just outside Frankfurt in Germany. He studied performance sports at school and still plays squash at a high level, so is the ideal person to give me training tips and encouragement. He tells me to eat carbs, drink plenty of water, practise having a positive mental attitude and generally live a life of such wholesome sobriety till March that as soon as we’re done I feel a compulsion to crack open a large beer.

10 December 2011

Number of years on the planet now: 49. And I don’t feel a day older than 77 (post-training complications – i.e. I hurt).

Number of challenges completed: Erm … still have not quite done any yet.

However, bottles of good Merlot consumed: 1.

I was 49 yesterday, and the thing that most sticks in my mind is that I now have just 364 days to complete all 50 challenges, or else I am going to look something of an idiot. It was a nice birthday – though we dubbed it something different. As Lisa and I dined from the Christmas lunchtime menu at the Beckworth Garden Emporium (and why not? They have a cracking restaurant) we decided we’d call it the Mantisweb staff Christmas party, Mantisweb being the name I’ve given my new business. Which of course gave us licence to misbehave generally, though neither of us actually photocopied our bottoms.

My birthday over – Christmas isn’t allowed to begin until it is – the festivities are coming around super-fast now, and Lisa and I still don’t know what to get the kids. With all my redundancy pay already allocated to pay the mortgage, money’s tight, so it’s not going to be an extravagant affair this year. I find I don’t see that as a bad thing, particularly. Perhaps it’s good to keep things a little simpler – more like the Christmases of my own youth, when there were only three TV channels, there was no 24/7 scheduling, and a snowball wasn’t just something you lobbed at your mates but some foul, yellow, frothy thing your mum drank. Well, my mum did, anyway, and whichever way you look at it, I can’t help but look back at Christmases past and wish Christmases present were just a little more like them.