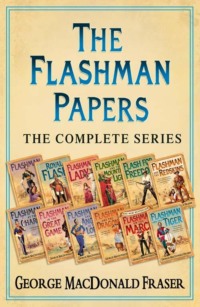

The Flashman Papers: The Complete 12-Book Collection

“Well, I’m damned!” he said, when I had finished, and poured himself another glass. He wasn’t grinning, but his brow had cleared. “You young dog! A pretty state of things, indeed. Expelled in disgrace, by gad! Did he flog you? No? I’d have had the hide off your back – perhaps I will, damme!” But he was smiling now, a bit sour, though. “What d’you make of this, Judy?” he said to the woman.

“I take it this is a relative?” she says, letting her fan droop towards me. She had a deep husky voice, and I shivered again.

“Relative? Eh? Oh, dammit, it’s my son Harry, girl! Harry, this is Judy … er, Miss Parsons.”

She smiled at me now, still with that half-amused look, and I preened myself – I was seventeen, remember – and sized up her points while the father got himself another glass and damned Arnold for a puritan hedge-priest. She was what is called junoesque, broad-shouldered and full-breasted, which was less common then than it is now, and it seemed to me she liked the look of Harry Flashman.

“Well,” said my father at last, when he had finished fulminating against the folly of putting prigs and scholars in charge of public schools. “Well, what’s to be done with you, eh? What’ll you do, sir? Now that you’ve disgraced the home with your beastliness, eh?”

I had been thinking this over on my way home, and said straight out that I fancied the army.

“The army?” he growled. “You mean I’m to buy you colours so that you can live like a king and ruin me with bills at the Guards’ Club, I suppose?”

“Not the Guards,” I said. “I’ve a notion for the 11th Light Dragoons.”

He stared at this. “You’ve chosen a regiment already? By gad, here’s a cool hand!”

I knew the 11th were at Canterbury, after long service in India, and unlikely for that reason to be posted abroad. I had my own notions of soldiering. But this was too fast for the guv’nor; he went on about the expense of buying in, and the cost of army life, and worked back to my expulsion and my character generally, and so back to the army again. The port was making him quarrelsome, I could see, so I judged it best not to press him. He growled on:

“Dragoons, damme! D’ye know what a cornet’s commission costs? Damned nonsense. Never heard the like. Impudence, eh, Judy?”

Miss Judy observed that I might look very well as a dashing dragoon.

“Eh?” said my father, and gave her a queer look. “Aye, like enough he would. We’ll see.” He looked moodily at me. “In the meantime, you can get to your bed,” he said. “We’ll talk of this tomorrow. For the moment you’re still in disgrace.” But as I left them I could hear him blackguarding Arnold again, so I went to bed well pleased, and relieved into the bargain. He was odd fish, all right; you could never tell how he would take anything.

In the morning, though, when I met my father at breakfast, there was no talk of the army. He was too busy damning Brougham – who had, I gathered, made a violent attack on the Queen in the House1 – and goggling over some scandal about Lady Flora Hastings2 in the Post, to give me much attention, and left presently for his club. Anyway, I was content to let the matter rest just now; I have always believed in one thing at a time, and the thing that was occupying my mind was Miss Judy Parsons.

Let me say that while there have been hundreds of women in my life, I have never been one of those who are forever boasting about their conquests. I’ve raked and ridden harder than most, no doubt, and there are probably a number of middle-aged men and women who could answer to the name of Flashman if only they knew it. That’s by the way; unless you are the kind who falls in love – which I’ve never been – you take your tumbles when you’ve the chance, and the more the better. But Judy has a close bearing on my story.

I was not inexperienced with women; there had been maids at home and a country girl or two, but Judy was a woman of the world, and that I hadn’t attempted. Not that I was concerned on that account, for I fancied myself (and rightly) pretty well. I was big and handsome enough for any of them, but being my father’s mistress she might think it too risky to frolic with the son. As it turned out, she wasn’t frightened of the guv’nor or anyone else.

She lived in the house – the young Queen was newly on the throne then, and people still behaved as they had under the Prince Regent and King Billy; not like later on, when mistresses had to stay out of sight. I went up to her room before noon to spy out the land, and found her still in bed, reading the papers. She was glad to see me, and we talked, and from the way she looked and laughed and let me toy with her hand I knew it was only a question of finding the time. There was an abigail fussing about the room, or I’d have gone for her then and there.

However, it seemed my father would be at the club that night, and playing late, as he often did, so I agreed to come back and play écarte with her in the evening. Both of us knew it wouldn’t be cards we would be playing. Sure enough, when I did come back, she was sitting prettying herself before her glass, wearing a bed-gown that would have made me a small handkerchief. I came straight up behind her, took her big breasts out in either hand, stopped her gasp with my mouth, and pushed her on to the bed. She was as eager as I was, and we bounced about in rare style, first one on top and then the other. Which reminds me of something which has stayed in my head, as these things will: when it was over, she was sitting astride me, naked and splendid, tossing the hair out of her eyes – suddenly she laughed, loud and clearly, the way one does at a good joke. I believed then she was laughing with pleasure, and thought myself a hell of a fellow, but I feel sure now she was laughing at me. I was seventeen, you remember, and doubtless she found it amusing to know how pleased with myself I was.

Later we played cards, for form’s sake, and she won, and then I had to sneak off because my father came home early. Next day I tried her again, but this time, to my surprise, she slapped my hands and said: “No, no, my boy; once for fun, but not twice. I’ve a position to keep up here.” Meaning my father, and the chance of servants gossiping, I supposed.

I was annoyed at this, and got ugly, but she laughed at me again. I lost my temper, and tried to blackmail her by threatening to let my father find out about the night before, but she just curled her lip.

“You wouldn’t dare,” she said. “And if you did, I wouldn’t care.”

“Wouldn’t you?” I said. “If he threw you out, you slut?”

“My, the brave little man,” she mocked me. “I misjudged you. At first sight I thought you were just another noisy brute like your father, but I see you’ve a strong streak of the cur in you as well. Let me tell you, he’s twice the man you are – in bed or out of it.”

“I was good enough for you, you bitch,” I said.

“Once,” she said, and dropped me a mock curtsey. “That was enough. Now get out, and stick to servant girls after this.”

I went in a black rage, slamming the door, and spent the next hour striding about the Park, planning what I would do to her if I ever had the chance. After a while my anger passed, and I just put Miss Judy away in a corner of my mind, as one to be paid off when the chance came.

Oddly enough, the affair worked to my advantage. Whether some wind of what had happened on the first night got to my father’s ears, or whether he just caught something in the air, I don’t know, but I suspect it was the second; he was shrewd, and had my own gift of sniffing the wind. Whatever it was, his manner towards me changed abruptly; from harking back to my expulsion and treating me fairly offhand, he suddenly seemed sulky at me, and I caught him giving me odd looks, which he would hurriedly shift away, as though he were embarrassed.

Anyway, within four days of my coming home, he suddenly announced that he had been thinking about my notion of the army, and had decided to buy me a pair of colours. I was to go over to the Horse Guards to see my Uncle Bindley, my mother’s brother, who would arrange matters. Obviously, my father wanted me out of the house, and quickly, so I pinned him then and there, while the iron was hot, on the matter of an allowance. I asked for £500 a year to add to my pay, and to my astonishment he agreed without discussion. I cursed myself for not asking £750 but £500 was twice what I’d expected, and far more than enough, so I was pretty pleased, and set off for Horse Guards in a good humour.

A lot has been said about the purchase of commissions – how the rich and incompetent can buy ahead of better men, how the poor and efficient are passed over – and most of it, in my experience, is rubbish. Even with purchase abolished, the rich rise faster in the Service than the poor, and they’re both inefficient anyway, as a rule. I’ve seen ten men’s share of service, through no fault of my own, and can say that most officers are bad, and the higher you go, the worse they get, myself included. We were supposed to be rotten with incompetence in the Crimea, for example, when purchase was at its height, but the bloody mess they made in South Africa recently seems to have been just as bad – and they didn’t buy their commissions.

However, at this time I’d no thought beyond being a humble cornet, and living high in a crack regiment, which was one of the reasons I had fixed on the 11th Dragoons. Also, that they were close to town.

I said nothing of this to Uncle Bindley, but acted very keen, as though I was on fire to win my spurs against the Mahrattas or the Sikhs. He sniffed, and looked down his nose, which was very high and thin, and said he had never suspected martial ardour in me.

“However, a fine leg in pantaloons and a penchant for folly seem to be all that is required today,” he went on. “And you can ride, as I collect?”

“Anything on legs, uncle,” says I.

“That is of little consequence, anyway. What concerns me is that you cannot, by report, hold your liquor. You’ll agree that being dragged from a Rugby pothouse, reeling, I believe, is no recommendation to an officers’ mess?”

I hastened to tell him that the report was exaggerated.

“I doubt it,” he said. “The point is, were you silent in your drunken state, or did you rave? A noisy drunkard is intolerable; a passive one may do at a pinch. At least, if he has money; money will excuse virtually any conduct in the army nowadays, it seems.”

This was a favourite sneer of his; I may say that my mother’s family, while quality, were not over-rich. However, I took it all meekly.

“Yes,” he went on, “I’ve no doubt that with your allowance you will be able either to kill or ruin yourself in a short space of time. At that, you will be no worse than half the subalterns in the service, if no better. Ah, but wait. It was the 11th Light Dragoons, wasn’t it?”

“Oh, yes, uncle.”

“And you are determined on that regiment?”

“Why, yes,” I said, wondering a little.

“Then you may have a little diversion before you go the way of all flesh,” said he, with a knowing smile. “Have you, by any chance, heard of the Earl of Cardigan?”

I said I had not, which shows how little I had taken notice of military affairs.

“Extraordinary. He commands the 11th, you know. He succeeded to the title only a year or so ago, while he was in India with the regiment. A remarkable man. I understand he makes no secret of his intention to turn the 11th into the finest cavalry regiment in the army.”

“He sounds like the very man for me,” I said, all eagerness.

“Indeed, indeed. Well, we mustn’t deny him the service of so ardent a subaltern, must we? Certainly the matter of your colours must be pushed through without delay. I commend your choice, my boy. I’m sure you will find service under Lord Cardigan – ah – both stimulating and interesting. Yes, as I think of it, the combination of his lordship and yourself will be rewarding for you both.”

I was too busy fawning on the old fool to pay much heed to what he was saying, otherwise I should have realised that anything that pleased him would probably be bad for me. He prided himself on being above my family, whom he considered boors, with some reason, and had never shown much but distaste for me personally. Helping me to my colours was different, of course; he owed that as a duty to a blood relation, but he paid it without enthusiasm. Still, I had to be civil as butter to him, and pretend respect.

It paid me, for I got my colours in the 11th with surprising speed. I put it down entirely to influence, for I was not to know then that over the past few months there had been a steady departure of officers from the regiment, sold out, transferred, and posted – and all because of Lord Cardigan, whom my uncle had spoken of. If I had been a little older, and moved in the right circles, I should have heard all about him, but in the few weeks of waiting for my commission my father sent me up to Leicestershire, and the little time I had in town I spent either by myself or in the company of such of my relatives as could catch me. My mother had had sisters, and although they disliked me heartily they felt it was their duty to look after the poor motherless boy. So they said; in fact they suspected that if I were left to myself I would take to low company, and they were right.

However, I was to find out about Lord Cardigan soon enough.

In the last few days of buying my uniforms, assembling the huge paraphernalia that an officer needed in those days – far more than now – choosing a couple of horses, and arranging for my allowance, I still found time on my hands, and Mistress Judy in my thoughts. My tumble with her had only whetted my appetite for more of her, I discovered; I tried to get rid of it with a farm girl in Leicestershire and a young whore in Covent Garden, but the one stank and the other picked my pocket afterwards, and neither was any substitute anyway. I wanted Judy, at the same time as I felt spite for her, but she had avoided me since our quarrel and if we met in the house she simply ignored me.

In the end it got too much, and the night before I left I went to her room again, having made sure the guv’nor was out. She was reading, and looking damned desirable in a pale green negligée; I was a little drunk, and the sight of her white shoulders and red mouth sent the old tingle down my spine again.

“What do you want?” she said, very icy, but I was expecting that, and had my speech ready.

“I’ve come to beg pardon,” I said, looking a bit hangdog. “Tomorrow I go away, and before I went I had to apologise for the way I spoke to you. I’m sorry, Judy; I truly am; I acted like a cad … and a ruffian, and, well … I want to make what amends I can. That’s all.”

She put down her book and turned on her stool to face me, still looking mighty cold, but saying nothing. I shuffled like a sheepish schoolboy – I could see my reflection in the mirror behind her, and judge how the performance was going – and said again that I was sorry.

“Very well, then,” she said at last. “You’re sorry. You have cause to be.”

I kept quiet, not looking at her.

“Well, then,” she said, after a pause. “Good night.”

“Please, Judy,” I said, looking distraught. “You make it very hard. If I behaved like a boor –”

“You did.”

“– it was because I was angry and hurt and didn’t understand why … why you wouldn’t let me …” I let it trail off and then burst out that I had never known a woman like her before, and that I had fallen in love with her, and only came to ask her pardon because I couldn’t bear the thought of her detesting me, and a good deal more in the same strain – simple enough rubbish, you may think, but I was still learning. At that, the mirror told me I was doing well. I finished by drawing myself up straight, and looking solemn, and saying:

“And that is why I had to see you again … to tell you. And to ask your pardon.”

I gave her a little bow, and turned to the door, rehearsing how I would stop and look back if she didn’t stop me. But she took me at face value, for as I put my hand to the latch she said:

“Harry.” I turned round, and she was smiling a little, and looking sad. Then she smiled properly, and shook her head and said:

“Very well, Harry, if you want my pardon, for what it’s worth you have it. We’ll say no …”

“Judy!” I came striding back, smiling like soul’s awakening. “Oh, Judy, thank you!” And I held out my hand, frank and manly.

She got up and took it, smiling still, but there was none of the old wanton glint about her eye. She was being stately and forgiving, like an aunt to a naughty nephew. The nephew, had she known it, was intent on incest.

“Judy,” I said, still holding her hand, “we’re parting friends?”

“If you like,” she said, trying to take it away. “Goodbye, Harry, and good luck.”

I stepped closer and kissed her hand, and she didn’t seem to mind. I decided, like the fool I was, that the game was won.

“Judy,” I said again, “you’re adorable. I love you, Judy. If only you knew, you’re all I want in a woman. Oh, Judy, you’re the most beautiful thing, all bum, belly and bust, I love you.”

And I grabbed her to me, and she pulled free and got away from me.

“No!” she said, in a voice like steel.

“Why the hell not?” I shouted.

“Go away!” she said, pale and with eyes like daggers. “Goodnight!”

“Goodnight be damned,” says I. “I thought you said we were parting friends? This ain’t very friendly, is it?”

She stood glaring at me. Her bosom was what the lady novelists call agitated, but if they had seen Judy agitated in a negligée they would think of some other way of describing feminine distress.

“I was a fool to listen to you for a moment,” she says. “Leave this room at once!”

“All in good time,” says I, and with a quick dart I caught her round the waist. She struck at me, but I ducked it, and we fell on the bed together. I had hold of the softness of her, and it maddened me. I caught her wrist as she struck at me again, like a tigress, and got my mouth on hers, and she bit me on the lip for all she was worth.

I yelped and broke away, holding my mouth, and she, raging and panting, grabbed up some china dish and let fly at me. It missed by a long chalk, but it helped my temper over the edge completely. I lost control of myself altogether.

“You bitch!” I shouted, and hit her across the face as hard as I could. She staggered, and I hit her again, and she went clean over the bed and on to the floor on the other side. I looked round for something to go after her with, a cane or a whip, for I was in a frenzy and would have cut her to bits if I could. But there wasn’t one handy, and by the time I had got round the bed to her it had flashed across my mind that the house was full of servants and my full reckoning with Miss Judy had better be postponed to another time.

I stood over her, glaring and swearing, and she pulled herself up by a chair, holding her face. But she was game enough.

“You coward!” was all she would say. “You coward!”

“It’s not cowardly to punish an insolent whore!” says I. “D’you want some more?”

She was crying – not sobbing, but with tears on her cheeks. She went over to her chair by the mirror, pretty unsteady, and sat down and looked at herself. I cursed her again, calling her the choicest names I could think of, but she worked at her cheek, which was red and bruised, with a hare’s foot, and paid no heed. She did not speak at all.

“Well, be damned to you!” says I, at length, and with that I slammed out of the room. I was shaking with rage, and the pain in my lip, which was bleeding badly, reminded me that she had paid for my blows in advance. But she had got something in return, at all events; she would not forget Harry Flashman in a hurry.

Chapter 3

The 11th Light Dragoons at this time were newly back from India, where they had been serving since before I was born. They were a fighting regiment, and – I say it without regimental pride, for I never had any, but as a plain matter of fact – probably the finest mounted troops in England, if not in the world. Yet they had been losing officers, since coming home, hand over fist. The reason was James Brudenell, Earl of Cardigan.

You have heard all about him, no doubt. The regimental scandals, the Charge of the Light Brigade, the vanity, stupidity, and extravagance of the man – these things are history. Like most history they have a fair basis of fact. But I knew him, probably as few other officers knew him, and in turn I found him amusing, frightening, vindictive, charming, and downright dangerous. He was God’s own original fool, there’s no doubt of that – although he was not to blame for the fiasco at Balaclava; that was Raglan and Airey between them. And he was arrogant as no other man I’ve ever met, and as sure of his own unshakeable rightness as any man could be – even when his wrong-headedness was there for all to see. That was his great point, the key to his character: he could never be wrong.

They say that at least he was brave. He was not. He was just stupid, too stupid ever to be afraid. Fear is an emotion, and his emotions were all between his knees and his breastbone; they never touched his reason, and he had little enough of that.

For all that, he could never be called a bad soldier. Some human faults are military virtues, like stupidity, and arrogance, and narrow-mindedness. Cardigan blended all three with a passion for detail and accuracy; he was a perfectionist, and the manual of cavalry drill was his Bible. Whatever rested between the covers of that book he could perform, or cause to be performed, with marvellous efficiency, and God help anyone who marred that performance. He would have made a first-class drill sergeant – only a man with a mind capable of such depths of folly could have led six regiments into the Valley at Balaclava.

However, I devote some space to him because he played a not unimportant part in the career of Harry Flashman, and since it is my purpose to show how the Flashman of Tom Brown became the glorious Flashman with four inches in Who’s Who and grew markedly worse in the process, I must say that he was a good friend to me. He never understood me, of course, which is not surprising. I took good care not to let him.

When I met him in Canterbury I had already given a good deal of thought to how I should conduct myself in the army. I was bent on as much fun and vicious amusement as I could get – my contemporaries, who praise God on Sundays and sneak off to child-brothels during the week, would denounce it piously as vicious, anyway – but I have always known how to behave to my superiors and shine in their eyes, a trait of mine which Hughes pointed out, bless him. This I had determined on, and since the little I knew of Cardigan told me that he prized smartness and show above all things, I took some pains over my arrival in Canterbury.

I rolled up to regimental headquarters in a coach, resplendent in my new uniform, and with my horses led behind and a wagonload of gear. Cardigan didn’t see me arrive, unfortunately, but word must have been carried to him, for when I was introduced to him in his orderly room he was in good humour.

“Haw-haw,” said he, as we shook hands. “It is Mr Fwashman. How-de-do, sir. Welcome to the wegiment. A good turn-out, Jones,” he went on to the officer at his elbow. “I delight to see a smart officer. Mr Fwashman, how tall are you?”

“Six feet, sir,” I said, which was near enough right.

“Haw-haw. And how heavy do you wide, sir?”

I didn’t know, but I guessed at twelve and a half stone.

“Heavy for a light dwagoon,” said he, shaking his head. “But there are compensations. You have a pwoper figure, Mr Fwashman, and bear yourself well. Be attentive to your duties and we shall deal very well together. Where have you hunted?”

“In Leicestershire, my lord,” I said.

“Couldn’t be better,” says he. “Eh, Jones? Very good, Mr Fwashman – hope to see more of you. Haw-haw.”

Now, no one in my life that I could remember had ever been so damned civil to me, except toad-eaters like Speedicut, who didn’t count. I found myself liking his lordship, and did not realise that I was seeing him at his best. In this mood, he was a charming man enough, and looked well. He was taller than I, straight as a lance, and very slender, even to his hands. Although he was barely forty, he was already bald, with a bush of hair above either ear and magnificent whiskers. His nose was beaky and his eyes blue and prominent and unwinking – they looked out on the world with that serenity which marks the nobleman whose uttermost ancestor was born a nobleman, too. It is the look that your parvenu would give half his fortune for, that unrufflable gaze of the spoiled child of fortune who knows with unshakeable certainty that he is right and that the world is exactly ordered for his satisfaction and pleasure. It is the look that makes underlings writhe and causes revolutions. I saw it then, and it remained changeless as long as I knew him, even through the roll-call beneath Causeway Heights when the grim silence as the names were shouted out testified to the loss of five hundred of his command. “It was no fault of mine,” he said then, and he didn’t just believe it; he knew it.