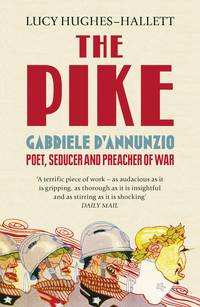

The Pike: Gabriele d’Annunzio, Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War

Rare and precious things, unfortunately, are expensive, and in the early 1880s, d’Annunzio, for all the volume of his work, was not earning nearly as much as he thought he needed. Meanwhile his responsibilities were growing. He and Maria passed the first fifteen months of their married life in Pescara, Francesco Paolo having allowed them the Villa Fuoco. There, in January 1884, their son Mario was born. D’Annunzio was not to prove a dependable father, but the birth moved him. ‘I went round and round the room like a beast in a cage … I could hear a feeble, sweet mewling … I don’t know how to tell you what I felt.’ He wrote dotingly about the little pink creature with blue eyes and a tiny, tiny mouth, and made plans for him. Mario would be a painter, or perhaps a scientist. His second novel, The Innocent, contains lovingly detailed descriptions of a baby’s tiny hands and wet gums, its wildly waving arms and unfocused eyes. The novel ends though, with the fictional father killing the infant, which is impeding its parents’ love life. Less than a month after Mario was born d’Annunzio reported that he had sent his baby to stay with its grandparents. ‘It yelled too much.’

In the Abruzzi he completed another collection of stories, heavily influenced by Flaubert, describing the sexual cravings of upper-class women. The volume was published that summer of 1884 by Sommaruga, with a jacket design featuring three nude women. D’Annunzio protested that the image was ‘indecent’. Author and publisher exchanged heated letters in the columns of the journals, but it has been plausibly suggested that this apparent falling out was contrived between them in order to publicise the book.

D’Annunzio was also sending articles back to the Roman journals, but he was running out of material. A piece on the brass bands which processed around Pescara on public holidays was a particularly desperate bit of barrel-scraping; privately d’Annunzio admitted to detesting the bands’ raucous music. He was missing his friends. ‘No one comes to see me,’ he wrote to Scarfoglio. He felt out of touch. He begged to be sent the latest journals. ‘Nothing reaches me here and I’m desperate.’ In November 1884, still only twenty-one years old, he returned to Rome, taking his wife and baby with him, to take up a job as an editor and regular contributor to La Tribuna.

Over the next four years, day after day, he was to write literally hundreds of pieces, vignettes of Roman social and cultural life. Sometimes he played the erudite critic: he reviewed books and exhibitions. In discussing Renan’s Life of Jesus he launched into a discursive piece on Homer’s Elysian fields. More often he was an observer of the frivolous ‘high life’. He wrote about funerals and race meetings, about concerts and parties. He gave a lasciviously detailed account of a meal eaten after a day’s hunting: hare with rosemary and thyme; goose-liver pâté with a glaze scented with truffles; champagne. He prescribed the most graceful way to take snuff. He laid down rules about what it was appropriate for a gentleman to wear to the opera.

He had a multiplicity of names. He wrote as Sir Charles Vere de Vere; as Lila Biscuit; as Happemouche; as Bull-Calf; as Puck or Bottom (in 1887 he announced that he was about to publish a translation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream – it never appeared); as Miching-Mallecho (another Shakespearean reference); as the Japanese Shiun Sui Katsu Kava and – most frequently – as Duke Minimo. These fake personae were not just names, but fully developed characters, each with their own servants, houses and social lives. He invented peccadilloes for them and spoke through their differentiated voices. Sir Charles Vere de Vere describes his friend Donna Claribel, and then quotes at length from the diary she keeps in a notebook bound with wild ass’s skin (d’Annunzio had discovered Balzac). Doubly distanced from its actual author, Donna Claribel’s account of a meet of the foxhounds is an airy piece of fiction, light and funny. D’Annunzio’s major works give no hint that he had any sense of humour whatsoever, but these early pieces are playful and droll. The hack-writer was not only observing settings and characters and situations which would be recreated by the novelist. He was also trying out fictional techniques.

His most-used pseudonym was a noble one, but there was a sad irony in the name Duke Minimo (least of the dukes). In one of the ‘Duke’s’ pieces he records how he and a group of friends have been refused access to a railway carriage. ‘We were repelled by main force, as though we were so many journalists.’ D’Annunzio was well aware how the person he actually was was viewed by the kind of person he aspired to be.

Andrea Sperelli, his fictional alter ego, lives in a huge, sumptuously decorated apartment in the Palazzo Zuccari, at the top of the Spanish Steps, around the corner from where d’Annunzio had rented one attic room next to a brothel. Elena Muti, d’Annunzio’s imaginary duchess, has an apartment in the Palazzo Barberini, where room after room is furnished with carved chests, classical busts, bronze platters and curtains embroidered with golden unicorns. D’Annunzio and his family lived in a cramped rented apartment in a narrow street nearby. In 1886 his second son, Gabriellino, was born. Veniero followed a year later. When Andrea Sperelli returns to his tapestry-hung rooms after a lunch party, he is at leisure to stretch languidly in front of his fire and muse on beauty and art until his manservant reminds him that it is time to dress for a dinner. His creator had deadlines to meet, bills to pay and, increasingly, creditors to placate. What he called the ‘miserable daily grind’ permitted him no respite.

Before going to a ball, Sperelli is invariably invited to dinner in one of Rome’s great palaces. D’Annunzio, by contrast, eating alone once in a beer shop, dozed off and dreamt of a ballroom all hung around with camellias and cradles. In each cradle there is a baby: each baby is crying loudly. The noise is excruciating. As the ballroom fills with couples, the gentlemen each take up several babies and attempt to dance while carrying them on their shoulders or under their armpits or beneath their waistcoats. The babies scream and wriggle, and poke their fingers into the dancer’s eyes, setting up such a hullabaloo that eventually the dreamer/writer awakes. It’s a dream that any exhausted new parent can identify with, that of a young father living in a small apartment with (at the time this piece was written) two children under the age of two and a half, striving to lead the exquisite life he so admired and coveted, but sleep-deprived and encumbered night and day by his offspring.

D’Annunzio’s need for money troubled him perhaps less than it ought to have done. Maria relates that, on receiving a fee desperately needed for the payment of household bills, he went ‘light and gay as a little bird’ to squander it all on a jade ornament. His compulsion to spend was at best reckless, at worst pathological.

He was not unmercenary. His correspondence demonstrates how much of his energy went into wheedling or browbeating his publishers into advancing him inordinately large sums against books as yet (and in some cases always to remain) unwritten. Once his novels were being published abroad, he studied exchange rates and timed his demands for the payments of his foreign royalties accordingly. When, in his famous middle age, he heard that a hotelier had, rather than banking his cheque, kept it for the sake of his autograph, he wondered if there was any way of persuading others to do likewise. But acquisitive as he was, he was also incorrigibly extravagant. While Maria, housekeeping for the first time in her hitherto privileged life, struggled to find cash for the butcher and baker, her husband allowed Sommaruga to pay him for his contributions to the Cronaca Bizantina with credit at the florist’s shop.

After two years at La Tribuna he wrote to the proprietor, Prince Maffeo Colonna di Sciarra, a letter which was in part a request for a pay rise, in part another literary self-portrait. ‘By temperament and by instinct I have a need for the superfluous.’ He must have beautiful things about him. ‘I could have lived very well in a modest house … taken tea in a threepenny cup, blown my nose on handkerchiefs at two lire the dozen … Instead, fatally, I have wanted Persian carpets, Japanese plates, bronzes, ivories, trinkets, all those useless, lovely things which I love with profound and ruinous passion.’ There is nothing apologetic about this self-description. An archangel cannot be expected to match his expenditure to the means available, after the manner of a penny-pinching tradesman. Nor can one of those superior beings whose role it is to ‘think and feel’. Prodigality is an aristocratic vice, a perverted form of largesse. Besides, d’Annunzio was not simply a self-indulgent squanderer (although he was that too). He was, in the most literal meaning of the word, an aesthete, one for whom the cult of beauty took the place of morality.

Writing art reviews and journalistic essays, d’Annunzio was pleased to be following the lead given by Baudelaire in the previous generation. The author of Les Fleurs du mal was also an influential art critic, and his essay on the ‘dandy’ defined a new kind of hero. ‘These beings have no other aim, but that of cultivating the idea of beauty in their own persons, of satisfying their passions, of feeling and thinking.’ Baudelaire had many followers among the French Decadents and Symbolists whom d’Annunzio was reading greedily – Théophile Gautier, Henri Régnier, Stéphane Mallarmé. In 1882, d’Annunzio’s first year in Rome, Walter Pater, whom d’Annunzio had read with Nencioni, visited the city for the first time, subsequently writing Marius the Epicurean, a novel in which homoerotic fantasy entwines itself around philosophical musings. Meanwhile Oscar Wilde, who called Pater’s essays ‘the holy writ of beauty’, was touring the United States. There Wilde, in velvet frock coat and satin breeches, lectured on the ‘House Beautiful’, not so much a style of interior decoration as an aspiration closely parallel to the d’Annunzian injunction that a life must be made in the same way as a work of art.

That beautiful life was at once ancient and modern. ‘All the literature of the present day is abject rubbish,’ wrote Giosuè Carducci. ‘Let us return then to true art, to the Greeks and the Latins. What ridiculous little dwarfs are these Italian realists!’ D’Annunzio had been one of those dwarfs, but the poems written during the first year and a half of his marriage, which would be published under the collective titles of La Chimera (pseudo-classical) and Isaotta Guttadauro (pseudo-mediaeval), are newly written examples of centuries-old verse-forms. Their words are archaic, their imagery (lilies, pomegranates, ailing damozels) is pre-Raphaelite. Their rhyme-schemes are tight, their rhythms song-like. Jewels and flowers heavy with erotic symbolism are disposed around the figures of noble maidens and their knightly suitors. Even the spelling is pseudo-antique. Soon after the publication of Isaotta Guttadauro a parody appeared, entitled Risaotto al Pomidauro (tomato risotto – spelt in an equally faked-up olde-worlde manner).

Scarfoglio had published the parody. D’Annunzio, ostensibly deeply offended, challenged him to a duel, which took place without injury to either party. It was widely suspected that (like the spat with Sommaruga over the ‘obscene’ jacket illustration) the parody, challenge and duel had been got up between the two friends as a way of drawing attention to the poems.

ELITISM

IN SEPTEMBER 1885, d’Annunzio quarrelled with a journalist, Carlo Magnico, and challenged him to a duel. At school d’Annunzio had been a prize-winning fencer. In Rome he had kept himself in training, but Magnico, who had the advantage of being considerably taller, bested him. D’Annunzio received a wound to the head, only a shallow cut, but it rattled him. (Pleasure’s hero comes close to being killed in a duel.) The writer and editor Mathilde Serao was present at the fight. She relates that the doctor, alarmed by the amount of blood d’Annunzio was losing, poured iron perchlorate over the wound. The bleeding was staunched, but the chemical did irreparable damage to d’Annunzio’s hair follicles – or so Serao, perhaps prompted by d’Annunzio, maintained. Soon afterwards he was bald.

The story, which has been repeated by all d’Annunzio’s biographers, doesn’t stand up. Photographs of d’Annunzio show no noticeable scar on his bald pate. What they do show is his hair receding gradually and along the usual lines. He goes bald just as other men go bald. But d’Annunzio did not want to be as other men. He had been proud of his ‘forest of curls’. The beginning of the end of his life as an ‘ephebe’ (a favourite word of his) was painful, and required transformation. The banal misfortune of losing his hair was reimagined as a battle wound. No longer an androgynous sprite, he began to construct a new persona for himself, that of the virile hero.

Many Italians were looking for such a hero, an autocratic Great Man. Italy’s parliamentary democracy was (as it has remained) desperately unstable: in its first forty years it saw thirty-five different administrations. In the 1860s, the first decade of its existence, it was stained by a scandal surrounding a manifestly corrupt deal over the tobacco monopoly. By 1873 one of its members described parliament as ‘a sordid pigsty, where the most honest men lose all sense of decency and shame’.

The aristocrats who had previously had a monopoly of power despised parliament as a talking shop for the vulgar. Politicians on the left complained that its members represented no one but the wealthy. Elections were all too obviously rigged. Even where the ballot boxes were untampered with, few votes were truly free. Initially the electorate was tiny, and successive reform bills extending the franchise only served to shore up the forces of reaction. The lower down the social scale the voter, the more likely he was to vote docilely as his priest or his landlord instructed him. In the countryside the new democracy looked much like mediaeval feudalism. British historian Christopher Duggan sums up: ‘Bribery of all sorts was commonplace – money, food, offers of jobs, loans – and in many parts of the south men with a reputation for violence – bandits, or mafiosi – were widely deployed to intimidate voters. Election days were frequently turned into carnival occasions with landowners marching their supporters, as if they were a feudal army, off to the polling stations accompanied by musicians, priests and dignitaries.’ Those few ‘new men’ who attained a seat in parliament were perceived (largely correctly) as being as self-serving as their predecessors, and ill-educated to boot.

In 1882, a few months after d’Annunzio’s arrival in Rome, Giuseppe Garibaldi died. Garibaldi had been extremely troublesome to Italy’s government up to the end of his life but, dead, he became its totem. Francesco Crispi, who had been one of his lieutenants, announced, paraphrasing Carlyle, that ‘in certain periods of history … Providence causes an exceptional being to arise in the world … His marvellous exploits capture the imagination, and the masses regard him as superhuman.’ Garibaldi was such a being. ‘There was something divine in the life of this man.’

In his lifetime Garibaldi had proposed that he should be made a ‘dictator’. The word was a long-unused Latin title, which had yet to acquire the fell associations it now has, meaning one granted extraordinary powers for a limited period at a time of national crisis. On occasion, explained Garibaldi, he had wished for such powers as, in his time as a seaman, he had sometimes seized the ship’s helm, knowing he was the only man on board who could steer it through a storm. In the Italy he had helped bring into being there were many who, disenchanted with the corruption and incompetence of their parliamentarians, longed for just such a ‘dictator’. ‘Today Italy is like a ship in a mighty storm,’ wrote a political commentator in 1876. ‘Where is the pilot? I cannot see one.’

D’Annunzio read Darwin while he was still at school, and quickly grasped the salient point that evolution was a continuing process. It followed that, in any generation, there will be some individuals who are more highly evolved than others. Men (and women) were not, in d’Annunzio’s view, born equal. As Pleasure’s Andrea Sperelli passes from palace to palace he is depressed by the sight of workers in the streets. Some are injured or sick. Others are swaggering arm in arm, singing lewd songs. They are jarring reminders that, outside the warm, scented drawing rooms in which the god-like aristos indulge themselves, swarm the lesser kind of humans, most of them ‘bestial’.

D’Annunzio wrote to a composer friend: ‘Make much of yourself, for God’s sake! … Don’t be afraid of the fight: it is Darwin’s struggle for life [d’Annunzio’s English], the inevitable, inexorable struggle. Down with him who concedes defeat. Down with the humble!’ His friend should not be scandalised by these ‘unchristian maxims’, he goes on. Altruism and humility must be laid aside. ‘Listen to me … I have much experience of fighting furiously with my elbows.’ He is aggressive and competitive and proud of it. D’Annunzio had yet to read Nietzsche but already he was thinking along Nietzschean lines. ‘The reign of the nonentity is finished. The violent ones rise up.’

MARTYRDOM

WHEN I MARRIED MY HUSBAND,’ the Duchessina Maria said once, ‘I thought I was marrying poetry. I would have done better to buy, for three and a half lire, each of his volumes of verse.’

Their idyll was short-lived. Shortly after d’Annunzio brought his wife and baby back to Rome he began an affair with a fellow journalist, Olga Ossani, who wrote for the Capitan Fracassa under the name of Febea. Olga had, according to her new lover, the head of Praxiteles’ Hermes. D’Annunzio was pleased by her ‘strange bloodless face’ and her prematurely white hair. She was clever and unconventional: it was by no means common for a woman to write for the press. He described her at a press ball in the month their liaison began, stretched out on a sofa, laughing and exchanging witty ‘little impertinences’ with the gentlemen besieging her.

D’Annunzio was attracted to independent-minded women. He liked to try out his ideas on them, inserting into his love letters extended passages of prose which would reappear in his essays or novels. He wanted them to be discriminating readers, and to be capable of entertaining him. He had called Elda ‘child’ (which, given her age when they met, was almost literally descriptive), but he didn’t usually choose infantile partners. Olga Ossani, a few years older than d’Annunzio, was one of a line of mature, talented women who were to become his lovers.

They used to meet in a room rented for the purpose (a reckless extravagance for a man who could barely pay for his main home) which he decorated with Japanese screens and swathed with green silk. Or they would walk in the gardens of the sixteenth-century Villa Medici (then and now the French Academy of Rome). Henry James called the villa’s mannerist gardens ‘the most enchanting in Rome’. James loved the wooded hill which rises above the formal parterres. ‘The Boschetto has an incredible, impossible charm … a little dusky forest of evergreen oaks. Such a dim light as of a fabled, haunted place, such a soft suffusion of tender grey-green tones.’ One day, after a bout of love-making during which Ossani had covered him with ‘the bites of a vampire’, d’Annunzio left their room with his body ‘as spotted as a panther’. The following evening they met again in the Villa Medici’s ‘dusky forest’. ‘Sudden fancy. The moon was shining through the holm oaks. I hid. I took off my light summer suit. I called her, leaning against an oleander, posing as though I was tied to it. The moon bathed my naked body, and all the bruises were visible.’

A fashionable parlour game of the period was that of tableaux vivants: players dressed up (often very elaborately) and posed as historical or legendary characters. Other party guests were required to identify them. Olga guessed d’Annunzio’s conundrum at once. ‘“Saint Sebastian!” she cried.’ As she embraced him, he felt, with a delicious shudder, that invisible arrows were thrust through his wounds and fixed into the tree behind.

Soon after that night, d’Annunzio wrote to Olga, signing himself ‘St Sebastian’, and urging her to read Salammbô, Flaubert’s novel set in ancient Carthage, in which a physically splendid Libyan warrior allows himself to be tortured to death for love of a priestess, and in which scores of human victims are sacrificed to a pitiless god. ‘Your exquisite intellect will derive from this reading one of the most extended and profound of voluptuous pleasures,’ he told her.

The association of pain with pleasure was a commonplace of late nineteenth-century art and literature, and it often manifested itself in biblical stories or legends of the saints. Flaubert wrote about the self-inflicted tortures endured by Christian saints. ‘Thou hast conquered, O pale Galilean!’ wrote Swinburne, ‘the world has grown grey from Thy breath,’ but Swinburne’s poetry, like d’Annunzio’s, is replete with religious imagery. Oscar Wilde (like Flaubert before him) would soon be writing a jewelled and sadistic version of the story of Salome and John the Baptist. Biblical themes provided both an oriental setting and an antique grandeur, combining the two exoticisms of place and time, and the cult of the martyrs added to the mix the intoxicating stench of blood.

St Sebastian is a sexually suggestive martyr. Vasari tells us that a painting of him by Fra Bartolommeo had to be removed from its altar because it ‘sparked lascivious desire’ in women who saw it. Nearly three centuries later, Stendhal reported that the problem hadn’t gone away. Guido Reni’s paintings of St Sebastian (of which there are several) had been taken down because ‘pious women kept falling in love with them’.

Sebastian was a Roman officer at the beginning of the fourth century, condemned to death for his Christian beliefs. The Golden Legend, the thirteenth-century compendium of saints’ lives, relates that he was shot full of arrows and left for dead. He revived and returned to the imperial palace in the hope that his miraculous escape would convince the co-emperors, Diocletian and Maximianus, of Christ’s divine power. The emperors remained obdurate. Sebastian was condemned a second time. He was beaten to death and his body thrown into the main sewer.

In early representations he is a mature, bearded man, fatherly and fully dressed as befits an officer. But by the fourteenth century it had become conventional for painters to depict him as a beautiful youth stripped bare. In the 1370s, Giovanni del Biondo showed him hoisted on a stake, nude but for a loincloth, in a pose which invites comparison with Christ’s crucifixion, and so bristling with arrow shafts he looks – as an early iconographer remarked – ‘like a hedgehog’. Subsequent depictions are more graceful, more erotic. Piero della Francesca, Antonello da Messina, Mantegna, Guido Reni and numerous others have him standing or leaning, head falling back as though in an ecstasy of pain, his beautiful nearly naked body cruelly pierced.

Arrows are associated with Cupid. To be struck by them is to be inflamed by sexual passion. When d’Annunzio and Olga had their tryst in the Villa Medici gardens, Sigmund Freud had yet to begin studying nervous disorders, but d’Annunzio would not have needed psychoanalytic theory to point out to him that the vision of a physically perfect youth helplessly exposed to penetration by his tormentors’ shafts is a potent image of ravishment.

D’Annunzio shared his preoccupation with the saint with a number of his celebrated contemporaries: writers Marcel Proust, Thomas Mann, Oscar Wilde (who assumed the name Sebastian after his release from prison) and the photographer Frederick Holland Day. These men, and subsequent Sebastianophiles Yukio Mishima (whose ideas and life story in many ways reflect d’Annunzio’s), film-maker Derek Jarman, and the photographers Pierre et Gilles, were all, at least to some extent, homosexual. Magnus Hirschfeld, the pioneering German sexologist and contemporary of d’Annunzio, identified pictures of St Sebastian as being among the images in which an ‘invert’ would take special delight. D’Annunzio’s Sebastian cult raises unavoidable questions about his sexual orientation.