The Prince Who Would Be King: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © Sarah Fraser 2017

Cover image shows detail from Henry, Prince of Wales with Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex in the Hunting Field c. 1605 by Robert Peake (active 1580–1635) Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

Sarah Fraser asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

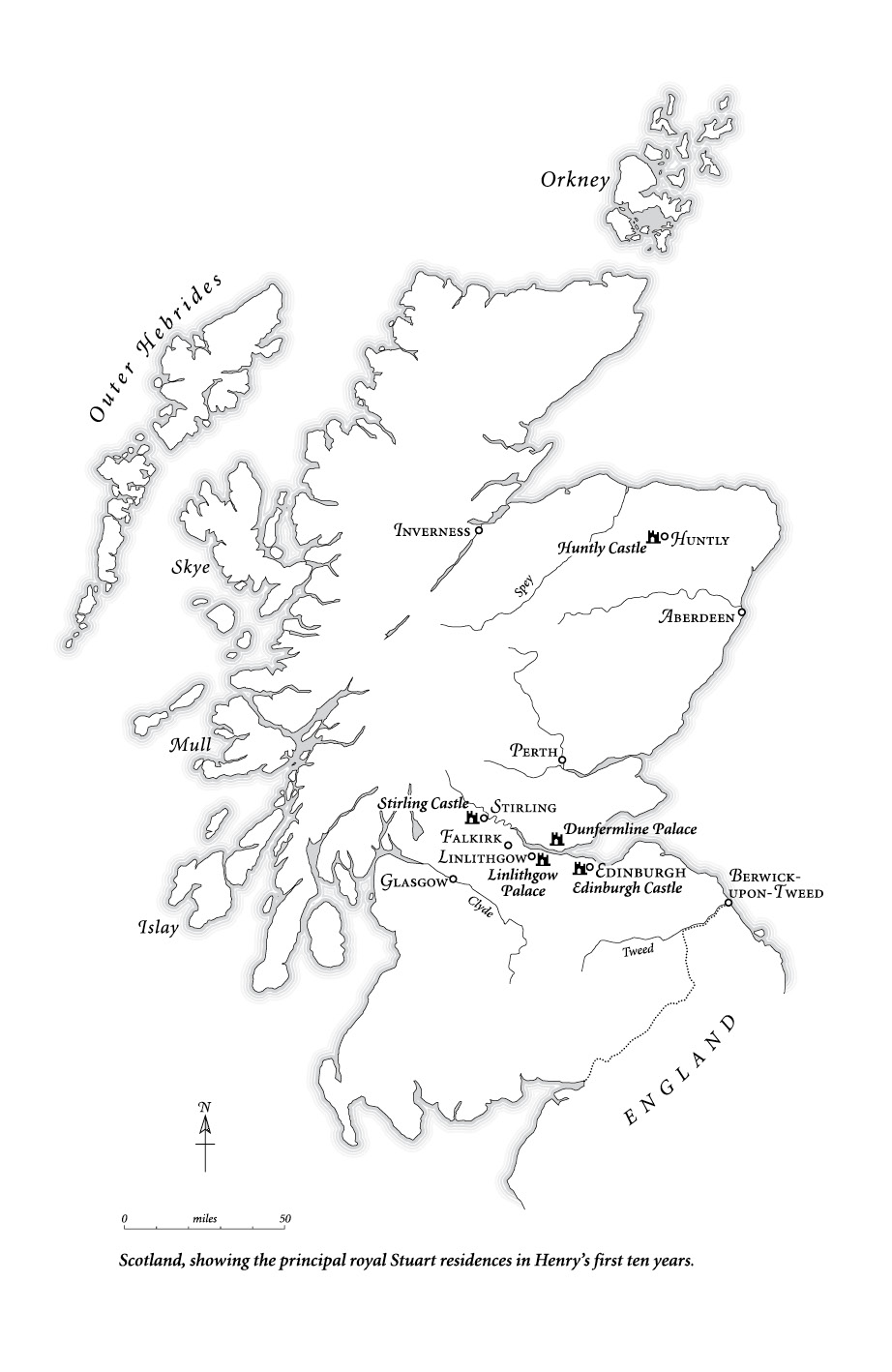

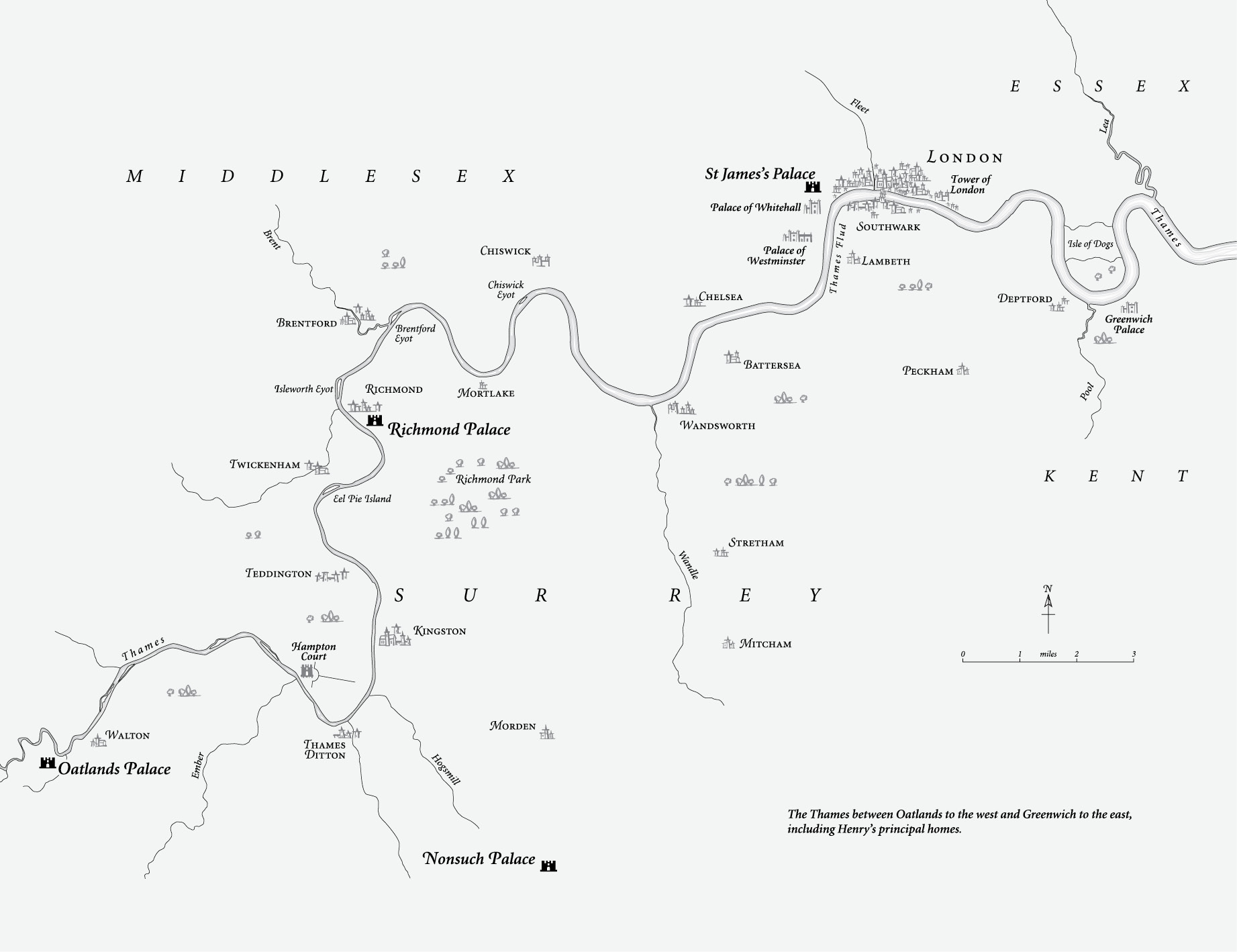

Maps by Martin Brown

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007548101

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780007548095

Version: 2018-02-13

DEDICATION

For my sons, Sandy and Calum

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

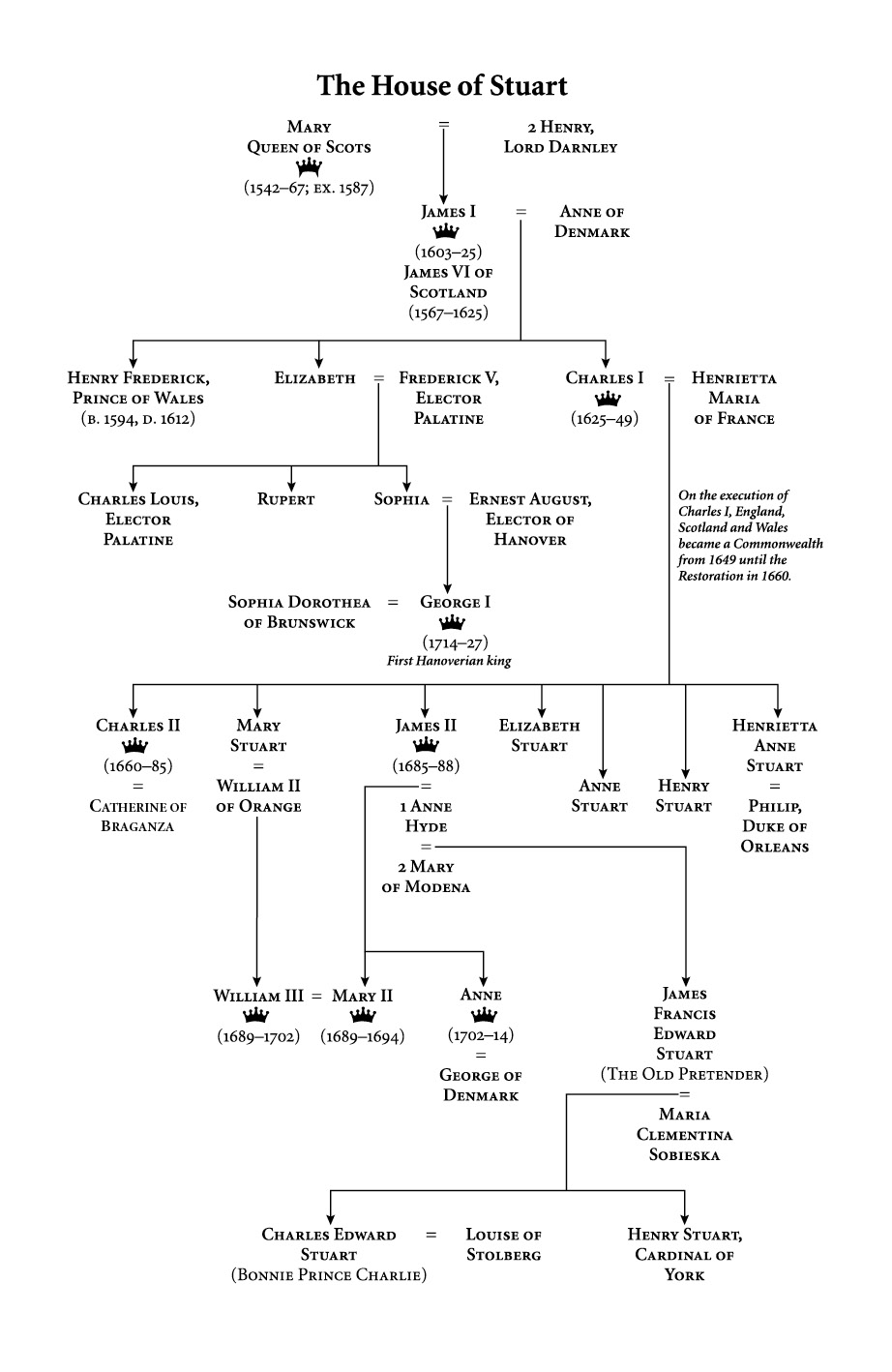

House of Stuart Family Tree

Maps

Conventions and Style

Preface: Effigy

PART ONE: SCOTLAND, 1954–1603

1 Birth, Parents, Crisis: ‘A son of goodly hability and expectation’

2 Launching a European Prince

3 The Fight for Henry: ‘Two mighty factions’

4 Nursery to Schoolroom: ‘The King’s Gift’

5 Tutors and Mentors: ‘Study to rule’

PART TWO: ENGLAND, 1604–10

6 The Stuarts Inaugurate the New Age

7 A Home for Henry and Elizabeth: Oatlands

8 The Stuarts Enter London: ‘We are all players’

9 Henry’s Anglo-Scottish Family: Nonsuch

10 Henry’s Day: ‘The education of a Christian prince’

11 Union and Disunion: ‘Blow you Scotch beggars back to your native mountains’

12 Europe Assesses Henry: ‘A prince who promises very much’

13 The Collegiate Court of St James’s

14 Money and Empire: ‘O brave new world’

15 Friends as Tourists and Spies: ‘Traveller for the English wits’

16 Henry’s Political Philosophy: ‘Most powerful is he who has himself in his own power’

17 Favourites: ‘The moths and mice of court’

18 Henry’s Supper Tables: Lumley’s library and tavern wits

19 Henry’s Foreign Policy: ‘Talk for peace, prepare for war’

20 Heir of Virginia: ‘There is a world elsewhere’

PART THREE: PRINCE OF WALES, 1610–12

21 Epiphany: ‘To fight their Saviour’s battles’

22 Prince of Wales: ‘Every man rejoicing and praising God’

23 Henry’s Men Go to War: Jülich-Cleves

24 Henry Plays the King’s Part: King of the Underworld

25 From Courtly College to Royal Court

26 Court Cormorants: Henry and the king’s coterie

27 The Humour of Henry’s Court: Coryate’s Crudities

28 Marital Diplomacy: ‘Two religions should never lie in his bed’

29 Supreme Protector: The Northwest Passage Company

30 Selling Henry to the Highest Bidder: ‘The god of money has stolen Love’s ensigns’

31 A Model Army: ‘His fame shall strike the Starres’

32 End of an Era: ‘My audit is made’

33 Wedding Parties: ‘Let British strength be added to the German’

34 Henry Loses Time: ‘I would say somewhat, but I cannot utter it!’

35 Unravelling: After 6 November 1612

36 Endgame

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Picture Section

Illustration Credits

Index

By the Same Author

About the Author

About the Publisher

CONVENTIONS AND STYLE

Spelling and punctuation, unstable in this period, are modernised to assist comprehension, and to prevent interruption of the narrative by lexical curiosities that might catch the eye and distract from the narrative flow. Even James VI and I revised his Basilikon Doron for publication to ease readability.

Contractions are expanded (thus mistie becomes Majesty). The spelling of proper names has been standardised. For example, Henry also spelled his name ‘Henrie’, but I have opted here for Henry. Individuals born with several titles, or those who changed name on receipt of them, can be a particular problem for the biographer writing for a non-specialist audience. Cecil was not the monolith ‘Salisbury’ when James VI negotiated in treasonable secrecy with Secretary Robert Cecil to inherit Elizabeth’s thrones. I note in media res when an important change has taken place and from then on, I use the new name. With regard to place names, ‘Great Britain’ as a term for the multiple Stuart territories is a bit of an anachronism, but I use it as it is so apposite. Place names are modernised and standardised (thus Finchingbrooke becomes Hinchingbrooke).

For dates, the year begins on 1 January not 25 March (as it did on this side of the Channel).

British currency was in pounds, shillings and pence: £ s. d. One English pound was worth £12 Scots. To understand what a particular amount would represent today you can add two zeros to the figure, to get a rough approximation.

PREFACE

Effigy

‘How much music you can still make with what remains’

– ITZHAK PERLMAN

In the conservation room at Westminster Abbey lies the wreck of a life-sized wooden manikin, stretched out on a white table. This is what remains of Henry Frederick Stuart, Prince of Wales.

Recalling a cast of the nameless dead at Pompeii, the figure’s mute appeal touched me. Its ruined state tells of Henry’s importance, but also what happened to his legacy. After Henry died, visitors ransacked this likeness for relics – someone even stole his head. His effigy was unique in 1612. Up until then, they were made to honour monarchs and their consorts, not their offspring.

Who was Henry Stuart, to earn this effigy, and the state funeral that went with it – itself unprecedented in England, in scale and magnificence?

This book sets out to recreate Henry, an important but almost forgotten piece of history’s puzzle. Restoring Henry in his time and place reveals paths running through his court, from Elizabeth I to the Civil War, to a Puritan republic, and the British Empire in America; but also, to the transformation of the navy into a force achieving global domination of the high seas, and the breaking down and recreation of Britain’s armed forces into a world-class fighting machine.

Henry re-founded the Royal Library, amassing the biggest private collection in England. He began to create a royal art collection of European breadth – paintings, coins, jewellery and gem stones, sculpture, both new and antique, on a scale no royal had attempted before. These went on to become world-class collections under his brother, Charles I, and form the backbone of the British Library and the Queen’s Royal Collection today. Henry began the grandest renovations of royal palaces in his father King James VI and I’s reign, and mounted operatic, highly politicised masques. His court maintained a dozen artists, musicians, writers and composers. Ben Jonson, Michael Drayton, George Chapman and Inigo Jones all created work for him. He responded with enthusiasm to the vogue for scientific research, putting time, money and men into buying state-of-the-art scientific instruments – telescopes and automata that tried to model the heavens. He financed ‘projects’ – business schemes – to try and extract silver from lead, and make furnaces more fuel efficient.

Henry and his circle’s curiosity and ambition reflected the era’s desire to sail through the barriers of the known world. He persuaded his father the king to let him begin a full-scale review and modernisation of Britain’s naval and military capacity. He was raised in the ancient culture of chivalry, but welcomed active servicemen from the front line of Europe’s religious wars. Henry’s court was where the latest developments in the art of warfare were received and developed. He became patron of the Northwest Passage Company, established to find a sea route across the top of America and open up the lucrative oriental trade to British merchants. He and his court were important promoters of the project to realise the decades-long dream of planting the British race permanently in American soil. Whatever we think of colonialisation now, such men transformed the world.

As a man and prince, Henry saw himself to be European as much as British, using as one of his mottoes the expansionist ‘Fas est aliorum quaerere regna’, ‘It is right to ask for the kingdoms of others’. At his death aged eighteen, he was preparing to go and stake his claim to be the next leader of Protestant Christendom in the struggle to resist a resurgent militant Catholicism. He was a devout, Puritan-minded Protestant. In the arena of politics, there is a case for seeing Henry’s court as a significant waystation between the abortive aristocratic uprising in 1601 – when the 2nd Earl of Essex sought to force Queen Elizabeth to name James VI of Scotland as her heir in Parliament – and the regicides who shivered in the Palace of Westminster’s Painted Chamber, ready to sign the death warrant of Henry’s little brother, Charles I, in January 1649. By the time of Henry’s death, you could see the prince and his court positioning themselves at the front line of so much that came to define Britain in its heyday.

I am aware that when I say, Henry did this, and Henry did that, one question arises at once. Who was Henry?

Henry was a son, brother, friend, master, patron. ‘Henry’ was the crown prince. The inverted commas around his name allude to the medieval idea of the king’s two bodies – ordinary man and the monarchy, the Crown. The natural man decayed and died. The Crown merely suffered a demise and passed to the next bearer. Crown Prince Henry possessed a physical body and a body politic. He was a boy and the crowns united: the first Prince of Wales born to inherit the united kingdoms of Britain.

His legacy stretched beyond his death to the conflagration coming in 1618. The Thirty Years’ War would be the longest, bloodiest conflict in European history until the First World War in 1914. It tore Europe apart, and Henry had been determined to drag England towards involvement in it. What did that imply about his character?

He was only nine when he came to England. For nearly a decade in Scotland and nearly a decade in England some of the most influential men, and women, of the Jacobean age wanted to shape the character of the future king and his monarchy. Who he responded to, and to whom he did not, suggests what kind of king he would have made.

His effigy remains as a symbol of his dual nature. As his teenage body rotted in its coffin, his icon was supposed to live for ever. The eager ravages the effigy suffered reflect how well Henry had grown into his public role. By 1612, his court was recognised as an important power bloc at home and abroad. For me, he is the greatest Prince of Wales we ever had.

A recent straw poll shows how far Henry has dropped out of the national memory. In 2012 the National Portrait Gallery in London staged an exhibition devoted to him. It introduced what one reviewer after another called this ‘forgotten prince’ to a wider audience. The faceless anonymity of his effigy now symbolises his disappearance. Many people do not realise his brother Charles was never born to be king – nor how bright a star Henry rose to be in the Jacobean and European firmament. This biography is driven by a passionate desire to change that.

As I set out on my researches, Westminster Abbey began work to create new galleries to house its unique collection of effigies, including what remains of Henry’s. This book is my contribution to the restoration of Henry, Prince of Wales – from forlorn worm-eaten object in a backroom, to an iconic, colourful character standing tall in his time and place, on the stage of British history.

PART ONE

Scotland

1594–1603

ONE

Birth, Parents, Crisis

‘A SON OF GOODLY HABILITY AND EXPECTATION’

Dawn, Tuesday, 19 February 1594. The herald left his fire, shivered up the stone steps and strode out onto the walls of Stirling Castle to announce the great news. For four years Scotland had waited for a child, a male heir, to secure the throne. At last the king ‘was blessed with a son of goodly hability and expectation’. Prince Henry Frederick Stuart’s birth gave ‘great comfort and matter of joy to the whole people’. The entire day cannonades ricocheted across the country. Scots of all ranks danced in the light of huge bonfires, as ‘if the people had been daft for mirth’.

The proud father, James VI, despatched messengers to his fellow princes of Christendom, the first sent galloping south to London. Henry was James’s gift to his childless cousin, the ageing, putative virgin queen, Elizabeth Tudor of England. The gift he expected in return was nothing less than her thrones and dominions. A prince had been born to embody the kingdoms united for the first time in history. If Elizabeth would name James VI of Scotland and the future King Henry IX her heirs, the boy could secure England’s as well as Scotland’s future.

Throughout the celebrations, Henry’s mother, Anne of Denmark,* had remained lodged in the birthing chamber at Stirling Castle.

Landing at Leith four years earlier, fifteen-year-old Anne had made a sensational entrance: pale-skinned, reddish blonde hair, notably attractive, she rode through Edinburgh, her new husband at her side showing off his queen. Behind them the king’s oldest friends, the Mars of Stirling Castle, followed stony-faced. From the side of the highway, a flock of black-clad ministers of the Scottish Calvinist kirk eyed the daughter of Denmark – her ‘peach and parrot-coloured damask’ dress, her ‘fishboned skirts lined with wreaths of pillows round the hips’; their gaze travelling across her liveried servants, horses and silver coach – and shuddered.

In England these hard-liners – or ‘purer’ Protestants, as they saw themselves – were derided as ‘Puritans’. They called themselves the godly. Soon enough, Christian duty would compel them to open their pursed lips to censure Queen Anne and her circle for their erratic attendance at interminable sermons on sin and corruption. God made them denounce the young queen’s ‘lack of devotion to the Word and Sacrements’, and love of ‘waking and balling’ – staying up late to dance and gamble. She filled her evenings with music and elaborate court entertainments. One radical Calvinist griped that all royals were ‘the devil’s bairns’, so what could you expect? (James responded by exiling him.) The idea of Anne as utterly frivolous would prove remarkably enduring.

Anne knew herself more than equal to them. Her brother, Christian IV, ruled Denmark – the Jutland Peninsula and the islands around it. His influence extended over Norway and east across what is modern-day Sweden, Gotland and the Baltic island of Bornholm. He also ruled Iceland and Greenland. To the south, Denmark controlled the German duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. Holstein lay within the borders of the Habsburg-dominated Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. So, one branch of the house of Oldenburg, Anne’s family, were also imperial princes, owing allegiance to the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna. This involved the Danes in German and imperial affairs. Off the north coast of Scotland itself, Denmark claimed the Orkneys and owned the Faroe Islands.

Anne grew up a royal princess of one of the largest Protestant political entities in Europe. Her grandfather, Christian III, converted Denmark to Lutheranism in 1536, but Denmark declined to adopt the ‘purer’ form of Protestantism – the Calvinism that Scotland came to profess under John Knox. Anne’s former suitor, Prince Maurice of Nassau, withdrew his offer on hearing that she would not convert to Calvinism in order to marry him.

Denmark’s location gave it control of the sea lanes connecting the Atlantic to the Baltic. The tolls it charged shipping to pass through the Danish Sound and trade with the Hanseatic ports, made its monarchy wealthy. When Christian IV finished modernising it, Denmark boasted ‘the largest and most efficient naval force in northern Europe’. His new nephew, Prince Henry, would grow up to cherish an equal passion for his navy.

The Danes spent as befitted Renaissance Protestant princes. Their riches and power financed cultural activity that put them at the forefront of the Renaissance. Christian’s huge architectural projects changed the face of Copenhagen, making it one of the loveliest cities in Europe. Anne and Christian’s mother, Sophie of Mecklenburg, maintained Tycho Brahe, the first astronomer in Europe to win international fame. Scholars flocked from across the Continent to meet him. Visitors to Brahe’s island home included James VI when he came to collect Anne, his betrothed, in October 1589. James passed with amazement and delight through rooms full of books, maps and spheres to help man uncover the laws of nature by which God moved the heavens. Laboratories bubbled and steamed with alchemical scientific experiments. Brahe set on his own printing press his groundbreaking book on astronomy, the foundation text for Kepler and Galileo.

Buildings and gardens, statuary and art works, developments in all branches of science, new political theory and historical awareness, were all part of that international lingua franca of the Renaissance. It was a language Anne grew up speaking as a native and passed on to all her children. Anne of Denmark was, in every way, a brilliant match for James VI of Scotland. A princess raised in this milieu; a woman who was bilingual in Danish and German; who had enough French to be able to write and converse with her new husband (who had no German); who then quickly learned Scots to a high level of idiomatic ease; who enjoyed and patronised a broad range of cultural activity, was unlikely to be the empty-headed fool of hard-line Calvinist censure.

In addition, the Scottish court soon discovered their queen possessed a strong will. Shortly after she arrived in Scotland in 1590, Anne dismissed James’s most important female attendant from her service, sixty-five-year-old Lady Annabella Murray, Dowager Countess of Mar. The king’s love and respect for ‘Lady Minnie’ ran deep. The Mars were hereditary keepers of Stirling Castle and, by tradition, the guardians of Scottish monarchs. King James had been fostered out to them when he was an infant and Lady Minnie was the only mother he knew. The king grew up with her son, Master John Erskine, whom he nicknamed Jocky o’ Sclaittis (Slates), in fond recollection of schooldays spent together.

Anne, though, discovered Lady Minnie gossiping with her friend, the wife of the Scottish chancellor: the devout old dowager regretted too loud that James had not married the more suitable Catherine, sister of French Huguenot leader, Henri of Navarre. Out both women went. In their place Queen Anne brought in her Danish friends and lively young Scots women, including the Ruthven sisters, Beatrix and Barbara, and Henrietta Stuart, Countess of Huntly. Henrietta was the Catholic wife of a Catholic earl – pure gall for the godly who believed the queen’s court was being peopled with the weak and the wicked: Lutherans and papists.

Four years later, in February 1594, Anne understood very clearly the huge political and dynastic significance of her son’s arrival. From the birthing chamber, a lady-in-waiting carried the baby to its royal nursery within the Prince’s Tower. They swaddled him and he latched onto the dugs of Margaret Mastertoun, his mistress nurse. When he gurned, Mistress Mastertoun handed Henry to one of his four rockers.

Good medical practice prescribed swaddling to keep Henry’s limbs straight, prevent rickets, and ensure strong growth. A few months later, liberated from the torment of swaddling bands, Henry started to stretch and move, but not crawl. Crawling suggested a prince too close to his animal nature, with its connotation of original and other sins. God condemned the serpent to crawl on his belly and eat dust all his days – not the crown prince. As soon as the infant could hold himself upright, Henry’s nursery maids strapped him into a wheeled and velvet-lined baby walker.

To keep him alive, four medical practitioners attended in rotation: Dr Martin, Gilbert Primrose the surgeon, Dr Gilbert Moncrieff, and Alexander Barclay, Henry’s apothecary. Infant mortality in the under twos ran at up to fifty per cent, giving a royal mother good reason to stay close and supervise. Queen Anne meant to preside over her son’s nursery, to oversee his infant japes and woes. By birth and upbringing a political animal, Anne also wanted to instil in Henry her religious, political and cultural values, not an enemy’s; and enemies, in the queen’s view, lived too close to her boy.

Anne had been horrified when James commanded her to leave her own palace and go to the Mar stronghold at Stirling to give birth. As soon as it was clear that the baby would live, the king followed Scottish royal custom. Within forty-eight hours of his safe delivery, Prince Henry was fostered out to the Earl of Mar and that ‘venerable and noble matron’ Lady Minnie. The king formally contracted Mar not to deliver the prince ‘out of your hands except [if] I command you with my own mouth, and being in such company as I myself shall like best of.