The Ravenmaster: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London

Unlike my relationship with Munin, Merlina and I are close. Very close. Indeed – after many years – she has bonded with me and two of my assistants and is always very friendly towards us. She is not, however, friendly towards anybody else – including our fellow Yeoman Warders.

Over the past few years Merlina has become quite a celebrity. She has her own dedicated followers on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. She receives gifts and cards and letters from well-wishers and has appeared countless times on television and in newspaper and magazine articles. She likes playing with sticks while rolling on her back, doing forward rolls, calling out to the crows to come and play with her, stealing stuff from unsuspecting members of the public, playing in the snow, playing dead, drinking water out of the fountain, washing crisps if she doesn’t like the flavour, emptying the bins on the endless hunt for food, hunting mice, and stalking pigeons.

Merlina could fly off to a new life if she so desired, but due to the nature of our bonding, and with a bit of careful flight-feather trimming, we’ve managed to keep her here at the Tower. She is our most free-spirited bird; she’s also my closest friend among the ravens.

In many ways, Merlina is a bit of a loner: she refuses to socialise with any of the other ravens. I think of her as the Tower Princess. If another raven goes anywhere near her, she hops along to find me to seek my protection, often bringing me little treats to share, usually rotten meat or rats’ tails. Her favourite activity is to sit with me in the Bloody Tower sentry box and fall asleep while I gently stroke her feathers. Whatever you do, do not try this if you visit her. Not if you value your fingers.

Erin

Female

Entered Tower service 2006

Current age: Twelve (age on arrival: six weeks)

Place of origin: Yatton, Somerset

Presented by Mr Martin Harris

Named by Ravenmaster Derrick Coyle

It’s said that ravens mate for life, but in my experience Raven Erin’s partnership with Raven Rocky is a rather more complex process than is often assumed by us humans. What I can say is that Erin and Rocky like to perch together, fly together, walk together, and preen together. They’re a classic couple in many ways – and in this partnership, it is Erin who most definitely wears the trousers.

Erin may be one of our smallest ravens, but she is by far the noisiest. She likes nothing better first thing in the morning than craawing and cronking at the top of her voice and annoying the residents of the Tower. She’s not, shall we say, a bird who is backward in coming forward. She will chat away forever, is extremely boisterous, and loves to pester the other ravens. One of her favourite games is to invade another bird’s territory, pick a fight, cause all sorts of commotion, and then suddenly back off. With Erin, I often find myself having to assume the role of policeman. If she’s on Tower Green, for example, squawking at Merlina, I’ll intervene with a wag of my finger, tell her to move along, and then off she goes.

Erin and I are not exactly close, but we get along fine. We have a few volunteers at the Tower who like to assist with our work with the birds, and over the years Erin has befriended one or two of them, whom she graciously allows to feed her the occasional nut or biscuit.

Many of our American visitors like to point out that the name Erin is Irish, though I like to point out in return that it is in fact a Hiberno-English derivative of the Irish word ‘Éirinn’, meaning Ireland, and no, she’s not from Ireland. She’s from Somerset. The naming of the ravens can sometimes seem nonsensical – and indeed paradoxical and ironic, as is the case with Erin’s partner, the wonderfully though inappropriately named Rocky.

Rocky

Male

Entered Tower service July 2011

Current age: Ten (age on arrival: three)

Place of origin: Yatton, Somerset

Presented by Mr Martin Harris

Named by Ravenmaster Chris Skaife

Traditionally our ravens were named after the person who presented them to the Tower. Thus, Raven Edward, who was presented to the Tower around 1890 and who was named after Colonel Edward Treffry from the Honourable Artillery Company. Or one of my favourites, the legendary Raven Edgar Sopper, presented in 1923 and named after Colonel Sopper. All of our ravens these days are bred outside the Tower by a small number of recognised breeders, and acquired by the Tower as and when we need them, so our naming practices have had to change. We once had a Ronald Raven, for example, so named by viewers of the children’s television programme Blue Peter. We’ve had ravens named Cedric, Sandy, Mabel, Pauline, and – in tribute to the character played by Tony Robinson in the TV comedy Blackadder – Baldrick.

Rocky is in fact named after the former Ravenmaster, Rocky Stones, and not after the boxer played by Sylvester Stallone, which is probably for the best because Rocky is most definitely not a fighter. Admittedly he does have a distinctive short fat beak, which makes him look a bit as if he has a broken nose and is about to land a heavy punch on you. He’s big and he likes to swagger around, and he does his best to protect Erin when she gets into trouble, but he’s really a very shy, sweet-natured sort of a bird. In fact, he’s a bit of a softy. He follows Erin around like a little puppy, is completely uninterested in me or in the public, and likes nothing more than to spend his time snuggling up to her, though how on earth he puts up with her incessant squawking I have absolutely no idea.

Jubilee II

Male

Entered Tower service May 2013

Current age: Five (age on arrival: six weeks)

Place of origin: Yatton, Somerset

Presented by Mr Martin Harris

Named Jubilee by popular demand

Jubilee II started out his life at the Tower as a stand-in. In 2012, in honour of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, the Tower authorities thought it might be a nice idea to give Her Majesty a raven as a present. We’d keep it here on her behalf and look after it for her. Shortly after presenting the bird, I went away on holiday to the United States. No sooner had my flight landed than I received a frantic phone call from one of my colleagues.

‘Chris, there’s a bit of a problem.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Two ravens have died.’

‘Which ravens?’

‘Jubilee and Gripp.’

‘Died?’

‘Killed.’

‘Foxes?’

‘Foxes.’

‘So you’re telling me I’ve just come all this way to the US on holiday and the Queen’s new raven has been killed by a fox?’

‘Yep. Sorry, mate.’

It was not a great start to my long-awaited holiday, but fortunately we were able to acquire two replacement ravens, whom we named Jubilee II and Gripp II.

Jubilee II is currently Munin’s partner. I say currently because when Munin dies I might try to pair Jubilee II with Merlina. Merlina has recently started to allow Jubilee II to spend a little time with her on Tower Green, which is very unusual. Merlina, as I have said, is not a bird who usually tolerates the company of other ravens. There’s a bit of an age difference between Merlina and Jubilee II, but they seem to get on, and I can certainly see why. Jubilee II is very much the strong, silent type: well-behaved, well-groomed. Perfect boyfriend material. I think of Jubilee as a knight of the Tower.

Gripp II

Male

Entered Tower service May 2013

Current age: Five (age on arrival: six weeks)

Place of origin: Yatton, Somerset

Presented by Mr Martin Harris

Named by Ravenmaster Chris Skaife

Gripp is the opposite of Jubilee: tiny and rather frail. We assume that Gripp is male – but I rather fancy that he is in fact a she. It wouldn’t be the first time that one of our male birds turned out to be female. As I have mentioned, Merlina started out life as Merlin, and there have doubtless been other examples of mistaken identity during the history of the Tower ravens. The sexing of birds is notoriously difficult, even for vets, never mind for Yeoman Warders. Ravens not only lack external sexual organs, like most species of birds, but the male and female are almost identical in appearance, and there are no great differences in behaviour. It’s not as if the males have brighter plumage or different feather patterns, or wattles or combs or crests or leg spurs that might help you distinguish them from females. To the untrained eye, the only noticeable difference is that the male ravens tend to have a slightly longer middle toe and a thicker bill; but then again, we’ve had female birds before with great thick bills, and measuring the difference in ravens’ toes is not a hobby for the faint-hearted. Handling the birds can make them extremely stressed at the best of times, so really the only way to determine Gripp’s sex would be to take a feather and have it DNA tested. Since Gripp seems perfectly happy as s/he is, and because we treat all the birds equally here at the Tower anyway, whatever their gender, there seems little point in putting him/her through the stress. So, for the moment Gripp remains a he – a rather timid and shy he, admittedly, who requires a little bit more looking after than some of the other birds. I have a bit of a soft spot for him, and don’t like to see him being picked on or bullied by the others.

Harris

Male

Entered Tower service May 2016

Current age: Two (age on arrival: six weeks)

Place of origin: Yatton, Somerset

Presented by Miss Lori Burchill

Named by Ravenmaster Assistant Shady Lane

Harris is the youngest and the biggest of our current birds. You can tell he’s young – if you can get close enough – because the inside of his mouth is pink. The raven mouth turns black as the bird ages, in much the same way as our hair turns grey. Harris will be counted as a juvenile for about three years before coming into full maturity, though he’s already started displaying signs of adult behaviour. Just a couple of weeks ago he spent three days up on the rooftops of the Tower, checking things out, only returning to be with the other ravens because he was hungry. I fancy he’s going to keep me rather busy in the years to come.

Harris is named after Martin Harris, a breeder who presented us with more than a dozen ravens during his lifetime – including most of our current birds – and who was a real character, and greatly loved by all of Team Raven.

Harris was in fact hatched on the very day of our old friend Martin’s funeral, which I attended down in Somerset with my deputy Ravenmaster, Shady Lane, both of us in full uniform. I can well remember driving down a few weeks later to collect the new little birdling, which was a bittersweet moment for us all, and we decided there and then to name the bird after Martin, as a reminder of the many people who love the ravens and who have been involved in their well-being.

I hope and trust that Harris has a long and happy life ahead of him.

* The longest-ever serving raven at the Tower was James Crow, who entered service around 1880 and didn’t pass away until 1924, making him an incredible forty-four years old. Ravens in the wild would be lucky to live into their teens or twenties. We would of course never name a raven James Crow these days – times, thank goodness, have changed.

5

Bird Life

Having met the ravens, you’ll probably be wanting to get a sense of their living arrangements.

It’s perhaps easiest to visualise where we all live at the Tower if you imagine a series of concentric circles. Right in the centre is the ancient White Tower; and then there’s the Inner Ward, which is enclosed by a massive wall with thirteen towers; and then there’s the narrow Outer Ward, protected by a second wall with six towers facing the river and two bastions on the north front. And then there’s the moat, which is now a dry moat. There’s no water in the moat. Most of us Yeoman Warders live right on the edge, facing the moat, but the ravens are slap-bang in the middle of things. They’re based in a purpose-built, state-of-the-art enclosure on the south side of Tower Green, in the Inner Ward. It is the perfect spot, sheltered but warm and sunny, at the centre of the life of the Tower but just tucked away enough to give them some privacy. It’s on the site of what was once the Grand Hall, which we think was probably where Anne Boleyn was imprisoned before her execution in 1536.

Living here at the Tower, for both the birds and the Yeoman Warders, is just like living anywhere else – apart from the fact that we have arrow slits for windows, our walls are forty feet high, and we’re locked in at night.

I suppose I’m used to this sort of thing. I lived in some pretty unusual places during my time in the army. I spent plenty of nights bivouacked in the jungle, and under the stars in the fields of South Armagh. I lived in Cyprus, among the orange trees and the olive groves, and up high in the mountains in the Balkans. When you’re a soldier you get used to roughing it – you’re at home everywhere and nowhere. The Tower is as peculiar and unexpected a place to live as anywhere.

There are about 140 residents here at the Tower. As well as the Yeoman Warders and their families, the Constable of the Tower lives here, the Resident Governor and Deputy Governor, the chaplain, the doctor, the Operations Manager, the Chief Warden, the head of Visitor Services, and the manager of the Fusilier Museum. We may share our home with millions of visitors every year, but we’re a little community just like any other. We even have our own club, the Yeoman Warders Club, the Keys, which must be one of the most exclusive clubs in the world since it’s only open to Tower residents, staff and invited guests.

Some people would find living in the Tower intolerable. You’re basically living in the middle of London, in a prime tourist destination, with the public continually passing through. It’s like a fishbowl. It’s certainly not for everyone. But for me, from the moment I arrived, it felt like coming home.

When I was young we lived in the shadow of Dover Castle. Dover sits facing France across the Channel, and is the traditional entry point for visitors from abroad. Home of the famous White Cliffs, Dover is what some people like to think of as the back door into England. I like to think of it as more of a grand entrance. Who knows how much I might have been influenced as a child, looking up at the old Norman castle, floodlit at night, the trains fuming into the station, the endless comings and goings of the ferries? Growing up in Dover I became accustomed to living in a place where people were continually passing through, tourists and travellers on their way in and out of England, and maybe I even had a dim sense of living in a place of great historic importance. I may have come a long way from Dover, but in some ways I haven’t come far at all.

As I have mentioned, most of us Yeoman Warders live in the walls on the outskirts of the Tower, in the Casemates, the outer battlements. The ravens live in the very shadow of the White Tower, a building that dominates the whole of the Tower of London even today, a symbol as much as it is a building, built centuries before the ‘starchitects’ and their skyscrapers that surround us now. Decades in construction, the White Tower was begun by William the Conqueror around the late 1070s, with the object of protecting London and impressing the populace, as well as controlling the approach to the City by river. Work on the White Tower was continued by William’s son William Rufus, and was eventually finished by Henry I around 1100, at which point Henry promptly imprisoned his chief minister, Ranulf Flambard, in the newly completed building, though Flambard soon escaped, climbing down a rope having plied his guards with drink. You can certainly try that with the Yeoman Warders today. It won’t work. But it’s certainly worth a try.

When I started as Ravenmaster the ravens were kept in rather cramped night boxes, constructed in the 1980s and built into the old inner walls of the Tower. There was nothing really wrong with the night boxes. They were definitely an improvement on how the ravens were housed before then. According to an article in Country Life magazine in December 1955, some of the Tower ravens were ‘locked in the basement of a house overlooking the Green and others were confined to a cage hung on the side of the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula’. Remnants of these rather primitive sleeping quarters remain today – and indeed are still in use by Merlina, who refuses to sleep with the other ravens, preferring her own company and a private night box behind an old lead-lined window on the ground floor of the Queen’s House on Tower Green, where she graciously allows the Constable of the Tower and his family to live.

The window of Merlina’s night box originally opened into the large basement of the Queen’s House, where coal was once stored, and which was first used to house ravens in 1946, when two ravens named Cora and Corax were put up there, perched on a pile of coal. We certainly don’t keep our ravens in coal bunkers any more. (One of the only times in recent history when the ravens have been kept inside at the Tower was during the avian flu virus in 2006, when tens of millions of birds worldwide died, and millions more were slaughtered to prevent the flu spreading. At that time we removed the ravens for their own safety to the upper Brick Tower, on the advice of the vets at London Zoo.)

The old night boxes just didn’t feel right to me. Ravens are wild birds who should be able to perch outside. They need to be able to fly back and forth. Like humans, they need freedom. But they also need protection. I strongly believe that if we’re going to continue to keep ravens at the Tower we have to make it as welcoming for them as possible, an environment that, if not entirely natural, is at least a place where they have room to roam in safety. So, soon after I had taken up the post of Ravenmaster, I discussed with the staff of Historic Royal Palaces – the independent charity that looks after the Tower of London, Hampton Court Palace, the Banqueting House, Kensington Palace, Kew Palace and Hillsborough Castle – the possibility of constructing some sort of large enclosure that would offer the birds protection at night but that we could leave open during the day, thus enabling them to continue to roam freely outside and socialise with one another but also to enjoy some privacy. (I don’t like the word cage, by the way. I don’t even like the word aviary. They’re words that imply capture and containment. I always refer to the ravens’ night-time quarters as the enclosure.) Historic Royal Palaces was as keen as I was to make improvements to the birds’ living arrangements.

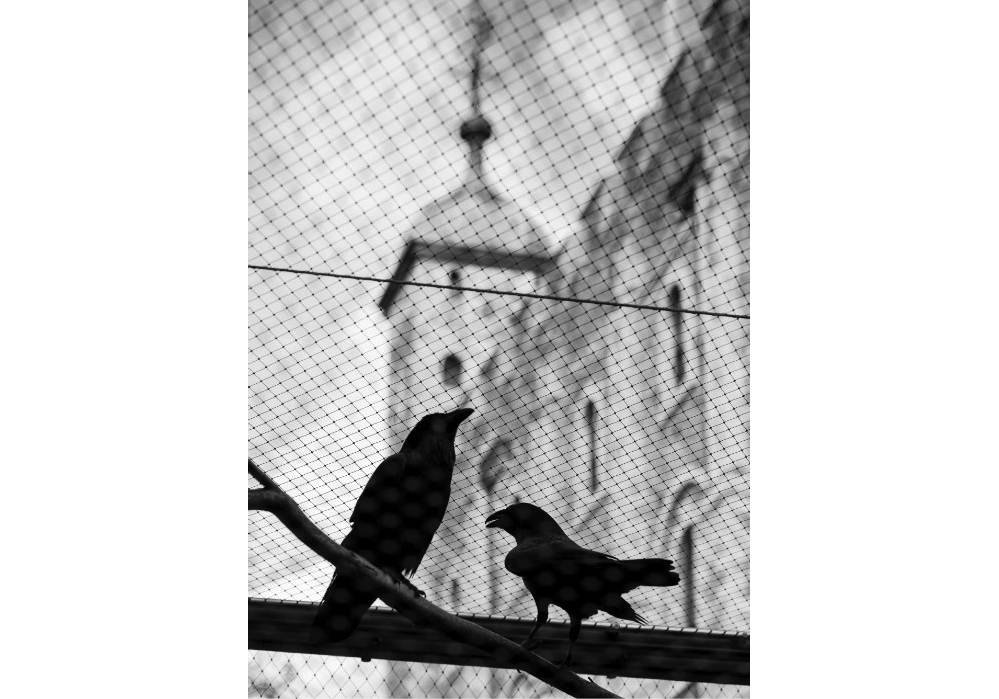

The raven enclosure at the Tower. (Courtesy of the author)

It took us about two years of research and consultation with London Zoo and Historic England and many other experts to get the design and development of the enclosure exactly right. Obtaining the planning permission alone was quite a feat. Just because we’re the Tower doesn’t mean we can make up our own rules. We had to obtain all the same planning permissions as anyone else. You can perhaps imagine the look on the face of the poor planning officer when our Planning Service Application arrived on their desk: ‘Erection of new cages and night boxes for Ravens, HM Tower of London.’ The important thing was to get the build right for the ravens, not just for the Tower or for my benefit or for the benefit of visitors; it needed to be something that the birds would want to use as a base.

The enclosure is made out of oak and a special fine wire which flexes if the birds should accidentally fly into it, to prevent them from getting injured. A tragic entry in the Tower Orders – the records of day-to-day activities at the Tower – for 18 April 1975 notes that Raven Brora was ‘Discovered entangled in wiring of the raven’s cage. Because of injuries had to be destroyed.’ It was of the utmost importance to me when designing the enclosure that this kind of terrible accident could never happen again.

One of the main requirements when we were planning the enclosure was that it had to be absolutely fox-proof. Even now, I’ll often arrive in the morning to signs that foxes have once again attempted to dig under the wire to get at the birds. They have no chance: I made sure that the wire goes straight down into the concrete and hardcore foundations. But you’d be amazed where foxes can get in. They can squeeze through the smallest gap – I’ve seen them manage to slip through gaps just a few inches wide, and once they’re in they’re in, and there’s absolutely nothing you can do about it. We’ve lost many a raven to foxes over the years. They sneak in under the drawbridges, crawl through the gutters, and trot down secret passageways. Sometimes I think my job title should be the Fox- and Ravenmaster: I’m engaged in a continual battle just trying to keep them apart.

The enclosure has separate areas inside for each bird or pair of birds to sleep in, and big sliding doors that allow me to open up the entire space so that they can come and go as they please. Each bird has its own perches and a large night box within the enclosure. All of this might sound straightforward, but it took a long time to work out the design, based on careful observation of the birds’ behaviour.

As I said, the enclosure is really only for night-time. The birds are out flying or walking around during the day, all day, every day. Very occasionally I keep them in the enclosure if they need looking after – if they’re sick, or if they just need a break. Being on show to the public every day can be exhausting, as we Yeoman Warders know only too well. Sometimes you just need to take a little time off to be by yourself and to relax and recharge. I’m always looking for signs of stress in the birds. If I sense that they need a break for whatever reason, I keep them in. I’ve been living and working with them for such a long time now that I can tell when something’s not right, the same as you can tell if your loved ones need some extra attention. You just know. The Tower is a community – and the ravens are an essential part of that community.

6

Tower Green

Now that you have a good sense of where we all live, you’ll probably want to know about our daily routine.

The Ravenmaster’s basic duties and responsibilities can be summarised thus:

1 Clean and prepare the ravens’ water bowls for the day.

2 Clean the ravens’ enclosures and remove any food they’ve discarded from the night before.

3 Check each raven closely for any health issues.

4 Feed the ravens, administer any medicines, such as worming tablets, monitor their food intake.

5 Release the ravens from the enclosures for the day.

6 Watch the ravens’ movements as they make their way to their territories, checking and recording any wing or leg damage.

7 Monitor the ravens throughout the day, ensuring the safety of both them and the public, and dealing with any issues arising.

8 Return the ravens safely to their enclosures at night.

9 Prepare food for the morning.

10 Final check before lights out.

In theory that’s it. Sounds pretty easy, doesn’t it? In practice, though, it’s a little bit more complicated.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s begin at the beginning. I’m up and out onto Tower Green at the crack of dawn. My first call of the day, every day, is to check on Merlina, since she mostly likes to stay out at night, up on the rooftops. Merlina is the only raven who does this. The other ravens all return to the enclosure on the south side of Tower Green. Merlina simply refuses to do so. She treats the rooftops around Tower Green as a penthouse suite – a place to retreat to and from which to contemplate the world. Once I can see her silhouette and I can hear her call, I make sure that the whole area around Tower Green is safe and clear from debris or anything that might harm the birds. Then I proceed to fill the water bowls.