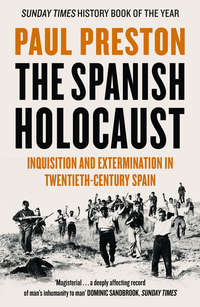

The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain

Queipo de Llano gave Díaz Criado unlimited powers and would hear no complaints against him. Díaz Criado himself refused to be bothered by details concerning the innocence or previous good deeds of his victims. On 12 August, the local press was issued a note prohibiting intercessions in favour of those arrested. It stated that ‘not only those who oppose our cause, but also those who support them or speak up for them will be regarded as enemies’.51 Díaz Criado was widely regarded as a degenerate who used his position to satisfy his bloodlust, to get rich and for sexual gratification. The head of Queipo’s propaganda apparatus, Antonio Bahamonde, whose disgust at what he witnessed eventually led to his defection, was appalled by Díaz Criado. He wrote:

Criado usually arrived around six in the evening. In an hour or less, he would go through the files, signing death sentences (about sixty per day) usually without hearing the accused. To anaesthetize his conscience or for whatever reason, he was always drunk. As dawn broke every day, he was to be seen, surrounded by his courtiers in the restaurant of the Pasaje del Duque, where he dined every night. He was an habitual client of the night clubs where he could be seen with admiring friends, flamenco singers and dancers, sad women trying to appear gay. He used to say that, once started, it was all the same to him to sign one hundred or three hundred death sentences and the important thing was to ‘cleanse Spain of Marxists’. I have heard him say: ‘Here, for decades to come, no one will dare move.’ He did not receive visits; only young women were allowed into his office. I know cases of women who saved their loved ones by submitting to his demands.52

Francisco Gonzálbez Ruiz, one-time Civil Governor of Murcia, had similar recollections of Díaz Criado: ‘in the small hours, after an orgy, still accompanied by prostitutes, and with unimaginable sadism, he would haphazardly apply his fateful mark “X2” to the files of those who were thus condemned to immediate execution’.53 One of Díaz Criado’s closest friends was a prostitute known as Doña Mariquita who had hidden him when he was on the run after his attempt to kill Azaña. Knowing this, many people paid her to intercede for their loved ones. Edmundo Barbero was present at gatherings in the early hours of the morning at which Díaz Criado, Sergeant Rebollo and Doña Mariquita would discuss the sexual and financial offers made on behalf of prisoners. On one such occasion, a bored Díaz Criado decided to take those present to a dawn execution. To his irritation, they arrived just as the echoes of the shots were dying away. However, he was mollified when the commander of the firing squad offered the women of the party his gun for them to finish off the dying. A sergeant of the Regulares then proceeded to remove gold teeth from the dead by bashing their heads with a stone.54

Bahamonde saw Díaz Criado drunk in a bar, signing death sentences. One of the few who survived to tell the tale later was the last Republican Civil Governor of Seville, José María Varela Rendueles. Díaz Criado began his interrogation with the words: ‘I have to say that I regret that you have not yet been shot. I would like to see your family in mourning.’ He said the same to Varela Rendueles’s mother some days later. Díaz Criado falsely accused Varela Rendueles of distributing arms to the workers. The only ‘proof’ that he could produce was a pistol once known to have been in Varela Rendueles’s possession found on a worker shot resisting the coup. The pistol had been stolen when Varela Rendueles’s office was looted. However, only after his successor as Civil Governor, Pedro Parias, had corroborated this did Díaz Criado grudgingly withdraw the accusation.55 Díaz Criado’s slipshod manner inevitably led to problems.

According to the usually reliable Bahamonde, ‘A friend of General Mola was shot, despite the fact that Mola himself had taken a great interest in his case, even telephoning Díaz Criado personally. Since he usually just signed the death sentences after barely flicking through the files, Díaz Criado failed to notice that on the day in question he had signed the death sentence of Mola’s friend.’56 Even so, Queipo tolerated Díaz Criado’s excesses; but, in mid-November 1936, Franco himself insisted on his removal. The immediate trigger had been that he had accused the Portuguese Vice-Consul in Seville, Alberto Magno Rodrigues, of espionage. Given the scale of Portuguese help to the rebel cause, and the efforts of Salazar’s government to secure international recognition for Franco, the accusation was acutely embarrassing. Moreover, it was absurd since Rodrigues was actually compiling information about German and Italian arms deliveries at the request of Franco’s brother, Nicolás. An enraged Queipo de Llano was forced to apologize to Rodrigues in front of Nicolás Franco. Now known as the ‘Caudillo’, Franco personally signed Díaz Criado’s posting to the Legion on the Madrid front, where he employed his brutal temperament against the soldiers under his command.57

Díaz Criado’s replacement by the Civil Guard Major Santiago Garrigós Bernabéu brought little relief to the terrorized population. Indeed, it was fatal for those who had been saved by the bribery of Doña Mariquita or by sexual submission to Díaz Criado himself. Francisco Gonzálbez Ruiz commented on the situation: ‘since some fortunate ones were saved by the opportune intervention of a female friend or by dint of paying a goodly sum, of course, when Díaz Criado was sacked, his successor felt the need to review the cases. Because the procedure followed had been corrupt, those who had been freed were now shot. Needless to say, nothing could help the thousands of innocents already dead.’58

One reason for which people were executed was having opposed the military coup of 10 August 1932. Among those murdered on these grounds were the then Mayor, José González Fernández de Labandera, the first Republican Mayor of Seville in April 1931 and Socialist deputy at the time, Hermenegildo Casas Jiménez, the then Civil Governor, Ramón González Sicilia, and the President of the Provincial Assembly, José Manuel Puelles de los Santos. After Puelles, a liberal and much loved doctor, had been arrested, his clinic was ransacked and he was murdered on 5 August. A similar fate awaited numerous other municipal and provincial officials.59

As soon as the ‘pacification’ of Cádiz and Seville was under way, Queipo de Llano could turn his attention to the neighbouring province of Huelva. Initially, because of the firm stance of the Civil Governor, Diego Jiménez Castellano, the Mayor, Salvador Moreno Márquez, and the local commanders of the Civil Guard, Lieutenant Colonel Julio Orts Flor, and of the Carabineros, Lieutenant Colonel Alfonso López Vicencio, the coup failed. Arms were distributed to working-class organizations but every effort was made to maintain order. Local rightists were detained for their safety and their weapons confiscated. Given the chaos and the hatred provoked by the uprising, it is a tribute to the success of the measures implemented by the Republican authorities that the number of right-wingers assassinated by uncontrolled elements in Huelva was limited to six.

Such was the confidence of the Madrid government that, on 19 July, the newly appointed Minister of the Interior, General Sebastián Pozas Perea, cabled the Civil Governor, Jiménez Castellano, and Lieutenant Colonel Orts Flor: ‘I recommend that you mobilize the miners to use explosives to annihilate these terrorist gangs. You can be confident that the military column advancing triumphantly on Córdoba and Seville will shortly wipe out the last few seditious traitors who, in their last throes, have unleashed the most cruel and disgusting vandalism.’ In response to this wildly over-optimistic telegram, the text of which would later be falsified by the rebels, it was decided to send a column from the city to attack Queipo de Llano in Seville. The column consisted of sixty Civil Guards, sixty Carabineros and Assault Guards plus about 350 left-wing volunteers from various towns, including Socialist miners. It was accompanied by two of Huelva’s parliamentary deputies, the Socialists Juan Gutiérrez Prieto and Luis Cordero Bel.

In fact, the police, the Civil Guard and the army in Huelva were heavily infiltrated by conspirators. One of the most untrustworthy, Major Gregorio Haro Lumbreras of the Civil Guard, was placed in command of the force being sent to attack Queipo. Haro had been involved in the Sanjurjada and was in close touch with José Cuesta Monereo, who had planned the military coup in Seville. To prevent his real plans being frustrated by the workers in the column, Haro Lumbreras and his men had left for Seville several hours before the civilian volunteers. Along the sixty-two miles separating the two cities, his force was swelled by Civil Guards from other posts. On reaching Seville, Haro Lumbreras liaised with Queipo and Cuesta Monereo then retraced his steps to set up an ambush of the militias coming from Huelva. On 19 July, at a crossroads known as La Pañoleta, his men opened fire on the miners with machine-guns. Twenty-five were killed and seventy-one were taken prisoner, of whom three soon died of their wounds. The remainder, including the Socialist deputies, escaped. Haro’s men suffered no casualties apart from one man who broke his leg getting out of a truck. The prisoners were taken to the hold of the prison ship Cabo Carvoeiro anchored in the River Guadalquivir. At the end of August, they would be ‘tried’ and found guilty of the surrealistic crime of military rebellion against ‘the only legitimately constituted power in Spain’. The sixty-eight prisoners were then divided into six groups, taken to six areas of Seville where working-class resistance had been significant, and shot. Their bodies were left in the streets for several hours to terrorize further a population which had already seen more than seven hundred people executed since Queipo de Llano’s triumph.60

Huelva itself would not fall for another ten days. In the meantime, the conquest of the territory between Huelva and Seville was carried out by columns organized by the military and financed by wealthy volunteers with access to cars and weaponry. After taking part in the suppression of the working-class areas of Seville, a Carlist column organized by a retired Major Luis Redondo García attacked small towns to the south-east of Seville.61 Another typical column was put together by the wealthy landowner Ramón de Carranza. He had been involved in the preparations for the coup and, with a group of friends, some from the Aero Club and the landowners’ casino, had taken part in the repression of the working-class districts of Triana and La Macarena. Queipo rewarded him by making him Mayor of Seville. Carranza was the son of the cacique of Cádiz, Admiral Ramón de Carranza, the Marqués de Villapesadilla, who owned 5,600 acres in estates near Algeciras and in Chiclana.62 From 23 July until late August, Carranza alternated his administrative duties with the leadership of a column that occupied the towns and villages in the Aljarafe region to the west of Seville.

It was no coincidence that in many of these municipalities extensive properties were owned by Carranza and other wealthy members of the column such as his friend Rafael de Medina. Their itineraries were often dictated by the location of their estates. In most villages, a Popular Front committee had been set up, with representation of all Republican and left-wing groups, usually under the chairmanship of the mayor. They arrested known sympathizers of the military rebels and confiscated their weapons. This was an area of big estates, producing wheat and olives, with large areas of cork oaks around which cattle, sheep, goats and pigs grazed. The committees centralized food supplies and, in some cases, collectivized estates. The owners had a burning interest in the recovery of the farms that now fed their left-wing enemies.

Carranza’s column moved into the Aljarafe, attacking towns and villages such as Saltares, Camas, Valencina, Bollullos and Aznalcázar. Armed with mortars and machine-guns, they met little resistance from labourers armed only with hunting shotguns or farm implements. At one of the first villages reached, Castilleja, Medina liberated estates belonging to his friend the Marqués de las Torres de la Presa. In Aznalcázar, the Socialist Mayor, who, according to Medina’s own account, handed over the pueblo with great dignity and grace, was taken to Seville and shot. Moving on to Pilas and Villamanrique, the column recaptured estates owned by Medina himself and his father. Eventually, on 25 July, they went as far as Almonte in Huelva. As each village fell, Carranza would arrest the municipal authorities, establish new town councils, shut down trade union offices and take truckloads of prisoners back to Seville for execution.63

On 27 July, Carranza’s column reached one such town, Rociana in Huelva, where the left had taken over in response to news of the military coup. There had been no casualties but a ritual destruction of the symbols of right-wing power, the premises of the landowners’ association and two clubs, one used by the local Falange. Twenty-five sheep belonging to a wealthy local landowner were stolen. The parish church and rectory had been set alight, but the parish priest, the sixty-year-old Eduardo Martínez Laorden, his niece and her daughter who lived with him had been saved by local Socialists and given refuge in the house of the Mayor. On 28 July, Father Martínez Laorden made a speech from the balcony of the town hall: ‘You all no doubt believe that, because I am a priest, I have come with words of forgiveness and repentance. Not at all! War against all of them until the last trace has been eliminated.’ A large number of men and women were arrested. The women had their heads shaved and one, known as La Maestra Herrera, was dragged around the town by a donkey, before being murdered. Over the next three months, sixty were shot. In January 1937, Father Martínez Laorden made an official complaint that the repression had been too lenient.64

When Gonzalo de Aguilera shot six labourers in Salamanca, he perceived himself to be taking retaliatory measures in advance. Many landowners did the same by joining or financing mixed columns like that of Carranza. They also played an active role in selecting victims to be executed in captured villages. In a report to Lisbon, in early August, the Portuguese Consul in Seville praised these columns. Like the Italian Consul, he had been given gory accounts of unspeakable outrages allegedly committed against women and children by armed leftist desperadoes. Accordingly, he reported with satisfaction that, ‘in punishing these monstrosities, a harsh summary military justice is applied. In these towns, not a single one of the Communist rebels is left alive, because they are all shot in the town square.’65 In fact, these shootings reflected no justice, military or otherwise, but rather the determination of the landowners to put the clock back. Thus, when labourers were shot, they were made to dig their own graves first, and Falangist señoritos shouted at them, ‘Didn’t you ask for land? Now you’re going to have some, and for ever!’66

The atrocities carried out by the various columns were regarded with relish by Queipo de Llano. In a broadcast on 23 July, he declared, ‘We are determined to apply the law without flinching. Morón, Utrera, Puente Genil, Castro del Río, start digging graves. I authorize you to kill like a dog anyone who dares oppose you and I say that, if you act in this way, you will be free of all blame.’ In part of the speech that the censorship felt was too explicit to be printed, Queipo de Llano said, ‘Our brave Legionarios and Regulares have shown the red cowards what it means to be a man. And incidentally the wives of the reds too. These Communist and anarchist women, after all, have made themselves fair game by their doctrine of free love. And now they have at least made the acquaintance of real men, not wimpish militiamen. Kicking their legs about and squealing won’t save them.’67

Queipo de Llano’s speeches were larded with sexual references. On 26 July, he declared: ‘Sevillanos! I don’t have to urge you on because I know your bravery. I tell you to kill like a dog any queer or pervert who criticizes this glorious national movement.’68 Arthur Koestler interviewed Queipo de Llano at the beginning of September 1936: ‘For some ten minutes he described in a steady flood of words, which now and then became extremely racy, how the Marxists slit open the stomachs of pregnant women and speared the foetuses; how they had tied two eight-year-old girls on to their father’s knees, violated them, poured petrol on them and set them on fire. This went on and on, unceasingly, one story following another – a perfect clinical demonstration in sexual psychopathology.’ Koestler commented on the broadcasts: ‘General Queipo de Llano describes scenes of rape with a coarse relish that is an indirect incitement to a repetition of such scenes.’69 Queipo’s comments can be contrasted with an incident in Castilleja del Campo when a truckload of prisoners was brought for execution from the mining town of Aznalcóllar, which had been occupied on 17 August by Carranza’s column. Among them were two women tied together, a mother and her daughter who was in the final stages of pregnancy and gave birth as she was shot. The executioners killed the baby with their rifle butts.70

The most important of the columns carrying out Queipo’s bidding was commanded by the stocky Major Antonio Castejón Espinosa. After taking part in the repression of Triana and La Macarena in Seville itself, and prior to setting out on the march to Madrid, Castejón made a number of rapid daily sorties to both the east and west of the city. In its war on the landless peasantry, Castejón’s column drew on the training and experience of the Legion and the Civil Guard and had the added advantage of the artillery directed by Alarcón de la Lastra. Fulfilling Queipo’s threats, to the east the column conquered Alcalá de Guadaira, Arahal, La Puebla de Cazalla, Morón de la Frontera, reaching Écija before moving south to Osuna, Estepa and La Roda, advancing as far as Puente Genil in Córdoba, seventy-five miles from Seville. To the west, at Valencina del Alcor, just outside Seville, Castejón’s forces liberated the estate of a rich retired bullfighter, Emilio Torres Reina, known as ‘Bombita’. ‘Bombita’ himself enthusiastically joined in the fighting and the subsequent ‘punishment’ of the prisoners. Castejón went as far as La Palma del Condado in Huelva, thirty-four miles from Seville. First the town was bombed, which provoked the murder of fifteen right-wing prisoners by enraged anarchists. On 26 July, La Palma was captured in a pincer action by the columns of both Castejón and Carranza, who bitterly disputed the credit of being first.71

When forces of the Legion sent by Queipo de Llano finally took Huelva itself on 29 July, they discovered that the Mayor and many of the Republican authorities had managed to flee on a steamer to Casablanca. The city fell after brief resistance in the Socialist headquarters (the Casa del Pueblo). Seventeen citizens were killed in the fighting and nearly four hundred prisoners were taken. Executions began immediately. Corpses were regularly found in the gutters. Still basking in the glory of the massacre of the miners at La Pañoleta, Major Haro Lumbreras was named both Civil and Military Governor of Huelva. Those Republican civil and military authorities who had not managed to escape – the Civil Governor and the commanders of the Civil Guard and the Carabineros – were put on trial on 2 August, charged with military rebellion. Haro testified against his immediate superior, Lieutenant Colonel Orts Flor, who had organized the miners’ column sent to Seville.

To inflate his own heroism, and inadvertently revealing his own obsessions, Haro claimed that the orders from General Pozas passed on by Orts which had instigated the expedition were to ‘blow up Seville and fuck the wives of the fascists’. Unsurprisingly, the accused were found guilty and sentenced to death. Numerous conservatives and clerics whose lives had been saved by the Civil Governor, Diego Jiménez Castellano, sent telegrams to Seville on 4 August desperately pleading for clemency. Queipo de Llano replied: ‘I regret that I cannot respond to your petition for pardon for the criminals condemned to death, because the critical situation through which Spain is passing means that justice cannot be obstructed, for the guilty must be punished and an example made of them.’ Diego Jiménez Castellano, Julio Orts Flor and Alfonso López Vicencio were shot shortly after 6.00 p.m. on 4 August.72

With Huelva itself in rebel hands, the process began, as it had in Cádiz and Seville, of columns being sent out to mop up the remainder of the province. Carranza’s column was involved in the taking of nearby towns to the south like Lepe, Isla Cristina and Ayamonte. Many of the Republicans who were arrested and taken to Huelva for trial were murdered along the way.73 In the north, the rebels already had a bridgehead in the town of Encinasola, where the rising had triumphed immediately. The right could count on support from Barrancos across the Portuguese frontier.74 With considerable bloodshed, a major role in the capture of towns and villages to the east and north of the capital was played by Luis Redondo’s column of Carlists from Seville. The mining towns of the north were centres of obdurate resistance, holding out for some weeks despite artillery bombardment. Higuera de la Sierra fell on 15 August. Zalamea la Real on the edge of the Riotinto mining district fell the next day. The capture of these villages was followed by indiscriminate shootings.75

The savagery increased as the columns entered Riotinto. The inhabitants had fled from the village of El Campillo. Finding it deserted, Redondo gave the order to burn it to the ground. Queipo de Llano broadcast the absurd lie that the local anarchists had burned twenty-two rightists alive and then set fire to their own homes. An air raid on Nerva on 20 August killed seven women, four men, a ten-year-old boy and six-month-old girl. One right-winger had been killed before the arrival of Redondo. The Communist Mayor ensured that twenty-five others who were in protective custody were unharmed, despite the popular outrage after the bombing raid. When the village was taken, Redondo’s men executed 288 people. In Aroche, ten right-wingers were killed and, when Redondo’s column arrived on 28 August, despite the fact that many leftists had fled north towards Badajoz, his men executed 133 men and ten women. The town’s female population was subjected to humiliation and sexual extortion. Reports of this terror ensured that resistance elsewhere would be dogged. The siege of El Cerro de Andévalo lasted over three weeks and required the contribution of three columns of Civil Guards, Falangists and Requetés. There the local CNT committee or Junta had protected the nuns in a local convent but were unable to prevent attacks on church property. The repression when the town fell on 22 September was ferocious. In nearby Silos de Calañas, women and children were shot along with the men. Large numbers of refugees now headed north towards the small area in Badajoz still not conquered by the rebels.76

Meanwhile, in Moguer to the south of the province, and in Palos de la Frontera to the east of the provincial capital, members of the clergy and local rightists had been taken into protective custody. In Moguer, as news filtered through of the repression in Seville, on 22 July the parish church was set on fire and a retired lieutenant colonel of the army was murdered after his house was attacked and looted by a large mob. The Mayor, Antonio Batista, managed to prevent any further deaths. In Palos, the Socialist Mayor, Eduardo Molina Martos, and the PSOE deputy Juan Gutiérrez Prieto tried unsuccessfully to stop the local CNT burning down church buildings including the historic monastery of La Rábida but did prevent any executions. On 28 July, Palos was captured by the Civil Guard without opposition and, on 6 August, Falangists from Huelva began a series of extra-judicial executions.

Gutiérrez Prieto, a talented and highly popular lawyer, was captured in Huelva on 29 July and tried on 10 August. In addition to military rebellion, he was accused of responsibility for virtually every action of the left in the province and sentenced to death. Numerous conservatives and ecclesiastical dignitaries interceded on his behalf. To counteract these pleas, Haro Lumbreras made a statement to the press which echoed the sexual obsessions of his distortion of General Pozas’s orders. No right-wingers had been harmed in Palos, yet he stated: