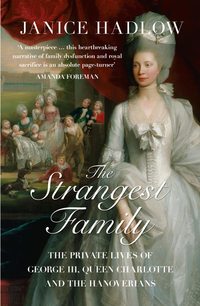

The Strangest Family: The Private Lives of George III, Queen Charlotte and the Hanoverians

Although George confessed he was sometimes ‘extremely hurt, at the many truths’ Bute told him, he did not doubt that Bute’s ‘constant endeavours to point out these things in me that are likely to destroy any attempts at raising my character’ were for his own good, ‘a painful, though necessary office’.101 They were also, in George’s eyes, a sign of the depth of Bute’s regard for him, since only someone who really loved him would be prepared to criticise him so readily. ‘Flatterers, courtiers or ministers are easily got,’ his father had explained to him in his ‘Instructions’, ‘but a true friend is hard to be found. The only rule I can give you to try them by, is that they will tell you the truth.’ If George discovered such an honest man, he should do all he could to keep him, even if that required him to bear ‘some moments of disagreeable contradictions to your passions’.102

George had no difficulty in submitting to Bute’s comprehensive programme of self-improvement, sadly convinced that all the criticisms were deserved. His opinion of himself could not have been lower. He was, he confessed, ‘not partial to myself’, regularly describing both his actions and himself as despicable. ‘I act wrong perhaps in most things,’ he observed, adding that he might be best advised to ‘retire, to some distant region where in solitude I might for the rest of my life think on the faults I have committed, that I might repent of them’.103 He was afraid that he was ‘of such an unhappy nature, that if I cannot in good measure alter that, let me be ever so learned in what is necessary for a king to know, I shall make but a very poor and despicable figure’.104 When he contemplated his many shortcomings and failures, he was amazed that Bute was prepared to remain with him at all.

The idea that Bute might leave – that his patience with his underachieving charge might exhaust itself – threw the prince into paroxysms of anxiety. Bute seems often to have deployed the idea of potential abandonment as a means of reminding George of the totality of his dependency. The merest suggestion of it was enough, George admitted, to ‘put me on the rack’, declaring that the prospect was ‘too much for mortal man to bear’.105 His self-esteem was so low that George was sure that if Bute were to depart, he would have only himself to blame. ‘If you should resolve to set me adrift, I could not upbraid you,’ he wrote resignedly, ‘as it is the natural consequence of my faults, and not want of friendship in you.’106 George was endlessly solicitous about Bute’s health: the possibility of losing him through illness or even death was a horrifying prospect that loomed large in George’s nervous imagination; his letters are full of enquiries and imprecations about the earl’s wellbeing. When Bute and his entire family fell seriously ill with ‘a malignant sore throat’, the prince was beside himself with worry. He took refuge in his conviction that ‘you, from your upright conduct, have some right to hope for particular assistance from the great Author of us all’.107 It was inconceivable that God would not value Bute’s virtues as highly as George did; when the earl recovered, George presented his doctors with specially struck gold medals of himself to mark his appreciation of their care.

From the mid-1750s to the time of his accession, the entire object of George’s existence was to reshape and remodel himself into the type of man who could fulfil the role of king, as Bute had so alluringly redefined it; but this internal reformation was not accompanied by a change in his way of life. He remained closeted at home with his mother and the earl, and for all Bute’s desire to reform the prince’s personality, he left many of George’s deepest beliefs untouched – partly because he shared some of them himself. One of the reasons George found Bute so congenial was because he endorsed so much of the vision of the world that the prince had inherited from his mother. For all his confidence in the righteousness of his prescriptions, and for all the energy and enthusiasm with which he argued them, there was in Bute himself a core of austerity and reserve. He was not a naturally sociable man, preferring to judge society – often rather severely – than to engage with it. He had a natural sympathy with the suspicion and apprehension with which Augusta encountered anything beyond the narrow bounds of her immediate family. He offered George no alternative perspective, but instead confirmed the prince’s pessimism about the moral worth and motives of others, a bleak scepticism that was to endure throughout his life. ‘This,’ wrote George, ‘is I believe, the wickedest age that ever was seen; an honest man must wish himself out of it; I begin to be sick of things I daily see; for ingratitude, avarice and ambition are the principles men act by.’108

Bute’s counsels did nothing to dilute the mix of fear and contempt with which the prince contemplated the world he must one day join. ‘I look upon the majority of politicians as intent on their own private interests rather than of the public,’ George wrote with grim certainty.109 William Pitt, his grandfather’s minister, was ‘the blackest of hearts’. His uncle, Cumberland, was still, George believed, capable of mounting a coup d’état to prevent his accession: ‘in the hands of these myrmidons of the blackest kind, I imagine any invader with a handful of men might put himself on the throne and establish despotism here’.110 He had fully absorbed Augusta’s deep-seated hostility to his grandfather and, like her, could not find a good word to say about ‘this Old Man’. George II’s behaviour was ‘shuffling’ and ‘unworthy of a British monarch; the conduct of this old king makes me ashamed of being his grandson’.111 There was only one man deserving of George’s confidence, and that was Bute. ‘As for honesty,’ he told Bute, ‘I have already lived long enough to know you are the only man I shall ever meet who possesses that quality and who at all times prefers my interest to their own; if I were to utter all the sentiments of my heart on that subject, you would be troubled with quires of paper.’112

By 1759, Bute’s ascendancy over the prince seemed complete. The prospect of translating their political ideas into practice once George II was dead offered a beacon of hope which sustained them through adversity – it had been agreed at the very outset of their relationship that Bute was to become First Lord of the Treasury when George was king. But in that year, the earl’s authority was challenged from a direction that neither he and nor perhaps George himself had anticipated.

*

In the winter, conducting one of his regular inventories of George’s state of mind, Bute became convinced the prince was hiding something from him. Pressed to declare himself, George was cautious at first, but eventually began a hesitant explanation of his mood. At first, he confined himself to generalities. ‘You have often accused me of growing grave and thoughtful,’ he confessed. ‘It is entirely owing to a daily increasing admiration of the fair sex, which I am attempting with all the philosophy and resolution I am capable of, to keep under. I should be ashamed,’ he wrote ruefully, ‘after having so long resisted the charms of those divine creatures, now to become their prey.’113 There was no doubt that the twenty-one-year-old George was still a virgin. His younger brother Edward, far more like his father and grandfather in his tastes, had eagerly embarked on affairs as soon as he had escaped the schoolroom, but George had thus far remained true to his mother’s principles of self-denial and restraint. Walpole believed that if she could, Augusta would have preferred to keep her son perpetually away from the lures of designing women: ‘Could she have chained up his body as she did his mind, it is probable that she would have preferred him to remain single.’ But the worldly diarist thought he knew the Hanoverian temperament well enough to be convinced this was an impossible objective. ‘Though his chastity had hitherto remained to all appearances inviolate, notwithstanding his age and sanguine complexion, it was not to be expected such a fast could be longer observed.’114 Certainly this was how the prince himself felt, confessing to Bute that he found repressing his desires harder and harder. ‘You will plainly feel how strong a struggle there is between the boiling youth of 21 years and prudence.’ He hoped ‘the last will ever keep the upper hand, indeed if I can but weather it, marriage will put a stop to this conflict in my breast’.115

As Bute suspected, George’s disquiet reflected something more than a general sense of frustration. Incapable of concealing anything of importance from Bute, he wrote another letter which confessed all. ‘What I now lay before you, I never intend to communicate to anyone; the truth is, the Duke of Richmond’s sister arrived from Ireland towards the middle of November. I was struck with her first appearance at St James’s, and my passion has increased every time I have since beheld her; her voice is sweet, she seems sensible … in short, she is everything I can form to myself lovely.’ Since then, his life had hardly been his own: ‘I am grown daily unhappy, sleep has left me, which was never before interrupted by any reverse of fortune.’ He could not bear to see other men speak to her. ‘The other day, I heard it suggested that the Duke of Marlborough made up to her. I shifted my grief till I retired to my chamber where I remained for several hours in the depth of despair.’ His love and his intentions were, he insisted, entirely honourable: ‘I protest before God, I never have had any improper thoughts with regard to her; I don’t deny having flattered myself with hopes that one day or another you would consent to my raising her to a throne. Thus I mince nothing to you.’116

Lady Sarah Lennox, daughter of the Duke of Richmond (which title her brother inherited), was almost as well connected as George himself. Her grandfather was a son of Charles II and his mistress Louise de Kérouaille. She had four sisters, three of whom had done very well in the marriage market. The eldest, Caroline, was wife to the politician Henry Fox, and mother to Charles. Emily had married the Earl of Kildare, and Louisa had made an alliance with an Irish landowner, Thomas Connolly. From her youth, Sarah was one of the liveliest members of a famously lively family. As a very small child, she had caught the eye of George II. He had invited her to the palace where she would watch the king at his favourite pastime, ‘counting his money which he used to receive regularly every morning’. Once, with heavy-handed playfulness, he had ‘snatched her up in his arms, and after depositing her in a large china jar, shut down the lid to prove her courage’.117 When her response was to sing loudly rather than to cry, he was delighted.

When her mother died, Sarah went to live with her sister, Lady Kildare, in Ireland. She did not return to court until she was fourteen. George II, who had not forgotten her, was pleased to see her back, but ‘began to joke and play with her as if she were still a child of five. She naturally coloured up and shrank from this unaccustomed familiarity, became abashed and silent.’ The king was disappointed and declared: ‘Pooh! She’s grown quite stupid!’118

Those who found themselves on the receiving end of his grandfather’s insensitivity aroused the sympathy of the Prince of Wales. ‘It was at that moment the young prince … was struck with admiration and pity; feelings that ripened into an attachment which never left him until the day of his death.’119 That was the account Sarah gave to her son in 1837, and which he transcribed with reverential filial piety. In letters she wrote to her sisters at the time, Sarah was not so sentimental. After her first meeting with George, she described her clothes – blue and black feathers, black silk gown and cream lace ruffles – with far more detail than her encounter with the prince. She hardly spoke to him at all. Too shy to approach her directly, the prince had instead approached her older sister Caroline, stumbling out unaccustomed praises of her beauty and charm.

George was not the only man to find Sarah Lennox mesmerisingly attractive. It was hard to pin down the exact nature of her appeal, which was not always apparent at first sight. Her sisters failed to understand it at all. ‘To my taste,’ wrote Emily, ‘Sarah is merely a pretty, lively looking girl and that is all. She has not one good feature … her face is so little and squeezed, which never turns out pretty.’120 Her brother-in-law Henry Fox thought otherwise. ‘Her beauty is not easily described,’ he wrote, ‘otherwise than by saying that she had the finest complexion, the most beautiful hair, and prettiest person that was ever seen, with a sprightly and fine air, a pretty mouth, remarkably fine teeth, and an excess of bloom in her cheeks, little eyes – but that is not describing her, for her great beauty was a peculiarity of countenance that made her at the same time different from and prettier than any other girl I ever saw.’121 Horace Walpole saw her once as she acted in amateur theatricals at Holland House; his detached connoisseur’s eye caught something of her intense erotic promise: ‘When Lady Sarah was all in white, with her hair about her ears and on the ground, no Magdalen by Caravaggio was half so lovely and expressive.’122 Sarah, unfazed by the comparison to a fallen woman, declared its author ‘charming’. She liked Walpole, she said with disarming honesty, because he liked her.

This cheerful willingness to find good in all those who found good in her no doubt smoothed her encounters with the awkward Prince of Wales. They met at formal Drawing Rooms and private balls, and George’s attention was so marked that it was soon noticed by the sharp-eyed Henry Fox. At this point, he did not take it seriously; it was no more than an opportunity for a good tease. ‘Mr Fox says [George] is in love with me, and diverts himself extremely,’ Sarah told Emily wryly.123

Bute, however, knew that George’s feelings were anything but a joke. Having declared them to his mentor, George was now desperate to know whether Sarah Lennox could be considered a suitable candidate for marriage. It seems never to have occurred to him that this was a decision he might make for himself. He submitted himself absolutely to Bute’s judgement, assuring him that no matter what the earl concluded, he would abide by his decision. He hoped for a favourable answer, but insisted that their relationship would not be affected if it were not so: ‘If I must either lose my friend or my love, I shall give up the latter, for I esteem your friendship above all earthly joy.’124 The rational part of him must have known what Bute’s answer would be. It was inconceivable that he should marry anyone but a Protestant foreign princess; an alliance between the royal house and an English aristocratic family would overthrow the complex balance of political power on which the mechanics of the constitutional settlement depended.

To marry into a family that included Henry Fox was, if possible, even more outrageously improbable. Henry was the brother of Stephen Fox, the lover of Lord Hervey, the laconic Ste, who had been driven into a jealous fury by the ambiguous relationship between Hervey and Prince Frederick. Henry Fox was one of the most controversial politicians of his day: able, amoral and considered spectacularly corrupt, even by the relaxed standards of eighteenth-century governmental probity. A man described by the Corporation of the City of London as a ‘public defaulter of unaccounted millions’ was unlikely to prove a suitable brother-in-law to the heir to the throne. Bute’s judgement was therefore as unsurprising as it was uncompromising: ‘God knows, my dear sir, I with the utmost grief tell it you, the case admits of not the smallest doubt.’ He urged George to consider ‘who you are, what is your birthright, what you wish to be’. If he examined his heart, he would understand why the thing he hoped for could never happen. The prince declared himself reluctantly persuaded that Bute was right. ‘I have now more obligations to him than ever; he has thoroughly convinced me of the impossibility of ever marrying a countrywoman.’ He had been recalled to a proper sense of duty. ‘The interest of my country shall ever be my first care, my own inclinations shall ever submit to it; I am born for the happiness or misery of a great nation, and consequently must often act contrary to my passions.’125

George’s renunciation was made easier by the fact that he did not see the object of his passion for some months. The next time he did so, he was no longer Prince of Wales but king. George II died in October 1760; Sarah Lennox went to court in 1761, when all the talk was of the impending coronation. As soon as he saw her again, all George’s hard-won resolution ebbed away, as ‘the boiling youth’ in him made him forget all the promises he had made to Bute. Despite his undertaking to give her up, he took the unprecedented step of declaring to her best friend the unchanged nature of his feelings for Sarah. One night at court, he cornered Lady Susan Fox-Strangways, another member of the extensive Fox clan. The conversation that followed was so extraordinary that Lady Susan repeated it to Henry Fox, who transcribed it. The king asked Lady Susan if she would not like to see a coronation. She replied that she would.

K: Won’t it be a finer sight when there is a queen?

LS: To be sure, sir.

K: I have had a great many applications from abroad, but I don’t like them. I have had none at home. I should like that better.

LS: (Nothing, frightened)

K: What do you think of your friend? You know who I mean; don’t you think her fittest?

LS: Think, sir?

K: I think none so fit.

Fox then said that George ‘went across the room to Lady Sarah, and bid her ask her friend what he had been saying and make her tell her all’.126

The fifteen-year-old Sarah, never very impressed by George’s attentions, had been conducting a freelance flirtation of her own, which had just come to an end, and she was in no mood to be polite to other suitors, even royal ones. When George approached her at court soon after, she rebuffed all his attempts to discuss the conversation he had had with Lady Susan. When he asked whether she had spoken to her friend, she replied monosyllabically that she had. Did she approve of what she had heard? Fox reported that ‘She made no answer, but looked as cross as she could. HM affronted, left her, seemed confused, and left the Drawing Room.’127

Fox worked away, trying to discover the true state of George’s feelings for Lady Sarah. Despite the unfortunate snub, they seemed to Fox as strong as ever. He was less certain, however, of where they might lead. Fox told his wife that he was not sure whether George really intended to marry her, adding that ‘whether Lady Sarah shall be told of what I am sure of, I leave to the reader’s discretion’.128 If a crown was out of the question, it might be worth Sarah settling for the role of royal mistress. At the Birthday Ball a few months later, Fox’s hopes of the ultimate prize revived once more. ‘He had no eyes but for her, and hardly talked to anyone else … all eyes were fixed on them, and the next morning all tongues observing on the particularity of his behaviour.’129 But after over a year of encouraging signals, there was still no sign of any meaningful declaration from the king. Determined to bring matters to a head, Lady Sarah was sent back to court with very precise instructions to do all she could to extract from her vague suitor some concrete sense of his intentions. As she explained to Lady Susan, Fox had coached her to perfection: ‘I must pluck up my spirits, and if I am asked if I have thought of … or if I approve of … I am to look him in the face and with an earnest but good-humoured countenance, say “that I don’t know what I ought to think”. If the meaning is explained, I must say “that I can hardly believe it” and so forth.’ It was all very demanding. ‘In short, I must show I wish it to be explained, without seeming to suggest any other meaning; what a task it is. God send that I may be enabled to go through with it. I am allowed to mutter a little, provided that the words astonished, surprised, understand and meaning are heard.’130

Yet for all Lady Sarah’s careful preparation, she could not get near the king, and nothing came of it. Then, at the end of June 1761, the king made yet another of his cryptically encouraging remarks, this time to Sarah’s sister Emily, telling her: ‘For God’s sake, remember what I said to Lady Susan … and believe that I have the strongest attachment.’ A few days later, Fox was dumbstruck to be told that the meeting of the Privy Council summoned for 8 July was ‘to declare His Majesty’s intention to marry a Princess of Mecklenburg!’131

No one could believe it, least of all Sarah. On the day after the meeting – and its purpose – had been announced, ‘the hypocrite had the face to come up and speak to me with all the good humour in the world, and seemed to want to speak to me but was afraid. There is something so astonishing in all this that I can hardly believe …’132 For months, Lady Sarah and Fox puzzled and obsessed over what the strange and confusing episode had meant. Lady Sarah could not help but feel humiliated, but was determined not to let others see it. ‘Luckily for me, I did not love him, and only liked him, nor did the title weigh anything with me; or so little at least, that my disappointment did not affect my spirits above one hour or two, I believe.’133 If that was an exaggeration born of bravado, it was nonetheless true that she had recovered her spirits sufficiently to accept without a qualm the invitation to act as one of the bridesmaids at George’s wedding a few months later. ‘Well, Sal,’ sighed Fox, making his own final comment on the whole affair, ‘you are the first virgin’ – or as he jokingly pronounced it, ‘the first vargin’ – ‘in England, and you shall take your place in spite of them all, and the king shall behold your pretty face and weep.’134

Had either Fox or Lady Sarah asked George to explain his behaviour, it is hard to know what he might have said. No one could deny that his conduct had not been strictly honourable. Although he had not made a direct proposal of marriage, he had come pretty close to it, and he had certainly encouraged Sarah to think of him as some kind of suitor when he was not, as he knew only too well, in a position to offer any respectable outcome to their developing relationship. By January 1761, preliminary enquiries had begun in Germany to find him a woman he could marry, but, despite all his assurances to Bute and to himself, he was still irresistibly drawn to Sarah Lennox, dropping suggestions and making promises that he knew he could not keep. When, in the spring, he made his fateful declaration to Lady Susan Fox-Strangways, he was privately reading reports evaluating the looks and characters of every German Protestant princess of marriageable age. His formal proposal to the Princess of Mecklenburg was accepted on 17 June, only days before he made yet another of his insistent speeches to Sarah’s sister Emily, beseeching her to ‘believe that I have the strongest attachment’.

George’s motives, in the end, remain opaque; but perhaps he explained his actions to himself by considering them as the contradictory product of the two conflicting aspects of his identity. The king in him submitted, as he knew he must, to an arranged marriage with a woman he had never seen; but the ‘boiling youth of 21 years’ found it harder to accept that he ‘must often act contrary to my passions’, and that to ‘the interest of my country … my own inclinations shall ever submit’. In 1760–61, for the first and only time in his life, George allowed his heart to rule his head and followed the call of instinct, not obligation. He knew from the beginning which way it would end, recognising that he was formed for duty not rebellion. However, before the world of you shall closed inevitably and finally over the prospect of you could, he enjoyed a brief flirtation with the alternative. While he kept his sanity, he would never stray again.

CHAPTER 4

The Right Wife