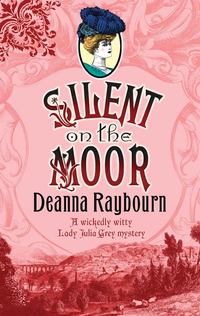

Silent on the Moor

But determination was not enough to silence my jangling nerves, and as I put the cup onto the saucer, I noticed my hand shook ever so slightly.

Just then, Jane returned. She resumed her place, giving me a gentle smile. “I do apologise about Puggy. He is not a very nice dinner companion. I have often told Portia so.”

“Think nothing of it. With five brothers I have seen far worse at table,” I jested. Her smile faded slightly and she reached for her glass as I fiddled with my teacup.

“I wish you were coming with us,” I said suddenly. “Are you quite certain your sister cannot spare you?”

Jane shook her head. “I am afraid not. Anna is nervous about her confinement. She says it will give her much comfort to have me in Portsmouth when she is brought to bed, although I cannot imagine why. I have little experience with such matters.”

I gave her hand a reassuring pat. “I should think having one’s elder sister at such a time would always be a comfort. It is her first child, is it not?”

“It is,” Jane said, her expression wistful. “She is newly married, just on a year.”

Jane fell silent then, and I could have kicked myself for introducing the subject in the first place. Anna had always been a thorn-prick to Jane, ever since their father died and they had been cast upon the mercy of Portia’s husband. Younger than Jane by some half-dozen years, Anna had made her disapproval of Jane’s relationship with Portia quite apparent, yet she had happily reaped the benefit when Portia had insisted upon paying the school fees to have her properly educated. Portia had offered her a place in her home, an offer that was refused with the barest attempt at civility. Instead Anna had taken a post as a governess upon leaving school, and within two years she had found a husband, a naval officer whom she liked well enough to enjoy when he was at home and little enough to be glad when he was abroad. She had settled into a life of smug domesticity in Portsmouth, but I was not surprised that she had sent for Jane. Few people were as calm and self-possessed, and I hoped that this olive branch on Anna’s part would herald a new chapter in their relationship.

I almost said as much to Jane, but she changed the subject before I could.

“Are you looking forward to your trip into Yorkshire?” she inquired. “I have never been there, but I am told it is very beautiful and unspoilt.”

“I am not,” I confessed. “I should like to see Yorkshire, but I am rather terrified to tell you the truth.”

“Brisbane?”

I nodded. “I just wish I knew. It’s all so maddening, the way he drops me entirely for months on end, then when we are brought together, he behaves as though I were the very air he breathes. Most infuriating.”

Jane put a hand over mine. Hers was warm, the fingers calloused from the heavy tools of her art. “My dear Julia, you must follow your heart, even if you do not know where it will lead you. To do otherwise is to court misery.” There was a fleeting shadow in her eyes, and I thought of how much she and Portia had risked to be together. Jane had been the poor relation of Portia’s husband, Lord Bettiscombe, and society had been cruel when they had set up house together after Bettiscombe’s death. They had a circle of broad-minded and cultured friends, but many people cut them directly, and Portia had been banned from the most illustrious houses in London. Theirs had been a leap of faith together, into a world that was frequently cruel. And yet they had done it together, and they had survived. They were an example to me.

I covered her hand with mine. “You are right, of course. One must be brave in love, like the troubadours of old. And one must seize happiness before it escapes entirely.”

“I will wish you all good fortune,” she said, lifting her glass. We toasted then, she with her wine, I with my tea, but as we sipped, we lapsed into a heavy silence. My thoughts were of Brisbane, and of the very great risk I was about to take. I did not wonder what hers were. It was only much later that I wished I had spared a care for them. How much might have been different.

THE SECOND CHAPTER

O mistress mine, where are you roaming?

—William Shakespeare

Twelfth Night

True to Portia’s intention, we left early the next morning, but we did not achieve Grimsgrave Hall by nightfall. The journey, in a word, was disastrous. Jane did not accompany us to the station, preferring instead to bid us farewell at Bettiscombe House. It was just as well, I thought. Between Portia and myself, there were two maids, three pets, and a mountain of baggage to be considered. Valerius met us on the platform, arriving just before the doors were shut and lapsing into his seat with a muttered oath and bad grace.

“Good morning, Valerius,” I said pleasantly. “How nice to see you. It’s been ages.”

The corners of his mouth were drawn down sullenly. “It was a fortnight ago at Aunt Hermia’s Haydn evening.”

“Nevertheless, it is good to see you. I know you must be mightily put out with Father for asking you to come—”

He sat bolt upright, clearly enraged. “Asking me to come? He didn’t ask me to come. He threatened to cut off my allowance entirely. No money, ever again, if I didn’t hold your hand on the way to Yorkshire. And worst of all, I am not permitted to return to London until you do. I am banished,” he finished bitterly.

Portia gave a snort and rummaged in her reticule for the timetable. I suppressed a sigh and gazed out the window. It was going to be a very long journey indeed if Val meant to catalogue his wrongs. The refrain was one I had heard often enough from all of Father’s younger sons. Although the bulk of the March estate was kept intact for Bellmont and his heirs, Father was extremely generous with his younger children.

Unfortunately, his generosity seldom extended to letting them make their own choices. They were expected to be dilettantes, nothing less than gentlemen. They might write sonatas or publish verse or daub canvases with paints, but it was always understood that they were strictly barred from engaging in trade. Valerius had not only struggled against this cage, he had smashed the bars open. He had at one time established himself, quite illegally, as physician to an expensive brothel. His dabbling in medicine had violated every social more that Father had been brought up to respect, and Father had very nearly disowned him altogether. It was only grudgingly and after a series of violent arguments that he had consented to permit Valerius to study medicine in theory, so long as he did not actually engage in treating patients. This compromise had made Val sulky, yet unsatisfactory as his work had become, leaving it was worse.

He lapsed into a prickly silence, dozing against the window as the train picked up speed and we began our journey in earnest.

Not surprisingly, Portia and I bickered genteelly the entire morning, pausing only to nibble at the contents of the hamper Portia’s cook had packed for us. But even the most delectable ham pie is no cure for peevishness, and Portia was in rare form. By the time the train halted to take on passengers at Bletchley, I had had my fill of her.

“Portia, if you are so determined not to enjoy yourself, why don’t you leave now? It can easily be arranged and you can take the next train back. A few hours at most and you can be in London, smoothing over your quarrel with Jane. Perhaps you could go with her to Portsmouth.”

She raised a brow at me. “I have no interest in seeing Portsmouth. Besides, what quarrel? We have not quarrelled.”

Val perked up considerably at this bit of news, and Portia threw him a vicious glance. “Go back to sleep, dearest. The grown-ups are talking.”

“Do not attempt to put me off,” I put in hurriedly, eager to avoid another squabble between them. “I know matters have not been right between you, and I know why. She is not easy about this trip. Perhaps she will simply miss your company or perhaps she fears you will get up to some mischief while you are away, but I know she does not like it. It does her much credit that she has been so kind to me when I am the cause of it.”

Portia wrapped the rest of her pie in a bit of brown paper and replaced it in the hamper. Val retrieved it instantly and began to wolf it down. Portia ignored him. “You are not the cause, Julia. I would have gone to Brisbane in any event. I am worried for him.”

My heart thudded dully in my chest. “What do you mean? Have you heard from him?”

She hesitated, then fished in her reticule. “I had this letter from him last week. I did not think to visit Grimsgrave so early. When he first invited me, I thought perhaps the middle of April, even May, might be more pleasant. But when I read that …” Her voice trailed off and I reached for the letter.

The handwriting was as familiar to me as my own, bold and black, thickly scrawled by a pen with a broad nib. The heading was Grimsgrave Hall, Yorkshire, and it was dated the previous week. I read it quickly, then again more slowly, aloud this time, as if by hearing the words aloud I could make better sense of them. One passage in particular stood out.

And so I must rescind my invitation to come to Grimsgrave. Matters have deteriorated since I last wrote to you, and I am in no humour for company, even such pleasant company as yours. You would hardly know me, I have grown so uncivilized, and I should hate to shock you.

I could well imagine the sardonic little twist of the lips as he wrote those words. I read on, each word chilling me a little more.

As for your sister, tell her nothing. She must forget me, and she will. Whatever my hopes may once have been, I realise now I was a fool or a madman, or perhaps I am grown mad now. The days are very alike here, the hours of darkness long and bleak, and I am a stranger to myself.

The letter dropped to my lap through nerveless fingers. “Portia,” I murmured. “How could you have kept this from me?”

“Because I was afraid you would not go if you read it.”

“Then you are a greater fool than I thought,” I replied crisply. I returned the letter to its envelope and handed it back to her. “He has need of me, that much is quite clear.”

“He sounds as if he wants to be left alone,” Val offered, blowing crumbs onto his lap. He brushed them off, and I rounded on him.

“He needs me,” I said, biting off each word sharply.

“It was one thing to arrive as my guest when I was invited,” Portia reminded me. “Does it not trouble you for both of us to arrive, unannounced and unwelcome? And Valerius besides?”

“No,” I said boldly. “Friends have a duty to care for one another, even when it is unwelcome. Brisbane needs me, Portia. Whether he wishes to own it or not.”

Portia’s gaze searched my face. At length she nodded, giving me a little smile. “I hope you are correct. And I hope he agrees. You realise he may well shut the door upon us. What will you tell him if he bids us go to the devil?”

I smoothed my hair, neatly pinned under a rather fetching hat I had just purchased the week before. It was violet velvet, with cunning little clusters of silk violets sewn to the crown and spilling over one side of the brim to frame my face.

“I shall tell him to lead the way.”

Portia laughed then, and we finished our picnic lunch more amiably than we had begun it. It was the last truly enjoyable moment of the entire journey. Delays, bad weather, an aimless cow wandering onto the railway tracks—all conspired against us and we were forced to spend an uncomfortable night in a hotel of questionable quality in Birmingham, having secured three rooms by a detestable combination of bribery and high-handed arrogance. Portia and I shared, as did the maids, and as penance for securing the only room to himself, Valerius was forced to spend the night with the pets.

After an unspeakable breakfast the next morning, we resumed our journey with its endless changing of trains to smaller and smaller lines in bleaker and bleaker towns until at last we stumbled off of a train hardly bigger than a child’s toy.

“Where are we?” I demanded. Portia drew a map from her reticule and unfolded it as I peered over her shoulder. Behind us, Morag and Minna were counting bags and preparing to take the dogs for a short walk to attend to nature.

Portia pointed on the map to an infinitesimally small dot. “Howlett Magna. We must find transport to the village of Lesser Howlett and from thence to Grimsgrave.”

Val and I looked about the tiny clutch of grey stone buildings. “There is something smaller than this?” he asked, incredulous.

“There is,” Portia said crisply, “and that is where we are bound.”

Portia was in a brisk, managing mood, and the arrangements for transportation were swiftly made. Valerius and I stood on the kerb surveying the village while Portia settled matters.

“It looks like something out of a guidebook of prospective spots to catch cholera,” Val said, curling his lip.

“Don’t pull that face, dearest,” I told him. “You look like a donkey.”

“Look at the gutters,” he hissed. “There is sewage running openly in the streets.”

I felt my stomach give a little lurch. “Val, I beg you—” I broke off, diverted.

“What is it?” Val demanded. “Someone bringing out their plague dead?”

I shook my head slowly. “No, there was a man walking this way, but he saw us and ducked rather quickly into the linen draper’s. I have never seen such a set of whiskers. He looks like Uncle Balthazar’s sheepdog. They are certainly shy of strangers, these Northerners.” I nodded to the doorway of the shop opposite. The fellow had been nondescript and rather elderly, wearing rusty black with a slight limp and a tendency to embonpoint. A set of luxuriant whiskers hid most of his face from view.

“Probably frightened away by how clean we are,” Val put in acidly.

I turned to him, lifting my brows in remonstrance. “You have become a thorough snob, do you know that? If you are so appalled by conditions here, perhaps you ought to do something to make them better.”

“I might at that,” he said. “God knows I shall have little enough to do in any case.”

There was an edge of real bitterness to his voice, and I suppressed a sigh. Val could be difficult enough when he was in a good mood. A peevish Val was altogether insufferable.

Portia signed to us then, her expression triumphant. The blacksmith at Howlett Magna had business where we were bound and agreed, for a sum that seemed usurious, to carry us, with maids, pets, and baggage, to the village of Lesser Howlett. From there we must make other arrangements, he warned, but Portia cheerfully accepted. She called it a very good sign that we had engaged transport so quickly, but I could not help thinking otherwise when I laid eyes upon the blacksmith’s wagon. It was an enormous, rocking thing, although surprisingly comfortable and cleaner than I had expected. In a very short time, we were settled, maids and bags and pets in tow, and I began to feel marginally better about the journey.

The countryside soon put an end to that. Each mile that wound out behind us along the road to Lesser Howlett took us further up into the great wide moors. The wind rose here, as plangent as a human voice crying out. Portia seemed undisturbed by it, but I noticed the stillness of Valerius’ expression, as though he were listening intently to a voice just out of range. The blacksmith himself was a taciturn sort and said little, keeping his attention fixed upon the pair of great draught horses that were harnessed to the wagon. They were just as stolid, never lifting their heads from side to side, but keeping a steady pace, toiling upward all the while until at last we came to Lesser Howlett.

The village itself looked grim and unhygienic, with a cluster of bleak houses propped against each other and a narrow cobbled road between them. A grey mist hung over the edge of the village, obscuring the view and making it look as though the world simply stopped at the end of the village road. We alighted slowly, as if reluctant to break the heavy silence of the village.

“Good God, what is this place?” breathed Valerius at last.

“The far edge of nowhere, I’d say,” came a sour voice from behind us. Morag. She was laden with her own enormous carpetbag as well as a basket for my dog, Florence, and the cage containing my pet raven, Grim. Her hat was squashed down over one eye, but the other managed a malevolent glare.

In contrast, Portia’s young maid, Minna, was fairly bouncing with excitement. “Have we arrived then? What a quaint little place this is. Will we be met? The journey was ever so long. I’m quite hungry. Aren’t you hungry, Morag?”

Portia, deep in conversation with the blacksmith, called for Minna just then and the girl bounded off, ribbons trailing gaily from her bonnet.

Morag fixed me with an evil look. “All the way, I’ve listened to that one, chattering like a monkey. I’ll tell you something for free, I shall not share a room with her at Grimsgrave, I won’t. I shall sooner lie down on this street and wait for death to take me.”

“Do not let me stop you,” I said graciously. I pinched her arm. “Be nice to the child. She has seen nothing of the world, and she is young enough to be your granddaughter. It will not hurt you to show a little kindness.”

Minna was a new addition to Portia’s staff. Her mother, Mrs. Birch, was a woman of very reduced circumstances, endeavouring to rear a large family on the tiny income she cobbled together from various sources, including washing the dead of our parish in London and laying them out for burial. Minna had always shown a keenness, a bright inquisitiveness that I believe would stand her in good stead as she made her way in the world. It had taken little persuasion to convince Portia to take her on to train as a lady’s maid. Our maids, Morag included, were usually taken from the reformatory our aunt Hermia had established for penitent prostitutes. It seemed a luxury akin to sinfulness to have a maid who was not old, foul-mouthed, or riddled with disease. I envied her bitterly, although I had grown rather fond of Morag in spite of her rough edges.

Portia at last concluded her business with the blacksmith and returned, smiling in satisfaction.

“The inn, just there,” she said, nodding across the street toward the largest building in the vicinity. “The innkeeper has a wagon. The blacksmith has gone to bid him to attend us to Grimsgrave.”

I turned to look at the inn and gave a little shudder. The windows were clean, but the harsh grey stone gave the place a sinister air, and the weathered signpost bore a painting of a twisted thorn and the ominous legend “The Hanging Tree.” I fancied I saw a curtain twitch, and just behind it, a narrow, white face with suspicious eyes.

Behind me, Valerius muttered an oath, but Portia was already striding purposefully across the street. We hurried to catch her up, Morag hard upon my heels, and arrived just as she was being greeted by the innkeeper himself, a dark young man with the somewhat wiry good looks one occasionally finds in the Gaels.

He nodded solemnly. “Halloo, leddies, sir. Welcome to tha village. Is i’ transport thee needs?”

Portia quickly extracted a book from her reticule and buried her nose in it, rifling quickly through the pages. I poked her sharply.

“Portia, the innkeeper has asked us a question. What on earth are you doing?”

She held up the book so I could read the title. It was an English phrasebook for foreigners. “I am trying to decipher what he just said.”

The innkeeper was staring at us with a patient air. There was something decidedly otherworldly about him. I noticed then the tips of his ears where his dark curls parted. They were ever so slightly pointed, giving him an elfin look. I smiled at him and poked my sister again.

“Portia, put that away. He is speaking English.”

She shoved the book into her reticule, muttering under her breath, “It is no English I have ever heard.”

“Good afternoon,” I said. “We do need transportation. We have been told you have a wagon—perhaps you have a carriage as well, that would be far more comfortable, I think. There are five in our party, with baggage and a few pets. We are guests of Mr. Brisbane.”

“Not precisely guests,” Portia said, sotto voce.

But her voce was not sotto enough. The innkeeper’s eyes brightened as he sniffed a bit of scandal brewing. “Brisbane? Does thou mean tha new gennelman up Grimsgrave way? No, no carriage will coom, and no carriage will go. Tha way is too rough. It must be a farm cart.”

Portia blanched and Morag gave a great guffaw. I ignored them both.

“Then a farm cart it will be,” I said firmly. “And do you think you could arrange such a conveyance for us? We are very tired and should like to get to Grimsgrave as quickly as possible.”

“Aye. ‘Twill take a moment. If tha’ll step this way to a private room. Deborah will bring thee some tea, and thee can rest awhile.”

Valerius excused himself to take a turn about the village and stretch his legs, but I thanked the innkeeper and led my dispirited little band after him upstairs to private accommodation. The inn itself was like something out of a children’s picture book. Nothing inside the little building seemed to have changed from the days when highwaymen stalked the great coaching byways, claiming gold and virtue as their right. Still, for all its old-fashioned furnishings, the inn was comfortable enough, furnished with heavy oak pieces and thick velvet draperies to shut out the mists.

The innkeeper introduced himself as Amos and presented a plump young woman with blond hair, Deborah, who bobbed a swift curtsey and bustled off to bring the tea things. We did not speak until she returned, laden with a tray of sandwiches and cake and bread and butter. A maid followed behind her with another tray for Minna and Morag, who perked up considerably at the sight of food. They were given a little table in the corner some distance from the fire, but Portia and I were settled next to it, our outer garments whisked away to have the dirt of travel brushed from them.

When the tea things had been handed round, Deborah seemed loath to go, and at a meaningful glance from Portia, I encouraged her to linger. We had not spoken of it, but it occurred to me—and doubtless to her as well—that it might be a good idea to glean what information we could from the locals about the state of affairs at Grimsgrave Hall.

For her part, Deborah appeared gratified at the invitation to stay. Her blue eyes were round in her pale face, and she refused Portia’s suggestion that she send for another cup and share our tea.

“I could not do tha,” she murmured, but she patted her little mob cap, and a small smile of satisfaction played about her mouth.

“But you must sit a moment,” I persuaded. “You must be quite run off your feet.” That was a bit of a reach. The inn was clearly empty, and although it was kept clean enough and the food was fresh and ample and well-prepared, there was an air of desolation about the place, like a spinster who was once the belle of the ball but has long since put away her dancing slippers and resigned herself to the dignity of a quiet old age.

Deborah took a small, straight-backed chair and smoothed her apron over her knees. She stared from me to Portia and back again.

“You seem terribly young to run such an establishment,” Portia commented. “Have you been married long?”

Deborah giggled. “I am not married, my lady. Amos is my brother. Will thou have another sandwich? I cut them myself.”

Portia took one and Deborah’s face suffused with pleasure. “I help him run the inn when we’ve guests.” She looked at us wistfully. “But thee’ll not stay here. Amos will take thee to Grimsgrave Hall.”

“Is the Hall a very old place?” I asked, pointedly helping myself to another slice of cake. The girl did have a very light touch. I had seldom had one so airy.