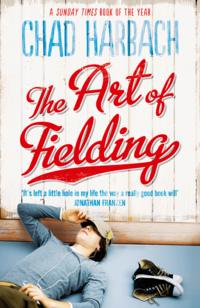

The Art of Fielding

“My name is Dr. Collins. Are you a relative of Owen Dunne?”

“Oh, no,” Affenlight said. “His family, actually, is from, um . . .”

“San Jose,” Henry said.

“Right,” Affenlight said quickly. “San Jose.” He’d felt such stupid pride at having the doctor call his name, as if he were the person nearest to Owen. The doctor turned to address herself to Henry:

“Your friend isn’t doing too badly, all in all. The CT showed no epidural bleeding, which is what we worry about in this kind of case. He has a severe concussion and a fractured zygomatic arch — that is, a cheekbone. His functions appear normal. The arch will require reconstructive surgery, which I imagine we’ll try to do right away, as long as we’ve got him here.” Dr. Collins, who despite the purple fatigue marks under her eyes looked no older than twenty-five, paused to pluck at the V of her scrub top, above which her skin was Irishly pink and mottled. Affenlight saw, or imagined he saw, her tired eyes settle on Henry in an interested way.

“Can I see him?” Henry asked.

Dr. Collins shook her head. “His concussion’s pretty severe, and we’re going to keep him in the ICU tonight. He seems to be suffering some short-term memory loss, which we assume will clear. Tomorrow you can see him all you like.” She patted Henry consolingly on the arm.

Affenlight’s cell phone shivered against his thigh. The number was unfamiliar, with a 312 prefix, but he knew who it would be. He made an apologetic gesture toward the doctor, who didn’t notice, and walked into the hall. “Pella. Kiddo. Where are you?”

“Chicago. I made my connection. We’re about to board, so I should be right on time.” Her voice sounded thin and crackly through the pay-phone static. “I thought maybe we could go to Bau Kitchen.”

This was Pella’s favorite restaurant in Milwaukee, the place where they’d celebrated her sixteenth birthday. If Affenlight had been zipping down I-43 toward the airport, an Italian opera tucked into the Audi’s CD player, he would have been heartened by this suggestion, which seemed like a gesture of peace. Instead he was bound to be late, and he couldn’t help wondering whether Pella had already sniffed out his neglect, or what was bound to seem like neglect, and had decided to punish him with solicitude. “That’s a wonderful idea,” he said. “But I’m afraid I’m running a little late.”

“Oh.”

Disappointment, fragility, the phrase picking up where we left off— these things and more came streaming through the phone line’s silence. “I’m at the hospital,” Affenlight said, trying to ward them off. “We’ve had an accident at the school. I’ll be there as soon as I can.”

“Sure,” Pella said. “Whenever.”

As he hurried out, Affenlight paused long enough to buy a pack of cigarettes — Parliaments, his old standby — from the hospital gift shop. A hospital that sold cigarettes: he rolled this notion in his head, wondering whether it spelled doom or hope, while he thrust a twenty at the gray-haired woman behind the counter. He shoved the pack in his pocket and tried to leave without his change, but she summoned him back and insisted on counting out, with excruciating and perhaps remonstrative slowness, a ten, five ones, and several coins. Coach Cox drove him to his car, and he rocketed down the empty interstate, Le Nozze di Figaro blasting, windows down.

Chapter 10

Pella left San Francisco with only a floppy, cane-handled wicker bag that contained whatever remained from her last trip to the beach nine months ago, a useless assortment of crap — sunglasses, tampons, gummy worms, sand — to which she’d added nothing but her wallet and a black bathing suit, designed for serious swimming.

As the plane slipped up the narrow industrial corridor that connected Chicago to Milwaukee, the darkness of Lake Michigan spread beyond the starboard windows, she was already beginning to regret not having packed a suitcase. It was the kind of overly emphatic gesture she was famous for, at least in her own mind, and should have outgrown by now. Maybe she’d thought it would make the break with David cleaner, easier, more decisive: See, I don’t need you. I don’t need anything. Not even underwear. She hadn’t bothered to remember that there was nowhere decent to shop near the so-called city of Westish, Wisconsin.

How stupid she felt, to feel this bad, to feel her life lying around her in ruins, and yet to have no story to tell about it. Sure, in some abstract sense it was a story, or would someday become one . . . Yes, I was married once. I dropped out of high school, ran off with an architect who’d come to lecture at my prep school. I was a senior, had just turned nineteen. David was thirty-one. At the end of his week at Tellman Rose, I slept with him. One of us was going to sleep with him, and as the reigning alpha female I had first dibs. I had dated older guys — high school guys when I was in junior high, college guys when I was at Tellman Rose, a few starving-artist types on trips to Boston or New York — but David was something new to my experience. A man, full stop.

A bit of a weenie, perhaps — petulant, conniving, prim. But that’s a retrospective analysis. At the time I just saw the charm and cultivation, the dark twinkling eyes above the brown beard, the immense learning. And more than those things, I saw the virtue. He was a man who lived by a code. He thought classical learning was important, and so he’d become an excellent classical scholar, though it was only indirectly useful to his practice. Which was itself a model of virtue: an attempt to create classically beautiful buildings that were, you know, green. This wasn’t a man who watched TV, went to the gym, wasted time. He didn’t eat meat and he drank only to show off his knowledge of wine.

I was attuned to his every move as he delivered his afternoon lectures, as he held forth at various luncheons and dinners, to which I always managed to be invited. Clearly I had a daddy thing going on, even more than usual. He possessed the three qualities I associated most closely with my father — learned, virtuous, flummoxed by me — and he displayed them all much more conspicuously, not to say pretentiously, than my dad ever had. My dad was cool. David was like my dad but not cool at all. One of the TR girls, not my main rival but the one I feared most, because she was as smart as I was, referred to me as Pellektra. I couldn’t complain; it was too spot-on, her tone too light. You’re only Jung once, I replied. Enjoy it.

Because of David’s virtue, his virtuous self-image, I had to present myself as the seducer. Which I did, a project that culminated the night before his departure. I felt as if I’d deflowered him, not because he was inept compared to other guys — again, he was thirty-one — but because he maintained that facade of virtue until the last. You’re awfully stiff, I said right before we kissed — my last best double entendre of the night.

A week later was spring break. I’d just gotten into Yale. My friends and I were going to Jamaica to drink. We were at the Burlington airport, already drinking. David walked in. He had a bag over his shoulder, two tickets to Rome in his hand. Shall we? he said. He was sweating, plotting, a turtleneck under his jacket, anxious about my answer — not cool.

My break was a week long, but we stayed in Rome for three. Afterward we flew to San Francisco, where David’s latest project was located; I felt elated, like I’d bypassed Yale and young adulthood and graduated straight into the world. When I recall those first weeks with David among the crumbling buildings of Rome, weeks of feeling deliciously older than old, giddy with my own seriousness, it’s probably no accident that I can’t think of my life without using the word ruined.

Pella, per instructions, finished her whiskey and returned her seat back to the upright position. Okay, you could tell that part like a story, a creative-writing assignment, could even toss in a florid last line to keep people on their toes, but that was because it wasn’t the real story. By which she meant it wasn’t an answer to the questions she feared most: Who are you? What do you do? Well, what do you want to do?

No, the past four years — and especially the last two — had passed in something like a dream, and nobody wanted to hear about your dreams. She’d done nothing. At some point she’d realized that the marriage was a mistake, but she’d been unable to admit it to herself. She’d cut herself off from the source of her distress, which happened to be her entire life. Consequently she became helplessly depressed, and David hadn’t minded, because when she was helplessly depressed she depended on him and was therefore unlikely to leave him for someone her own age, which was always his greatest fear.

And so the months had mounted, Pella lying in bed in their sun-struck loft, dragging herself to the Rite Aid and the psychiatrist and back again, David alternately peeved and given purpose by her somnolence. There were events, fights, excursions, but none of it mattered, none of it penetrated the thick fog under which she lived. I ruined my life in Rome and lived in a fog in San Francisco. Their sex life dwindled, and neither of them mentioned it. “They” were fine. She had to get better. Why was one in quotes and not the other? David prescribed regimens to help her sleep at night: no caffeine, no TV, no electric lights. Each night she would go to bed beside him and then, the instant his breathing changed, get up and go to the kitchen to begin her nightly vigil of slowly drinking whiskey and chewing sunflower seeds while enduring the sheer excruciating boredom of being alive.

Eventually, inevitably, she’d landed in the hospital, with heart palpitations from the mix of drugs she was taking—over-the-counter sleep aids, antianxietals, prescription painkillers, in almost random configurations, in addition to the whiskey and her antidepressants. In the hospital they put her on suicide watch. She hadn’t been trying to kill herself, though that was easy to say in retrospect, now that she felt a tiny bit better. Her thinking about death had always been inextricable from her thinking about her mom; there was pain and pleasure, fear and comfort there, mixed in roughly equal parts. “It’s the Affenlight men who die young,” her dad had said long ago, in a weird attempt to reassure the nine- or ten-year-old daughter he’d never quite known what to do with. “The women live forever.” Though this had been borne out in particular historical cases, she couldn’t believe it applied to her or, God forbid, to him. It was hard to imagine her father as anything but immortal, her own purchase on the world as anything but tenuous.

Not long after the hospital incident she’d been given a new, experimental SSRI — a tiny sky-blue pill called Alumina, presumably to connote the light it would bring into your life, though Pella couldn’t help seeing the word Alumna and interpreting it as a snide remark on her failure to finish high school. She Sharpied out the label and called it her sky-blue pill. But it worked, it worked, better than anything ever had. She started to read again. She felt a little better; she was able to think about her life. It was confusing to have leaped precociously ahead of her high-achieving, economically privileged peers by doing precisely what her low-achieving, economically unprivileged peers tended to do: getting married, staying home, keeping house. She’d gotten so far ahead of the curve that the curve became a circle, and now she was way behind.

In recent months, her panic attacks came less often and lasted less long. After David fell asleep she bundled up and went out on their plant-filled terrace with a flashlight and sat in a lawn chair and read through the chilly San Francisco night, downtown and the bridges twinkling in the distance. She could feel her strength slowly returning, being marshaled for some maneuver or another; she didn’t know what it was. Then at five o’clock Tuesday morning, David in Seattle on business, she found herself dialing her dad’s number. She hadn’t seen him since she met David, hadn’t spoken to him since Christmas.

Pella chomped her gum as the plane descended. Then she headed for the baggage claim, not because she had any baggage — except for that failed marriage, kaching! — but because that was where she and her dad used to meet, when she made trips from Tellman Rose. She stretched out across three plastic chairs and watched the carousel mouth disgorge a series of compact black bags with wheels. Her dad had said he’d be late — how dully typical of him — but he hadn’t said how late. The black bags all disappeared, were replaced by a new set from a new flight, and then another. Was there an airport bar nearby? Probably, but she was too tired to look. It saddened her that her dad was willing to start on this note. The carousel bags blurred together, and she closed her eyes.

“Excuse me,” said somebody, somebody male. The guy smiled suavely. “You probably shouldn’t fall asleep here,” he said. “Somebody might steal your bag.”

“I wasn’t asleep,” Pella said, though clearly she had been.

The guy smiled some more. Everyone’s teeth were so white these days, even in Milwaukee. He gestured to the carousel. “Can I help you with your bags?”

Pella shook her head. “I like to travel light.”

The guy nodded intently, as if this were the most fascinating thing he’d ever heard. He held out his hand, introduced himself. Pella told him her name.

“My, what a lovely name. Is that British?”

“Wull I don’t rightly know, luv,” she said in her worst Cockney. “Would ya like it ta be?”

The guy’s brow furrowed, but he recovered. “So. Where are you headed?”

“Home.” What was it with guys in suits? They acted like they ran the world. Pella saw her dad striding through the long concourse, tie dangling. “And there’s my fiancé now,” she said.

The guy looked up at the approaching late-middle-aged man, back at Pella. His brow furrowed again. He’d wind up with wrinkles. “You’re not wearing a ring,” he pointed out.

“You’ve got me there.” Her dad looked wounded, disoriented, lost — he was about to walk right past when Pella leaned out and plucked at his sleeve. “Hey,” she said. Her heart was hammering away.

“Pella.” They faced each other, separated by one final yard of fibrous blue carpeting. Four years. Pella fiddled with her sweatshirt zipper. Her dad’s forearms lifted from his sides in an apologetic, almost helpless gesture of welcome, palms upturned. “Sorry I’m late.”

“That’s okay.” Obviously there was an evolutionary advantage to thinking your own family attractive — it made the members more likely to protect one another against outside threats — but Pella couldn’t imagine anyone failing to find her father handsome. He’d entered his sixties, a decade usually associated with decline — but apart from a weary confusion in his eyes, he looked just as she remembered, his thick gray hair streaked with silver, his skin mahogany-ruddy in that way that lent credence to rumors of Native American ancestry, shoulders as square and upright as a geometry proof.

“The prodigal daughter,” she said as they embraced in a quick, stiff clinch.

“You’ve got that right.”

Pella sniffed his neck as they separated. “Have you been smoking?”

“No, no. Me? I mean, I might have had one in the car. It’s been a long day, I’m afraid . . . Do we need to collect your luggage?”

Pella frowned at her wicker bag. “Actually, this is all I brought.”

“Oh.” Affenlight had been hoping she might stay for a while; the ticket, after all, had been one-way. But a lack of luggage didn’t bode well. He didn’t dare ask; better to enjoy the present. Perhaps if the question of leaving never came up, she’d forget to want to leave. “Well then. Should we hit the road?”

I-43, after passing through the northern Milwaukee suburbs, cut due north through vast stretches of flat, yet-unplanted fields. Clouds obscured the moon and stars, and the southbound traffic was sparse. Off to the right lay Lake Michigan, invisibly guiding the highway’s course. Pella expected an immediate grilling—How long are you staying? Have you broken up with David? Are you going back to school?—but her father seemed anxious and preoccupied. She wasn’t sure whether to feel relieved or insulted. They spent most of the ride in silence, and when they spoke, they spoke in monosyllables, more like characters in a Carver story than real live Affenlights.

The president’s quarters, cozily appointed in academia’s dark wood and leather, were located on the uppermost floor of Scull Hall, in the southeast corner of the Small Quad. The Westish presidents of the twentieth century had all lived downtown, in one or another of the elegant white houses that flanked the lake, but Affenlight, the first president of the twenty-first, had decided to revive the quarters’ original purpose and reside among the students. It was just him, after all. This way his office lay just a staircase away from his apartment, and he could sneak down at dawn for a quiet stint of work, dressed in whatever, before Mrs. McCallister arrived and the day’s appointments began.

He poured them each a whiskey, his with water, Pella’s without. “I suppose this is legal now,” he said as he handed her the glass.

“Takes half the fun out of it.” Pella arranged herself in a square leather chair, drew her knees up to her chest. “So how’s business?”

Affenlight shrugged. “Business is business,” he said. “I don’t know why they keep hiring English professors for these jobs. They should get guys from Goldman Sachs or something. If I have ten minutes a day to think about something besides money, I consider myself lucky.”

“How’s your health?”

He drummed on his sternum. “Like a bull,” he said.

“You’re taking your medicine?”

“I take my walk by the lake every day,” Affenlight said. “That’s better than medicine.”

Pella gave him a distressed maternal look.

“I take them,” he said. “I take them and take them. Though you know how I feel about pills.”

“Take them,” Pella said. “Are you seeing anyone?”

“Oh. Well . . .” Seeing, actually, was just the word for it. “Let’s just say there aren’t many enthralling women in this part of the world.”

“If there are any, I’m sure you’ll hunt them down.”

“Thanks,” Affenlight said dryly. “And you? How’s David?”

“David’s fine. Although he’ll be less so when he finds out I’m gone.”

“He doesn’t know you’re here?” This revelation trumped the lack of luggage; Affenlight resisted the urge to stand and pump his fist.

“He’s in Seattle. On business.”

“I see.”

Lately it seemed to Affenlight that the students were growing younger; maybe he was just getting old, or maybe adolescence was stretching out longer and longer, in proportion with the growing life span. Colleges had become high schools; grad schools, colleges. But Pella, as always, seemed intent on shooting ahead of her peers. She looked older than he remembered, of course — her cheeks less round, her features more pronounced — but she also looked older than twenty-three. She looked like she’d been through a lot.

“Are you tired?” he asked, remembering not to say You look tired.

She shrugged. “I haven’t been sleeping much.”

“Well, the bed in the guest room is great.” Mistake: he should have said your room. Or would that have seemed too eager? Anyway, onward: “And the darkness out here is something to behold. Totally different from Boston. Or San Francisco.”

“Great.”

“You can stay as long as you like. Of course.”

“Thanks.” Pella finished her whiskey, peered into the bottom of her glass. “Can I ask one more favor?”

“Shoot.”

“I’d like to start taking classes.”

“You would?” Affenlight stroked his chin and considered this happy news. “That should work out fine,” he said, trying to keep his tone as neutral as possible; to betray too much enthusiasm might backfire. “The deadlines for the fall have passed, of course, but you can register for the summer session as a visitor, and if we sign you up for the next SAT date, I’m sure I could convince Admissions —”

“No no,” Pella said quietly. “Right away.”

“What’s that?”

“I . . . I was hoping I could start right away.”

“But, Pella, the summer is right away. It’s already April.”

Pella chuckled nervously. “I was thinking about tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow?” Every nerve in Affenlight’s spine quivered, half with love of his daughter, half with indignation at her presumption. “But, Pella, we’re halfway through the semester. Surely you can’t expect to hop right in.”

“I could catch up.”

Affenlight set down his drink, drummed his fingers on the arm of the chair. “I don’t doubt that you could. You’re an excellent student when you choose to be. But it’s not simply a matter of catching up. It’s a matter of courtesy. As a professor, I can tell you I wouldn’t be pleased to be suddenly told —”

“Please,” Pella said. “I could just audit. I know it’s not ideal.”

Those first two years after Pella’s mother died: call them an adjustment period. He tried day care — expensive day care — but as soon as Affenlight grew accustomed to the fact that Pella was his, the sons and daughters of his fellow professors seemed like wan, elitist company. Better to throw her in with hoi polloi, to let her lift them up — but no, that would be even worse. He’d wanted to take her to another country, Italy, or Uganda, or somewhere, where it might be possible to raise her properly; he wanted to buy a tract of land in Idaho or Australia, with hills and streams and trees and rocks and birds and mammals, where Pella could roam and explore and he could trail behind, watching her grow; alternately he wanted to drop her at an orphanage and get back his life.

But something happened, to her and to him, when Pella learned to read. He would struggle out of bed after a late night’s work to find her already awake and dressed, in the breakfast nook of their townhouse on Shepard Street, reading from some or another novel — Judy Blume, Trixie Belden, her abridged Moby-Dick — or else some picture-laden science book culled from the stacks of Widener. She read with colored pencil in hand, copying the best sentences and sketching members of her favorite phyla onto sheets of construction paper. A few last Cheerios, floating in a bowl beside her elbow, impressed Affenlight as symbols of utter independence.

When interrupted by a polite paternal throat-clearing, Pella would look up from her book and wipe a coppery curl from her eyes, her expression oddly reminiscent of the one Affenlight’s dissertation adviser would assume when Affenlight appeared unannounced at his office door, and that Affenlight always thought of as studius interruptus. Still groggy and somewhat cowed by his daughter’s industry, he would tousle her hair, start the coffee, and head back to bed. If the school authorities wanted her that badly, he reasoned, they could come a-knocking.

The next half dozen years were halcyon ones for Affenlights père et fille. The Sperm-Squeezers went through several reprints. Pella became a perpetual truant from the Cambridge public schools, and a kind of Harvard celebrity. She wandered the Yard with her backpack, handing out sketches and poems to the students who stopped to chat. The members of each new freshman class, neurotically eager to compete with one another in any and all endeavors, fought mightily for Pella’s affection, and within the Freshman Union it became a mark of status to have her at your lunch table. She sat quietly through Affenlight’s packed lectures on the American 1840s, as well as his graduate seminar on Melville and Nietzsche, and she seemed to draw few distinctions between herself and the graduate students, except that the graduate students were forever eager to please Affenlight, whereas she did so without effort, and so could afford to think for herself.

When Affenlight took the job at Westish, he and Pella decided that she would not come with. Instead she enrolled at Tellman Rose, an unconscionably expensive boarding school in Vermont. Academically, this made sense; Pella was finishing eighth grade at the time — around age eleven she’d started attending Graham & Parks every day — and Tellman Rose was far superior to any high school in northern Wisconsin. But beneath that rationale lay the obvious, unspoken truth that the two of them, by that point, could barely coexist in Boston, and Affenlight shuddered to think what would happen in a foreign, isolated place like Westish. Most of Pella’s friends were older, and she claimed their freedoms for herself. She came home later and later at night, sometimes so late that Affenlight couldn’t stay awake to see what was on her breath.