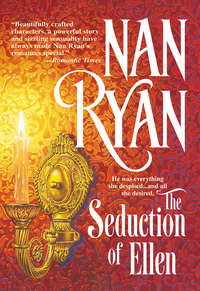

The Seduction Of Ellen

Then closed her eyes and sighed and squirmed and daydreamed and pretended that she was someone else and he was someone else and that the two of them were madly in love and could hardly bear being parted from one another, even for a few short days.

At the end of her allotted half hour, Ellen’s blood had cooled and her equilibrium had returned. She was herself again, a wise, sedate, rational woman who placed the book in her reticule where it belonged.

She also placed Mister Corey where he belonged.

Out of her thoughts.

Ellen was weary.

Tired to the bone.

She had been sitting up all night and all day in an uncomfortable wooden day chair and her back was aching mercilessly.

But her exhaustion magically departed when, less than twenty-four hours after leaving New York City, the train began traveling across the beautiful South Carolina lowlands toward the coastal city of Charleston. Hardly able to contain her excitement, Ellen lowered the window to look out. She inhaled the heavy, humid air and could have sworn it carried the faint scent of magnolias. Soon she could see the tall spire of St. Michael’s Church. Her heart raced. She was almost there.

Ellen considered Charleston, South Carolina, to be a beautiful, unique, seductive city, unlike any other. The city proper was built on a peninsula between two rivers, the Ashley and the Cooper, which flowed together to form the busy Charleston harbor. The earliest settlement in South Carolina, it was an enchanting, semitropical city where gracious living prevailed, good manners were requisite and some of America’s oldest, wealthiest families lived.

The pace was much slower here than in New York City. The content Charlestonians took the time to enjoy life’s pleasures and the pleasures were many. Chris had told her that Charleston was often referred to as an American Venice by the proud citizens. And she knew why.

The train was fast approaching the downtown depot. It was nearing three in the afternoon. In less than one hour she would see her son. When she’d wired Chris that she was coming, he had wired her back, saying, apologetically, that he would be unable to meet her at the station. It was a long-standing tradition that Fridays at 3:45 was parade at the academy and all the corps marched. His general leave wouldn’t start until 5:00 p.m. Then he would be free until midnight.

Ellen was glad he wouldn’t be at the station. She knew she looked a sight and she wanted to freshen up and change clothes before she saw her son or his friends.

She didn’t want Christopher to be ashamed of his mother.

Seven

Ellen hired a carriage to take her to the Mills House on Meeting Street. Chris had made reservations for her at the imposing five-story hotel in downtown Charleston a few short blocks from the harbor.

As the uniformed doorman stepped forward to help her down from the carriage, Ellen asked the cabdriver if he would kindly wait and drive her to the Citadel. She wouldn’t, she promised, be more than fifteen minutes. The driver agreed.

Once inside her fifth-floor room, Ellen went hastily about throwing open the windows. She paused before one for a moment and looked out, viewing the Battery and the sailing vessels on the calm waters of the Ashley River. And out in the harbor, the big parrot guns of Fort Sumter, that historic place where the War Between the States had begun.

It had been, legend claimed, cadets from the military academy her son now attended who had opened fire on a Northern supply ship attempting to deliver supplies to the garrison at Fort Sumter. The first shots fired in the war.

Ellen turned away.

She didn’t want to think about war and destruction. She wanted to dwell entirely on the next two carefree days she would be spending with her son.

Humming happily, Ellen took a hurried bath, redressed her long chestnut hair neatly atop her head and put on her best summer frock, a sky-blue poplin with elbow-length mutton-chop sleeves, tight waist and narrow skirt that flared at the knee. Taking one last appraising look in the mirror, Ellen frowned and sighed. She certainly wouldn’t win any beauty prizes. Her cheeks were too hollow, her complexion too sallow, her hair too dull.

She turned away, grabbed her gloves and reticule, rushed downstairs, out onto the street and up into the waiting carriage.

“The military academy,” she said. Then, unable to keep her maternal pride to herself, she added, “My son is a cadet at the Citadel.”

“Is he now?” the cabbie responded, then drove several long blocks down Meeting Street until he reached the section of the old rampart called Marion Green. Once a state arsenal and guardhouse, it was now the remodeled, three-story Citadel.

Quickly paying the fare, Ellen was out of the carriage with the agility of a young girl. She was ushered through the gate and onto the academy grounds by the Cadet Officer of the Guard.

Her heart aflutter, Ellen hurried toward the parade ground to join other visitors and natives who were watching the South Carolina Corps of Cadets marching in full-dress parade. Ellen stood at the perimeter of the quadrangle with the other onlookers, shading her eyes against the strong Carolina sun, searching a sea of bright young faces for the one dear to her heart.

The marching cadets wore their crisp summer whites. The tight-fitting waist-length jackets with their stiff stand-up collars had a triple row of brass buttons adorning the chest. The neatly pressed trousers had gold stripes going down the outside of each leg. Those stripes were now moving as one, as feet were lifted and lowered in flawless cadence by the well-trained cadets.

On their heads were tall, plumed hats with chin straps worn just below their noses. The cadets’ white-gloved hands swung back and forth in perfect precision. They were, Ellen thought, America’s finest sons and her heart swelled with happiness at the knowledge that her own precious son was one of their elite number.

Awed, she watched the proud corps pass in review while the regimental band played and the crowd of visitors applauded and waved American flags. Ellen continued to anxiously hunt for Chris. Finally she spotted him. Her hand went to her breast and she exhaled with pleasure.

Christopher marched with the skill and expertise of one who’d spent many long hard hours on the parade ground. His back was rigid, his shoulders straight, chest out, stomach in. He was staring straight ahead. Lean. Proud. Erect.

A true cadet.

When the dress parade ended, Ellen stayed where she was. She spotted Chris looking about and knew that he was hunting for her. She raised a hand and waved. He caught sight of her and a wide boyish smile instantly spread across his face. He yanked off his plumed hat and started running toward her, dodging other cadets as he came.

Ellen didn’t move. Just stood there admiring him as he sprinted toward her. Tall and blond and incredibly handsome in his crisp summer whites, he was the precious child of her heart, the light of her life, the one thing in this often dark, dismal world that had made it all worthwhile. The mere sight of him coming toward her erased all the pain and loneliness she’d ever known. The brilliant sun in her universe, he was, and always had been, the sweetest, kindest, most loving child in the world.

But he was no longer a child, she realized almost sadly as she watched him approach. He was no longer her little boy. He was no longer a boy. That nervous, slender eighteen-year-old who had entered the academy last autumn was gone. In his place was a sleek, efficient, confident young man.

Chris reached his mother, threw his arms around her, lifted her off the ground and swung her round and round while she laughed, somewhat embarrassed.

Chris Cornelius was the opposite of Ellen. Where she was by nature prim, sedate, timid, submissive and distrustful, her only son was gregarious, friendly, trusting, outgoing and fun-loving.

When at last Chris put Ellen down, he gave her an affectionate kiss on the cheek, not caring who saw, and said honestly, “I’m glad to see you, Mother.”

“I’ve missed you so,” she softly replied. She drew back to look up at him. “You’ve grown,” she said as if surprised. “You’re taller than you were at Christmas break.”

“I have,” he said proudly, “Guess how tall I am.”

“Six foot?”

“Six-one,” he said, laughing. “Come on, I want to introduce you to my friends.”

“Are you sure?” Ellen asked hesitantly. “I don’t look my best after all those hours on the train.”

Chris’s blond eyebrows shot up. “Aunt Alex didn’t let you come down in the rail car? You had to sit up in a day coach the entire way?” Ellen nodded sheepishly. His brilliant blue eyes momentarily flashed with anger, then he quickly smiled again and said, “I sure hope God threw away the pattern after he made her, don’t you?” Ellen laughed. Chris laughed with her, squeezed her waist and said, “Mother, you look beautiful. Let’s go meet my friends.”

Chris introduced Ellen to his roommates, three young men who had been through the grueling plebe year with him. They were mannerly, attentive, and made easy, amiable small talk.

After several minutes of pleasantries, Ellen said, “I’ve heard the first year at the academy can be quite difficult.” She smiled at Pete Desmond, a big, muscular cadet from Richmond, Virginia, and said, “Tell me, were the upperclassmen mean to you knobs?”

Pete glanced at Chris, who stood behind his mother. Chris shook his head. Pete grinned and said, “No, ma’am, Mrs. Cornelius. They were most helpful and kind.”

Ellen didn’t believe Pete. She had heard the stories of how the upperclassmen at military academies were sometimes quite brutal to the plebes. She had worried about Chris since the day he had come here, had wondered what he was going through.

“You hear that, Mother? What did I tell you?” Chris said.

Chris, not wanting to worry her, had never told his mother of the demeaning torment and physical misery he had suffered at the hands of some sadistic upper-classmen. He had never once, in his weekly letters, mentioned his agonizing loneliness, his intense fear, his constant exhaustion. His biggest fear had been that he would be branded a coward and drummed out of the corps like so many others who had come here with high hopes, only to be sent home in shame.

He never would tell her.

He had made it.

The first year was almost over and he had survived the rigors of the institute and had never complained, except to the three cadets who were his roommates. They had been through the torture with him. They had shared his terror and had understood his fear. They had comforted him when he was in danger of breaking and he had done the same for them. The experiences they had shared had drawn them closer than brothers. The four of them were good friends. The best of friends. Chris loved these three brave, loyal men with whom he had been through the fires of hell. He knew that they would be his friends for life.

Chris invited the roommates to join his mother and him for dinner that evening, but they respectfully declined.

Jarrod Willingham, a slender, red-haired, freckle-faced cadet from Memphis, Tennessee, said, “We do appreciate the invitation, Chris, but I know if my mother came to visit, she’d want to have me to herself for a while.” Jarrod grinned and winked at Ellen.

Ellen smiled and nodded.

The visit to Charleston was everything Ellen had hoped for and more. After an excellent dinner that evening, she and Chris strolled toward the Battery in the bright Carolina moonlight. Their pace leisurely, their conversation inconsequential, they soon reached South Battery and continued beneath the tall oaks to the seawall.

Chris took Ellen’s hand as they ascended the steps of the seawall. At the top, they stood in silence for a time before the railing, watching the glittering lights of houses along the shore of James Island and listening to the unique sounds of the sea.

The tide was going out. The powerful beams of the moon were now in command of the ocean’s current. It was a warm, beautiful, starry night, perfect for promenading along the old seawall.

Deeply inhaling the heavy, moist air, Chris said, “It’s nice here, isn’t it, Mother?”

“Mmm,” she murmured. “Breathtaking. I wish I could spend the rest of my life here.”

Chris laughed. “You don’t mean that.”

“Oh, but I do. I would love to live in these warm lowlands near the ocean.”

“Who knows? Maybe someday you will,” Chris offered. Left unsaid was that it would have to be after Alexandra had passed away.

“Perhaps,” she said dreamily, not really believing it.

On leaving the seawall, they walked down the Battery to East Bay and Chris pointed out the stately mansions on the tree-shaded streets South of Broad, where the aristocracy resided.

“The old Charleston families dwell in these houses,” Chris told his mother. “I know a couple of cadets who came from here.”

Although she had been raised around great wealth, and presently lived in an opulent town house, Ellen was awed by these splendid southern residences that were guarded by ancient towering oaks and surrounded by lush, verdant gardens. It was the gardens that most impressed her. Accustomed to the starkness of the plain concrete sidewalk outside the Park Avenue town house, she was enchanted by the profusion of flowers and leafy vines and velvet lawns before her.

“This incredible garden,” she enthused, gazing at one particularly well-tended, flower-filled terrace sloping down to the street. “These grounds must be the most beautiful in the entire state of South Carolina.”

“They are exquisite, but you should see Middleton Place,” Chris said offhand. A pause, then, the idea abruptly striking him, he said, “How would you like to see Middleton Place, Mother? It’s an old, uninhabited plantation that was once one of the glories of the Low Country. The gardens and ponds are still there. Would you like to see them?”

“I would love to see them.”

“Tomorrow at noon, as soon as general leave starts, I’ll hire a carriage and we’ll drive out into the country. You have the hotel pack us a picnic lunch and we’ll make a day of it.”

“I can hardly wait.”

The ride out into the lush, green countryside of South Carolina was highly enjoyable for Ellen. Along the narrow dirt road, tall pines grew and several bountiful orchards were filled with blackberries, grapes, persimmons and plums. Birds sang sweetly in the trees and the occupants of passing carriages waved as if greeting old friends.

It was early afternoon when the pair reached Middleton Place on the banks of the Ashley River. Ellen was eager to explore the estate and Chris was only too happy to point out where the plantation house had once stood. He told her the home had been built in the mid 1700s in the style of an Italian villa.

“What happened to it?” Ellen asked. There was nothing there but a pile of rubble.

“A detachment of Sherman’s army occupied the plantation in the war. When it was time to move on, the soldiers ransacked the house, then set it on fire. Then the walls finally fell in the earthquake of ’86.”

“Such a shame,” said Ellen.

“Yes,” Chris agreed, “but the gardens are still here and someone—I don’t know who—tends them regularly. Come.”

Chris showed Ellen the most magnificent grounds that she’d ever imagined. Classical in concept, geometric in pattern, the gardens featured parterres, vistas, allées, arbors and bowling greens. And everywhere, among the live oaks and Spanish moss, was water, reflecting in its depths the clear Carolina sky.

There were broad-terraced lawns and butterfly lakes and a rice mill pond. Azaleas and magnolias and camellias in full bloom sweetened the air with their fragrance.

Chris told his mother the history of the house and its family while they ate cold chicken and ham and cheese and rolls as they sat on a blanket in the shade of a tall oak.

Feeling lazy after the meal, they stretched out on their backs to talk and doze and enjoy the serenity and beauty of the warm May afternoon. A time or two Ellen considered telling Chris about the upcoming adventure—or misadventure—that Alexandra had planned. But she didn’t want to spoil this perfect spring day. She would tell him tomorrow.

On Sunday, Ellen and Chris attended church services at St. Michael’s. Afterward they had lunch in the Mills House dining room. It was during the meal that Ellen told her son of Alexandra’s latest folly.

“Chris, you know that Aunt Alexandra hates the idea of getting old,” she began.

Chris laughed and said, “Somebody should tell her that she’s already old.”

His mother smiled, then was serious. “I know. But she doesn’t want to get any older, so…”

Ellen drew a deep breath and related the entire story. She told him that Alexandra had been furious with the physicians in London when they’d told her there was nothing they, or anyone else, could do to slow down the aging process. That she was an old woman and couldn’t expect to live many more years.

Ellen went on to explain that Alexandra had seen an ad in the newspaper promising magic waters that would keep a person forever young. Ellen talked and Chris listened intently, seeing the worry in her eyes.

When her story was finished, Chris did his best to console Ellen, to jolly her, to make light of the situation, although it worried him that his mother and aunt would be traveling with strangers, people who were obviously of less than sterling character.

“I just wish Aunt Alex would wait a month,” said Chris. “Then I could go with you, watch out for you.”

“It isn’t our physical safety that most concerns me, Chris. These people are nothing but liars and thieves. And Alexandra wants to be young again so badly, there is no telling how much money they’ve taken from her. Don’t you see, they know how foolish she is and they may be planning to rob her of the entire fortune.”

“Now, Mother,” Chris soothed, “I’m sure you’re worrying needlessly. Aunt Alex may be behaving foolishly, but she hasn’t lost her mind. Surely she’d never let anyone get their hands on all that money.”

“I’m not so certain,” Ellen said. “I believe she’d give away the bulk of her estate if she thought it would get rid of a few wrinkles and buy her ten more years.” Her eyebrows knitted, she said, “For heaven’s sake, it is your inheritance we’re talking about here, Chris. The Landseer fortune should go to you and—”

“Mother, I wish you would stop worrying about my inheritance and—”

“Never!” Ellen said, interrupting. Her chin raised pugnaciously, she said in a cold, level voice, “I have tolerated that ill-tempered old woman all these years and I mean to see to it that you are not cheated out of what is rightfully yours.” Before he could reply, she softened and said, “It will be a long, difficult journey we’ll be making. We’re going all the way to the canyonlands of Utah. The lead guide, Mister Corey, has said that near the end we may have to walk and—”

“Corey?” Chris interrupted. “Did you say Corey? What is this Mister Corey’s full name?”

“Ah…I really don’t know. I’ve never heard anyone call him anything but Mister Corey. Why? Is the name familiar to you. Have you heard of Mister Corey?”

Chris paused with indecision, then said, “No. No, Mother, I haven’t.”

He quickly changed the subject, turning the conversation to the activities at the academy. No more was said about the journey or the man leading it.

But after Chris had seen his mother off at the train station, he hurried back to the Citadel. Its quadrangle was nearly empty on this warm spring afternoon, very few cadets on the grounds. Chris went into the silent building that housed the Hall of Honor.

In a glass display case he examined the sun-faded outline of a Silver Star, the nation’s second highest award for bravery. The medal was no longer there. Nearby, a framed photograph of the graduating class of 1882 hung on the wall. In the third row, standing fourth from the right, a cadet’s face had been crossed out.

Chris read the name below, scratched through, but still discernible.

Cadet Captain Steven J. Corey.

Eight

The contentment, the happiness, the warm glow that had enveloped Ellen during the long, lovely weekend in Charleston was rapidly slipping away. No matter how hard she tried, she was finding it difficult to retain that wonderful sense of well-being she’d felt from the minute she’d stepped off the train in Charleston on Friday afternoon.

But now it was Monday.

Blue Monday.

And the northbound train on which she rode was moving steadily closer to New York City and the terminal at Grand Central Station. The joy of the past three days was behind her, already a sweet, fading memory.

Ahead of her was a long arduous journey to the inhospitable West with her cranky aunt and a motley group of unprincipled characters led by a disrespectful man who had kissed her at the depot as if the two of them were lovers.

Ellen’s eyes opened.

A little tremor surged through her slender body. She told herself it was a shudder of revulsion at the memory of that audacious kiss.

But was it?

The train was now slowly rolling into the station. Dread was rising, creeping through her bones, tightening her throat, giving her a slight headache. Anxiously she peered out the window, praying she would not see a tall, lean man with coal-black hair and a long white scar on his right cheek waiting on the platform.

Her prayer was in vain.

Leaning lazily against a wide, square column that supported the depot roof’s overhang was Mister Corey. He was wearing a white shirt, buff-colored snug-fitting trousers and freshly polished leather shoes. Clothes that were no different from the ones worn by many of the other gentlemen on the platform. At least a half-dozen men were dressed similarly. They all looked neat, clean, harmless. Except for Mister Corey.

He looked neat.

He looked clean.

But he didn’t look harmless.

Ellen realized she was holding her breath. She didn’t want to get off the train. She didn’t want to encounter Mister Corey. She didn’t want to talk to him. She didn’t want him to drive her home. And she sure didn’t want him to kiss her.

As she made her way down the narrow aisle toward the car’s door, Ellen stiffened her spine and silently lectured herself. Never let him see that you are nervous. Insult him before he has a chance to upset you. It’s the only thing his kind understands.

Ellen stepped down from the train, tensed, expecting the dark devil to hurry forward, grab her off the steps and attempt to kiss her again. To her surprise, nothing of the kind happened. She looked about and saw that Mister Corey was still leaning against the pillar, unmoving, his arms crossed over his chest. What kind of game was he playing now?

Frowning, Ellen stepped down onto the platform, lifted her valise with effort and headed into the busy terminal. She glanced at Mister Corey out of the corner of her eye and felt her temper rise. He was making no move to come to her, to relieve her of her heavy suitcase, to assist her in any way.

Ellen went completely through the huge, crowded terminal and out onto the sidewalk in front of the station. She was raising her hand for a carriage when Mister Corey stepped up beside her, took the valise and said, “Welcome home, Ellen.”

She did not return the greeting. “Where is the carriage?”

Inclining his head, Mister Corey took her arm. “Just down the sidewalk about twenty yards. Think you can walk that far?”

“I can walk all the way home if I have to,” she warned, pointedly freeing her arm from his loose grasp.

“Then why don’t you?” he coolly challenged.

Her head snapped around and she glared at him. “Oh! I have,” she said in clipped tones, “had just about enough of you and—”

“I don’t believe you,” he cut in smoothly. His gaze briefly lowering to her lips, he said, “I don’t think, Ellen, that you’ve had nearly enough of me.”