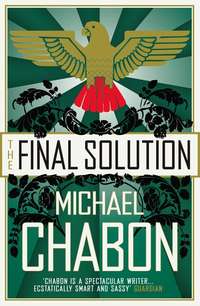

The Final Solution

‘Mother,’ he said. Then he turned and went out.

‘Mother,’ said the parrot, in his soft voice. Linus Steinman was looking at Bruno with the deep affection that was the only recognizable emotion Parkins had ever seen the boy express. And then, in a clear, fluting, tender voice Parkins had never heard, the bird began to sing.

Wien, Wien, Wien

Sterbende Märchenstadt

It was a lovely contralto and, as it issued jerkily from the bill of the grey animal in the corner, disturbingly human. They listened for a moment, and then Linus Steinman rose from his chair and went to the perch. The bird fell silent, and stepped onto the outstretched forearm that was proffered. The boy turned back to them, and his eyes were filled with tears and with a simple question as well.

‘Yes, dear,’ said Mrs Panicker with a sigh. ‘You may as well be excused.’

III

They found him sitting on the boot bench outside his front door, hatted and caped in spite of the heat, sunburnt hands clasping the head of his blackthorn stick. All ready to go. As if – though it was impossible – he were expecting them. They must have caught him on his doorstep, boots laced, gathering his strength for a late-morning tramp across the Downs.

‘Which one are you?’ he said to Inspector Bellows. His eye was exceedingly bright. The great beak quivered as if catching scent of them. ‘Speak up.’

‘Bellows,’ said the inspector. ‘Detective Inspector Michael Bellows. Sorry to bother you, sir. But I am new on the job, down here, learning the ropes, as they say, and I don’t at all overrate my capacities.’

At this last assertion the inspector’s companion, Detective Constable Quint, cleared his throat and politely directed his gaze toward the middle distance.

‘Bellows … I knew your father,’ the old man suggested. Head tottering on his feeble neck. Cheeks flecked with the blood and plaster of an old man’s hasty shave. ‘Surely? In the West End. Red-haired chap, ginger moustache. Specialized, as I recall, in confidence men. Not without ability I should have said.’

‘Sandy Bellows,’ the inspector said. ‘Grandfather, actually. And how often did I hear him speak highly of you, sir.’

Not quite so often, perhaps, the inspector thought, as I heard him curse your name.

The old man nodded, gravely. The inspector’s sharp eye detected a fleeting sadness, a flicker of memory that briefly seamed the old man’s face.

‘I have known a great many policemen,’ he said. ‘A great many.’ He brightened, wilfully. ‘But it is always a pleasure to make the acquaintance of another. And Detective Constable … Quint, I believe?’

He trained his raptor gaze now on the constable, a dark, brooding potato-nosed fellow. DC Quint was much attached, as he rarely neglected to let it be known, to the prior detective inspector, sadly deceased but a proponent apparently of the old solid methods of policework. Quint tipped a finger to the brim of his hat. Not a talkative fellow, DC Quint.

‘Now, who has died, and by what means?’ the old man said.

‘A man named Shane, sir. Struck in the back of the head with a blunt object.’

The old man looked unimpressed. Even, perhaps, disappointed.

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘Shane struck in the back of the head. Blunt object. I see.’

Perhaps a bit batty after all, thought the inspector. Not what he used to be, as Quint had put it. Pity.

‘I am not in the least senile, Inspector, I assure you,’ the old man said. He had read the trend of the inspector’s thoughts; no, that was impossible, too. Read his face, then; the cant of his shoulders. ‘But this is a crucial moment, a crisis, if you will, in the hives. I could not possibly abandon them for an unremarkable crime.’

Bellows glanced at his constable. The inspector was young enough, and murder rare enough on the South Downs, for it to seem to both policemen that there was perhaps something remarkable about a man’s skull being staved in with a poker or a sap, behind a vicarage.

‘And this Shane was armed, sir,’ DC Quint said. ‘Carried a Webley service pistol, for all that he claimed to be, and near as we can tell he were, nothing but a commercial traveller in –’ He pulled a small oilskin-covered notepad from his pocket and consulted it. The inspector had already learned to detest the sight of that notepad with its careful inventory of deeply irrelevant facts. ‘– the dairy machine and equipment line.’

‘Hit from behind,’ the inspector said. ‘It appears. In the dead of night as he was about to get into his motor. Bags all packed, apparently leaving town with no explanation or goodbye, though only just a week before he prepaid two months’ lodging at the vicarage.’

‘The vicarage, yes, I see.’ The old man closed his eyes, heavily, as if the facts in the case were not merely unremarkable but soporific. ‘And no doubt you have, quite literally unadvisedly, since you can have received no sensible counsel in the matter, leapt to the readiest conclusion, and placed young Mr Panicker under arrest for the crime.’

Though aware of the silent film comedy aspect of their behaviour, Inspector Bellows found to his shame he couldn’t prevent himself from exchanging another sheep-faced look with his constable. Reggie Panicker had been arrested at ten that morning, three hours after the discovery of the body of Richard Woolsey Shane, of Sevenoaks, Kent, in the lane behind the vicarage where the deceased had parked his 1933 MG Midget.

‘For which crime,’ continued the old man, ‘that lamentable young man in the fullness of time will duly be hanged by the neck, and his mother will weep, and then the world will continue to roll blindly on its way through the void, and in the end your Mr Shane will still be dead. But in the meantime, Inspector, Number 4 must be re-queened.’

And he waved a long-fingered starfish hand, all warts and speckles, dismissing them. Sending them along their way. He patted down the pockets of his wrinkled suit: looking for his pipe.

‘A parrot is missing!’ Inspector Michael Bellows tried, helpless, hoping this titbit might in the old man’s unimaginable estimation add some kind of lustre to the crime. ‘And we found this on the person of the vicar’s son.’

He drew from his breast pocket the dog-eared calling card of Mr Jos. Black, Dealer in Rare and Exotic Birds, Club Row, London, and submitted it to the old man, who did not give it a glance.

‘A parrot.’ Somehow, Bellows saw, he had managed not merely to impress but to astonish the old man. And the old man looked delighted to so find himself. ‘Yes, of course. An African grey. Belonging, perhaps, to a small boy. Aged about nine years. A German national – of Jewish origin, I’d wager – and incapable of speech.’

Now would have been the moment for the inspector to clear his own throat. DC Quint had argued strenuously against involving the old man in the investigation. He’s strictly non compos sir, I can heartily assure you of that. But Inspector Bellows was too flummoxed to gloat. He had heard the tales, the legends, the wild, famous leaps of induction pulled off by the old man in his heyday, assassins inferred from cigar ash, horse thieves from the absence of a watchdog’s bark. Try as he might, the inspector could not find the way to a mute German jewboy from a missing parrot and a corpse named Shane with a ventilated skull. And so he missed his opportunity to score a point off DC Quint.

Now the old man had a look at Mr Jos. Black’s calling card, lips pursed, dragging it across a range of distances from the tip of his nose until he settled on one that would do.

‘Ah,’ he said, nodding. ‘So our Mr Shane came upon young Panicker as he was making off with the poor boy’s pet, which he hoped to sell to this Mr Black. And Shane attempted to prevent him from doing so, and so paid dearly for his heroism. Do I fairly summarize your view?’

Though this was in short the whole of his theory, from the first there had been something in it – something in the circumstances of the murder itself – that troubled the inspector enough to send him, against the advice of his constable, calling on this half-legendary friend and adversary of his grandfather’s entire generation of policemen. Nevertheless it had sounded a sensible enough theory, all in all. The old man’s tone, however, rendered it as likely as the agency of fairies.

‘Ap-parently there were words between them,’ the inspector said, wincing as an ancient stammer resurfaced from the depths of his boyhood. ‘They quarrelled. It came to blows.’

‘Yes, yes. Well, I don’t doubt that you are right.’

The old man composed the seam of his mouth into the most insincere smile Inspector Bellows had ever seen.

‘And, really,’ he continued, ‘it is most fortunate that you require so little assistance from me, since, as you must know, I am retired. As indeed I have been since the tenth of August, 1914. At which time, you may take it from me, I was far less sunk in decrepitude than the withered carapace you now see before you.’ He tapped the shaft of his stick juridically against the doorstep. They were dismissed. ‘Good day.’

And then, with an echo of the love of theatrics that had so tried the patience and enlivened the language of the inspector’s grandfather, the old man tilted his face up to the sun, and closed his eyes.

The two policemen stood a moment, watching this shameless simulacrum of an afternoon nap. It crossed the inspector’s mind that perhaps the old man wished them to plead with him. He glanced at DC Quint. No doubt abject pleading with the mad old hermit was a step to which his late predecessor would never have been reduced. And yet how much there was to be learned from such a man if only one could—

The eyes snapped open, and now the smile hardened into something more sincere and cruel.

‘Still here?’ he said.

‘Sir – if I may—’

‘Very well.’ The old man chuckled dryly, entirely to himself. ‘I have considered the needs of my bees. And I believe that I can spare a few hours. Therefore I will assist you.’ He held up a long, admonishing finger. ‘To find the boy’s parrot.’ Laboriously, and with an air that rebuffed in advance any offers of assistance, the old man, relying heavily on his scarred black stick, hoisted himself onto his feet. ‘If we should encounter the actual murderer along the way, well, then it will be so much the better for you.’

IV

The old man settled himself onto one knee. The left one; the right knee was no good for anything anymore. It took him a damnably long time, and on the way down there was a horrible snapping sound. But he managed it and went about his work with dispatch. He pulled off his right glove and poked his naked finger into the bloody mud where Richard Woolsey Shane’s life had seeped away. Then he reached into the old conjuror’s pocket sewn into the lining of his cloak and took out his glass. It was brass and tortoise shell, and bore around its bezel an affectionate inscription from the sole great friend of his life.

With a series of huffings and grunts, labouring across twenty feet square of level ground as if they were the sheer icy face of Karakorum, the old man turned his beloved lens upon everything that occupied or surrounded the fatal spot, tucked between the lush green hedgerows of Hallows Lane, at which Shane’s half-headless body had been found, early that morning, by his landlord, Mr Panicker. Alas that the body had already been moved, and by clumsy men in heavy boots! All that remained was its faint imprint, a twisted cross in the dust. On the right tyre of the dead man’s motorcar – awfully flash for a traveller in milking machines – he noted the centripetal pattern and moderate degree of darkening in the feathery spray of blood on the tyre’s white wall. Though the police had made a search of the car, turning up an Ordnance Survey map of Sussex, a length of clear rubber milking hose, bits of valve and pipe, several glossy prospectuses for the Chedbourne & Jones Lactrola R-5, and a well-thumbed copy of Treadley’s Common Diseases of Milch Kine, 1926 edition, the old man went over the whole thing again. All the while, though he was unaware of it, he kept up a steady muttering, nodding his head from time to time, carrying on one half of a conversation, and showing a certain impatience with his invisible interlocutor. This procedure required nearly forty minutes, but when he emerged from the car, feeling quite as if he ought to lie down, he was holding a live .45 calibre cartridge for that highly unlikely Webley, and an unsmoked Murat cigarette, an Egyptian brand whose choice by the victim, were it his, seemed to indicate still greater unsuspected depths of experience or romance. Finally he dug around in the mulchy earth that lay beneath the hedgerows, finding in the process a piece of shattered cranium, stuck with bits of skin and hair, that the policemen, to their evident discomfiture, had missed.

He handled the grisly bit of evidence without hesitation or qualm. He had seen human beings in every state, phase and attitude of death: a Cheapside drab tumbled, throat cut, headfirst down a stairway of the Thames Embankment, blood pooling in her mouth and eye sockets; a stolen child, green as a kelpie, stuffed into a storm drain; the papery pale husk of a pensioner, killed with arsenic over the course of a dozen years; a skeleton looted by kites and dogs and countless insects, bleached and creaking in a wood, tattered garments fluttering like flags; a pocketful of teeth and bone chips in a shovelful of pale incriminating ash. There was nothing remarkable, nothing at all, about the crooked X that death had scrawled in the dust of Hallows Lane.

At last he put the glass away and stood up as straight as he could manage. He gave a last look around at the situation of the hedgerows, the MG under its tarpaulin of dust, the behaviour of the rooks, the direction taken by the coal smoke streaming from the chimney of the vicarage. Then he turned to the young inspector, studying him at some length without speaking.

‘Anything wrong?’ Sandy Bellows’s grandson said. So far the old man had refrained from asking the inspector whether his grandfather was living or dead. He knew all too well what the answer would be.

‘You have done a fine job,’ the old man said. ‘First rate.’

The inspector smiled, and his eyes travelled to the sullen Constable Quint, standing by the little green roadster. The constable pulled on one half of his moustache and glowered at the muddy purple puddle at his feet.

‘Shane was approached and struck, with considerable force, from behind; you have that much right. Tell me, Inspector, how you square that with your idea that the deceased came upon and surprised young Mr Panicker in the act of stealing the parrot?’

Bellows started to speak, then left off with a short, weary sigh, and shook his head. DC Quint tugged his moustache down now, in an attempt to conceal the smile that had formed on his lips.

‘The pattern and frequency of footprints indicates,’ the old man continued, ‘that at the moment the blow fell Mr Shane was moving in some haste, and carrying something in his left hand, something rather heavy, I should wager. Since your men found his valise and all of his personal effects by the garden door, as if waiting to be transferred to the boot of the car, and since the birdcage is nowhere to be found, I think it reasonable to infer that Shane was fleeing, when he was murdered, with the birdcage. Presumably the bird was in it, though I think a thorough search of neighbourhood trees ought to be made, and soon.’

The young inspector turned to DC Quint and nodded once. DC Quint let go of his moustache. He looked aghast.

‘You can’t mean, sir, with all due respect, that you want me to waste valuable time staring up into trees looking for a—’

‘Oh, you needn’t worry, Detective Constable,’ the old man said, with a wink. He did not care to divulge his hypothesis – naturally only one of several under consideration – that Bruno the African grey parrot might be clever enough to have engineered an escape from his captor. Men, policemen in particular, tended to discount the capacity of animals to enact, often with considerable panache, the foulest of crimes and the most daring stunts. ‘You can’t miss the tail.’

Constable Quint seemed unable for a moment to gain control of the musculature of his jaw. Then he turned and stomped off down the lane, toward the trellised doorway that led into the garden of the vicarage.

‘As for you.’ The old man turned to the inspector. ‘You must seek to inform yourself about our victim. I will want to see the body, of course. I suspect we may discover—’

A woman screamed, grandly at first, almost one would have said with a hint of melody. Then her cry disintegrated into a series of little gasping barks:

Oh oh oh oh oh –

The inspector took off at a run, leaving the old man to follow scraping and hobbling along behind. When he came into the garden he saw a number of familiar objects and entities set about on an expanse of green as if arranged to a desired effect or inferable purpose, like counters or chessmen in some kingly recreation. Regarding them the old man experienced a moment of vertiginous horror during which he could neither reckon their number nor recall their names or purposes. He felt – with all his body, as one felt the force of gravity or inertia – the inevitability of his failure. The conquest of his mind by age was not a mere blunting or slowing down but an erasure, as of a desert capital by a drifting millennium of sand. Time had bleached away the ornate pattern of his intellect, leaving a blank white scrap. He feared then that he was going to be sick, and raised the head of his stick to his mouth. It was cold against his lips. The horror seemed to subside at once; consciousness rallied itself around the brutal taste of metal, and all at once he found himself looking, with inexpressible relief, merely at the two policemen, Bellows and Quint; at Mr and Mrs Panicker, standing on either side of a bird bath; at a handsome Jew in a grey suit; a sundial; a wooden chair; a hawthorn bush in lavish flower. They were all gazing upward to the peak of the vicarage’s thatched roof at the remaining token in the game.

‘Young man, you will come down from there at once!’

The voice was that of Mr Panicker – who was rather more intelligent than the average country parson, in the old man’s view, and rather less competent to minister to the souls of his parishioners. He backed a step or two away from the house as if to find a better spot from which to fix the boy on the roof of the house with a baleful stare. But the vicar’s eyes were far too large and sorrowful, the old man thought, ever to do the trick.

‘Sonny boy,’ Constable Quint called up. ‘You’re going to break your neck!’

The boy stood, upright, hands dangling by his sides, feet together, teetering on the fulcrum of his heels. He looked neither distressed nor playful, merely gazed down at his shoes or at the ground far below him. The old man wondered if he could have gone up there to search for his parrot. Perhaps in the past the bird had been known to take refuge on housetops.

‘Fetch a ladder,’ the inspector said.

The boy slipped, and went sliding on his bottom down the long thatch slope of the roof toward the edge. Mrs Panicker let out another scream. At the last moment the boy gripped two fistfuls of thatch and held on to them. His progress was arrested with a jerk, and then the handfuls ripped free of the roof and he sailed out into the void and plummeted to earth, landing on top of the good-looking young Jewish man, a Londoner by the cut of his suit, with a startling crunch like a barrel shattering against rocks. After a dazed moment the boy stood up, and shook his hands as if they stung him. Then he offered one to the man on his belly on the ground.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов