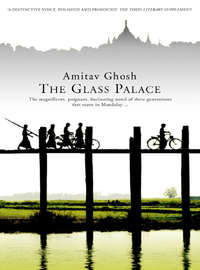

The Glass Palace

‘Yes. I was sick, but I lived. In my family I was the only one. I had a father, a sister, brothers …’

‘And a mother?’

‘And a mother.’

Rajkumar’s mother had died on a sampan that was tethered in a mangrove-lined estuary. He remembered the tunnel-like shape of the boat’s galley and its roof of hooped cane and thatch; there was an oil lamp beside his mother’s head, on one of the crosswise planks of the hull. Its flickering yellow flame was dulled by a halo of night-time insects. The night was still and airless, with the mangroves and their dripping roots standing thick against the breeze, cradling the boat between deep banks of mud. Yet there was a kind of restlessness in the moist darkness around the boat. Every now and again, he’d hear the splash of seed pods arrowing into the water, and the slippery sound of fish, stirring in the mud. It was hot in the sampan’s burrow-like galley, but his mother was shivering. Rajkumar had scoured the boat, covering her with every piece of cloth that he could find.

Rajkumar knew the fever well by that time. It had come to their house through his father, who worked every day at a warehouse, near the port. He was a quiet man, who made his living as a dubash and a munshi – a translator and clerk – working for a succession of merchants along the eastern shore of the Bay of Bengal. Their family home was in the port of Chittagong, but his father had quarrelled with their relatives and moved the family away, drifting slowly down the coast, peddling his knowledge of figures and languages, settling eventually in Akyab, the principal port of the Arakan – that tidewater stretch of coast where Burma and Bengal collide in a whirlpool of unease. There he’d remained for some dozen years, fathering three children – of these the oldest was Rajkumar. Their home was on an inlet that smelt of drying fish. Their family name was Raha, and when their neighbours asked who they were and where they came from they would say they were Hindus from Chittagong. That was all Rajkumar knew about his family’s past.

Rajkumar was the next to fall sick, after his father. He had returned to consciousness to find himself recovering at sea, with his mother. They were on their way back to their native Chittagong, she told him, and there were just the two of them now – the others were gone.

The sailing had been slow because the currents were against them. The square-sailed sampan and her crew of khalasis had fought their way up the coast, hugging the shore. Rajkumar had recovered quickly, but then it was his mother’s turn to sicken. With Chittagong just a couple of days away she had begun to shiver. The shore was thick with mangrove forests; one evening, the boatowner had pulled the sampan into a creek and settled down to wait.

Rajkumar had covered his mother with all the saris in her cloth bundle, with longyis borrowed from the boatmen, even a folded sail. But he’d no sooner finished than her teeth began to chatter again, softly, like dice. She called him to her side, beckoning with a forefinger. When he lowered his ear to her lips, he could feel her body glowing like hot charcoal against his cheek.

She showed him a knot on the tail end of her sari. There was a gold bangle wrapped in it. She pulled it out and gave it to him to hide in the waist knot of his sarong. The nakhoda, the boat’s owner, was a trustworthy old man, she told him; Rajkumar was to give him the bangle when they reached Chittagong – only then, not before.

She folded his fingers around the bangle: warmed by the fiery heat of her body, the metal seemed to singe its shape into his palm. ‘Stay alive,’ she whispered. ‘Beche thako, Rajkumar. Live, my Prince; hold on to your life.’

When her voice faded away Rajkumar became suddenly aware of the faint flip-flop sound of catfish burrowing in the mud. He looked up to see the boatowner, the nakhoda, squatting in the prow of the sampan, puffing on his coconut-shell hookah, fingering his thin, white beard. His crewmen were sitting clustered round him, watching Rajkumar. They were hugging their sarong-draped knees. The boy could not tell whether it was pity or impatience that lay behind the blankness in their eyes.

He had only the bangle now: his mother had wanted him to use it to pay for his passage back to Chittagong. But his mother was dead and what purpose would it serve to go back to a place that his father had abandoned? No, better instead to strike a bargain with the nakhoda. Rajkumar took the old man aside and asked to join the crew, offering the bangle as a gift of apprenticeship.

The old man looked him over. The boy was strong and willing, and, what was more, he had survived the killer fever that had emptied so many of the towns and villages of the coast. That alone spoke of certain useful qualities of body and spirit. He gave the boy a nod and took the bangle – yes, stay.

At daybreak the sampan stopped at a sand bar and the crew helped Rajkumar build a pyre for his mother’s cremation. Rajkumar’s hands began to shake when he put the fire in her mouth. He, who had been so rich in family, was alone now, with a khalasi’s apprenticeship for his inheritance. But he was not afraid, not for a moment. His was the sadness of regret – that they had left him so soon, so early, without tasting the wealth or the rewards that he knew, with utter certainty, would one day be his.

It was a long time since Rajkumar had spoken about his family. Among his shipmates this was a subject that was rarely discussed. There were many among them who were from families that had fallen victim to the catastrophes that were so often visited upon that stretch of coast. They preferred not to speak of these things.

It was odd that this child, Matthew, with his educated speech and formal manners, should have drawn him out. Rajkumar could not help being touched. On the way back to Ma Cho’s, he put an arm round the boy’s shoulders. ‘So how long are you going to be here?’

‘I’m leaving tomorrow.’

‘Tomorrow? But you’ve just arrived.’

‘I know. I was meant to stay for two weeks, but Father thinks there’s going to be trouble.’

‘Trouble!’ Rajkumar turned to stare at him. ‘What trouble?’

‘The English are preparing to send a fleet up the Irrawaddy. There’s going to be a war. Father says they want all the teak in Burma. The King won’t let them have it so they’re going to do away with him.’

Rajkumar gave a shout of laughter. ‘A war over wood? Who’s ever heard of such a thing?’ He gave Matthew’s head a disbelieving pat: the boy was a child, after all, despite his grown-up ways and his knowledge of unlikely things; he’d probably had a bad dream the night before.

But this proved to be the first of many occasions when Matthew showed himself to be wiser and more prescient than Rajkumar. Two days later the whole city was gripped by rumours of war. A large detachment of troops came marching out of the fort and went off downriver, towards the encampment of Myingan. There was an uproar in the bazaar; fishwives emptied their wares into the refuse heap and went hurrying home. A dishevelled Saya John came running to Ma Cho’s stall. He had a sheet of paper in his hands. ‘A Royal Proclamation,’ he announced, ‘issued under the King’s signature.’

Everybody in the stall fell silent as he began to read:

To all Royal subjects and inhabitants of the Royal Empire: those heretics, the barbarian English kalaas having most harshly made demands calculated to bring about the impairment and destruction of our religion, the violation of our national traditions and customs, and the degradation of our race, are making a show and preparation as if about to wage war with our state. They have been replied to in conformity with the usages of great nations and in words which are just and regular. If, notwithstanding, these heretic foreigners should come, and in any way attempt to molest or disturb the state, His Majesty, who is watchful that the interest of our religion and our state shall not suffer, will himself march forth with his generals, captains and lieutenants with large forces of infantry, artillery, elephanterie and cavalry, by land and by water, and with the might of his army will efface these heretics and conquer and annex their country. To uphold the religion, to uphold the national honour, to uphold the country’s interests will bring about threefold good – good of our religion, good of our master and good of ourselves and will gain for us the important result of placing us on the path to the celestial regions and to Nirvana.

Saya John pulled a face. ‘Brave words,’ he said. ‘Let’s see what happens next.’

After the initial panic, the streets quickly quietened. The bazaar reopened and the fishwives came back to rummage through the refuse heap, looking for their lost goods. Over the next few days people went about their business just as they had before. The one most noticeable change was that foreign faces were no longer to be seen on the streets. The number of foreigners living in Mandalay was not insubstantial – there were envoys and missionaries from Europe; traders and merchants of Greek, Armenian, Chinese and Indian origin; labourers and boatmen from Bengal, Malaya and the Coromandel coast; white-clothed astrologers from Manipur; businessmen from Gujarat – an assortment of people such as Rajkumar had never seen before he came here. But now suddenly the foreigners disappeared. It was rumoured that the Europeans had left and gone downriver while the others had barricaded themselves into their houses.

A few days later the palace issued another proclamation, a joyful one, this time: it was announced that the royal troops had dealt the invaders a signal defeat, near the fortress of Minhla. The English troops had been repulsed and sent fleeing across the border. The royal barge was to be dispatched downriver, bearing decorations for the troops and their officers. There was to be a ceremony of thanksgiving at the palace.

There were shouts of joy on the streets, and the fog of anxiety that had hung over the city for the last few days dissipated quickly. To everyone’s relief things went quickly back to normal: shoppers and shopkeepers came crowding back and Ma Cho’s stall was busier than ever before.

Then, one evening, racing into the bazaar to replenish Ma Cho’s stock of fish, Rajkumar came across the familiar, white-bearded face of his boatowner, the nakhoda.

‘Is our boat going to leave soon now?’ Rajkumar asked. ‘Now that the war is over?’

The old man gave him a secret, tight-lipped smile. ‘The war isn’t over. Not yet.’

‘But we heard …’

‘What we hear on the waterfront is quite different from what’s said in the city.’

‘What have you heard?’ said Rajkumar.

Although they were using their own dialect the nakhoda lowered his voice. ‘The English are going to be here in a day or two,’ he answered. ‘They’ve been seen by boatmen. They are bringing the biggest fleet that’s ever sailed on a river. They have cannon that can blow away the stone walls of a fort; they have boats so fast that they can outrun a tidal bore; their guns can shoot quicker than you can talk. They are coming like the tide: nothing can stand in their way. Today we heard that their ships are taking up positions around Myingan. You’ll probably hear the fireworks tomorrow …’

Sure enough, the next morning, a distant booming sound came rolling across the plain, all the way to Ma Cho’s food-stall, near the western wall of the fort. When the opening salvoes sounded, the market was thronged with people. Farm wives from the outskirts of the city had come in early and set their mats out in rows, arranging their vegetables in neat little bunches. Fishermen had stopped by too, with their night-time catches fresh from the river. In an hour or two the vegetables would wilt and the fish eyes would begin to cloud over. But for the moment everything was crisp and fresh.

The first booms of the guns caused nothing more than a brief interruption in the morning’s shopping. People looked up at the clear blue sky in puzzlement and shopkeepers leant sidewise over their wares to ask each other questions. Ma Cho and Rajkumar had been hard at work since dawn. As always on chilly mornings, many people had stopped off for a little something to eat before making their way home. Now the hungry, mealtime hush was interrupted by a sudden buzz. People looked at each other nervously: what was that noise?

This was when Rajkumar broke in. ‘English cannon,’ he said. ‘They’re heading in this direction.’

Ma Cho gave a yelp of annoyance. ‘How do you know what they are, you fool of a boy?’

‘Boatmen have seen them,’ Rajkumar answered. ‘A whole English fleet is coming this way.’

Ma Cho had a roomful of people to feed and she was in no mood to allow her only helper to be distracted by a distant noise.

‘Enough of that now,’ she said. ‘Get back to work.’

In the distance the firing intensified, rattling the bowls on the benches. The customers began to stir in alarm. In the adjoining marketplace a coolie had dropped a sack of rice and the spilt grain was spreading like a white stain across the dusty path as people pushed past each other to get away. Shopkeepers were clearing their counters, stuffing their goods into bags; farm wives were tipping their baskets into refuse heaps.

Suddenly Ma Cho’s customers started to their feet, knocking over their bowls and pushing the benches apart. In dismay, Ma Cho turned on Rajkumar. ‘Didn’t I tell you to keep quiet, you idiot of a kalaa? Look, you’ve scared my customers away.’

‘It’s not my fault …’

‘Then whose? What am I going to do with all this food? What’s going to become of that fish I bought yesterday?’ Ma Cho collapsed on her stool.

Behind them, in the now-deserted marketplace, dogs were fighting over scraps of discarded meat, circling in packs around the refuse heaps.

Two

At the palace, a little less than a mile from Ma Cho’s stall, the King’s chief consort, Queen Supayalat, was seen mounting a steep flight of stairs to listen more closely to the guns.

The palace lay at the exact centre of Mandalay, deep within the walled city, a sprawling complex of pavilions, gardens and corridors, all grouped around the nine-roofed hti of Burma’s kings. The complex was walled off from the surrounding streets by a stockade of tall, teak posts. At each of the four corners of the stockade was a guard-post, manned by sentries from the King’s personal bodyguard. It was to one of these that Queen Supayalat had decided to climb.

The Queen was a small, fine-boned woman with porcelain skin and tiny hands and feet. Her face was small and angular, the regularity of its features being marred only by a slight blemish in the alignment of the right eye. The Queen’s waist, famously of a wisp-like slimness, was swollen by her third pregnancy, now in its eighth month.

The Queen was not alone: some half-dozen maidservants followed close behind, carrying her two young daughters, the First and Second Princesses, Ashin Hteik Su Myat Phaya Gyi and Ashin Hteik Su Myat Phaya Lat. The advanced condition of her pregnancy had made the Queen anxious about her children’s whereabouts. For the last several days she had been unwilling to allow her two daughters even momentarily out of her sight.

The First Princess was three and bore a striking resemblance to her father, Thebaw, King of Burma. She was a good-natured, obedient girl, with a round face and ready smile. The Second Princess was two years younger, not quite one yet, and she was an altogether different kind of child, very much her mother’s daughter. She’d been born with the colic and would cry for hours at a stretch. Several times a day she would fly into paroxysms of rage. Her body would go rigid and she would clench her little fists; her chest would start pumping, with her mouth wide open but not a sound issuing from her throat. Even experienced nurses quailed when the little Princess was seized by one of her fits.

To deal with the baby, the Queen insisted on having several of her most trusted attendants at hand at all times – Evelyn, Hemau, Augusta, Nan Pau. These girls were very young, mostly in their early teens, and they were almost all orphans. They’d been purchased by the Queen’s agents in small Kachin, Wa and Shan villages along the kingdom’s northern frontiers. Some of them were from Christian families, some from Buddhist – once they came to Mandalay it didn’t matter. They were reared under the tutelage of palace retainers, under the Queen’s personal supervision.

It was the youngest of these maids who had had the most success in dealing with the Second Princess. She was a slender ten-year-old called Dolly, a timid, undemonstrative child, with enormous eyes and a dancer’s pliable body and supple limbs. Dolly had been brought to Mandalay at a very early age from the frontier town of Lashio: she had no memory of her parents or family. She was thought to be of Shan extraction, but this was a matter of conjecture, based on her slender fine-boned appearance and her smooth, silken complexion.

On this particular morning Dolly had had very little success with the Second Princess. The guns had jolted the little girl out of her sleep and she had been crying ever since. Dolly, who was easily startled, had been badly scared herself. When the guns had started up she’d covered her ears and gone into a corner, gritting her teeth and shaking her head. But then the Queen had sent for her and after that Dolly had been so busy trying to distract the little Princess that she’d had no time to be frightened.

Dolly wasn’t strong enough yet to take the Princess up the steep stairs that led to the top of the stockade: Evelyn, who was sixteen and strong for her age, was given the job of carrying her. Dolly followed after the others and she was the last to step into the guard-post – a wooden platform, fenced in with heavy, timber rails.

Four uniformed soldiers were standing grouped in a corner. The Queen was firing questions at them, but none of them would answer nor even meet her eyes. They hung their heads, fingering the long barrels of their flintlocks.

‘How far away is the fighting?’ the Queen asked. ‘And what sort of cannon are they using?’

The soldiers shook their heads; the truth was that they knew no more than she did. When the noise started they’d speculated excitedly about its cause. At first they’d refused to believe that the roar could be of human making. Guns of such power had never before been heard in this part of Burma, nor was it easy to conceive of an order of fire so rapid as to produce an indistinguishable merging of sound.

The Queen saw that there was nothing to be learnt from these hapless men. She turned to rest her weight against the wooden rails of the guard-post. If only her body were less heavy, if only she were not so tired and slow.

The strange thing was that these last ten days, ever since the English crossed the border, she’d heard nothing but good news. A week ago a garrison commander had sent a telegram to say that the foreigners had been stopped at Minhla, two hundred miles downriver. The palace had celebrated the victory, and the King had even sent the general a decoration. How was it possible that the invaders were now close enough to make their guns heard in the capital?

Things had happened so quickly: a few months ago there’d been a dispute with a British timber company – a technical matter concerning some logs of teak. It was clear that the company was in the wrong; they were side-stepping the kingdom’s customs regulations, cutting up logs to avoid paying duties. The royal customs officers had slapped a fine on the company, demanding arrears of payment for some fifty thousand logs. The Englishmen had protested and refused to pay; they’d carried their complaints to the British Governor in Rangoon. Humiliating ultimatums had followed. One of the King’s senior ministers, the Kinwun Mingyi, had suggested discreetly that it might be best to accept the terms; that the British might allow the Royal Family to remain in the palace in Mandalay, on terms similar to those of the Indian princes – like farmyard pigs in other words, to be fed and fattened by their masters; swine, housed in sties that had been tricked out with a few little bits of finery.

The Kings of Burma were not princes, the Queen had told the Kinwun Mingyi; they were kings, sovereigns, they’d defeated the Emperor of China, conquered Thailand, Assam, Manipur. And she herself, Supayalat, she had risked everything to secure the throne for Thebaw, her husband and step-brother. Was it even imaginable that she would consent to give it all away now? And what if the child in her belly were a boy (and this time she was sure it was): how would she explain to him that she had surrendered his patrimony because of a quarrel over some logs of wood? The Queen had prevailed and the Burmese court had refused to yield to the British ultimatum.

Now, gripping the guard-post rail the Queen listened carefully to the distant gunfire. She’d hoped at first that the barrage was an exercise of some kind. The most reliable general in the army, the Hlethin Atwinwun, was stationed at the fort of Myingan, thirty miles away, with a force of eight thousand soldiers.

Just yesterday the King had asked, in passing, how things were going on the war front. She could tell that he thought of the war as a faraway matter, a distant campaign, like the expeditions that had been sent into the Shan highlands in years past, to deal with bandits and dacoits.

Everything was going as it should, she’d told him; there was nothing to worry about. And so far as she knew, this was no less than the truth. She’d met with the seniormost officials every day, the Kinwun Mingyi, the Taingda Mingyi, even the wungyis and wundauks and myowuns. None of them had so much as hinted that anything was amiss. But there was no mistaking the sound of those guns. What was she going to tell the King now?

The courtyard beneath the stockade filled suddenly with voices.

Dolly stole a glance down the staircase. There were soldiers milling around below, dozens of them, wearing the colours of the palace guard. One of them spotted her and began to shout – the Queen? Is the Queen up there?

Dolly stepped quickly back, out of his line of sight. Who were these soldiers? What did they want? She could hear their feet on the stairs now. Somewhere close by, the Princess began to cry, in short, breathless gasps. Augusta thrust the baby into her arms – here, Dolly, here, take her, she won’t stop. The baby was screaming, flailing her fists. Dolly had to turn her face away to keep from being struck.

An officer had stepped into the guard-post; he was holding his sheathed sword in front of him, in both hands, like a sceptre. He was saying something to the Queen, motioning to her to leave the cabin, to go down the stairs into the palace.

‘Are we prisoners then?’ The Queen’s face was twisted with fury. ‘Who has sent you here?’

‘Our orders came from the Taingda Mingyi,’ the officer said. ‘For your safety Mebya.’

‘Our safety?’

The guard-post was full of soldiers and they were herding the girls towards the steps. Dolly glanced down: the flight of stairs was very steep. Her head began to spin.

‘I can’t,’ she cried. ‘I can’t.’ She would fall, she knew it. The Princess was too heavy for her; the stairs were too high; she would need a free hand to hold on, to keep her balance.

‘Move.’

‘I can’t.’ She could hardly hear herself over the child’s cries. She stood still, refusing to budge.

‘Quickly, quickly.’ There was a soldier behind her; he was prodding her with the cold hilt of his sword. She felt her eyes brimming over, tears flooding down her face. Couldn’t they see she would fall, that the Princess would tumble out of her grip? Why would no one help?

‘Quick.’

She turned to look into the soldier’s unsmiling face. ‘I can’t. I have the Princess in my arms and she’s too heavy for me. Can’t you see?’ No one seemed to be able to hear her above the Princess’s wails.

‘What’s the matter with you, girl? Why’re you standing there? Move.’