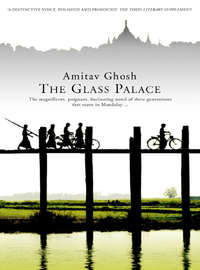

The Glass Palace

Many thousands kept vigil through the night. The steamer’s name was Thooriya, the sun. At daybreak, when the skies lightened over the hills, it was gone.

Five

After five days on the Irrawaddy the Thooriya slipped into the Rangoon river in the near-darkness of late evening. It anchored at mid-river, a good distance from the city’s busy dockside.

At first light the next day the King went up on deck, carrying a pair of gilded binoculars. The glasses were of French manufacture, a prized heirloom that had once belonged to King Mindon. The old King had been much attached to the binoculars and had always carried them with him, even into his Audience Hall.

It was a cold morning and an opaque fog had risen off the river. The King waited patiently for the sun to scorch away the mist. When it had thinned a little he raised his glasses. Suddenly, there it was, the sight he had longed to see all his life: the towering mass of the Shwe Dagon pagoda, larger even than he had imagined, its hti thrusting skywards, floating on a bed of mist and fog, shining in the light of the dawn. He had worked on the hti himself, helped with his own hands in the gilding of the spire, layering sheets of gold leaf upon each other. It was King Mindon who had had the hti cast, in Mandalay; it had been sent down to the Shwe Dagon in a royal barge. He, Thebaw, had been a novice in the monastery then, and everybody, even the seniormost monks, had vied with each other for the honour of working on the hti.

The King lowered his binoculars to scan the city’s waterfront. The instrument’s rims welled over with a busy mass of things: walls, columns, carriages and hurrying people. Thebaw had heard about Rangoon from his half-brother, the Thonzai Prince. The town was founded by their ancestor, Alaungpaya, but few members of their dynasty had ever been able to visit it. The British had seized the town before Thebaw’s birth, along with all of Burma’s coastal provinces. It was then that the frontiers of the Burmese kingdom were driven back, almost halfway up the Irrawaddy. Since then the only members of the Royal Family who had been able to visit Rangoon were rebels and exiles, princes who had fallen out with the ruling powers in Mandalay.

The Thonzai Prince was one such: he had quarrelled with old King Mindon and had fled downriver, taking refuge in the British-held city. Later the Prince had been forgiven and had returned to Mandalay. In the palace he was besieged with questions: everyone wanted to know about Rangoon. Thebaw was in his teens then and he had listened spellbound as the Prince described the ships that were to be seen on the Rangoon river: the Chinese junks and Arab dhows and Chittagong sampans and American clippers and British ships-of-the-line. He had heard about the Strand and its great pillared mansions and buildings, its banks and hotels; about Godwin’s wharf and the warehouses and timber mills that lined Pazundaung Creek; the wide streets and the milling crowds and the foreigners who thronged the public places: Englishmen, Cooringhees, Tamils, Americans, Malays, Bengalis, Chinese.

One of the stories the Thonzai Prince used to tell was about Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor. After the suppression of the uprising of 1857 the British had exiled the deposed emperor to Rangoon. He’d lived in a small house not far from the Shwe Dagon. One night the Prince had slipped off with a few of his friends and gone to look at the emperor’s house. They’d found him sitting on his veranda, fingering his beads. He was blind and very old. The Prince and his friends had meant to approach him but at the last minute they had changed their minds. What could you say to such a man?

There was a street in Rangoon, the Prince had said, that was named after the old emperor – Mughal Street. Many Indians lived there: the Prince had claimed that there were more Indians than Burmese in Rangoon. The British had brought them there, to work in the docks and mills, to pull rickshaws and empty the latrines. Apparently they couldn’t find local people to do these jobs. And indeed, why would the Burmese do that kind of work? In Burma no one ever starved, everyone knew how to read and write, and land was to be had for the asking: why should they pull rickshaws and carry nightsoil?

The King raised his glasses to his eyes and spotted several Indian faces, along the waterfront. What vast, what incomprehensible power, to move people in such huge numbers from one place to another – emperors, kings, farmers, dockworkers, soldiers, coolies, policemen. Why? Why this furious movement – people taken from one place to another, to pull rickshaws, to sit blind in exile?

And where would his own people go, now that they were a part of this empire? It wouldn’t suit them, all this moving about. They were not a portable people, the Burmese; he knew this, very well, for himself. He had never wanted to go anywhere. Yet here he was, on his way to India.

He turned to go below deck again: he didn’t like to be away from his cabin too long. Several of his valuables had disappeared, some of them on that very first day, when the English officers were transporting them from the palace to the Thooriya. He had asked about the lost things and the officers had stiffened and looked offended and talked of setting up a committee of inquiry. He had realised that for all their haughty ways and grand uniforms, they were not above some common thievery.

The strange thing was that if only they’d asked he’d gladly have gifted them some of his baubles; they would probably have received better things than those they’d taken – after all, what did they know about gemstones?

Even his ruby ring was gone. The other things he didn’t mind so much – they were just trinkets – but he grieved for the Ngamauk. They should have left him the Ngamauk.

On arriving in Madras, King Thebaw and his entourage were taken to the mansion that had been made over to them for the duration of their stay in the city. The house was large and luxurious but there was something disconcerting about it. Perhaps it was the contingent of fierce-looking British soldiers standing at the gate or perhaps it had something to do with the crowds of curious onlookers who gathered round its walls every day. Whatever it was, none of the girls felt at home there.

Mr Cox often urged the members of the household to step outside, to walk in the spacious, well-kept gardens (Mr Cox was an English policeman who had accompanied them on their journey from Rangoon and he spoke Burmese well). Dolly, Evelyn and Augusta dutifully walked around the house a few times but they were always glad to be back indoors.

Strange things began to happen. There was news from Mandalay that the royal elephant had died. The elephant was white, and so greatly cherished that it was suckled on breast-milk: nursing mothers would stand before it and slip off their blouses. Everyone had known that the elephant would not long survive the fall of the dynasty. But who could have thought that it would die so soon? It seemed like a portent. The house was sunk in gloom.

Unaccountably, the King developed a craving for pork. Soon he was consuming inordinate amounts of bacon and ham. One day he ate too much and fell sick. A doctor arrived with a leather bag and went stomping through the house in his boots. The girls had to follow behind him, swabbing the floor. No one slept that night.

One morning Apodaw Mahta, the elderly woman who supervised the Queen’s nurses, ran outside and climbed into a tree. The Queen sent the other nurses to persuade her to climb down. They spent an hour under the tree. Apodaw Mahta paid no attention.

The Queen called the nurses back and sent Dolly and the other girls to talk to Apodaw Mahta. The tree was a neem and its foliage was very dense. The girls stood round the trunk and looked up. Apodaw Mahta had wedged herself into a fork between two branches.

‘Come down,’ said the girls. ‘It’s going to be dark soon.’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’

‘I was a squirrel in my last birth. I remember this tree. This is where I want to stay.’

Apodaw Mahta had a pot belly and warts on her face. ‘She looks more like a toad than a squirrel,’ Evelyn whispered. The girls screamed with laughter and ran back inside.

U Maung Gyi, the interpreter, went out and shook his fist at her. The King was going to come down from his room, he said, and he was going to bring a stick to beat her with. At that Apodaw Mahta came scurrying down. She’d lived in the Mandalay palace for a very long time and was terrified of the King.

Anyone could have told her that the last thing in the world the King was likely to do was to run out into the garden and beat her with a stick. He’d never once stepped out of the house in all the time they’d been in Madras. Towards the beginning of their stay he had once asked to visit the Madras Museum. This had taken Mr Cox by surprise and he had said no, quite vehemently. After that, as though in protest, the King had refused to step out of the house.

Sitting in his room, with nothing to do, curious fancies began to enter the King’s mind. He decided to have a huge gold plate made in preparation for the birth of his new child. The plate would weigh several pounds and it would be set with one hundred and fifty of his most valuable rubies. To pay for the plate, he began to sell some of his possessions. The household’s Tamil employees served as his emissaries.

Some of these employees were spies and Mr Cox soon found out about the sales. He was furious. The King was wasting his wealth, he said, and what was more, he was being cheated. The servants were selling his things for a fraction of their value.

This made the King even more secretive in his dealings. He handed Dolly and Evelyn expensive jewellery and asked them to arrange to have it sold. The result was that he got even lower prices. Inevitably the Englishmen found out through their spies. They declared that the King couldn’t be trusted with money and enacted a law appropriating his family’s most valuable properties.

A mutinous quiet descended on the mansion. Dolly began to notice odd little changes in Evelyn and Augusta and her other friends. Their shikoes became perfunctory; they began to complain about sore knees and refused to stay on all fours while waiting on the Queen. Sometimes when she shouted at them they would scowl back at her.

One night the Queen woke up thirsty and found all her maids asleep beside her bed. She was so angry she threw a lamp at the wall and slapped Evelyn and Mary.

Evelyn was very upset. She said to Dolly: ‘They can’t hit us and beat us any more. We don’t have to stay if we don’t want to.’

‘How do you know?’ Dolly said.

‘Mr Cox told me. He said we were slaves in Mandalay but now we’re free.’

‘But we’re prisoners, aren’t we?’

‘Not us,’ said Evelyn. ‘Only Min and Mebya’ – meaning the King and Queen.

Dolly thought about this for a while. ‘And what about the Princesses?’

Now it was Evelyn’s turn to think.

‘Yes,’ she said at last. ‘The Princesses are prisoners too.’

That settled the matter as far as Dolly was concerned. Where the Princesses were, she would be too: she couldn’t imagine what they would do without her.

One morning a man arrived at the gate saying he’d come from Burma to take his wife back home. His wife was Taungzin Minthami, one of the Queen’s favourite nurses. She had left her children behind in Burma and was terribly homesick. She decided to go back with her husband.

This reminded everyone of the one thing they’d been trying to forget, which was that left to themselves they would all rather have gone home – that none of them was there because he or she wanted to be. The Queen began to worry that all her girls were going to leave so she began to hand out gifts to her favourites. Dolly was one of the lucky ones, but neither Evelyn nor Augusta received anything.

The two girls were furious at being passed over and they began to make sarcastic comments within the Queen’s hearing. The Queen spoke to the Padein Wun, and he took them into a locked room and beat them and pulled their hair. But this made the girls even more resentful. Next morning they refused to wait on the Queen.

The Queen decided that the matter had passed beyond resolution. She summoned Mr Cox and told him that she wanted to send seven of the girls back to Burma. She would make do by hiring local servants.

Once the Queen had decided on something there was no question of persuading her to change her mind. The seven girls left the next week: Evelyn, Augusta, Mary, Wahthau, Nan Pau, Minlwin, and even Hemau, who was, of all of them, the closest to Dolly in age. Dolly had always thought of them as her older sisters, her family. She knew she would never see them again. On the morning of their departure she locked herself into a room and wouldn’t come out, even to watch their carriage roll out of the gates. U Maung Gyi, the interpreter, took them to the port. When he came back he said the girls had cried when they’d boarded the ship.

A number of new servants were hired, men and women, all local people. Dolly was now one of last remaining members of the original Mandalay contingent: it fell on her to teach the new staff the ways of the household. The new ayahs and maids came to Dolly when they wanted to know how things were done in the Mandalay palace. It was she who had to teach them how to shiko and how to move about the Queen’s bedroom on their hands and knees. It was very hard at first, for she couldn’t make herself understood. She would explain everything in the politest way but they wouldn’t understand so she would shout louder and louder and they would become more and more frightened. They would start knocking things over, breaking chairs and upsetting tables.

Slowly she learnt a few words of Tamil and Hindustani. It became a little easier to work with them then, but they still seemed strangely clumsy and inept. There were times when she couldn’t help laughing – when she saw them trying out their shikoes, for example, wiggling their elbows and straightening their saris. Or when she watched them lumbering around on their knees, huffing and puffing, or getting themselves tangled in their clothes and falling flat on their faces. Dolly could never understand why they found it so hard to move about on their hands and knees. To her it seemed much easier than having to stand up every time you wanted to do something. It was much more restful this way: when you weren’t doing anything in particular you could relax with your weight on your heels. But the new ayahs seemed to think it impossibly hard. You could never trust them to carry a tray to the Queen. They would either spill everything as they tried to get across the room, or else they would creep along so slowly that it would take them half an hour to get from the door to her bed. The Queen would get very impatient, lying on her side and watching her glass of water move across the room as though it were being carried by a snail. Sometimes she would shout, and that would be worse still. The terrified ayah would fall over, tray and all, and the whole process would have to be resumed from the start.

It would have been much easier of course if the Queen weren’t so insistent on observing all the old Mandalay rules – the shikoes, the crawling – but she wouldn’t hear of any changes. She was the Queen of Burma, she said, and if she didn’t insist on being treated properly how could she expect anyone else to give her her due?

One day U Maung Gyi caused a huge scandal. One of the Queen’s nurses went into the nursery and found him on the floor with another nurse, his longyi pulled up over his waist. Instead of scurrying off in shame he turned on his discoverer and began to beat her. He chased her down the corridor and into the King’s bedroom.

The King was sitting at a table rolling a cheroot. U Maung Gyi lunged at the nurse as she went running in. She tripped and grabbed at the tablecloth. Everything flew into the air: there was tobacco everywhere. The King sneezed and went on sneezing for what seemed like hours. When he finally stopped he was angrier than anyone had ever seen him before. This meant still more departures.

With the head nurse thinking herself to be a squirrel and another gone home to Burma, the Queen now had very few dependable nurses left. She decided to get an English midwife. Mr Cox found one for her, a Mrs Wright. She seemed pleasant and friendly enough, but her arrival led to other problems. She wouldn’t shiko and she wouldn’t go down on her hands and knees while waiting on the Queen. The Queen appealed to Mr Cox but the Englishman came out in support of Mrs Wright. She could bow, he said, from the waist, but she needn’t shiko and she certainly wouldn’t crawl. She was an Englishwoman.

The Queen accepted this ruling but it didn’t endear Mrs Wright to her. She began to rely more and more on a Burmese masseur who had somehow attached himself to the royal entourage. He was very good with his hands and was able to make the Queen’s pains go away. But the English doctor found out and made a huge fuss. He said that what the masseur was doing was an affront to medical science. He said that the man was touching Her Highness in unhealthy places. The Queen decided he was mad and declared that she would not send the masseur away. The doctor retaliated by refusing to treat her any more.

Fortunately the Queen’s labour was very short and the delivery quick and uncomplicated. The child was a girl and she was named Ashin Hteik Su Myat Paya.

Everyone was nervous because they knew how badly the Queen had wanted a boy. But the Queen surprised them. She was glad, she said: a girl would be better able to bear the pain of exile.

For a while Mandalay became a city of ghosts.

After the British invasion, many of the King’s soldiers escaped into the countryside with their weapons. They began to act on their own, staging attacks on the occupiers, sometimes materialising inside the city at night. The invaders responded by tightening their grip. There were round-ups, executions, hangings. The sound of rifle-fire echoed through the streets; people locked themselves into their homes and stayed away from the bazaars. Whole days went by when Ma Cho had no call to light her cooking fire.

One night Ma Cho’s stall was broken into. Between the two of them, Rajkumar and Ma Cho succeeded in driving the intruders away. But considerable damage had already been caused; lighting a lamp, Ma Cho discovered that most of her pots, pans and utensils had been either stolen or destroyed. She let out a stricken wail. ‘What am I to do? Where am I to go?’

Rajkumar squatted beside her. ‘Why don’t you talk to Saya John?’ he suggested. ‘Perhaps he’ll be able to help.’

Ma Cho snorted in tearful disgust. ‘Don’t talk to me about Saya John. What’s the use of a man who’s never there when you need him?’ She began to sob, her hands covering her face.

Tenderness welled up in Rajkumar. ‘Don’t cry, Ma Cho.’ He ran his hands clumsily over her head, combing her curly hair with his nails. ‘Stop, Ma Cho. Stop.’

She blew her nose and straightened up. ‘It’s all right,’ she said gruffly. ‘It’s nothing.’ Fumbling in the darkness, she reached for his longyi, leaning forward to wipe the tears from her face.

Often before, Ma Cho’s bouts of tears had ended in this way, with her wiping her face on his thin cotton garment. But this time, as her fingers drew together the loose cloth, the chafing of the fabric produced a new effect on Rajkumar. He felt the kindling of a glow of heat deep within his body, and then, involuntarily, his pelvis thrust itself forward, towards her fingers, just as she was closing her grip. Unmindful of the intrusion, Ma Cho drew a fistful of cloth languidly across her face, stroking her cheeks, patting the furrows round her mouth and dabbing the damp hollows of her eyes. Standing close beside her, Rajkumar swayed, swivelling his hips to keep pace with her hand. It was only when she was running the tip of the bunched cloth between her parted lips that the fabric betrayed him. Through the layered folds of cloth, now wet and clinging, she felt an unmistakable hardness touching on the soft corners of her mouth. She tightened her grip, suddenly alert, and gave the gathered cloth a probing pinch. Rajkumar gasped, arching his back.

‘Oh?’ she grunted. Then, with a startling deftness, one of her hands flew to the knot of his longyi and tugged it open; the other pushed him down on his knees. Parting her legs she drew him, kneeling, towards her stool. Rajkumar’s forehead was on her cheek now; the tip of his skinned nose thrust deep into the hollow beneath her jaw. He caught the odour of turmeric and onion welling up through the cleft between her breasts. And then a blinding whiteness flashed before his eyes and his head was pulled as far back as it could go, tugged by convulsions in his spine.

Abruptly, she pushed him away, with a yelp of disgust. “What am I doing?’ she cried. ‘What am I doing with this boy, this child, this half-wit kalaa?’ Elbowing him aside, she clambered up her ladder and vanished into her room.

It was a while before Rajkumar summoned the courage to say anything. ‘Ma Cho,’ he called up, in a thin, shaking voice. ‘Are you angry?’

‘No,’ came a bark from above. ‘I’m not angry. I want you to forget Ma Cho and go to sleep. You have your own future to think of.’

They never spoke of what happened that night. Over the next few days, Rajkumar saw very little of Ma Cho: she would disappear early in the morning, returning only late at night. Then, one morning, Rajkumar woke up and knew that she was gone for good. Now, for the first time, he climbed the ladder that led up to her room. The only thing he found was a new, blue longyi, lying folded in the middle of the room. He knew that she’d left it for him.

What was he to do now? Where was he to go? He’d assumed all along that he would eventually return to his sampan, to join his shipmates. But now, thinking of his life on the boat, he knew he would not go back. He had seen too much in Mandalay and acquired too many new ambitions.

During the last few weeks he’d thought often of what Saya John’s son, Matthew had said – about the British invasion being provoked by teak. No detail could have been more precisely calculated to lodge in a mind like Rajkumar’s, both curious and predatory. If the British were willing to go to war over a stand of trees, it could only be because they knew of some hidden wealth, secreted within the forest. What exactly these riches were he didn’t know but it was clear that he would never find out except by seeing for himself.

Even while pondering this, he was walking quickly, heading away from the bazaar. Now, looking around to take stock of where he was, he discovered that he had come to the whitewashed facade of a church. He decided to linger, walking past the church once, and then again. He circled and waited, and sure enough, within the hour he spotted Saya John approaching the church, hand in hand with his son.

‘Saya.’

‘Rajkumar!’

Now, standing face to face with Saya John, Rajkumar found himself hanging his head in confusion. How was he to tell him about Ma Cho, when it was he himself who was responsible for the Saya’s cuckolding?

It was Saya John who spoke first: ‘Has something happened to Ma Cho?’

Rajkumar nodded.

‘What is it? Has she gone?’

‘Yes, Saya.’

Saya John gave a long sigh, rolling his eyes heavenwards. ‘Perhaps it’s for the best,’ he said. ‘I think it’s a sign that the time has come for this sinner to turn celibate.’

‘Saya?’

‘Never mind. And what will you.do now, Rajkumar? Go back to India in your boat?’

‘No, Saya.’ Rajkumar shook his head. ‘I want to stay here, in Burma.’

‘And what will you do for a living?’

‘You said, Saya, that if I ever wanted a job I was to come to you. Saya?’

One morning the King read in the newspapers that the Viceroy was coming to Madras. In a state of great excitement he sent for Mr Cox.