The Ice Balloon

If Andrée ever saw the letter, he didn’t mention it in his writings.

He never saw Wise again either. In September, five months after Wise had written to the Times, Andrée “read in the papers that my old friend had gone off on a balloon trip, had been caught in a storm and had never since been heard of.” Wise was lost on September 29, in the Pathfinder, over Lake Michigan. “For his sake I like to believe that he landed unhurt and that he thereafter encountered obstacles which prevented him from coming home,” Andrée wrote.

11

Andrée exemplified a conceit that outlived him—the belief, then nascent, that science, in the form of technology, could subdue the last obstacles to possession of the world’s territories, if not also its mysteries. More or less as psychologists were beginning to regard the deeper orders of the mind, this view saw nature as a shadowy chamber of secrets, a vault, that could be illuminated by the new instruments of science. Its banal applications were typified by devices for the home and the factory—the gramophone, the vacuum cleaner, the arc welding machine—that made life easier, and its sinister ones were the innovations in weapons—the machine gun, the torpedo—and their influence on the tactics of war. For all its worldliness it was also an innocent notion, a response to Romanticism, which had influenced earlier ideas about the Arctic.

Andrée might also be said to have believed in a sort of new dismissiveness that held that anything modern was more desirable than a lived-in idea or artifact. The balloon was superior to the sledge and the ship. The encumbrances of the ocean and the land were absent from the air. The sledge and the ship had failed, the balloon and the air were all possibility. He was the first explorer to head toward the pole unaccompanied by Romantic references.

A hallmark of the Romantic tradition was the notion of the “sublime,” described by Edmund Burke, in A Philosophical Enquiry, which was published in 1757. The sublime was characterized by an astonishment that drove from the mind all other feelings but terror and awe, Burke wrote. This stupefying dread was “the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.” The terror, which was encompassing and prevented reasoning or reflection, was provoked partly by an apprehension of the infinite, and also of the holy. The sublime aroused the deepest feelings the soul could embody, while simultaneously making someone aware that the object which inspired them was a component of a universe that was perhaps largely indifferent, if not unsympathetic, to his well-being both as an individual and a type. Man responded to the sublime because it was glorious—to feel the sublime was to scent the sacred—and because being fitted to feel powerfully, to be profoundly stirred, meant that something of the sublime reverberated within him, otherwise how could he recognize it.

The objects that inspired the sublime were “vast in their dimensions” and “solid, even massive,” Burke wrote. Mountains are what he had in mind, the type of towering, pointy, snow-covered peaks that northern Europeans never have to travel very far to stand beneath. When more became known of the immense and remorseless ground of the Arctic, however, with its darkness, its ship-crushing ice, and terrible cold—a place that was both sanctified and antagonistic—it lent itself even more handsomely to the case.

In one of the enduring Romantic novels, Frankenstein, a young Englishman named Walton is traveling to the Arctic, as a hobby scientist and discoverer—he hopes to find the Northwest Passage and “the secret of the magnet.” He is writing letters to his sister, Margaret, in London. In Russia he writes that a cold wind, which he imagines as coming from the Arctic, has stirred him. “Inspirited by this wind of promise, my day dreams become more fervent and vivid,” he says. “I try in vain to be persuaded that the pole is the seat of frost and desolation; it ever presents itself to my imagination as the region of beauty and delight.” He pictures it as “a land surpassing in wonders and beauty every region hitherto discovered on the habitable globe,” as being “a part of the world never before visited” and “never before imprinted by the foot of man.”

The pole during this period was often personified. Vestiges of the romance surrounding it can be found in the introduction to Arctic Experiences, an account of an expedition made by the ship Polaris toward the pole, published in 1874. “The invisible Sphinx of the uttermost North still protects with jealous vigilance the arena of her ice-bound mystery,” it begins. “Her fingers still clutch with tenacious grasp the clue which leads to her coveted secret; ages have come and gone; generations of heroic men have striven and failed, wrestling with Hope on the one side and Death on the other; philosophers have hypothesized, sometimes truly, but often with misleading theories: she still clasps in solemn silence, the riddle in her icy palm—remaining a fascination and a hope, while persistently baffling the reason, the skill, and courage of man.

“Skirmishers have entered at the outer portals, and anon retreated, bearing back with them trophies of varying value. Whole divisions, as of a grand army, have approached her domains with all the paraphernalia of a regular siege, and the area of attack been proportionately widened; important breaches have been effected, the varied fortunes of war befalling the assailants; some falling back with but small gain; others, with appalling loss and death, have vainly sought escape and safety from her fatal toils. Nor has the citadel been won. ‘UNDISCOVERED’ is still written over the face of the geographical pole.”

12

By the time Andrée announced his plan to leave for the pole he was “altogether of Herculean frame,” one writer wrote. Another described him as “rather stout in appearance,” and as “one of the handsomer men in Sweden.” He was six feet tall, with a large nose, “which people in Sweden regard as an augury of success, and a piercing blue-grey eye,” which made him seem “cut out for command.” A German explorer, Dr. Georg Wegener, met Andrée in London in 1895 and wrote, “The Swedish researcher is a personality cut out of a wood with which world history forms its great men, at the same time daring and balanced, with this strange assurance about progress, with this belief based on the captivating ability to convince, which with all explorers has played the main role, and where the original type is the great, splendid fanatic Columbus.” A French geographer especially interested in glaciers, whose name was Charles Rabot, described Andrée as someone who “created sympathy at first sight. I was attracted towards him, at once I felt confidence in him; at our first meeting he gave me the impression of a strong personality.” Andrée and Rabot spent an afternoon looking for fossils while Andrée asked about the balloons that had carried the mail during the siege of Paris in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War. “Everything that I could recollect of these ascensions interested him,” Rabot said. “That evening we parted as old friends.”

Much of what was written about how Andrée looked and what he was like was written after he had disappeared. He is recalled mostly in tributes, that is, and so he becomes reduced to abstractions and admirable qualities and blurs a little around the edges. He was said to have had few close friends, but among them he was regarded as sociable and devoted. He liked pranks and playing games with children. He had a talent for maxims and penetrating judgments: “Be careful of health, but not of life,” he said. Liberals tended to be tranquil because they believed that a moral force lay behind their positions and so were content to see them unfold, whereas conservatives, he wrote, were combative because they regarded themselves as always under attack.

He practiced a precautionary discipline he called self-hypnosis. Someone whose will was strong, he believed, was always liable to coming under its thrall, and “it is therefore essential to direct one’s will through daily training towards that which one, through judgment and experience, has found to be sensible and therefore beneficial.

“One masters oneself in the same way one masters others:” he wrote, “by cultivating a keen conception of how one should and should not act.” His “cold blooded calmness and realism,” wrote a friend, “were not based on a cold temperament, but on his incessant exercise of self-control.”

He had no ear for music or writing, or any eye for art. In the portrait of him published in The Andrée Diaries, the 1930 account of the voyage and the discovery of the remains, this indifference is described as amounting nearly to “a defect in his character.” Friends who persuaded him to go to the opera or an art exhibition “had every reason to repent of their success, for he always managed to spoil their own pleasure by his remarks and criticisms.” The writer doesn’t mention what those criticisms were, but they were apparently uninformed. When the novelist Selma Lagerlöf was given a prize, Andrée was invited to a dinner in her honor where he was asked if he had read her book, and he said, “No, but I have read Baron Münchhausen”—the German fabulist who had said that he had been to the moon—“and I suppose that it is all the same.” An oaf in cultured company is what he sounds like sometimes, but perhaps he was only trying to deflate manners he regarded as pretentious. As for nature, “he displayed a highly developed sense of beauty, and during his many balloon journeys he greatly enjoyed the magnificent scenery.”

He seemed to have a kind of intelligence that saw patterns in forms that other people found chaotic, and to be able to hold complicated structures and solutions in his head. He cared deeply about how things went together and how they worked and whether their design was efficient. According to The Andrée Diaries, once he decided on an end he did everything he could to attain it. Even so, “no one could weigh every consequence more ruthlessly, more critically than he. He never acted spontaneously, and there was wanting in him the spirit of fresh, impulsive action, but this was compensated for by the sense of security which is conveyed by the actions of an assured, discriminating man. He embodied, in every respect, the ancient phrase: ‘To speak once and stand by one’s word is better than to speak a hundred times.’”

Andrée appears to have been one of those people whose attitudes and habits of mind are literal and firmly formed, so that moving among disciplines is not a matter of broadening oneself by means of new terms so much as applying one’s customary judgments to new circumstances. Such a temperament seeks to encounter the familiar and to assess it or deplore its absence, rather than be influenced and possibly enlarged by what it doesn’t recognize. It is a commanding, not a humble, state of mind, restless rather than engaged, and capacious more than penetrating. An advantage of it is the capacity to interest oneself in a mulitiplicity of subjects and to arrive quickly at personally satisfying determinations. Andrée’s interests were wide-ranging. According to the portrait, he made notes for papers on the influence of new inventions on “every branch of human activity,” from “the general development of mankind” to “language, architecture, military science, the home, marriage, education, etc.” He wrote about scientific topics, in papers such as “Conductivity of Heat in Construction Material” and “Electricity of the Air and Terrestrial Magnetism.” He wrote about social phenomena in others such as “The Education of Girls,” and “Bad Times and Their Causes,” and about miscellaneous topics such as “The Importance of Inventions and Industry for the Development of Language,” and “Directives and Advice for Inventors.” He appeared to feel that nothing that interested him was beyond his ability to have an opinion about it.

13

Once Andrée was grown, the only woman for whom he felt a strong attachment was his mother. “Her rich natural endowments, in which good judgment and sharp intellect dominate such characteristics as are commonly called feminine in this day and time, her remarkable will power and capacity for work, as well as her ability to endure and suffer, remind us of the old Norse women,” he wrote in a notebook. “Despite her seventy-five years she does not seem old. Her face has few wrinkles. It seems to belong rather to a woman of sixty. The impression of power still unshaken is heightened by her voice which lacks the sentimental, pleading tone one so often finds in older women. Her voice harmonizes with her exterior: firm, strong, almost gruff, but with an undertone of kindliness.”

A monument, in other words, erected by a child and tended into adult life—which must have been fatiguing. When Andrée felt himself drawn to a woman, what he called the “‘heart leaves’ sprouting, I resolutely pull them up by the roots,” he wrote. The consequence was that he was “regarded as a man without romantic feelings. But I know that if I once let such a feeling live, it would become so strong that I dare not give in to it.” An acquaintance wrote in a letter that Andrée appeared to have remained a bachelor for the sake of his mother, and for a while they lived with each other. When Andrée was asked why he had never married, he said of any woman who would be his wife that he would not “risk having her ask me with tears in her eyes to abstain from my flights, and at that instant, my affection for her, no matter how strong, would be so dead that nothing could ever bring it back to life.”

Figures from history occasionally rise up from the page as if they had merely been waiting, sometimes impatiently, for someone to speak to them. Andrée comes to life a little resentfully, as if interrupted. Through his devotion to his mother he may have been restricted emotionally from mature relationships with women. It is also possible that he was indifferent to showing, or incapable of expressing, any true warmth to another person, except in the narcissistic fashion of a child. His great mechanical abilities and inclinations toward solitude suggest a temperament that does not effortlessly engage in conventional exchanges, one that might easily be confused or defeated or embittered, and might find objects and tasks more agreeable than people. Not all of us want the same things from life. The mainstream forces its preferences on the minority, partly to sustain those preferences, but that doesn’t necessarily lend them any substance. Nowhere in Andrée’s writings or in the descriptions of him is there an indication of any but a cold-blooded sort of introspection, a capacity for assessing the success or failure of objects and tactics. The territory of feelings seems not to have been hospitable to him.

The only relationship with a woman that Andrée was known to have conducted was an affair with a woman named Gurli Linder, who became in the early twentieth century an admired critic of children’s literature. (Linder wrote the portrait of Andrée in The Andrée Diaries.) The affair, which occupied the last few years before he left—Linder in her brief writings on the matter says 1894 was their best and most untroubled year—was conducted so openly that Linder’s husband, a professor, asked her to behave with more restraint lest she embarrass him among their friends.

14

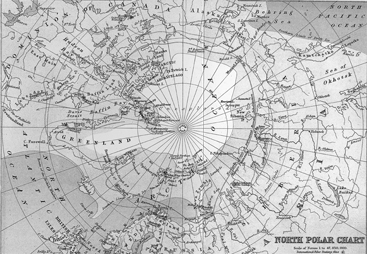

In 1875 an Arctic explorer named Karl Weyprecht, who was from Austria-Hungary, suggested that a series of polar outposts be established by various countries so that science could be done and the results of it shared. Weyprecht felt that polar exploration had become glamorized by its rigors and heroes, and by the pursuit of the unknown at the expense of the intellectual work it might better be doing. Weyprecht’s plan led, in 1882, to the International Polar Year, in which eleven nations established fourteen outposts, twelve in the Arctic and two in Antarctica. Sweden’s outpost was on Spitsbergen. It was overseen by Nils Eckholm, a meteorologist, and, on the recommendation of Professor Dahlander, Andrée’s physics professor, it included Andrée, one of whose tasks was to use a device called a portable electrometer to make notations concerning electricity in the air. The delegation arrived in July of 1882. Andrée was second in command.

No photographs I am aware of show Andrée using the portable electrometer, but from the directions for its use, contained in the paper “Instructions for the Observation of Atmospheric Electricity,” by Lord Kelvin, published in 1901, it is easy to imagine a solitary figure in the daylight of an Arctic summer standing by a tripod about five feet tall. The tripod is not less than twenty yards from any structure that rises above it (“such as a hut or a rock or mass of ice or ship,” Kelvin wrote). To prevent sparks from static electricity leaping from his fur cap or his wool clothes he has covered the cap and his arms with tinfoil attached to a fine wire he holds in the hand that touches the electrometer. The electrometer has its own metal wire to which a lit match is attached, and while the match burns he makes readings by keeping a hair between two black dots, which he has sometimes to squint to see. Andrée performed the task with such resourcefulness, overcoming technical complications that defeated some of the other nations, and so assiduously—he made more than fifteen thousand observations—that the Swedish findings were considered the best among all the nations.

The International Polar Stations, 1882–1883

Courtesy of the Newberry Library, Chicago.

According to The Andrée Diaries, “Andrée also endeavored to find a correlation between the simultaneous variations of aero-electricity and geo-magnetism. “This has been hard work,” he wrote Dahlander, “for it has been necessary to calculate about 5000 values of the total intensity of geo-magnetism.” Meanwhile he made notes about the patterns of drifting snow, which he published in 1883 in “Drift Snow in the Arctic.” Furthermore, to determine whether the yellow-green tinge that appeared in a person’s face at the end of the Arctic winter was a result of the person’s skin having changed color in the dark or of his eyes’ having been affected by the arriving light, Andrée allowed himself to be shut indoors for a month. When he finally went out, it was clear that the pigmentation of his skin had changed. Before his confinement, Andrée wrote, “Dangerous? Perhaps. But what am I worth?” His diligence did not seem to make him well liked, however. His journals often mention that the others are not doing their work properly or are misbehaving, and that he is the only one comporting himself correctly.

“What shall I do when I come home?” Andrée wrote in his journal. In 1885 he was made head of the Technical Department of the Swedish Patent Office in Stockholm, a position he held until he left for the pole. As a kind of ambassador for science and new technology, he traveled in Europe looking for useful patents—he went to the world’s fairs in Copenhagen and in Paris, in 1888 and 1889—especially patents that might reduce drudgery for people who did factory work; he had a social conscience and a conviction that science and new inventions ought to make life less burdensome, that the most useful innovations were applied ones. If people’s lives were easier, he believed, they would be happier, and society would be better, with the result that there would be even more innovations. The man he worked for liked him but thought he was stubborn. He was amused at having pointed out to Andrée that while laws and regulations sometimes prohibited innovations they were nevertheless essential, and having Andrée reply that any law that prevented an innovation was wrong. Andrée’s personality was forceful, and his approach to social and legal change was not subtle. A few years before he left for the pole, he was a member of the municipal council and introduced a motion that the day for people who worked for the city should be reduced to ten hours from twelve, and that the women’s day should be eight hours instead of ten. The proposal failed quickly, and before long, and largely as a consequence, Andrée lost his position on the council.

Between 1876 and 1897 when Andrée left for the pole, the telephone, the refrigerator, the typewriter, the matchbook, the escalator, the zipper, the modern light bulb, the Kodak camera, the gasoline combustion engine, Coca-Cola, radar, and the first artificial textile (rayon) were invented; the speed of light was determined; X rays were first observed and radiation detected in uranium; and Freud and the Austrian physician Josef Breuer began psychoanalysis with the observation in a paper that “Hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences.” Almost quaintly, Andrée embraced modernity by trying to use a half-ancient conveyance in an innovative way.

15

The first balloon plans patented were patented in Lisbon in 1709 by a Jesuit father named Bartolomeu Gusmão. From a balloon, cities could be attacked, he said; people could travel faster than on the ground; goods could be shipped; and the territories at the ends of the earth, including the poles, could be visited and claimed.

Seventy-four years later the first balloon left the ground with passengers, in France. It was built by the Montgolfier brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne. As children they had observed that paper bags held over a fire rose to the ceiling. Using hot air, their first balloon went up without passengers in the country. Their next went up from Paris with a sheep, a duck, and a rooster, because no one knew what the effect of visiting the upper atmosphere would be, or if there was any air in the sky to breathe. Their third balloon went up with two people. The king wanted the first passengers to be criminals, who would be pardoned if they lived, but he was persuaded that a criminal was unworthy of being the first person in the air, and two citizens went instead.

The hydrogen balloon was developed almost simultaneously by a member of the French Academy named Jacques Charles, who had heard of the Montgolfier brothers’ first balloon and mistakenly thought it had used hydrogen. From the place where the Eiffel Tower now is, he sent up a balloon thirteen feet in diameter, also in 1783. Benjamin Franklin was among the audience. The first balloon to go up in England went up in 1784, and the first to crash, when its hydrogen caught fire, crashed in France in 1785.

George Washington watched the first American ascent, in 1793, by a Frenchman who flew from Philadelphia to a town in New Jersey, which took forty-six minutes. Probably the first ascent north of the Arctic Circle was made by a hot-air balloon in July of 1799, built by the British explorer Edward Daniel Clarke, who was visiting Swedish Lapland. He planned the ascent as a kind of spectacular event, “with a view of bringing together the dispersed families of the wild Laplanders, who are so rarely seen collected in any number.” Seventeen feet tall and nearly fifty feet around, and made from white satin-paper, with red highlights, the balloon was constructed in a church, “where it reached nearly from the roof to the floor.” To inflate it Clarke soaked a ball of cotton in alcohol and set the cotton on fire.

The balloon was to go up on July 28, a Sunday, after Mass. The Laplanders, “the most timid among the human race,” Clarke wrote, were frightened by the balloon, “perhaps attributing the whole to some magical art.” The wind was blowing hard, and Clarke thought it would ruin his launch, but so many Laplanders had showed up he “did not dare to disappoint them.” The Laplanders grabbed the side of the balloon as it was filling, and tore it. They agreed to remain in town, with their reindeer, while it was mended. Meanwhile “they became riotous and clamorous for brandy.” One of them crawled on his knees to the priest to beg for it.

When the balloon was released that evening, the Lapps’ reindeer took off in all directions, with the Lapps running after them. It landed in a lake, took off again, then crashed. The Lapps crept back into town.

Hydrogen balloons are absurdly sensitive to air pressure, temperature, the density of their gas, and the weight they have aboard. Pouring a glass of water over the side of a balloon, or a handful of sand, will make it rise. A shadow falling on it will cause it to descend. A balloon has an ideal (and theoretical) equilibrium, at which it would float indefinitely, assuming it didn’t lose gas through the envelope, but that point is impossible to sustain because the balloon’s circumstances keep changing. A rising balloon doesn’t slow as it approaches equilibrium; from momentum, it continues. Having passed the point of stability, it sheds hydrogen, because the gas has expanded as the pressure of the air has lessened, and the balloon sinks, passing the point on its fall. Shedding the perfect amount of ballast at the ideal rate might settle the balloon exquisitely, but shedding weight also causes the balloon to rise. If it rises too quickly the only corrective might be to release hydrogen, which the pilot would rather retain. Part of the skill of flight, particularly of a flight that is to last a long time, is to manage the altitude with sufficient temperance that little gas or ballast is lost. Enough ballast must be kept to land the balloon properly. Theoretically a balloon might be operated more stably at night, since the temperature does not change as clouds intersect the sun.