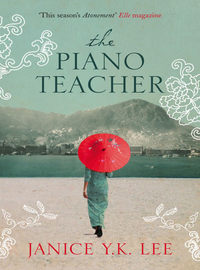

The Piano Teacher

‘Haven’t the foggiest,’ she says easily. ‘He’s the Tailor. But I know where the shop is, or my driver does, and we’re the best of friends. Do you fellows prefer orange or a very bright pink as colours?’

They decide on olive green (‘So boring,’ the women sigh) with orange stripes (a concession), and Trudy asks who is to measure the men.

They suggest her.

She accepts (‘Isn’t there something about dressing left?’ she asks innocently), then says that Will can measure in her stead. Trudy’s frivolity, Will has noticed, has boundaries.

Sophie Biggs is trying to interest everyone in moonlight picnics. ‘They’re ever so much fun,’ she says. ‘We take a steamboat out, with row boats, and when we reach the islands we row everyone ashore with the provisions and a guitar or an accordion or something.’ Sophie is a large girl and Will wonders if she is a secret eater because she eats tiny portions when she is out. Now, she is poking her spoon in the vichyssoise.

Trudy sighs. ‘It sounds like so much labour,’ she says. ‘Wouldn’t it just be easier to have a picnic at Repulse Bay?’

Sophie looks at her reproachfully. ‘But it’s not the same,’ she says. ‘It’s the journey.’

Sophie’s husband claims to be in shipping, but Will thinks he’s in Intelligence. When he tells Trudy this, she cries, ‘That big lout? He couldn’t detect his way out of a paper bag!’ But Jamie Biggs is always listening, never talking, and he has a watchful air about him. If he’s that obvious, Will supposes he’s not very good. After Charles Pottinger left last year, someone had told Will that he was Intelligence. He hadn’t been able to believe it. Charles was a big, florid man who drank a lot and seemed the very soul of indiscretion.

Edwina Storch, a large Englishwoman who is the headmistress of the good school in town, has brought her constant companion, Mary Winkle, and they sit at the end of the table, eating quietly, talking to no one but each other. Will has seen them before. They are always around, but never say much.

Over dessert – trifle – Jamie says that all Japanese residents have been sent secret letters about what to do in case of an invasion, and that the Japanese barber chap in the Gloucester Hotel has been spying. The government is about to issue another edict that all wives and children are to be sent away without exception, but only the white British, those of pure European extraction, get passage on the ships. ‘Doesn’t affect me.’ Trudy shrugs, although she holds a British passport. Will knows that if she wanted, she could get on to a boat – her father always knows someone. ‘What would I do in Australia?’ she asks. ‘I don’t like anybody there. Besides, it’s only for pure English – have you ever heard of anything so offensive?’

She changes the subject. ‘What would happen,’ she asks, ‘if two guns were pointed at each other and then the triggers were pulled at the same time? Do you think the two people would get hurt or would the bullets destroy each other?’

There is a lively discussion about this that Trudy is soon bored with. ‘For heaven’s sake!’ she cries. ‘Isn’t there something else we can talk about?’ The group, chastised, turns to yet other subjects. Trudy is a social dictator and not at all benevolent. She tells someone recently arrived from the Congo that she can’t imagine why anyone would go to a Godforsaken place like that when there are perfectly pleasant destinations, like London and Rome. The traveller actually looks chagrined. She tells Sophie Biggs’s husband that he doesn’t appreciate his wife, and then she tells Manley she loathes trifle. Yet, no one takes offence; everyone agrees with her. She is the most amiable rude person ever. People bask in her attention.

At the end of dinner, after coffee and liqueurs, Manley’s houseboy brings in a big bowl of nuts and raisins. Manley pours brandy over it with a flourish and Trudy lights a match and tosses it in. The bowl is ablaze instantly, all blue and white flame. They try to pick out the treats without burning their fingers, a game they call Snapdragon.

Going to the bathroom later, Will glimpses Trudy and Victor talking heatedly in Cantonese in the drawing room. He hesitates, then continues on. When he returns, they are gone and Trudy is already back at the table, telling a bawdy joke.

After, they go to bed. Manley has given them a room next to his and they make love quietly. With Trudy, it is always as if she is drowning – she clutches at him and burrows her face into his shoulder with an intensity she would make fun of if she saw it. Sometimes the shape of her fingers is etched into his skin for hours afterwards. Later, Will wakes up to find Trudy whimpering, her face lumpy and alarming; he sees that her face is wet with tears.

‘What’s wrong?’ he asks.

‘Nothing.’ A reflex.

‘Did Victor upset you?’ he asks.

‘No, no, he wants to … My father …’ She goes back to sleep. When he throws the blanket over her, her shoulders are as cold and limp as water. In the morning, she remembers nothing, and mocks him for his concern.

In the following weeks, the war encroaches – wives and children, the ones who had ignored the previous evacuation, leave on ships bound for Australia, Singapore. Trudy is obliged to make an appearance at the hospitals to prove she is a nurse. She undergoes training, declares herself hopeless, and switches to supplies instead. She finds the stockpiling of goods too amusing. ‘If I had to eat the food they’re storing, I’d shoot myself,’ she says. ‘It’s all bully beef and awful things like that.’

The colony is filled with suddenly lonely men without wives; they gather at the Gripps, the Parisian Grill, clamour to be invited to dinner parties at the homes of those few whose wives remain. They form a club, the Bachelors’ Club (‘Why do the British so love to form clubs and societies?’ Trudy asks. ‘No, wait, don’t say, it’s too grim.’) and petition the governor to bring back the women. Others, more intrepid, turn up suddenly with adopted Chinese ‘daughters’ or ‘wards’, dine with them and drink champagne, then disappear into the night. Will finds it amusing, Trudy less so. ‘Wait until I get my hands on them,’ she cries, while Will teases her about which Chinese hostess would soon get her claws into him.

‘You’re like a leper, darling,’ she counters. ‘You British men are going out of fashion. I might have to find myself a Japanese or German beau now.’

Later Will remembers this time so clearly, how it was all so funny and the war was so far away, yet talked about every day, how no one really thought about what might really happen.

September 1952

Claire was waiting for the bus after Locket’s piano lesson when Will Truesdale drove up in the car. ‘Would you like a lift?’ he asked. ‘I’ve just finished for the day.’

‘Thank you, but I couldn’t put you out,’ she said.

‘Not at all,’ he said. ‘The Chens don’t mind if I take the car home for the night. Most employers want their cars left at home and the chauffeur to take public transport home, so it’s no bother.’

Claire hesitated, then got into the car. It smelled of cigarettes and polished leather. ‘It’s very kind of you.’

‘Did you have a good time at the Arbogasts’ the other day?’ he asked.

‘It was a very nice party,’ she said. She had learned not to be effusive, that it marked her as unsophisticated.

‘Reggie’s a good sort,’ he said. ‘It was nice to meet you there, too. There are too many of those women who add to the din but not to anything else. You shouldn’t lose that quality of seeing everything new for what it is. All the women here …’

He drove well, she thought, steady on the steering-wheel, his movements calm and unhurried.

‘You’re not wearing the perfume you had on the other day,’ he said.

‘No,’ she said, wary. ‘That’s for special occasions.’

‘I was surprised that you had it on. Not many English wear it. It’s more the fashionable Chinese women. They like its heaviness. English women like something lighter, more flowery.’

‘Oh, I wasn’t aware.’ Claire’s hand went unconsciously to her neck, where she usually dabbed it on.

‘But it’s lovely that you wear it,’ he said.

‘You seem to know a lot about women’s scents.’

‘I don’t.’ He glanced over at her, his eyes dark. ‘I used to know someone who wore it.’

They rode in silence until they arrived at her building.

‘You teach the girl,’ he said, as she was reaching for the door, his voice suddenly urgent.

‘Yes, Locket.’ She said, taken aback.

‘Is she a good student?’ he asked. ‘Diligent?’

‘It’s hard to say,’ she said. ‘Her parents don’t give her much of a reason to do anything so she doesn’t. Very typical at that age. Still, she’s a nice enough girl.’

He nodded, his face unreadable in the dark interior of the car.

‘Well, thank you for the lift,’ she said. ‘I’m most grateful.’

He raised a hand, then drove off into the gathering dusk.

And then a bun. A bun with sweetened chestnut paste. That was how they met again. She had been walking up Elgin Street to where there was a bus stop, when it started to pour. The rain – huge, startling plops – fell heavily and she was soaked through in a matter of seconds. Looking up at the sky, she saw it had turned a threatening grey. She ducked into a Chinese bakery to wait out the storm. Inside, she ordered tea and a chestnut bun, and as she turned to sit at a small, circular tables, she spotted Will Truesdale, deliberately eating a red bean pastry, staring at her.

‘Hello,’ she said. ‘Caught in the rain, too?’

‘Would you like a seat?’

She sat down. In the damp, he smelled of cigarettes and tea. A newspaper was spread in front of him, the crossword half finished. A fan blew at the pages so they ruffled upwards.

‘It’s coming down cats and dogs. And so sudden!’

‘So, how are you?’ he asked.

‘Fine, thank you very much. I’ve just come from the Liggets’, where I borrowed some patterns. Do you know Jasper and Helen? He’s in the police.’

‘Ligget the bigot?’ He wrinkled his forehead.

She laughed, uncomfortable. His hand thrummed the table, though his body was relaxed. ‘Is that what you call him?’ she asked.

‘Why not?’

He did the crossword as she ate her bun and sipped her tea. She was aware of her mouth chewing, swallowing. She sat up straight in her chair.

He hummed a tune, looked up. ‘Hong Kong suits you,’ he said.

She coloured, started to say something about being impertinent but her words came out muddled.

‘Don’t be coy,’ he said. ‘I think …’ he started, as if he were telling her life story. ‘I imagine you’ve always been pretty but you’ve never owned it, never used it to your advantage. You didn’t know what to do about it and your mother never helped you. Perhaps she was jealous, perhaps she, too, was pretty in her youth but is bitter that beauty is so transient.’

‘I haven’t the slightest idea what you’re talking about,’ she said.

‘I’ve known girls like you for years. You come over from England and don’t know what to do with yourselves. You could be different. You should take the opportunity to become something else.’

She stared at him, then pushed the bun wrapper around on the table. It was slightly damp and stuck to the surface. She was aware of his gaze on her face.

‘So,’ he said. ‘You must be very uncomfortable. My home is just up the way if you want to change into some dry things.’

‘I wouldn’t want to …’

‘Do you want my jacket?’

He was looking at her so intently that she felt undressed. Was there anything more intimate than being truly seen? She looked away. ‘No, I …’

‘No bother at all,’ he said quickly. ‘Come along,’ and she did, pulled helplessly by his suggestion.

They climbed the steps, now damp and glistening, the heat already beginning to evaporate the moisture. Her clothes clung to her, her blouse sodden and uncomfortable against her shoulder-blades. In the quiet after the rain, she could hear his breathing, slow and regular. He used his cane with expertise, hoisting himself up the stairs, whistling slightly under his breath.

‘In good weather, there’s a man who sells crickets made of grass stalks here.’ He gestured to a street corner. ‘I’ve bought dozens. They’re the most amazing things, but they crumble when they dry up, crumble into nothing.’

‘Sounds lovely,’ Claire said. ‘I’d like to see them.’

They went into his building, and walked up some grungy, industrial stairs. He stopped in front of a door. ‘I never lock my door,’ he said suddenly.

‘I suppose it’s safe enough in these parts,’ she said.

Inside, his flat was sparsely furnished. She could see only a sofa, a chair, and a table on bare floor. When they stepped in, he took off his soaking shoes. ‘The boss says I can’t wear shoes in the house.’

Just then, a small, wiry woman of around forty came in. She was wearing the amah uniform of a black tunic over trousers.

‘This is the boss, Ah Yik,’ he said. ‘Ah Yik, this is Mrs Pendleton.’

‘So wet,’ the little woman cried. ‘Big rain.’

‘Yes,’ Will said. ‘Big, big rain.’ Then he spoke to her rapidly in Cantonese.

‘Tea for Missee?’ Ah Yik said.

‘Yes, thank you,’ he said.

The amah went into the kitchen.

They looked at each other, uncomfortable in their wet and rapidly cooling clothes.

‘You are proficient in the local language,’ she said, more as a statement than a question.

‘I’ve been here more than a decade,’ he said. ‘It would be a real embarrassment if I couldn’t meet them halfway by now, don’t you think?’ He took a tea towel off a hook and rubbed his head. ‘I imagine you’d like to dry off,’ he said.

‘Yes, please.’

She sat down as he left the room. There was something strange about the room, which she couldn’t place until she realized there was absolutely nothing decorative in the entire place. There were no paintings, no vases, no bric-a-brac. It was austere to the point of monkishness.

Will came back with a towel and a simple pink cotton dress. ‘Is this appropriate?’ he asked. ‘I’ve a few other things.’

‘I don’t need to change,’ she said. ‘I’ll just dry off and be on my way.’

‘Oh, I think you should change,’ he said. ‘You’ll be uncomfortable otherwise.’

‘No, it’s quite all right.’

He started to leave the room.

‘Fine,’ she said. ‘Where should I …’

‘Oh, anywhere,’ he said. ‘Anywhere you won’t scandalize the boss, that is.’

‘Of course.’ She took the dress from him. ‘It looks about the right size.’

‘And there’s a phone out here if you want to ring your husband and let him know where you are,’ he said.

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘Martin’s in Shanghai, actually.’ And she went into the bathroom.

It was small but clean, with a frosted-glass window high above the lavatory. It was the wavy, pebbled kind, with chicken wire running through it. Next to that, a small fan was set into the wall with a string attached. It was humid, with the rain splattering outside, and the musty feel of a bathroom that hadn’t got quite aired out enough after baths. Next to the bath, there was a low wooden stool with a steel basin on top. Claire leaned forward into the mirror. Her hair was messy, the fine blonde strands awry, and her face was flushed, still, with the exertion of climbing up the hill. She looked surprisingly alive, her lips red and plump, her skin glowing with the moisture. She undressed, dropping her soaked blouse to the floor, which sloped to a drain in the middle. She towelled herself and pulled the dress over her hips. It was snug, but manageable. Why did Will have a dress lying around? It was very good quality, with perfectly finished seams and careful needlework. She went out to where he was sipping from a Thermos of tea.

‘Fits you well,’ he said neutrally.

‘Yes, thank you very much.’

All of a sudden, Claire couldn’t bear it. She couldn’t bear this man with his odd pauses and his slightly mocking tone.

‘Something to eat, perhaps?’ he said. ‘Ah Yik makes a very good bowl of fried rice.’

‘I think I’d better leave,’ she said.

‘Oh,’ he said, taken aback. She took satisfaction from his surprise, as if she had won something. ‘Of course, if you’d rather.’

She got up and left, putting her shoes on at the door while Will stayed in the living room. When she turned to say goodbye, she saw he was reading a book. This infuriated her. ‘Well, goodbye, then,’ she said. ‘I’ll have my amah return the dress. Thank you for your hospitality.’

‘Goodbye,’ he said. He didn’t look up.

That night, after dinner, she couldn’t relax. Her insides seemed too large for her outside, a queer sensation, as if all that she was feeling couldn’t be contained inside her body. As Martin was still away she put on her street clothes and got on the bus to town, bumping over the roads, elbow out of the window, open to the warm night air. She disembarked in Wanchai, where there seemed to be the most activity. She wanted to be among people, not alone. The wet market was still open, Chinese people buying their cabbages and fish, pork hanging from hooks, sometimes a whole pig’s head, red and bloody, dripping on to the street. This was the peculiarity of Hong Kong.

If she walked ten minutes towards Central, all would be civilized, large, quiet buildings in the European classical style, and wide, empty streets, yet here the frenetic activity, narrow alleys and smoky stalls were another world. All around her, people called to each other loudly, advertising their wares, a smudge-faced child playing in the street with a dirty bucket. A pregnant woman carrying vegetables under her arm jostled her and apologized, her movements heavy and clumsy. Claire stared after her, wondering how it felt to have a child inside you, moving around. A young couple, arms linked, sat down at a noodle stand and broke out loudly in laughter.

Next to her, a wizened elderly lady tugged at Claire’s arm. Dressed in the grey cotton tunic and trousers that most of the local older women seemed to favour, she had a small basket of tangerines on her arm.

‘You buy,’ she said. She smelled like the white flower ointment the locals used to fend off everything from the common cold to cholera. One of her teeth was grey and chipped, the others antique yellow. The woman’s brown face was a spider web of deeply etched lines.

‘No, thank you,’ said Claire. Her voice rang out like a bell. It seemed that its sound stilled the bustle around her for a moment.

The woman grew more insistent.

‘You buy! Very good. Fresh today.’ She pulled at Claire’s arm again. Then she reached up and touched Claire’s hair like a talisman. The local Chinese did that sometimes, and while it had been frightening the first time, Claire was used to it now.

‘Good fortune,’ said the old woman. ‘Golden.’

‘Thank you,’ said Claire.

‘You buy!’ the woman repeated.

‘I’m not looking for anything today, but thank you very much.’ The hum around her resumed. Claire continued walking. The old woman followed her for a few yards, then shambled off to find more promising customers.

Why not buy a tangerine from an old lady? Claire thought suddenly. Why not? What would happen? She couldn’t think why she had declined, as if her old English self, with its defences and prejudices, was dissolving in the foetid environment around her.

She turned, but the woman had already disappeared. She breathed deeply. The smells of the wet market entered her, intense and earthy. Around her, Hong Kong thrummed.

And then, suddenly, he was everywhere. She saw Will Truesdale waiting for the bus, at Kayamally’s, queuing outside the cinema. And though he never saw her, she always lowered her head, willing him not to notice. And then she’d glance up, to see if he had. He had a way of seeming completely contained within himself, even when he was in a crowd. He never looked around, never tapped his feet, never looked at his watch. It seemed he never saw her.

When she went for Locket’s lesson on Thursdays, she found herself looking for Will Truesdale. She heard the amahs laughing at his jokes in the kitchen, and she saw his jacket hanging in the hall, but his physical presence was elusive, as if he slipped in and out, avoiding her. She lingered at the end of her lesson, but she never saw him or the car.

Then they were at the beach the next weekend. She hardly knew how it had happened. She had come home. The phone rang. She picked it up.

‘I’ve a friend with one of those municipal beach huts,’ he said. ‘Would you like to go bathing?’ As if nothing had happened. As if she would know who it was by his voice.

‘Bathing,’ she said. ‘Where?’

‘On Big Wave Bay,’ he said. ‘It’s a perk for the locals but they don’t mind if we sign up as well. It’s a lottery system and you get a cottage for the season. A group of us usually get together to do it and swap weekends. It’s quite nice.’

She shut her eyes and saw him: Will, the difficult man, with his thin shoulders and grey eyes, his dark hair that fell untidily into his eyes, a man who stared at her so intently she felt quite transparent, a man who had just asked her to go bathing with him, unaccompanied. And she opened her eyes and said, yes, she would join him at the beach that Sunday.

Martin was away for three weeks and he had telegraphed from Shanghai to let her know he would be delayed for some time. He was on a tour of major Chinese cities to inspect their water facilities, which he expected to be very primitive.

And so, it was water. She wondered why she hadn’t thought of it before. How it rendered everything changed. She was a different woman in a different sphere. And Will! The way he plunged in, without a thought, his limp gone, dissolved into the current. He was a fish, darting here and there, swimming out into the horizon, further than she would ever go.

They were the only Europeans at the beach. The water was still warm from the summer, the air just starting to crisp. The hut was a simple structure with wooden cupboards and woven straw mats. The sand was fine, speckled with black, and small, withered leaves. Families picnicked around them, chattering loudly, small children scrambling messily about. He wanted to go out to the floating diving docks, some two hundred yards out. When she said she couldn’t, that it was too far, he said of course she could, and so she did. Out there, they climbed on to the rocking circle and sunned themselves like seals. He lay in the sun, eyes closed, as she watched surreptitiously, his ribs jutting out, his body pocked with unnamed scars of unknown origin. He wore short cotton trousers that were heavy with water. He wasn’t the type to wear a bathing suit.

It was hot, hot. The sun hid behind clouds for brief moments, then blazed out again. There was no cover. She wished for a cold drink, a tree for shade, both of which seemed impossibly far away on the shore.

‘We should have swum out with a Thermos of water,’ she said.

‘Next time,’ he said, eyes still shut.

‘Tell me your story,’ she said, after allowing herself a minute to digest what that meant. She was still vibrating with the strangeness of the situation – that she was at the beach with a man, intentions unknown.

‘I was born in Tasmania, of Scottish stock,’ he said mockingly, as if he were starting an autobiography. He sat up and crossed his legs as if he were a swami.

‘Why?’ she said.

‘My father was a missionary and we lived everywhere,’ he said. ‘I’ve only been to England once, and loathed it. My mother was a bit of a Bohemian and she had some money from her family so we were set in that way.’

Hong Kong was full of people like Will, wandering global voyagers who had never been to Piccadilly Circus. Claire had been just once, and there had been an old man in tattered clothes who would shout, ‘Fornicators!’ at everyone who passed.

‘And how did you learn?’ she asked.