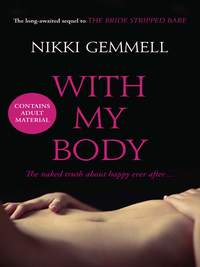

With My Body

Hugh has said it’s good you’re Australian in this place; your accent can’t be placed, you can slip effortlessly from lower class to upper, can’t be pinned down. You know it’s good Hugh is not Australian for he can’t nail the broad flatness of tone that any Aussie East Coaster would recognise as originally from the sticks. The bush has never been completely erased from your voice; wilfully some remnant clings to it. Your vowels have been softened by Sydney, yes, but they still carry, faintly, the red-neck boondocks in their cadence. England hasn’t left a trace.

You will always be an outsider here. You revel in not-belonging, enjoy the high vantage point. Marvel, still, at the strict sense of place, of class they cannot breach – the fishing and shooting, the villas in France, the stone walls that collect the cold and the damp, the wellies even in July, the jumpers in August, the hanging sky like the water-bowed ceiling of an old house. How can it hold so much rain, cry so much? Days and days and days of it and at times you just want to raise your arms and push up the clouds, run. Hugh will never move to Australia, he has a blinkered idea of it as the end of the earth and deeply uninteresting, really – that the only culture you’ll find there is in a yoghurt pot.

You can see your whole future stretching ahead of you now until your body is slipped into this damp black earth, the years and years of sameness ahead. Once, long ago, you never wanted to be able to do that, curiosity was your fuel, the unknown. You carry your despair in you like an infection that cannot be shaken.

But now. A dangerous will inside you to crash catastrophe into your life, somehow, God knows how – or with whom. It’s been brewing for years; it’s something about reaching your forties and seeing all that stretches ahead. You’ve never been fully unlocked with Hugh and bear responsibility for that, entirely.

For always wearing a mask. For not being entirely honest. For never showing him your real self.

Lesson 9

Unhappiness of soul – a state of being often as unaccountable as it is irrational

‘How are you?’ the lovely, cheeky Bengali man in your newsagency asked before school pick up today.

You replied, distracted, ‘I have no idea.’

The ultimate flaky mum, you know he thought.

But it was the truth. You have no idea. Have lost the woman you once were. Cannot simplify your life. Had so much energy for so much, once; now your days are taken up with so many bitsy, consuming, domestic things. You catch yourself talking aloud as you walk away down the High Street. Is it madness or preoccupation or mere motherhood. In a window reflection you gasp at yourself scowling, jaw set. There’s the niggle that now you’re married you are somehow less. Just the little wife. Hugh doesn’t mean to convey that but he does. There’s a subtle and discernible loss of confidence, so insidious, as you lean on another for so much and you never did that, once. As you have somehow allowed over the years your petrol tank to be filled and restaurant dinners to be decided for you, sweets secreted to your kids, Nintendo Wiis gleefully bought behind your back, theatre tickets purchased for plays you don’t like.

You cannot explain how circumstances have closed over you, how you became a woman who lost her voice.

But you know there’s only one person who can haul you out.

It is five o’clock.

The potatoes have to be peeled and the toilet unblocked; it’s probably a plastic toy, it’s becoming a habit with Pip, your youngest.

You have to change this life, somehow, or something in you will implode like a depth charge way beneath the surface.

Lesson 10

There are very few families whose internal mismanagement and domestic unhappiness are not mainly the fault of the mistress

Nine p.m. Just the dishwasher to unpack now and then you’ll draw your bath and unclench, at last, in the warmest room in the house, the main bathroom.

The phone. Susan. A mum from the boys’ school and you don’t know how it came to this: a Susan so entwined in your life. Rexi is friends with her eldest, Basti. You met when the boys were in the same nursery and then they moved to primary school together, have known each other for years. It is assumed. But you became friends before you realised how unsettling she is. A mother with an overdeveloped sense of her own rightness, with everything, and there’s something so undermining about that.

Every conversation, to Susan, is a form of competition; there must always be the moment of triumph. When she’s first seen every morning, at the school gate, she forces you to say how lovely her little girl looks, to compliment.

‘Look at Honor, she dressed herself today, doesn’t she look gorgeous?’

‘Where’s Honor, is she hiding on my shoulders?’

‘Isn’t she beautiful?’

Yes of course, and you are a woman who does not have a daughter but it would never cross Susan’s mind that the keenness for a girl once sliced through you like a ragged bit of tin; you can’t deny there was a moment of disappointment at each subsequent son who appeared from your womb – just a moment, wiped as soon as you held them to your breast. And now, every day at the school gate, there is the ritual noticing of what you do not have, every day this conversation you have somehow allowed in your life.

Susan is obsessed by her children. Like no other woman you know. Always talking about how good her Basti is – at maths, swimming, art, he’s just swum four laps, helped plant her herb garden, is never sick, always good – not one of those naughty ones.

You always cringe at this – your boys are boys, you adore them but they are not always the best; often your heart is in your mouth when your family is with other people, about what may be said, knocked over, who may be shouted at. Susan is critical of your Rexi whenever he’s had a play date. Always, on the doorstep when you pick him up, you have to submit to her little ritual of complaint. The only time you can ever remember her complimenting your eldest was when she said, in wonder, ‘He’s good looking … now.’ Now. Your beautiful, sunny, ravishing boy, from day one.

‘Rex didn’t eat his food … wouldn’t play with Honor … was very loud …’

You have allowed it, for so long – Susan’s reward for taking one son off your hands, for giving you a blessed break; it means one less child for a few hours and you both know how needed that is in your life, a tiny sliver of extra space.

Lesson 11

A state of sublime content and superabundant gaiety – because she always had something or other to do.

If not for herself, then her neighbour.

It is nine-fifteen and Susan is still on the phone and inwardly, at her voice, there is a tightening in your stomach, a knot – what has her Basti excelled at today, what triumph has to be endured? And your head is full of the ‘Shout Book’ you have just discovered under your middle child’s bed. Jack has recorded, meticulously, every time he is yelled at. By you. In writing neater than it’s ever been at school.

Saturday: 14th January. 2 times.

Sunday: 15th January. AMAZING. Nothing.

Monday: 16th January. 3 times.

Devastation. Today it was all to do with him wearing a good shirt to his grandmother’s tomorrow, for her birthday tea.

‘I hate that button shirt so much it makes me walk backwards,’ he had shouted.

You laughed at the time and later jotted it down; for what, God knows. You had to laugh, they give you so much and don’t even know it. These bouncy, shiny little scamps fill every corner of your life, plump it out; you love them so consumingly but you’re not sure they believe it, Jack most of all, your middle child you worry will one day slip through the cracks.

‘Please, God, stop Mummy shouting,’ was his prayer tonight.

‘Don’t!’ came his muffled protest from under the duvet when you tried to tickle him into giggles, to kiss away all your guilt, but he recoiled as if your touch would scald him which only made you want to caress him, cuddle him, envelop him all the more.

Susan is prattling on, she wants you to do the coffee before the class assembly on Monday and didn’t catch you today. She is president of the P.T.A., you are a class rep, this is the new world you have thrown yourself into with the zeal you once reserved for law. You’re deeply embedded in this intense little microcosm, yet feel sick every day now as you approach the gates for pick up. Wear a mask of joy – you have perfected it but if only they knew of your relief when for some reason, too rarely, you don’t have to be there. It’s your twice daily torture and you feel ill, sometimes, as you near the school gates. You wait in the car so you’re not standing there early, having to talk. Filling up afternoons with play dates for the boys so they’re not missing out and filling up your own evenings with drinks and dinners with your mummy friends for the same reason and you need the solace and release of using your brain, somehow. You’ve been with some of these women for over five years now. And their flaws are getting worse as they age – as are yours; it feels like you are all hardening into your weaknesses and you’ve got years of this school run ahead of you. The competitiveness, petty power games, boasting, one-upmanship; sometimes you feel like you’re ten again, back in the school yard. It’s stealing who you really are, who you became, once.

Lesson 12

Beware the outside friend who only rubs against one’s angles

Your shout book.

What Mothers Do (or, The Tyranny of the School Gate)

Sometimes you just want to scream at these women, at the height of all the pettiness (usually towards the end of term when everyone’s frazzled). Can’t we all just value each other? Please? It’s hard, for every one of us, you’re sure of that.

And then, specifically, there’s Queen Susan:

If you were content, none of this would infect you; it would just roll away like water off a duck’s back. But one woman, this woman, has become a focus for all your frustration and you know it’s unfair and paranoid and ridiculous, she’s a good person, you’re just jealous of her position and the way she’s worked out her life and it’s eating you up, can’t escape it. But you’d be happy to never see her again. Would never have befriended a Susan in your former existence, are not uplifted by her in any way; your heart doesn’t skip with happiness to see her and you need heart-lifters around you now, more than ever – it feels like you’re becoming more thin-skinned and vulnerable as you age. How can that be? That the great, raw wounds inflicted by others in the distant past are sharpening now, in middle age. You can’t gouge them out and you have no idea why; have lost your voice, your strength.

Lesson 13

Friendship – a bond, not of nature but of choice, it should be maintained, calm, free, and clear, having neither rights nor jealousies, at once the firmest and most independent of all human ties

Your hand is straying into your pants, thinking of other things entirely, school dads, their spark. How one in particular, Ari, would spring you alive, back to the woman you once were. Ari, yes, he’d have the knowledge, the instinct; but you’d never do it. God no, the mess of it. Susan is still in your ear, telling you that Basti is just about to pass his first flute exam, can pick up any piece of music and just play it, he amazes her. (Rexi, God love him, is on page six of his guitar book and unlikely to progress.) And the coffee morning, ‘Can you run it, babes?’ Of course, yes. Susan will bake some muffins for you: ‘I know you’re not good at that bit.’

She is constantly baking, her house a show place, her children spotless – yours are the ones who sometimes wear grubby t-shirts you’ve flipped inside out, have cereal for dinner and Coca-Cola as a treat. In Susan’s kitchen is a huge notice board in an ornate frame crammed with certificates of achievement and baby photos and colourful kids’ drawings. The occasional certificates your own children get are lost in piles, somewhere, along with school reports and photos and Santa lists and they will all be sorted, sometime. Long ago, you were in control of your career, your friends, your life; you never feel in control within motherhood. The guilt at so much.

The time you folded up the push chair and placed it in the boot, only to hear a squeak – baby Pip still in it.

The time Jack rolled off the bed as you were changing his nappy and ended up with a dint in his skull.

The birthday cakes from Tesco, year after year.

The computer games that keep them all riveted, baby included.

The occasional McDonald’s, three quarters of an hour’s drive away on a Sunday night.

Basti, of course, has never had it in his life. He tells you this when he comes to your house. He has inherited his mother’s heightened sense of censorious rightness, about everything in his life, and you fear for what’s ahead of him, how the wider world will chip away at that. Meanwhile Susan bustles about in her flurry of energy, a tiny, dark sparrow of efficiency with an enormous, puffed chest, making you feel deficient in response, that you’re always running and never quite catching up. Have had no role model in life for this. The best mothers are those who had bad mothers, you think, because they know what not to do – but what if you never had a mother? If she died before she was lodged in memory.

Susan’s voice veers you back.

‘Wasn’t that homework hard today? Basti got it, eventually.’

‘Rexi took a while. I had to snap off the TV just to get him to the table …’

‘We don’t miss ours. The kids never ask for it.’

A pause. ‘Lucky you.’

Television, of course, is babysitting for you, your guilty secret. And you didn’t notice exactly what Rexi was doing in his maths book.

‘Just checking you’re still on for Basti this Thursday?’

You’re always scrupulously generous with play dates; it’s why the routine works.

‘Of course … can’t wait.’

‘Did you get the notice about nits? I know you never check their schoolbags, just reminding you. Basti’s never had them. I don’t know who it is …’

You shut your eyes, your knuckles little snow-capped mountains around the phone. Because of bath time, several hours earlier – all the boys, even Pip – and dragging out the lice with all their tiny, frantic legs. And Jack has a pathological aversion to nits, almost vomits with the horror of them, yells like you’re scalping him. Then the pleas, the threats, to finish the homework due tomorrow, to stop the Wii, get to bed. Rexi storming off in frustration, his arms over his head. You feel, sometimes, he’s a great open wound that you’re pouring your love and puzzlement into. What’s going on in there? Does it ever even out? He’s only nine. His teacher says it’s something to do with boys about this age, from seven onwards, their teeth coming through; there’s a huge psychological change in them, hormones swirling. Does he mellow with age, does he strengthen? Is he too much like you, too emotional? You are fascinated and fearful at the depth of his feelings.

You are not responsible for your child’s happiness, Rexi’s teacher in her fifties told you gently the other day.

‘All you’re responsible for is what is said and done to them, as a parent. That’s all. Nothing else.’ You must remember that.

Lesson 14

Herein the patient must minister to herself

Nine-thirty. You step outside. Lock the door.

Now you are in control. You inhale a breath of steely night air; the cold never ceases to shock in this place, after all these years, still. The children are all asleep, you know they will not wake, know them well enough. You stood in the quietness of their rooms and breathed them in deep and felt a vast peace flood through you, whispering a soothing through your veins. Everyone down, your day done.

But now.

Walking fast through a stillness that is holding its breath. Feeling an old you coming back. The stone walls, the close woods, the bridge over the stream are all coated in a thick frost that has not broken for several days and it is ravishingly beautiful, all of it, but it will never hold your heart. Because it is not home.

It is flinchingly cold, you are not dressed for it, have not thought, just needed to walk, get away, out. Hugh has a work dinner, he’ll be home in a couple of hours, you’ll be back for him, of course. It is suddenly overwhelming you as you walk, the tears are coming now. You dream of being unlocked. By spareness. Simplicity. Light, screaming hurting light. Dream of tall skies, endless space, of being nourished within the sunlight, of never coming back. The tears are streaming now, great gulps, your mouth is webbed by wet. You are not strong here.

You are on the road now, not properly dressed, cannot go back, cannot face any of it. A car flashes by, swerves, beeps in annoyance. There are no footpaths, only grass verges, the lanes are too narrow, built for carts centuries ago, you shouldn’t be walking in this place. You freeze in terror like a rabbit, can’t go forward, can’t go back. You hold your arms around you and weep, and weep, vined by circumstance – you are no longer you. Lost.

Lesson 15

We are able to pass out of our own small daily sphere

More headlights. A van.

Slowing, stopping. You shiver, your heart beats fast.

‘Hello, stranger.’

It is Mel. Another school mum. The one who is different, who never quite belongs. Who breezes in and out of the school like she couldn’t care less, who is … unbound. Who says fuck the quiz night, fuck the summer party, fuck the lot of it: I’ve got better things to do with my life. What, God knows.

She wears real, cool, vintage fur: I don’t do fake anything – coats, fingernails, orgasms.

Everyone suspects she’s been given the school fees for free, the charitable slot. She’s a single mum with a son in Jack’s class. You envy the every-second-weekend-off-from-motherhood that she gets – to sleep in, stay in bed all day, go dancing, potter, drink; to do nothing and everything for once. She runs an antique shop on the High Street – erratic opening hours, bric-a-brac from French flea markets – things you love that Hugh bats away as junk.

Mel picked up her boy, Otis, from a play date once, late. She’d come straight from her pole-dancing class and until that moment you’d had no idea such a thing existed in this place. Mel would have been the girl who wore her school skirt too short and had her dad’s ciggies in her pocket and smuggled dope into the dormitory; it’s all in her face. Appetite and passion and life’s hard knocks and a big open heart no matter how many times she’s pounded upon the rocks. An aura of a woman who revels in life. Who has sex a lot.

Mel always lingers after the boys’ occasional play dates. There’s often been some strange pull, in the silence, you don’t know why; you just want to lean across, it’s ridiculous, she’s not your type, your style. She wears skinny jeans, sometimes Uggs; your palette is the colour of reticence, careful camel or sand or chalk with a dash of black. She’s a woman for God’s sake.