Popular Music

Popular Music

Mikael Niemi

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

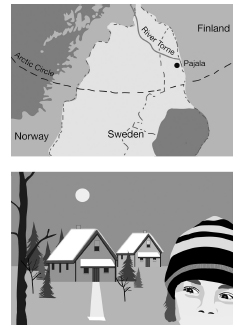

Maps

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Epilogue

Copyright

About the Publisher

Maps

Prologue

The narrator wakes up, starts on his climb and finds himself in a spot in the Thorong La Pass, whereupon the story can commence.

It was a freezing cold night in the cramped wooden hut. When my travel alarm started peeping I sat up with a start, unlaced the top of my sleeping bag and reached out into the pitch-black cold. My fingers groped around on the rough wooden floor, through all the splinters and grains of sand and the naked draught from the gaps in the floorboards until they found the cold plastic of the clock and the off-button.

I lay there motionless for a while, semi-conscious, clinging on to a log with one arm trailing in the sea. Silence. Cold. Short panting breaths in the thin air. Still lingering in my body was an ache, as if I’d spent the whole night with muscles tensed.

It was then, at that very moment, that I realised I was dead.

The experience was difficult to describe. It was as if my body had been emptied. I had been turned into stone, an incredibly big, bleak meteorite. Embedded deep down in a cavity was something strange, something long, thin and soft, organic. A corpse. It wasn’t mine. I was stone, I was merely embracing the body as it grew ever colder, encompassing it like a colossal, tightly closed granite sarcophagus.

It lasted two seconds, three at most.

Then I switched on my torch. The alarm clock display showed zero and zero. For one awful moment I had the feeling that time had ceased to exist, that it could no longer be measured. Then it dawned on me that I must have set the clock to zero when I was fumbling for the off-button. My wristwatch said twenty past four in the morning. All round the breathing hole of my sleeping bag was a thin layer of frost. The temperature was sub-zero, even though I was indoors. I braced myself against the cold, wriggled out of my sleeping bag, fully clothed, and forced my feet into my icy walking boots. Somewhat uneasily I packed my empty notebook into my rucksack. Nothing today either. No draft, not even a single note.

Up with the metal catch on the door and out into the night. The starry sky stretched away into infinity. A crescent moon was bobbing on the horizon like a rowing boat, and the jagged outlines of the Himalayan giants loomed dimly on all sides. The starlight was so strong that it drenched the ground – sharp, white spray from a colossal shower head. I manoeuvred into my rucksack, and even that little effort left me panting for breath. The lack of oxygen sent tiny spots dancing before my eyes. A rasping cough scraped through my throat, hacking bellows, 14,450 feet above sea level. I could just make out the path running steeply up the stony mountainside before disappearing into the darkness. Slowly, ever so slowly I started climbing.

The Thorong La Pass, Mount Annapurna in Nepal. 17,765 feet above sea level. I’ve conquered it. Up there at last! My relief is so great, I flop down on my back and lie gasping for breath. Lactic acid is making my leg muscles ache, my head is throbbing, I’m in the early stages of altitude sickness. Daylight is worryingly blotchy. A sudden gust of wind is a warning that nastier weather is on the way. The cold bites into my cheeks, and I can see a handful of hikers quickly shouldering their rucksacks and starting their descent to Muktinath.

I’m left all alone. Can’t bring myself to leave, not yet. I sit up, still gasping for breath. Lean back against the cairn with its fluttering Tibetan prayer flags. The pass is made up of stones, a sterile expanse of gravel with no vegetation at all. Mountain peaks loom up on all sides, rough black façades dotted with heavenly white glaciers.

Gusts of wind fling the first snowflakes into my anorak. Not good. If the path gets buried in snow, it can be dangerous. I look back over my shoulder: no sign of any other hikers. I’d better get back down quickly.

But not just yet. I’m standing at the highest point I’ve ever been in my life. Must bid it farewell first. Must thank somebody. A sudden urge takes possession of me, and I kneel down beside the cairn. Feel a bit silly, but another look round confirms that I’m on my own. I bend quickly forwards, like a Muslim with my backside in the air, lower my head and mumble a prayer of gratitude. I notice an iron plate engraved with Tibetan writing, a text I am unable to understand but one that exudes solemnity, spirituality, and I bend further down to kiss the text.

At that very moment a memory comes back to me. A vertiginous pit down into my childhood. A tube through time down which someone is shouting out a warning, but it’s too late.

I’m stuck fast.

My damp lips are frozen onto a Tibetan prayer plaque. And when I try to loosen my lips by wetting them with my tongue, that sticks fast as well.

Every single child from the far north of Sweden has no doubt found itself in the same plight. A freezing cold winter’s day, a railing, a lamp post, a piece of iron coated in hoar frost. My own memory is suddenly crystal clear. I’m five years old, and my lips are frozen onto the keyhole of our front door in Pajala. My first reaction one of vast astonishment. A keyhole that can be touched without more ado by a mitten or even a bare finger. But now it’s a devilish trap. I try to yell, but that’s not easy when your tongue is stuck fast to the metal. I struggle with my arms, trying to tear myself loose by force, but the pain forces me to give up. The cold makes my tongue numb, my mouth is filled with the taste of blood. I kick against the door in desperation, and emit an agonized:

‘Aaahhh, aaahhh…’

Then Mum appears. She’s carrying a bowl of warm water, she pours it over the keyhole and my lips thaw out and I’m freed. Bits of skin are still sticking to the metal, and I resolve never to do that ever again.

‘Aaahhh, aaahhh,’ I mumble as the snow starts lashing into me. Nobody can hear me. If there are any hikers on their way up, they’ll no doubt turn back now. My backside is sticking into the air, the wind is whipping up and making it colder by the minute. My mouth is starting to go numb. I pull off my gloves and try to warm myself loose with my hands, panting away with my hot breath. But it’s all in vain. The metal absorbs the heat but remains icy cold. I try to lift up the iron plaque, to wrench it loose, but it’s firmly anchored and doesn’t shift an inch. My back is covered in cold sweat. The wind worms its way inside my anorak lining and I start shivering. Low clouds are gathering and enveloping the pass in mist. Dangerous. Bloody dangerous. I’m getting more and more scared. I’m going to die here. I’ll never last out the night frozen onto a Tibetan prayer plaque.

There’s only one possibility left. I must wrench myself free.

The very thought makes me feel sick, but I have no choice. Just a little tug first, as a test. I can feel the pain right back to the root of my tongue. One…two…now…

Red. Blood. And pain so extreme I have to beat my head against the iron. It’s not possible. My mouth is stuck just as firmly as before. My whole face would fall apart if I tugged any harder.

A knife. If only I had a knife. I feel for my rucksack with my foot, but it’s several metres away. Fear is churning my stomach, my bladder feels about to burst. I open my zip and get ready to pee on all fours, like a cow.

Then I pause. Feel for the mug that’s hanging from my belt. Fill it full of pee, then pour the contents over my mouth. It trickles over my lips, starts the thawing process, and a few seconds later I’m free.

I’ve pissed myself free.

I stand up. My prayers are over. My tongue and lips are stiff and tender. But I can move them again. At last I can start my story.

Chapter 1

—in which Pajala enters the modern age, music comes into being and two little boys set out, travelling light

It was the beginning of the sixties when tarmacked roads came to our part of Pajala. I was five at the time and could hear the noise as they approached. A column of what looked like tanks came crawling past our house, digging and scratching at the potholed dirt road. It was early summer. Men in overalls marched around straddle-legged, spitting out wads of snuff, wielding crowbars and muttering away in Finnish while housewives peered out from behind the curtains. It was incredibly exciting for a little kid. I clung to the fence, peeping out through the rails, and breathed in the diesel fumes oozing out of those armoured monsters. They prodded and poked into the winding village road as if it were an old carcass. A mud road with lots and lots of holes that used to fill with rain, a pock-marked surface that turned butter-soft every spring when the thaw came, and in summer it was salted like a minced meat loaf to prevent dust flying around. The dirt road was old-fashioned. It belonged to a bygone age, the one our parents had been born into but were now determined to put behind them, once and for all.

Our district was known locally in Finnish as Vittu-lajänkkä, which means something like Cuntsmire. It’s not clear how the name originated, but it probably has to do with so many babies being born here. There were five children in some of the houses, sometimes even more, and the name became a sort of crude tribute to female fertility. Vittulajänkkä, or Vittula as it’s sometimes shortened to, was populated by poor villagers who grew up during the hardship years of the thirties. Thanks to hard work and a booming economy they worked their way up the ladder and managed to borrow money to buy a house of their own. Sweden was flourishing, the economy was expanding, and even Tornedalen in the far north was being swept along with the tide. Progress had been so astonishingly fast that people still felt poverty-stricken even though they were now rich. They occasionally worried that it might all be taken away from them again. Housewives trembled behind their home-made curtains whenever they thought about how well-off they were. A whole house for themselves and their offspring! They’d been able to afford new clothes, and the children didn’t need to wear hand-me-downs and patches. They’d even acquired a car. And now the dirt road was about to disappear, and be crowned with oily-black asphalt. Poverty would be clothed in a black leather jacket. What was being laid was the future, as smooth as a shaven cheek. Children would cycle along it on their new bikes, heading for welfare and a degree in engineering.

The bulldozers bellowed and roared. Gravel poured out of the heavy lorries. Enormous steamrollers compressed the hard core with such incomprehensible force that I wanted to stick my five-year-old foot underneath to test them. I threw big stones in front of a steamroller, then ran out to look for them when it had rumbled past, but there was no sign of the stones. They’d disappeared, pure magic. It was uncanny and fascinating. I lay my hand on the flattened-out surface. It felt strangely cold. How could coarse gravel become as smooth as a newly-pressed sheet? I threw out a fork taken from the kitchen drawer, and then my plastic spade, and both of them disappeared without trace. Even today I’m not sure whether they are still concealed there in the hard core, or if they did in fact dissolve in some magical way.

It was around this time that my elder sister bought her first record player. I sneaked into her room when she was away at school. It was on her desk, a piece of technical wizardry in black plastic, a shiny little box with a transparent lid concealing remarkable knobs and buttons. Scattered all round it were curlers, lipstick and aerosol cans. Everything was modern, unnecessary luxuries, a sign of our new riches heralding a future of waste and welfare. A lacquered box contained piles of film stars and cinema tickets. Sis collected them, and had fat bundles from Wilhelmsson’s cinema, each one with the name of the film, the leading actors and marks out of ten written on the back.

She’d placed the only single she owned on a plastic contraption looking like a plate rack. I’d been made to cross my heart and promise never even to breathe on it. Now, my fingers tingling, I picked it up and stroked the shiny cover depicting a handsome young man playing a guitar. He had a dark lock of hair dangling down over his forehead, and was smiling straight at me. Ever so painstakingly I slid out the black vinyl. I carefully lifted the lid of the record player. Tried to remember how sis had done it, and lowered the record onto the turntable. Fitted the hole of the EP over the central pin. And so full of expectation that I’d broken out into a sweat, I switched on.

The turntable gave a little jerk, then started spinning. The tension was unbearable, I repressed the urge to run away. With my awkward, stumpy boy’s fingers I took hold of the snake, the rigid black pick-up arm with its poisonous fang, as big as a toothpick. Then I lowered it onto the spinning plastic.

There was a crackling, like pork frying. I just knew something had broken. I’d ruined the record, it would be impossible to play it ever again.

BAM-BAM…BAM-BAM…

No, here it came! Brash chords! And then Elvis’s frantic voice.

I was petrified. Forgot to swallow, didn’t notice I was slavering. I felt dizzy, my head was spinning, I forgot to breathe.

This was the future. This was what it sounded like. Music like the bellowing of the road-building machines, a never-ending clatter, a commotion that roared away towards the crimson sunrise on the far horizon.

I leaned forward and looked out of the window. Smoke was rising from a tipper lorry, they were starting the final surfacing. But what the lorry was spewing forth was not black, shiny-leather asphalt. It was oil-bound gravel. Grey, lumpy, ugly, bloody oil-bound gravel.

That was the surface on which we inhabitants of Pajala would be cycling into the future.

When all the machines had finally gone away I started going for cautious little walks round about the neighbourhood. The world grew with every step I took. The newly surfaced road led to other newly surfaced roads, the gardens stretched away like leafy parks with giant dogs standing guard, barking at me and rattling their running chains. The further I walked, the more there was to see. The world never seemed to end, it just went on and on, and I felt so dizzy I was almost sick when it dawned on me that you could go on walking for ever. In the end I picked up courage and went over to Dad, who was busy washing our new Volvo PV:

‘How big is the world?’

‘It’s enormous,’ he said.

‘But it must stop somewhere, surely?’

‘In China.’

That was a straightforward answer that made me feel a bit better. If you walked far enough, you’d eventually come to an end. And that end was in the realm of the slitty-eyed ching-chong people on the other side of the globe.

It was summer and roasting hot. The front of my shirt was stained by drops from the ice-lolly I was licking. I left our garden, left my safe little world. I occasionally looked back over my shoulder, worried about getting lost.

I walked as far as the playground which was really an old hayfield that had survived in the middle of the village. The local authority had installed some swings, and I sat down on the narrow seat. Started heaving enthusiastically on the chains in order to build up speed.

The next moment I realised I was being watched. There was a boy sitting on the slide. Right up at the top, as if he were about to come down. But he was waiting, as motionless as a hawk, watching me with wide-open eyes.

I was on my guard. There was something worrying about the boy. He can’t have been sitting up there when I arrived, it was as if he’d materialised out of thin air. I tried to ignore him, and drove the swing up so dizzyingly high that the chains started to feel slack in my hands. I made no sound and closed my eyes, and could feel my stomach churning as I hurtled down in a curve faster and faster towards the ground, then up towards the sky on the other side.

When I opened my eyes again he was sitting in the sandpit. As if he’d flown there on outstretched wings: I hadn’t heard a thing. He was still watching me intently, although he was half-turned away from me.

I allowed the swing to come slowly to a stop, and in the end I jumped down onto the grass, did a forward roll and remained lying there on the ground. Stared up at the sky. Clouds were rolling over the river in patches of white. They were like big, woolly sheep lying asleep in the wind. When I closed my eyes I could see little creatures scuttling about on the inside of my eyelids. Small black dots creeping over a red membrane. When I shut my eyes tighter I could see little violet-coloured fellows in my stomach. They clambered over one another and traced patterns. So there were animals inside me as well, a whole new world to explore in there. I felt giddy as it dawned on me that the world was made up of masses of pockets, each of them enclosing the previous one. No matter how many layers you penetrated, there were more and more still to come.

I opened my eyes and gave a start. I was astonished to see the lad lying beside me. He was stretched out on his back right next to me, so close that I could feel the warmth of his body. His face was strangely small. His head was normal, but his features had been crammed into far too small a space. Like a doll’s face glued onto a large, brown, leather football. His hair had been clipped unevenly at home, and a scab was working its way loose on his forehead. His face was turned towards me. He was screwing up one eye, the upper one that was catching the sun. The other was lying in the grass and wide open, with an enormous pupil in which I could see my own reflection.

‘What’s your name?’ I wondered.

He didn’t answer. Didn’t move.

‘Mikas sinun nimi on?’ I repeated the question in Finnish.

Now he opened his mouth. It wasn’t a smile, but you could see his teeth. They were yellow, coated with bits of old food. He stuck his little finger into his nostril – the others were too big to fit in. I did the same. We each dug out a bogey. He stuck his into his mouth and swallowed. I hesitated. Quick as a flash he scraped mine off my finger and swallowed that as well.

I realised he wanted to be my friend.

We sat up in the grass, and I had an urge to impress him in return.

‘You can go wherever you like, you know!’

He was listening attentively, but I wasn’t sure if he’d understood.

‘Even as far as China,’ I added.

To show that I was serious I started walking towards the road. Confidently, with an affected, pompous air of self-assurance that concealed my nervousness. He followed me. We walked as far as the yellow-painted vicarage. There was a bus parked on the road outside, no doubt it had brought some tourists to see the Laestadius House which was just a few doors away. We bowed our heads in acknowledgement of the Bible-thumping evangelist who once lived there. The bus doors had been left open because of the heat, but there was no sign of the driver. I grabbed the lad and pulled him over to the steps, and we climbed aboard. There were suitcases and jackets lying on the seats, which smelt a bit damp. We sat right at the back and crouched down behind the back of the seats in front. Before long some old ladies got in and sat down, panting and sweating. They were speaking a language with a lot of waterfall sounds, and gulping down big swigs of lemonade straight from the bottle. Several more pensioners eventually came to join them, and then the driver turned up, paused outside to insert a wad of snuff into his mouth. Then we set off.

Wide-eyed and silent, we watched the countryside flash past. We soon left Pajala behind and breezed off into the wilds. Nothing but trees, trees without end. Old-fashioned telephone poles with porcelain insulators and wires sagging in the heat.

We’d gone several kilometres before anybody noticed us. I happened to bump against the seat in front, and a lady with pincushion cheeks turned round. I smiled expectantly. She smiled back, rummaged around in her handbag and then offered us a sweet from an unusual cloth-like bag. She said something I didn’t understand. Then she pointed at the driver and asked:

‘Papa?’

I nodded, my smile frozen.

‘Habt ihr Hunger?’ she asked.

Before we knew where we were she’d thrust a cheese roll into each of our hands.

After a long and shaky bus ride we pulled up in a large car park. Everybody got off, including me and my friend. In front of us was a big concrete building with a flat roof and high, spiky, metal aerials. Beyond it, behind a wire fence, were some propeller-driven aeroplanes. The bus driver opened a hatch and started pulling out bags and suitcases. The nice lady had far too much luggage and seemed to be under a lot of strain. Beads of sweat were forming under the brim of her hat, and she started making nasty smacking noises, sucking at her teeth. My friend and I gave her a hand as a way of saying thank you for the sandwiches, and we lugged her heavy case into the building. The flock of pensioners crowded round a desk, jabbering away loudly, and started to produce no end of papers and documents. A woman in uniform tried patiently to keep them in order. Then we passed through the gate as a group and made our way towards the aircraft.

It was going to be my first ever flight. We both felt a bit like fish out of water, but a nice, brown-eyed lady with gold heart-shaped earrings helped us to fasten our seatbelts. My friend landed up in a window seat, and we grew increasingly excited as we watched the shiny propellers start spinning round, faster and faster, until they disappeared altogether in a round, invisible whirl.

Then we started moving. I was forced back into my seat, could feel the wheels bumping, and then the slight jerk as we left the ground. My friend was pointing out of the window, fascinated. We were flying! There was the world down below us. People, buildings, and cars shrunk to the size of toys, so small we could have popped them into our pockets. And then we were swallowed up by clouds, white on the outside but grey inside, like porridge. We emerged from the clouds and kept on climbing until the aircraft reached the sky’s roof and started soaring forwards so slowly we hardly knew we were moving.

The nice air hostess brought us some juice, which was just as well as we were very thirsty. And when we needed a pee she ushered us into a tiny little room and we took it in turns to get our willies out. We peed into a hole, and I imagined it falling right down to the ground like a yellow drizzle.