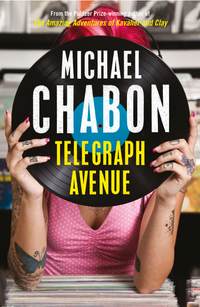

Telegraph Avenue

“Way too much,” Archy agreed.

“Swear to me, Archy,” she said. “Raise your right hand and swear to me, on the soul of your mother, you aren’t getting up to anything with that girl, Chewbacca or whatever her name is.”

“I swear,” Archy said, but there was appended no oath that might require the damnation of his late mother. No raised hand.

“Raise it up,” Gwen said.

Archy lifted his right hand, a flag of surrender.

“Swear. On the soul of your mother, who raised you to be a better man than that.”

Before forming the words required, Archy hesitated, and in that half-second he was lost. All Gwen’s protestations of dignity and invocations of self-respect were scattered like deck chairs on the promenade of a heaving ship. She glanced up and down the street, casing it for witnesses, then plunged her hand down into the front of his pants. The upper serif of his belt buckle, a gold Ferragamo F, scraped her wrist. Her fingers found the heavy coil of hose cupped in the bag of his boxers. Her fingertips were briefly snagged by a film of bodily adhesive as weak as the glue on a Post-it. She tugged her sticky fingers loose, brought them to her nose, and took a quick but practiced sniff. Market stalls, smoking braziers, panniers of lentils. All the spice and stink of Ethiopia: turmeric, scorched butter, the salt of the Red Sea.

“Motherfucker,” Gwen said, turning on itself, like a cell going cancerous, the oath that Archy would not swear. It was only the third time in her life that she had used the word, and the first time without quotation marks demurely implied, and after it there was nothing more to say. Gwen went around to the driver’s side of the car, ignoring a parking citation in an acid-green envelope that had been poked, during her absence, under her left wiper. She guided herself into the space between seat and steering wheel. Then she and her battered dignity drove off, with the parking ticket flapping against the windshield and with the want of a cup of suff—for one more caramel sip of which she just then would have endured any affront to her self-esteem or stain upon her pride—doomed to burn on inside her, unassuaged, for many days.

The house on Stonewall Road was one of those California canyon houses put up in the late sixties with a Jet Propulsion Laboratory arrogance toward gravity, a set of angles on skinny poles engineered out into the green void. From the street, all you could see of it was its mailbox and carport, with the house concealed downslope as if it planned to spring an ambush on a passerby. In the middle of the driveway, over an eternal attendant puddle of leaking motor oil, sat Aviva Roth-Jaffe’s car, a Volvo station wagon whose age could be reckoned in decades. It had gold-on-blue vanity plates that read HEK8. At some point it had been condemned by a hundred-dollar Earl Scheib paint job to approximate the color of a squirt of fluoride Crest.

Gwen leaned against the trunk of her car, took a long slow breath. Shook off as much of the memory of the past half hour as would shake loose, and tamped down everything else. She had work to do, and when this job was over, her husband would still be there, and he would still be a dog, and the smell of another woman’s pussy would still be on him. She hoisted her black gym bag over her shoulder—the bag held clean bed linens, gloves, meds and syringes, forceps, a portable Doppler—and hefted it and herself down the twisting stairway from the street to the front door. The slope behind her was overgrown with morning glory. Tendrils of jasmine fingered the wooden stairs. A huge trumpet vine with its disappointed yellow mouths threatened to engulf the wooden house clear to the peak of the steep shed roof. The air on Stonewall Road smelled of cedar bark, eucalyptus, fir logs burning in a woodstove. From the lowest limb of a Meyer lemon, a wind chime searched without urgency for a melody to play. An adhesive sticker pasted to the sidelight beside the front door told prospective firefighters how many cats (three) to risk their lives in rescuing. From inside the house came the forlorn and piteous bellowing of an animal in pain.

“Hello?” Gwen called, letting herself in the front door. A small black Buddha greeted her from a low table by the front door, where it kept company with a photograph of Lydia Frankenthaler, the producer of an Oscar-winning documentary film about the neglected plight of lesbians in Nazi Germany; Lydia’s partner, Garth; and Lydia’s daughter from her first marriage, a child whose father was black and whose name Gwen had forgotten. It was a Chinese Buddha, the kind that was supposed to pull in money and luck, jolly, baby-faced, and potbellied, reminding Gwen of her darling husband apart from the signal difference that you could rub the continental expanse of Archy Stallings’s abdomen for a very long time without attracting any flow of money in your direction. “Somebody having a baby around here?”

“In here, Gwen,” Aviva said.

Lydia and Garth, a lawyer for the poor, were having their baby in their living room. It was a large room with a vaulted ceiling and nothing between it and the canyon but a wall of solid glass. The girl—Arabia, Alabama, she had a geographical name—sat marveling blankly at the spectacle of her naked mother reposed like an abstract chunk of marble sculpture in the center of the room. Against her legs the girl held a rectangle of cardstock to which she had pasted the three pages of her mother’s birth plan, decorating the borders in four colors of marker with flowers and vines and a happy-looking fetus labeled BELLA. Two low sofas had been pushed to the sides of the room to make space for a wide flat sandwich crafted from a tatami mat, a slab of egg-carton foam rubber, and a shower curtain decorated with a giant self-portrait of Frida Kahlo. Garth, a small-boned, thin-shanked man with a red beard and red stubble on his head, lay sleeping on the improvised bed.

“I’m at nine!” said Lydia by way of greeting, adding whatever comment was provided by her spread, furry-ish butt cheeks and the backs of her legs as she bent over in the downward-facing-dog position to grab two handfuls of floor. “A hundred percent effaced.”

“I’ve been trying to persuade her to try a little push,” said Aviva. She tilted back on her haunches, down on the floor beside Lydia, studying the looming pale elderly secundigravida. Disapproving of the woman, but only Gwen would have caught it, the lips pursed to the left as if withholding a kiss. Barefoot in a loose cotton shift over black ripstop pedal pushers, the roiling surf of her black hair, with its silver eddies, pulled back and tied in a sloppy bun. Stubble showing blue against her luminous shins. Toenails painted a deep cocoa red like the skin of Archy’s Queen of Sheba. “But all Mom wants to do is goof around like that.”

“I don’t want to push,” Lydia said. A string of pain drew and cinched her voice, a yogic voice, inverted and tied carefully to the rhythm of her breathing. “Is it okay, Gwen? Can’t I just stay this way for a little while longer? It feels a lot better.”

If Aviva said it was time to try a little push, then it was, in Gwen’s view, time to try a little push. You did not get to be the Alice Waters of Midwives by leaving your gratins in the oven too long.

“Well, you’ve got gravity working for you,” Gwen tried, less inclined than her partner to patience or politeness but good for at least one go-round with an upside-down naked lady in labor. “But if anybody ever pushed out a baby in that jackknife thing you’ve got working right there, Lydia, then I never heard about it.”

“It could be interesting,” Aviva said. “Now that you mention it. Maybe you should give it a try.” The words were humorous, but her tone continued to be critical, at least to Gwen’s ear.

“Let me just wash my hands and whatnot, and then I’ll fire up my Doppler and see what’s happening in there,” Gwen said, dropping her bag on a black leather armchair. “Hi, honey.” Arcadia. “What do you think of all this, Miss Arcadia?”

The girl shrugged, eyes wide and teary but not despairing. Without cant or reference to the threefold moon goddess or other such nonsense, it was a deep and solemn business that they were about in this room, and nobody was going to feel that, in all its fathomlessness, like a kid. Certainly not old Garth over there, sacked out with one toe poking out of his left sock and sleep working the bellows of his skinny frame.

“Kind of gross,” the girl said, hoisting the birth plan higher as if to shield herself from the grossness of it. Article Seven requested that the umbilical cord not be cut until the placenta had ceased to pump. Article Twelve was some kind of nonsense about the use of artificial light. Gwen was not one to disrespect a well-made birth plan, but there were always wishful thinking and juju involved, and when things went the way they were going to go, as they must, many plans took on a retrospective air of foolishness. “No offense, Mom.”

“You don’t.” The string cinching tighter. “Have to. Watch it, baby. I told you—”

“I want to stay.”

“Gross can be interesting,” Gwen said. “Huh?”

Arcadia nodded.

Lydia lowered her hips and sank to her knees, giving way like a sand castle, and on all fours she rested, head hung, eyes closed, as if about to pantomime some animal behavior. “I’m going to push now,” she announced. In the same stewardessy voice, she added, “Everyone please shut up.”

Her tone was wrong and startling, like a struck wineglass with a secret flaw, and at once Garth sat up and gaped at Gwen, blinking, wiping his lips with his sleeve. “What’s wrong?” he said. His eyes came unstuck from Gwen’s, and he looked around, kicking up from the deep-sea trench of a dream, looking for his new baby, finding his wife, who was seeing nothing at all.

“Everything’s fine, sweetie,” Aviva said. “Only we’re going to need Frida Kahlo.”

Gwen went into the kitchen to drink a glass of water and, in the name of asepsis if not pride, eradicate every last whiff of Elsabet Getachew from her hands. No excuse for you—that was sterling dialogue. She strangled the renascent memory of her shame with a pair of latex-free gloves. When she came back into the living room, she saw that Frida Kahlo had been veiled with an orange bath towel. Lydia lay on her back, propped up on an old plaid bolster, pale abdomen shot like an eyeball with capillaries, making a new kind of low growling sound that built slowly to an energetic whoop and flowered in a burst of foul language that made everybody laugh.

“Good one,” Aviva said. “Good one.”

Though Aviva had caught a thousand babies with hands that were steady and adept, now that it was time, she deferred to her partner, to the virtuoso hands of Gwen Shanks, freaky-big, fluid as a couple of tide-pool dwellers, cabled like the Golden Gate Bridge.

As Aviva gave way to Gwen, she tried by means of her powerfully signifying eyebrows to communicate that she felt something in this situation to be amiss, something not provided for in the birth plan, which lay sagging and looped onto itself under the little girl’s chair. Aviva’s apparent psychic ability to know in advance when something might go wrong, especially in the context of a birth, was not merely the statistical fruit of an abiding pessimism. Skeptic that she was, Gwen had seen Aviva make unlikely but correct predictions of disaster too many times to discount. Gwen frowned, trying to see or feel what Aviva had detected, coming up short. By the time she turned to Lydia, every trace of the frown had been blown away.

“Okay,” she said, “let’s see what little old Miss Bella is up to.”

Gwen lowered herself by inches and prayers to the floor and, when she arrived, saw that the inner labia of Lydia Frankenthaler had conformed themselves into a fiery circle. A smear of fluid and hair presented its credentials at this checkpoint, advance man for the imminently arriving ambassadress from afar.

“You’re working fast now,” Gwen said. “You’re crowning. Here we go. Oh my goodness.”

“Lydia, honey, remember how you said you really didn’t want to push,” Aviva said, climbing in alongside Gwen, “well, now I would actually like you to stop. Stop pushing. Just let her—”

“Coming fast,” Gwen said. “Look out.”

There was a ripple of liquid and skin, then with a vaginal sigh, the little girl squirted faceup into Gwen’s wide hands. The small eyes were open, nebular, and dull, but in the instant before she cried out, they ignited, and the child seemed to regard Gwen Shanks. The air was filled with a hot smell between sex and butchery. The father said “oh” and pressed in beside Gwen to take the sticky baby as she passed it to him. Arcadia hung back, aghast and thrilling to the redness of the birth and the life kindling in her father’s hands. They wrapped the baby loosely in a candy-striped blanket, and as Aviva stroked Lydia’s hair and helped to raise her head, Garth and Arcadia made the necessary introductions of mother and baby and breast. That left Gwen, crouched at the other end of the silvery umbilicus, to observe the heavy flow of blood that seeped from Lydia’s vagina in a slow pulsation, like water from a saturated sponge.

It required all of Gwen’s training and innate gift for minimization of disaster not to pronounce the fatal syllables “Ho, shit.” But Aviva caught something in her face or shoulders, and when Gwen looked up from the pulsing blood that had begun to pool in a red half-dollar on the shower curtain, her partner was already on her way around to have a look. Aviva hunched down behind Gwen, an umpire leaning in on a catcher’s shoulder to get a better look at the ball as it came down the pike. She smelled of lemon peel and armpit in a way that barely registered with Gwen by now except as a steadying presence. They settled in to wait for the placenta. The soft click-click of the baby’s nursing marked the passing of several minutes. Aviva reached down and gave a gentle tug on the umbilical cord. She frowned. She made a humming sound deep in her throat and then said, “Hmm.”

Her tone pierced the bubble of family happiness up by Lydia’s head. Garth looked up sharply. “Is it all right?”

“It’s fine.”

Gwen ripped back the Velcro straps of her hypodermic kit, unrolled it, and felt around with her left hand for the vial of Pitocin.

“Right now,” Aviva said, “the placenta is feeling a little shy, so we just all want to really encourage the uterus to do some contracting for us. Lydia, you just keep right on nursing her, that’s the very best thing you can do. How’s that coming?”

“She went right on!” Lydia cried. Everything was wonderful in the world where she had taken up residence. “Great latch. Sucking away.”

“Good,” Gwen said, practicing the business of syringe and vial in a mindful series of ritual taps, sinking the vial onto the shaft of the needle, reading the tale of liquid and graduation. “Keep it up. And just to make sure it all gets nice and tight and contracted in there, we’re going to give you a little Pitocin.”

“What’s the deal?” said Garth. He craned forward to see what was happening between his wife’s legs. There was not, say, an ocean of blood, but there was more than enough to shock an innocent new father awash in a postpartum hormonal bath of trust in the world’s goodness. “Oh, goddammit. Did you guys fuck something up?”

He swore stiffly but with a sincere fury that took Gwen by surprise. She had pegged him as the gently feckless type of Berkeley white guy, drawstring pants and Teva sandals worn over hiking socks, sworn to a life of uxorial supportiveness the way some monks were sworn to the work of silence. Gwen didn’t know that Garth and Lydia had quarreled repeatedly over the idea of home birth, that Garth had viewed Lydia’s insistence on having their baby at home as the latest in a string of reckless and unnecessarily showy acts of counterconventionality that included refusing, to date, three separate proposals of marriage from Garth. Garth believed in hospitals and vaccines and government-sanctioned monogamy and had absorbed from his poor black and Latino clients powerful notions of the sovereignty of bad luck and death. He had suffered no ill fortune throughout the length of a tranquil, comfortable, and fulfilling life and so at any moment anticipated—even felt that he deserved—the swift equalizing backhand of universal misfortune.

“It’s okay, Dad,” Gwen said. “It’s going to be okay.”

“Yeah?”

“Oh, yeah.” She laid it on, but only because she could do so in good conscience. This kind of hemorrhaging was not unusual; the Pitocin would kick in momentarily, the uterus would contract, the mysterious bundle of the placenta, that doomed and transient organ, would complete its brief sojourn, and that would be that.

“I mean, well,” Garth said. He appeared to consider and decide against speaking the words that had entered his mind, so as not to cause alarm, then said them anyway: “It’s just that it looks kind of bad.”

Gwen’s eyes snapped onto the little girl, but Arcadia seemed to have decided not to know anything except the baby sucking at her mother’s left breast and the feel of her mother’s hand in hers.

“That’s mostly just lochia,” Gwen said. “Lining, mucus, all that good stuff. It’s normal.”

“Mostly,” Garth repeated, his tone both flat and accusatory.

“How about you run get us some towels, Dad,” Aviva suggested. “And lots of them.”

“Towels,” Garth repeated, clinging to the rope of his desire to be useful.

“Definitely,” Gwen said. “Go on, honey. Go on and get us like every damn towel you got. Also, yeah, some sanitary pads.”

Gwen had a more than adequate supply of pads in her bag, but she wanted to give him a concrete mystery to grow entangled in, hoping that might keep him busy for a few minutes. Whenever she asked Archy to bring her a Tampax, he always got this look on his face, somewhere between intimidation, as by an advanced concept of cosmic theory, and dread, as if mere contact with a tampon might cause him spontaneously to grow a vagina.

Garth went away muttering, “Towels and sanitary pads.”

Aviva called Aryeh Bernstein. “Sorry to bother you,” she said. She gave him the essentials, then listened to what their backup OB had to say about Lydia Frankenthaler’s placenta. “We did. Yep. Okay. All right, thanks, Aryeh. I hope I won’t have to.”

“What did he say?”

“He said more Pitocin and massage.”

“On it,” Gwen said.

As Aviva prepped another push, Gwen laid her hands on Lydia’s belly and felt, blindly and surely, for the hard shuddering uterus. She sank her fingers into the crepey flesh of Lydia’s abdomen and kneaded with dispassion and no more tenderness than a baker. She disbelieved in the mystical power of visualization according to strictures of her 97 percent rule, but that did not prevent her from imagining with every flexion of her fingers that Lydia’s womb was clenching, sealing itself up, condensing like a lump of coal in Superman’s fist to a hard bright healthy diamond.

They heard cabinets slamming in a bathroom somewhere with a panicked air of comedy, and then a glass broke, and the girl jumped. It was not impossible that Gwen jumped, too. Aviva held steady, guiding the second needle into Lydia’s vein.

“Hey, there, Arcadia,” Gwen said. “How you doing?”

“Good.”

“You got a nice strong grip on your mom’s hand, there?” The girl nodded, slow and watchful. Gwen winced at the false tone of cheeriness she could hear creeping into her voice. “Know what I’m doing? I’m massaging your mom’s uterus. Now, I know you know what a uterus is.”

“Yes.”

“Duh. Of course you do, smart as you are.”

“Oh, uh, Gwen, um,” Lydia said, and she sank back deeper against the plaid bolster, her head lolling like a flower on a broken stem. Her left arm with the baby curled in its crook subsided, and there was a loud smack as the small mouth popped loose. “Oh, man, you guys, I don’t know.”

“Any change?” Aviva said.

“Some.”

Gwen tried not to look at her partner as Aviva went over to her flight bag, a gaudy pleather thing blazoned with the obscurely ironic legend SULACO, and broke out the bags, barbs, and tubing of an IV kit. Gwen crouched, up to her elbows in the dough of the woman’s life, knowing that everything was going to be all right, that it was a matter of hormones and massage and a husband judiciously sent to find Kotex and bath towels. She also knew that she suffered from or had been blessed with a kind of reverse clairvoyance, the natural counterpart to her partner’s predictive pessimism. Gwen was resistant to if not proof against clear signs of danger or failure. Not because she was an optimist (not at all) but because she took failure, any failure, whether her own or the universe’s, so personally. If a bridge gave way outside of Bangalore, India, and a bus full of children plunged to their deaths, Gwen felt an atom-sized but detectable blip of culpability. She had been taught firmly that you could not take credit for success if you were unprepared to accept blame for failure, and one useful expedient she had evolved over the years for avoiding having to do the latter was to refuse—not consciously so much as through a reflexive stubbornness—to acknowledge even the possibility of failure. And that was what she would have to accept if she looked up from her wildly bread-making hands and saw Aviva, with that grim measuring gaze of hers, holding up the bag of intravenous saline to catch the sunshine, her mouth drawn into a thin defeated line.

“Don’t fall asleep, Mommy,” Arcadia said. “Here comes Daddy with the towels.”

Gwen hurried along the corridor, bleeding from a fresh cut on her left cheek, trussing her belly with one arm, trying to keep up with Aviva, who was trying to keep up with the single-masted gurney on which Lydia Frankenthaler was being sailed toward one of the emergency-room ORs by a crew of two nurses and the EMT who had accidentally slammed the ambulance door on Gwen’s face. The EMT hit the doors ass-first and banged on through, and the nurse who was not steering the IV pole turned and faced down the midwives as the doors swung shut behind her. She was about Gwen’s age, mid-thirties, a skinny ash-eyed blonde with her hair in a rubber-band ponytail, wearing scrubs patterned with the logo of the Oakland A’s. “I’m really sorry,” she said. She looked very faintly sorry. “You’ll have to wait out here.”

This was a sentence being passed on them, a condemnation and a banishment, but at first Aviva seemed not to catch on, or rather, she pretended not to catch on. As the Alice Waters of Midwives, she had been contending successfully and in frustration with hospitals for a long time, and though, by nature, she was one of the most candid and forthright people Gwen had ever known, if you sent her into battle with another nurse, an intake clerk, or most of all an OB, she revealed herself to be skilled in every manner of wheedlings and wiles. It was a skill that was called upon to one degree or another almost every time they went up against hospitals and insurance companies, and Gwen relied upon and was grateful to Aviva for shouldering the politics of the job so ably. She envied the way it seemed to cost Aviva nothing to eat shit, kiss up, make nice. Catching babies was the only thing Aviva cared about, and she would surrender anything except her spotless record for catching them safe and sound. She had, Gwen felt, that luxury.

“No, no, of course, we’ll wait,” Aviva said in a chipper voice. She made a great show of gazing down at herself, at her white shirt with its chart of blood islands, at the chipped polish on her big toenail. With the same partly feigned air of disapproval, she surveyed Gwen’s cheek, her played-out saggy-kneed CP Shades. Then Aviva nodded, granting with a smile the whole vibe of dirt and disorder that the partners were giving off. “But after we clean up and scrub in, right? then it’s no problem, right”—leaning in to read the nurse’s badge—“Kirsten? If you want to check with Dr. Bernstein, I’m sure . . .”

Gwen could see the nurse trying to determine whose responsibility it was in this situation to be the Asshole, which was of course the purpose of Aviva’s gambit. Sometimes that awful responsibility turned out to be endlessly deferrable, and other times you got lucky and ended up in the hands of someone too tired or busy to give a damn.