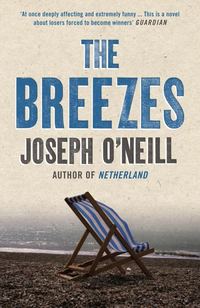

The Breezes

I could not blame him for reacting in this way. Not only had he sunk thousands into my education and training, he had sunk a pile of hope down there, too. My father had been banking on my accountancy career in every way. Thus, for a couple of months, he sought to induce and cajole and beg me to change my mind. One day I had just got out of the bath and was running shivering to my bedroom with a towel around my waist when he approached me in the corridor and said, ‘Son, I think it’s time we talked about where you are going with your life.’

I kept on running. ‘Pa, I’ve just got out of the bath, OK?’

But Pa was not to be put off and he followed me into my bedroom and addressed me while I towelled my hair and dried my toes and looked for socks. ‘Johnny,’ he said, ‘what do you want from your life? What are your goals?’

I turned from the cupboard to answer but I did not get any further than opening my mouth, because right in front of me my father was holding up a large home-made cardboard lollipop, and on it was written, in arresting black letters, GOALS.

I started laughing.

‘Son,’ Pa said, ‘think about it. You’re a man now. What are you aiming for?’ He put down the lollipop and brandished another: MONEY. ‘Is this what you want? Do you want money?’ He pulled out another: FAMILY WITH HOUSE, SECURITY. ‘A family, a house?’ JOB SATISFACTION, the next placard said. ‘How about job satisfaction?’ Pa said. ‘How important is that to you?’ He pointed at my feet. ‘Are you really going to wear those socks together? Look, they don’t even match.’

‘Don’t worry,’ I said, forcing my damp thighs into some jeans, ‘I’m not going out today.’

Pa was about to reply when he remembered the original point of the conversation. With an effort, he raised the three lollipops in his right fist, displaying them in a crooked fan, and then with his left hand he pulled a final lollipop from behind his back: in red letters, EVALUATION AND CHOICE. He stood there for a moment, arms aloft, like a man trying to wave in a wayward aeroplane. ‘You’ve got to work out which of these—’ he shook his right hand – ‘you want, and why, because I’m telling you now – and believe me, Johnny, I know what I’m talking about, I’ve been in this world a little longer than you have, listen to what I’m saying to you – I’m telling you that in this line of work you’ve taken up, you can forget about this—’ He dropped the MONEY lollipop on the floor. ‘And without money, it becomes very hard to have this—’ JOB SATISFACTION fell to the ground. ‘And this—’ Down with a clatter went the surviving sign, FAMILY WITH HOUSE, SECURITY. ‘Take it from me, Johnny, you’re running a big, big risk with this – this project of yours.’ He wiped sweat from his mouth and waited for me to respond. He had planned this presentation down to the last detail, that was obvious. I envisaged him with his glue and scissors and felt-tips, anxiously cutting circles in the cardboard, rehearsing his speech. Now the decisive moment had arrived: was I going to buy?

To stop Pa from seeing the laugh on my face, I pulled a jumper over my head and pretended to get caught up in the neckhole. ‘OK, Pa,’ I said, muffling my voice. ‘I’ll think about it. Thanks very much. I’ll get back to you,’ I said, still faking a struggle with my jumper.

‘I’m glad,’ Pa said, his voice trembling a little. ‘You think about it. Remember, don’t hesitate to come to me with any problems or ideas, or feedback generally. My door is always open,’ Pa said.

I am not sure which door my father was referring to when he said that, but of course I never took up his invitation. My mind was made up, and soon after what Pa liked to call our ‘meeting’ (‘Son, have you thought about our meeting? Have you got anything you want to tell me?’), I threw the lollipops into the bin in my bedroom, where they protruded from the yoghurt cartons and the tangerine peel and the other trash. Pa got the message.

Shortly after that, he approached me with his hands in his pockets. I knew what that meant; it meant that he was about to apologize. Whenever Pa is about to say he is sorry, his hands disappear into his trousers.

‘Listen, Johnny, I hope I haven’t upset you with what I said about your new line of work. I’m sorry if I have.’

‘No, Pa, of course you haven’t, I said.

He said, ‘I just want you to know that I’m on your side, son. I’m right behind you. You do what you want to do. What’s important is that you’re happy. As long as you’re happy, that’s all that counts.’ In his emotion he left the room and went to the kitchen and put his head into the fridge, pretending to look for something to eat.

What was it, then, that had blown Pa off course like this?

Chairs. That was all. I had decided to make a living making chairs.

‘You know, I’ve been thinking about it,’ he said when he returned from the kitchen. ‘Maybe it’s not such a bad idea.’ He started trying to light his pipe, the bowl of which was carved into the wise and unblinking visage of an ancient philosopher. At that time, Pa was going through a phase of pipe-smoking. ‘There’s a good market for chairs. People are always going to need to sit down. Let’s work it out.’ He took a company biro from the row of pens snagged on his breast pocket and flipped open a company scratch pad. ‘I’d say that people sit down now more than they ever did. I read about it somewhere – nowadays people are sitting down a whole lot more than they used to.’ Pa winked at me with his good eye. ‘Which means they’re going to need more chairs than ever before.’ He breathed on the nib of his biro, then slowly wrote down in capitals – Pa always writes in capitals – MORE CHAIRS THAN EVER BEFORE. ‘Yes,’ he said, growing excited, ‘and when you consider that more people are getting older now and that old people are always sitting down …’ INCREASED DEMAND, Pa wrote.

That clinched it for him. He threw down the biro with a bold finality. ‘Increased demand, Johnny. That’s what it’s all about. They demand, you supply. That’s the golden rule.’ He stood up, waving his pipe. ‘You know, I think you may be on to something. I think you may be on to something big.’

I said carefully, ‘I’m not sure how commercial I’m going to be, Pa.’

Pa was sucking away at his pipe, having another attempt at lighting it. ‘You may not be sure, son, but I am,’ he said, inhaling noisily. The philosopher’s cranium released a small cloud. ‘I see great possibilities in what you’re doing. Which is why I’ve come to a decision. I’m going to invest in you.’

‘Invest?’

‘That’s right. I’m going to set you up. I’m going to get you a proper workplace with proper equipment. No more scratching around in your bedroom upstairs.’

I stood up in protest. ‘There’s no need,’ I said. ‘I’m managing fine as it is. Pa, don’t even think about it,’ I said.

‘This isn’t a hand-out, this is business. You’ll pay me back with interest once you get going.’ He turned towards me with his skewy eyes wide open. ‘Johnny, we’re going to be partners!’

Looking back at that episode, at my unqualmish acceptance of finance, I cannot avoid a feeling of shame. In those days I found my father’s donations a marvellously uncomplicated business. I needed the money, and not just for tools, materials and workspace – the fact was, I needed the money generally. I was twenty-three – I needed to live, didn’t I? And as I saw it, money was simply part of the deal with Pa: subsidies, allowances and disbursements came with the terrain of his acquaintance. Besides, in the final analysis I was doing him a favour by taking his money – what else was he going to spend it on? Why shouldn’t he buy a flat for his kids if that was what made him happy?

Maybe buy, with its connotation of outright purchase, is not quite the right word, because that makes it sound as though Pa just reached into his pocket and handed over the cash. It did not happen that way. To finance the transaction, Pa had to remortgage his house, the family home at 75 Turtledove Lane. The agreement was that Rosie and I would pay what rent we could afford. Property was buoyant, Pa said. You’ll see, he told us happily as he showed us his name on the deeds, we’re going to come out of this smelling of roses.

Soon after Pa bought the flat the property market plunged. For two years now we have kept watch on the house prices, waiting for an end to their descent like spectators waiting for the jerking bloom of a skydiver’s parachute as he plummets towards the earth. But two years on, the prices are still falling and interest rates are still rising and Pa has to make whacking monthly payments which he cannot afford to make. Even so, he has never asked Rosie or me for a cent, with the result that no real rent has ever been paid. Now, there are reasons for this inexcusable situation. In my case, the answer is poverty: I’m broke. Unlike two years ago, though, at least now I experience genuine guilt about it. But by the operation of a circuitous, morally paralysing causality, somehow this guilt expiates its cause: the worse I feel about not paying Pa, the more penalized and thus virtuous and thus better I feel. As for Rosie – well, Rosie has other things to do with her money and no one, least of all Pa, is going to give her a hard time about that. Allowances have to be made as far as Rosie is concerned because allowances have always been made as far as Rosie is concerned. Besides, there is Steve. There is no point in being unrealistic about it – Steve is not the type to pay for anything. Steve lives for free.

And yet, despite all of this, Rosie sticks with him. It is hard to understand, to identify the perverse adherent at work between them. Rosie has wit, intelligence and beauty, and all of the Breezes have had a special soft spot for her for as long as anybody can remember. She has dark eyes set widely apart and a mane of auburn hair which ran until recently down her back like a fire. She is twenty-eight, two years older than me, and by any reasonable standard Steve Manus, agreeable though he is in his own way, is not fit to lick her boots. Rosie herself recognizes this, and although Steve shares her bed and her earnings, for some months now she has denied that he is her boyfriend.

‘It’s finished,’ she says. ‘You don’t think I’d stay with a creep like that, do you?’

But – but what about their cohabitation?

Rosie reads the question on my face. ‘He’s out of here,’ she says, ‘as soon as he finds somewhere to live. I’m not having that parasite in this house for one minute longer than I have to.’ We are in the kitchen. She raises her voice so that Steve, who is in the sitting-room, can hear her. ‘If the Slug doesn’t find a place by this time next month, that’s it, I’m kicking it out,’ she shouts. ‘Let it slime around on someone else’s floor for a change!’

Then the same thing always happens. Rosie goes away for two or three weeks to the other side of the world – Kuala Lumpur, Tokyo, Chicago – and by the time she descends from the skies we are back to square one. Square one is not a pleasant place to be. It is bad enough having Steve in the house, but when both he and my sister are here together for any length of time – usually when she has a spell of short-haul work – things become sticky.

It starts when Rosie comes home exhausted in the evening, still wearing her green and blue stewardess’s uniform. Instead of putting her feet up, she immediately spends an hour cleaning. ‘Look at this mess, just look at this pigsty,’ she says, furiously gathering things up – Steve’s things, invariably, because although fastidious about his personal appearance, he is just about the messiest and most disorderly person I know. On Rosie goes, rearranging cushions and snatching at newspapers. ‘Whose shoes are these? What about this plate – whose is that?’ Steve and I keep quiet, even if she is binning perfectly usable objects, because the big danger when Rosie comes home and starts picking things up is that she will hurl something at you. (Oh, yes, make no mistake, Rosie can be violent. In those split seconds of temper she will pick up the nearest object to hand and aim that missile between your eyes with a deadly seriousness. If she’s not careful, some day she will do somebody a real injury.) Rosie does not rest until she has filled and knotted a bin-liner and until she has hoovered the floors and scrubbed the sinks. She sticks to this routine even if the flat is already clean on her return. She puffs up the sofa, complains bitterly that the sink is filthy and redoes the washing up, which she claims has been badly done. (‘The glasses!’ she cries, holding aloft an example. ‘How many times do I have to tell you to dry the glasses by hand!’) Only once all of the objects in the sitting-room – many of which have remained untouched since they were moved by her the day before – have been fractionally repositioned does she finally relent. But what then? This is what concerns me, the horrified question I see expressed on my sister’s face once she has finished. What happens once everything is in its place?

Usually what happens next is that Steve gets it in the neck.

‘What have you done today?’ she demands.

‘Well,’ Steve says, ‘I’ve …’

‘You haven’t done anything, have you?’

The poor fellow opens his mouth to speak, then closes it again.

‘You’re pathetic,’ Rosie says quietly. ‘Don’t talk to me. Your voice revolts me.’ Then she lights a cigarette and momentarily faces the television, her legs crossed. She is still wearing her uniform. She inhales; the tip of her cigarette glitters. She turns around and looks Steve in the eye. ‘Well?’ Steve does not know what to say. Rosie turns away in disgust. ‘As I thought. Slug is too spineless to speak. Pathetic.’

‘I … No,’ Steve says bravely, ‘I’m not.’

Suddenly Rosie bursts into laughter. ‘No?’ She looks at him with amusement. ‘You’re not pathetic?’

‘No,’ Steve says with a small, uncertain smile.

‘Oh, you sweetie,’ Rosie says, sliding along the sofa towards him. Holding him and speaking in a baby voice, she says, ‘You don’t do anything, do you, honey bear? You just sit around all day and make a mess like a baby animal, don’t you, my sweet?’

Steve nods, happy with the swing of her mood, and nestles like a child in her arms. With luck, Rosie, who can be such good value when she is happy, has found respite from the awful, intransigent spooks that have somehow fastened on her, and we can all relax and get on with our evening.

How, then, do I put up with such horrible scenes? The answer is, by treating them as such: as scenes. It’s the only way. If I took their dramas to heart – if I let them come anywhere near my heart – I’d finish up like my father.

3

I have poured myself a glass of water. This waiting around is thirsty work, especially if, like me, you’re already dehydrated by a couple of lunchtime drinks. These came immediately after the refereeing débâcle, when Pa and I walked over to the nearest bar for a beer. Afterwards, the plan was, we were off back to Pa’s place to watch a proper game of football on the television: the relegation decider between Rockport United and Ballybrew. We Breezes, of course, follow United.

It was only when Pa returned with the drinks and took off his glasses to wipe the mud from them that I was able to observe his face closely. I thought, Jesus Christ.

It was his eyes. Looked at closely in the midday light, they were appalling. The eyeballs – I gasped when I saw the eyeballs: tiny red beads buried deep in violet pouches that sagged like emptied, distended old purses. Pa had always had troublesome old eyes, but now, I suddenly saw, things had gone a stage further. These were black eyes, the kind you got from punches; these were bona fide shiners.

How was this possible? How could this assault have happened?

I am afraid that the answer was painfully obvious. It was plain as pie that Pa has walked into every punch that life had swung in his direction. With his whole, undefensive heart, Pa has no guard. Every time a calamity has rolled along, there he has been to collect it right between his poor, crooked peepers. And in the last three days, of course, two real haymakers had made contact: first, the news that his job was in jeopardy; and second, Merv. It was doubtful that Pa had slept at all since Thursday night, the night of the crash.

I remembered the time I became acquainted with Merv: about four years ago, when I was looking for my first job and needed a suit for interviews. Pa said he had the answer to my problem. 'There’s this fellow in my office with a terrible curvature of the spine,’ he said, ‘but you’d hardly know it to look at him. He strolls around like a guardsman. It’s his suits that make all the difference,’ Pa said. 'The jackets fit him like gloves. There’s the man you want – the man who makes his suits.’

That was Merv – not the tailor, but the dapper hunchback. Every time I’ve met him I have been unable, hard as I might try, to keep my eyes off his back, off the hump, under his shirt.

Pa took a slug of his beer and threw me a packet of salt and vinegar crisps. Then he opened a packet of his own.

We sat there in silence for a few moments, crunching the potatoes. I said, ‘Are you sure you’re OK? You’re not looking well.’ He did not reply. I drank some beer and regarded him again. Then I said, ‘Listen, Pa. I know you don’t agree with me on this, but I really think you ought to consider packing in the reffing.’ Pa tilted his face towards the ceiling and tipped the last crumbs from the crisp packet into his mouth. ‘I’m not saying you should just sit at home doing nothing,’ I said. ‘Do something else. I don’t know, take up squash or something.’ No, that was too dangerous: I could just see him stretched out on the floor of the court, soaked in sweat and clutching his heart. ‘Or golf,’ I said. ‘Golf is a great game. Just give up the reffing. It isn’t worth it, Pa. You don’t get any thanks for what you do.’

Pa took a mouthful of beer and shook his head. ‘Johnny, I can’t. If I wasn’t there, who else would do it? Those kids rely on me. They’re counting on me to be there. Besides,’ he said, ‘I want to put something back into the game. Pay my dues.’

This last reason, especially, I did not and do not understand. The fact of the matter is that Pa, never having played the game, has not received anything from it which he could possibly pay back. Pa owes soccer nothing.

It was only thanks to me that he came into contact with football in the first place. I was eight years old and had begun to take part in Saturday morning friendlies in the park, and, along with the other parents, Pa took to patrolling the touch-line in his dark sheepskin coat. ‘Go on, Johnny!’ he used to shout as he ran up and down. ‘Go on, son!’ At first, my father was just like the other fathers, an ordinary spectator. But there came a day when he showed up in a track suit, the blue track suit he wears to this day with the old-fashioned stripes running down the legs. When, at half-time, he called the team together and the boys found themselves listening to his exhortations and advice, it dawned on them that Mr Breeze – a man who had never scored a goal in his life – had appointed himself coach. While Pa’s pep talks lacked tactical shrewdness, they were full of encouragement. ‘Never say die, men,’ he urged as we chewed the bitter chunks of lemon he handed out. ‘We’re playing well. We can pull back the four goals we need. Billy,’ he said, taking aside our tiny, untalented goalkeeper, ‘you’re having a blinder. Don’t worry about those two mistakes. It happens to the best of us. Keep it up, Sean,’ Pa said to our least able outfield player. ‘Don’t forget, you’re our midfield general.’

Pa’s involvement did not end there. No, pretty soon he had come up with a car pool, a team strip (green and white) and, without originality, a name: the Rovers. He organized a mini-league, golden-boot competitions, man-of-the-match awards, knock-out tournaments and, finally, he began refereeing games. He was terrible at it right from the start. Never having been a player himself, he had no idea what was going on. Offside, obstruction, handball, foul throw – Pa knew the theory of these offences but had no ability to detect them in practice. This incompetence showed, and mattered, even at the junior level of the Rovers’ matches between nine- and ten-year-olds. Needless to say, it was not much fun being the ref’s son. It made me an outsider in my own side.

I looked at my father, Eugene Breeze, sitting in front of me with his pint, resting. The creased, criss-crossed face, the leaking blue venation under the skin, the thin white hair pasted by sweat against the forehead. The red eyes blinking like hazard lights.

‘Pa,’ I said as gently as I could. ‘Face it. It’s time to quit. It’s time to move on to something else.’

He shrugged obstinately. ‘I’m not a quitter,’ he said.

That was true – he’s not a man to throw in the towel. When I stopped playing for the team – I must have been about eleven years old – Pa kept going. He kept right on refereeing the Rovers, running around the park every Saturday morning waist-deep in a swarm of youngsters. Even when the Rovers eventually disbanded, he did not give up. On the contrary, he decided to enter the refereeing profession properly. He bought himself a black outfit, boots with a bolt of lightning flashing from the ankle to the toe, red and yellow cards, a waterproof notebook and the Association Football rule book. Then one day he came home with a flushed face and a paper furled up in a pink ribbon. Wordlessly he handed me the scroll. I opened it and there it was in bold, splendid ink, Eugene Breeze, spectacularly printed in a large Gothic script.

This is to certify that Eugene Breeze is a Class E referee, the document announced. It was signed by Matthew P. Brett, Secretary of the Football Association.

‘Congratulations,’ I said. I was sixteen and laconic.

‘I took the exams and passed them straight off,’ Pa said. He retrieved the certificate from me and slapped it against his palm. ‘Do you realize, Johnny,’ he said, ‘do you realize that now I’m qualified?’

‘Great,’ I said. ‘You’re in the way,’ I said, leaning sideways to see the television.

‘This could lead anywhere.’ He shook the certificate as though it were a magical document of discovery and empowerment, a passport, blank cheque and round-the-world ticket rolled into one. ‘Who knows, with a bit of luck I could be refereeing professionally in a couple of years’ time, couldn’t I, Johnny? I mean, I know it sounds crazy, but it’s possible, isn’t it?’

That’s right, I said. It’s possible.

Possibilities! Pa, the numbskull, is a great one for possibilities. Stars in his eyes, he signed up officially with the Football Association and put his name down on the match list. He developed a scrupulous pre-match routine, ticking off checklists, boning up on the laws of the game and the weather reports, checking his studs and, late on the night before, ironing his kit and laying it out on the floor like a flat black ghost. But his dream of ascending the refereeing ladder did not materialize. For a while he took charge of good fixtures, games between ambitious young teenagers playing for serious clubs. But then, after his lack of ability became known and complaints had been made, the invitations dried up. ‘Never mind,’ he said to me eventually. ‘I’ll find my own level.’ That was when he took to wandering around football fields in his kit, haunting the touchlines, his silver whistle suspended unquietly from his neck. He would approach teams that were warming up and say, ‘Need a ref? Look, I’m qualified …’ and he would unfurl his certificate. Usually that was enough to do the trick, and that is how Pa has ended up where he is, officiating bad-tempered confrontations between pub teams and office XIs, ridiculed and bad-mouthed by players and onlookers alike. Even when he does well the abuse keeps coming, because the referee – that instrument of injustice – is never right. And still he persists and still, rain or shine, every weekend finds him out on the heath, looking for a game.

This state of affairs is unlikely to last for long, because Pa has become truly notorious for his incapability, even amongst occasional teams. One time he so mishandled a game that the players, unanimous in their infuriation, ordered him to leave the field; and so Pa is famous, in the small world of Rockport amateur football, for being the only referee ever to have been sent off. As a result, he is finding it harder and harder to get a game. Increasingly his polite offers of his services draw a blank and he has to content himself with running the line, waving the offsides with his red handkerchief. The day cannot be far away when my father finds that, like it or not, his officiating days are behind him.