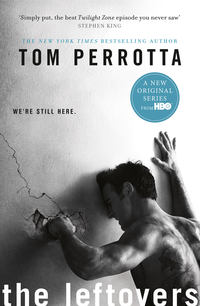

The Leftovers

Kevin attempted to make eye contact with Laurie throughout the sustained, somewhat defiant applause that followed, but she refused even to glance in his direction. He tried to convince himself that she was doing this against her will—she was, after all, flanked by two large bearded men, one of whom looked a little like Neil Felton, the guy who used to own the gourmet pizza place in the town center. It would have been comforting to think that she’d been instructed by her superiors not to fall into temptation by communicating, even silently, with her husband, but he knew in his heart that this wasn’t the case. She could’ve looked at him if she’d wanted to, could’ve at least acknowledged the existence of the man she’d promised to spend her life with. She just didn’t want to.

Thinking about it afterward, he wondered why he hadn’t climbed down from the stage, walked over there, and said, Hey, it’s been a while. You look good. I miss you. There was nothing stopping him. And yet he just sat there, doing absolutely nothing, until the people in white lowered their letters, turned around, and drifted back into the woods.

A WHOLE CLASS OF JILLS

JILL GARVEY KNEW HOW EASY it was to romanticize the missing, to pretend that they were better than they really were, somehow superior to the losers who’d been left behind. She’d seen this up close in the weeks after October 14th, when all sorts of people—adults, mostly, but some kids, too—said all kinds of crazy stuff to her about Jen Sussman, who was really nobody special, just a regular person, maybe a little prettier than most girls their age, but definitely not an angel who was too good for this world.

God wanted her company, they’d say. He missed her blue eyes and beautiful smile.

They meant well, Jill understood that. Because she was a so-called Eyewitness, the only other person in the room when Jen departed, people often treated her with creepy tenderness—it was as if she were a grieving relative, as if she and Jen had become sisters after the fact—and an odd sort of respect. No one listened when she tried to explain that she hadn’t actually witnessed anything and was really just as clueless as they were. She’d been watching YouTube at the crucial moment, this sad but hilarious video of a little kid punching himself in the head and pretending like it didn’t hurt. She must have watched it three or four times in a row, and when she finally looked up, Jen was gone. A long time passed before Jill realized she wasn’t in the bathroom.

You poor thing, they’d insist. This must be so hard on you, losing your best friend like that.

That was the other thing nobody wanted to hear, which was that she and Jen weren’t best friends anymore, if they ever had been, which she doubted, even though they’d used the phrase for years without giving it a second thought: my best friend, Jen; my best friend, Jill. It was their mothers who were best friends, not them. The girls just tagged along because they had no choice (in that sense they really were like sisters). They carpooled to school, slept at each other’s houses, went on combined family vacations, and spent countless hours in front of the TV and computer screens, killing time while their mothers drank tea or wine at the kitchen table.

Their makeshift alliance was surprisingly durable, lasting all the way from pre-K to the middle of the eighth grade, when Jen underwent a sudden and mysterious transfiguration. One day she had a new body—at least that’s the way it seemed to Jill—the next day new clothes, and the day after that new friends, a clique of pretty and popular girls led by Hillary Beardon, whom Jen had previously claimed to despise. When Jill asked her why she’d want to hang out with people she herself had accused of being shallow and obnoxious, Jen just smiled and said they were actually pretty nice when you got to know them.

She wasn’t mean about it. She never lied to Jill, never mocked her behind her back. It was like she just drifted slowly away, into a different, more exclusive orbit. She made a token effort to include Jill in her new life, inviting her (most likely on instructions from her mother) on a day trip to Julia Horowitz’s beach house, but all that really did was make the gulf between them more obvious than it had been before. Jill felt like a foreigner the whole afternoon, a pale and mousy interloper in her hopeless one-piece bathing suit, watching in silent bewilderment as the pretty girls admired one another’s bikinis, compared spray-on tans, and texted boys on candy-colored phones. The thing that amazed her most was how comfortable Jen looked in that strange context, how seamlessly she’d merged with the others.

“I know it’s hard,” her mother told her. “But she’s branching out and maybe you should, too.”

That summer—the last one before the disaster—felt like it would never end. Jill was too old for camp, too young to work, and too shy to pick up the phone and call anyone. She spent way too much time on Facebook, studying pictures of Jen and her new friends, wondering if they were all as happy as they looked. They’d taken to calling themselves the Classy Bitches, and almost every photo had that nickname in the heading: Classy Bitches Chillin’; Classy Bitches Slumber Party; Hey CB what ru drinking? She kept a close eye on Jen’s status, tracking the ups and downs of her budding romance with Sam Pardo, one of the cutest guys in their class.

Jen is holding hands with Sam and watching a movie.

Jen is THE BEST KISS EVER!!!

Jen is the longest two weeks of my life.

Jen is … WHATEVER.

Jen is Guys Suck!

Jen is All Is Forgiven (and then some).

Jill tried to hate her, but she couldn’t quite pull it off. What was the point? Jen was where she wanted to be, with people she liked, doing things that made her happy. How could you hate someone for that? You just had to figure out a way to get all that for yourself.

By the time September finally rolled around, she felt like the worst was over. High school was a clean slate, the past wiped away, the future yet to be written. Whenever she and Jen passed in the hall, they just said hi and left it at that. Every now and then, Jill would look at her and think, We’re different people now.

The fact that they were together on October 14th was pure coincidence. Jill’s mother had bought some yarn for Mrs. Sussman—the two moms were big on knitting that fall—and Jill happened to be in the car when she decided to drop it off. Out of old habit, Jill ended up in the basement with Jen, the two of them chatting awkwardly about their new teachers, then turning on the computer when they ran out of things to say. Jen had a phone number scribbled on the back of her hand—Jill noticed it when she pressed the power switch, and wondered whose it was—and chipped pink polish on her nails. The screen saver on her laptop was a picture of the two of them, Jill and Jen, taken a couple of years earlier during a snowstorm. They were all bundled up, red-cheeked and grinning, both of them with braces on their teeth, pointing proudly at a snowman, a lovingly constructed fellow with a carrot nose and borrowed scarf. Even then, with Jen sitting right beside her, not yet an angel, it felt like ancient history, a relic from a lost civilization.

IT WASN’T until her mother joined the G.R. that Jill began to understand for herself how absence could warp the mind, make you exaggerate the virtues and minimize the defects of the missing individual. It wasn’t the same, of course: Her mother wasn’t gone gone, not like Jen, but it didn’t seem to matter.

They’d had a complicated, slightly oppressive relationship—a little closer than was good for either of them—and Jill had often wished for a little distance between them, some room to maneuver on her own.

Wait’ll I get to college, she used to think. It’ll be such a relief not to have her breathing down my neck all the time.

But that was the natural order of things—you grew up, you moved out. What wasn’t natural was your mother walking out on you, moving across town to live in a group house with a bunch of religious nuts, cutting off all communication with her family.

For a long time after she left, Jill found herself overwhelmed by a childlike hunger for her mother’s presence. She missed everything about the woman, even the stuff that used to drive her crazy—her off-key singing, her insistence that whole-wheat pasta tasted just as good as the regular kind, her inability to follow the storyline of even the simplest TV show (Wait a second, is that the same guy as before, or someone else?). Spasms of wild longing would strike her out of nowhere, leaving her dazed and weepy, prone to sullen fits of anger that inevitably got turned against her father, which was totally unfair, since he wasn’t the one who’d abandoned her. In an effort to fend off these attacks, Jill made a list of her mother’s faults and pulled it out whenever she felt herself getting sentimental:

Weird, high-pitched totally fake laugh

Crappy taste in music

Judgmental

Wouldn’t say hi if she met me on the street

Ugly sunglasses

Obsessed with Jen

Uses words like hoopla and rigamarole in conversation

Nags Dad about cholesterol

Flabby arm Jello

Loves God more than her own family

It actually worked a little, or maybe she just got used to the situation. In any case, she eventually stopped crying herself to sleep, stopped writing long, desperate letters asking her mother to please come home, stopped blaming herself for things she couldn’t control.

It was her decision, she learned to remind herself. No one made her go.

THESE DAYS, the only time Jill consistently missed her mother was first thing in the morning, when she was still half-asleep, unreconciled to the new day. It just didn’t feel right, coming down for breakfast and not finding her at the table in her fuzzy gray robe, no one to hug her and whisper, Hey, sleepyhead, in a voice full of amusement and commiseration. Jill had a hard time waking up, and her mother had given her the space to make a slow and grumpy transition into consciousness, without a whole lot of chitchat or unnecessary drama. If she wanted to eat, that was fine; if not, that was no problem, either.

Her father tried to pick up the slack—she had to give him that—but they just weren’t on the same wavelength. He was more the up-and-at-’em type; no matter what time she got out of bed, he was always perky and freshly showered, looking up from the morning paper—amazingly, he still read the morning paper—with a slightly reproachful expression, as if she were late for an appointment.

“Well, well,” he said. “Look who’s here. I was wondering when you were gonna put in an appearance.”

“Hey,” she muttered, uncomfortably aware of herself as the object of parental scrutiny. He eyeballed her like this every morning, trying to figure out what she’d been up to the night before.

“Bit of a hangover?” he inquired, sounding more curious than disapproving.

“Not really.” She’d only had a couple of beers at Dmitri’s house, maybe a toke or two off a joint that made the rounds at the end of the night, but there was no point in going into detail. “Just didn’t get enough sleep.”

“Huh,” he grunted, not bothering to hide his skepticism. “Why don’t you stay home tonight? We can watch a movie or something.”

Pretending not to hear him, Jill shuffled over to the coffeemaker and poured herself a mug of the dark roast they’d recently started buying. It was a double-edged act of revenge against her mother, who hadn’t allowed Jill to drink coffee in the house, not even the lame breakfast blend she thought was so delicious.

“I can make you an omelette,” he offered. “Or you can just have some cereal.”

She sat down, shuddering at the thought of her father’s big sweaty omelettes, orange cheese oozing from the fold.

“Not hungry.”

“You have to eat something.”

She let that pass, taking a big gulp of black coffee. It was better that way, muddy and harsh, more of a shock to the system. Her father’s eyes strayed to the clock above the sink.

“Aimee up?”

“Not yet.”

“It’s seven-fifteen.”

“There’s no rush. We’re both free first period.”

He nodded and turned back to his paper, the way he did every morning after she told him the same lie. She was never quite sure if he believed her or just didn’t care. She got the same distracted vibe from a lot of the adults in her life—cops, teachers, her friends’ parents, Derek at the frozen yogurt store, even her driving instructor. It was frustrating, in a way, because you never really knew if you were being humored or actually getting away with something.

“Any news on Holy Wayne?” Jill had been following the story of the cult leader’s arrest with great interest, grimly amused by the sordid details included in the articles, but also embarrassed on behalf of her brother, who’d cast his lot with a man who turned out to be a charlatan and a pig.

“Not today,” he said. “I guess they used up all the good stuff.”

“I wonder what Tom will do.”

They’d been speculating about this for the past few days but hadn’t gotten too far. It was hard to imagine what Tom might be thinking when they didn’t know where he was, what he was doing, or even if he was still involved with the Healing Hug Movement.

“I don’t know. He’s probably pretty—”

They stopped talking when Aimee walked into the kitchen. Jill was relieved to see that her friend was wearing pajama bottoms—it wasn’t always the case—though the relative modesty of this morning’s outfit was undercut by a cleavage-baring camisole. Aimee opened the refrigerator and peered into it for a long time, tilting her head as if something fascinating was going on in there. Then she pulled out a carton of eggs and turned toward the table, her face soft and sleepy, her hair a glorious mess.

“Mr. Garvey,” she said, “any chance you could whip up one of those yummy omelettes?”

AS USUAL, they took the long way to school, ducking behind the Safeway to smoke a quick joint—Aimee did her best not to set foot inside Mapleton High without some sort of buzz going—then heading across Reservoir Road to see if anyone interesting happened to be hanging out at Dunkin’ Donuts. The answer, not surprisingly, turned out to be no—unless you thought old men gnawing on crullers qualified as interesting—but the moment they poked their heads in, Jill was overcome by a wicked sugar craving.

“You mind?” she asked, glancing sheepishly toward the counter. “I didn’t have any breakfast.”

“I don’t mind. It’s not my fat ass.”

“Hey.” Jill swatted her in the arm. “My ass isn’t fat.”

“Not yet,” Aimee told her. “Have a few more donuts.”

Unable to decide between the glazed and the jelly, Jill split the difference and ordered both. She would’ve been perfectly happy to eat on the run, but Aimee insisted on getting a table.

“What’s the hurry?” she asked.

Jill checked the time on her cell phone. “I don’t wanna be late for second period.”

“I have gym,” Aimee said. “I don’t care if I miss that.”

“I have a Chem test. Which I’m probably gonna fail.”

“You always say that, and you always get As.”

“Not this time,” Jill said. She’d skipped too many classes in the past few weeks, and had been stoned for too many of the ones she’d managed to attend. Some subjects mixed okay with weed, but Chemistry wasn’t one of them. You get high and start thinking about electrons, and you can end up a long way from where you’re supposed to be. “This time I’m screwed.”

“Who cares? It’s just a stupid test.”

I do, Jill wanted to say, but she wasn’t sure if she meant it. She used to care—used to care a lot—and hadn’t quite gotten used to the feeling of not caring, though she was doing her best.

“You know what my mom told me?” Aimee said. “She said that when she was in high school, girls could get out of gym just for having their period. She said there was this one teacher, this Neanderthal football coach, and she told him every class that she had cramps, and he always said, Okay, go sit in the bleachers. The guy never even noticed.”

Jill laughed, even though she’d heard the story before. It was one of the few things she knew about Aimee’s mother, besides the fact that she was an alcoholic who’d disappeared on October 14th, leaving her teenage daughter alone with a stepfather she didn’t like or trust.

“You want a bite?” Jill held out her jelly donut. “It’s really good.”

“That’s okay. I’m stuffed. I can’t believe I ate that whole omelette.”

“Don’t blame me.” Jill licked a tiny jewel of jelly off the tip of her thumb. “I tried to warn you.”

Aimee’s expression turned serious, even a bit stern.

“You shouldn’t make fun of your father. He’s a really nice guy.”

“I know.”

“And he’s not even a bad cook.”

Jill didn’t argue. Compared to her mother, her father was a terrible cook, but Aimee had no way of knowing that.

“He tries,” she said.

She scarfed down her glazed donut in three quick bites—it was so airy inside, almost like there was nothing beneath the sugary coating—then gathered up her trash.

“Ugh,” she said, dreading the prospect of the test she was about to take. “I guess we better go.”

Aimee studied her for a moment. She glanced at the display case behind the counter—tiers of donuts arrayed in their metal baskets, iced and sprinkled and powdered and plain and full of sweet surprises—and then back at Jill. A mischievous smile broke slowly across her face.

“You know what?” she said. “I think I will have something to eat. Maybe some coffee, too. You want coffee?”

“We don’t have time.”

“Sure we do.”

“What about my test?”

“What about it?”

Before Jill could reply, Aimee was out of her seat, moving toward the counter, her jeans so tight and her stride so liquid that everyone in the place turned to stare.

I have to go, Jill thought.

A feeling of unreality came over her just then, a sudden awareness of being trapped in a bad dream, that panicky sense of helplessness, as if she possessed no will of her own.

But this was no dream. All she had to do was stand up and start walking. And yet she remained frozen in her pink plastic seat, smiling foolishly as Aimee turned and mouthed the word Sorry, though it was clear from the look on her face that she wasn’t sorry at all.

Bitch, Jill thought. She wants me to fail.

AT MOMENTS like this—and there were more of them than she would have liked to admit—Jill wondered what she was doing, how she’d allowed herself to get so tangled up with someone as selfish and irresponsible as Aimee. It wasn’t healthy.

And it had happened so quickly. They’d only gotten to know each other a few months ago, at the beginning of summer, two girls working side by side in a failing frozen yogurt store, chatting during the slow times, some of which lasted for hours.

They were wary of each other at first, conscious of their membership in different tribes—Aimee sexy and reckless, her life a cluttered saga of bad decisions and emotional melodrama; Jill straitlaced and reliable, an A student and model teenage citizen. I wish I had a whole class of Jills, more than one teacher had written in the comments box on her report card. No one had ever written that about Aimee.

As the summer wore on, they began to relax into what felt like a genuine friendship, a connection that made their differences seem increasingly trivial. For all her social and sexual confidence, Aimee turned out to be surprisingly fragile, quick to tears and violent bouts of self-loathing; she required a lot of cheering up. Jill was better at hiding her sadness, but Aimee had a way of coaxing it out of her, getting her to open up about things she hadn’t discussed with anyone else—her bitterness toward her mother, her trouble communicating with her father, the feeling that she’d been cheated, that the world she’d been raised to live in no longer existed.

Aimee took Jill under her wing, bringing her to parties after work, introducing her to what she’d been missing. Jill was intimidated at first—everybody she met seemed a little older and a little cooler than she was, even though most of them were her own age—but she quickly overcame her shyness. She got drunk for the first time, smoked weed, stayed up till dawn talking to people she used to ignore in the hallway, people she’d written off as losers and burnouts. One night, on a dare, she took off her clothes and jumped into Mark Sollers’s pool. When she climbed out a few minutes later, naked and dripping in front of her new friends, she felt like a different person, like her former self had been washed away.

If her mother had been home, none of it would have happened, not because her mother would’ve stopped her, but because Jill would’ve stopped herself. Her father tried to intervene, but he seemed to have lost faith in his authority. He grounded her once in late July, after finding her passed out on the front lawn, but she ignored the punishment and he never mentioned it again.

Nor did he complain when Aimee started sleeping over, even though Jill hadn’t consulted him before inviting her. By the time he finally got around to asking what was up, Aimee was already a fixture in the house, sleeping in Tom’s old bedroom, adding her own peculiar requests to the family shopping lists, the kind of stuff that would have given her mother a heart attack—Pop-Tarts, Hot Pockets, ramen noodles. Jill told the truth, which was that Aimee needed a break from her stepfather, who sometimes “bothered” her when he came home drunk. He hadn’t touched her yet, but he watched her all the time and said creepy things that made it hard for her to fall asleep.

“She shouldn’t live there,” Jill told him. “It’s not a good situation.”

“Okay,” her father said. “Fair enough.”

The last two weeks of August were especially giddy, as if both girls sensed an expiration date on the fun and wanted to drink every drop while they still could. One morning, Jill came down from the shower, complaining about how much she hated her hair. It was always so dry and lifeless, nothing like Aimee’s, which was soft and radiant and never looked bad, not even when she’d just rolled out of bed in the morning.

“Cut it off,” Aimee told her.

“What?”

Aimee nodded, her face full of certainty.

“Just get rid of it. You’ll look better without it.”

Jill didn’t hesitate. She went upstairs, hacked away at her dull tresses with a pair of sewing scissors, then finished the job with the electric clippers her father kept under the bathroom sink. It was exhilarating to feel the past falling away in clumps, to watch a new face emerge, her eyes big and fierce, her mouth softer and prettier than it used to be.

“Holy shit,” Aimee said. “That is fucking awesome.”

Three days later Jill had sex for the first time, with a college guy she barely knew, after a drunken spin-the-bottle marathon at Jessica Marinetti’s house.

“I never did it with a bald girl,” he confided while they were still in the middle of the act.

“Really?” she said, not bothering to inform him that she’d never done it at all. “Is it okay?”

“It’s nice,” he told her, nuzzling her scalp with the tip of his nose. “Feels like sandpaper.”

She didn’t start to feel self-conscious until school started and she saw the way her old friends and teachers looked at her when she walked down the hall with Aimee, the mix of pity and loathing in their eyes. She knew what they were thinking—that she’d been led astray, that the bad girl had corrupted the good one—and wanted to tell them that they were wrong. She was no victim. All Aimee had done was show her a new way of being herself, a way that made as much sense right now as the old way had before.

Don’t blame her, Jill thought. I made the choice.

She was grateful to Aimee, she really was, and glad she’d been able to help her out with a place to stay when she needed it. Even so, all this togetherness was starting to get to her, the two of them living like sisters, sharing clothes and meals and secrets, partying together every night and then starting up again in the morning. This month they even got their periods at the same time, which was kind of freaky. What she needed was a breather, a little time to catch up on schoolwork, hang out with her dad, maybe go through some of the college material that kept arriving in the mail every day. Just a day or two to get her bearings, because sometimes she had a little trouble locating the boundary between the two of them, the place where Aimee left off and Jill began.