Postcards

In the diner hunched over the cup of coffee he wonders how far he is going.

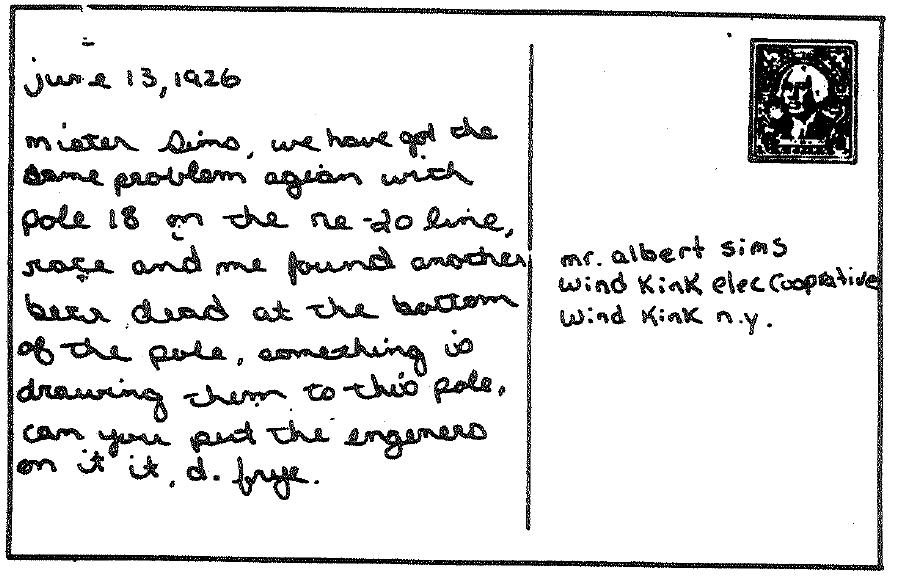

5 A Short, Sharp Shock

THE BEAR, LIKE MANY BEARS, had led a brief and vivid life. Born in the late winter of 1918 in a stump den, he was the oldest of two cubs. In personality he was quarrelsome and insensitive to the subtle implications of new things. He ate the remains of a poisoned eagle and nearly died. In his second autumn, from the height of a cliff, he saw his mother and sister backed against an angle in the rock by lean bear hounds. They went down in squalling that drew nothing but dry rifle fire. He was hunted himself the same year but escaped death and injury until 1922 when a coffin maker’s charge of broken screws swept up from the shop floor smashed his upper left canine teeth, leaving him unbalanced in mind and with chronic abscesses.

The next summer McCurdy’s Lodge, a massive structure of dovetailed spruce logs and carved cedar posts, opened on the eastern side of his range. The bear’s sense of smell was sharpened by hunger. He came to the Lodge’s garbage dump and its exotic peach peelings, buttered crusts and beef fat that melted in his hot throat. He began to lurk impatiently in the late afternoon trees for the cook’s helper with his wheelbarrow of orange peel and moldy potatoes, celery stumps and chicken bones, trickles of sardine oil.

The helper was a lumber-camp cook learning the refinements of carriage trade cuisine. He saw the bear in the dusk and ran shouting up to the Lodge for a ride. Hotelier McCurdy was in the kitchen talking Toumedos forestier with the cook and went to look at the bear for himself. He saw something in the hulking shoulders, the doggy snout, and told the Lodge carpenters to build benches on the slope above the dump. They set the area off with a peeled sapling railing to mark the limits of approach. The bolder guests walked twittering through the birches to see the bear. They touched each other’s shoulders and arms, their hands sprang protectively to their throats. The laughter was choked. The bear never looked up.

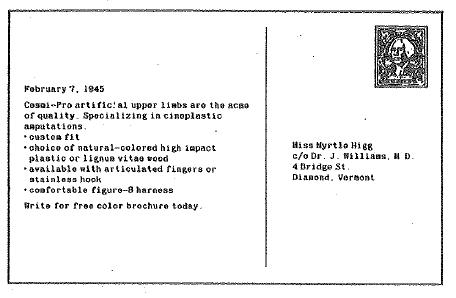

Through the summer the guests watched the bear flay the soft, fly-spangled garbage with his claws. The men wore walking suits or flannel bags and argyle pullovers, the women came in wrinkled linen tubes with sailor collars. They lifted their Kodaks, freezing the sheen of his fur, his polished claws. Oscar Untergans, a timber-lot surveyor who sold hundreds of nature shots to postcard printers photographed the bear at the summer dump. Untergans came again and again, walking along the path behind the cook, picking up any fetid rinds or dull eggshells thrown from the jouncing wheelbarrow. Sometimes the bear was waiting. The cook pitched the garbage with a pointed spade. He hit the bear with rotted tomatoes, grapefruit halves like yellow skullcaps.

Two or three summers after Untergans snapped the bear’s image they ran electric line to the Lodge. One evening the bear did not appear at the dump, nor was he seen in the following weeks and years. The Lodge burned on New Year’s Eve of 1934. On a rainy May night in 1938 Oscar Untergans fell in his estranged wife’s bathroom and died from a subdural haematoma. The postcard endured.

6 The Violet Shoe in the Ditch

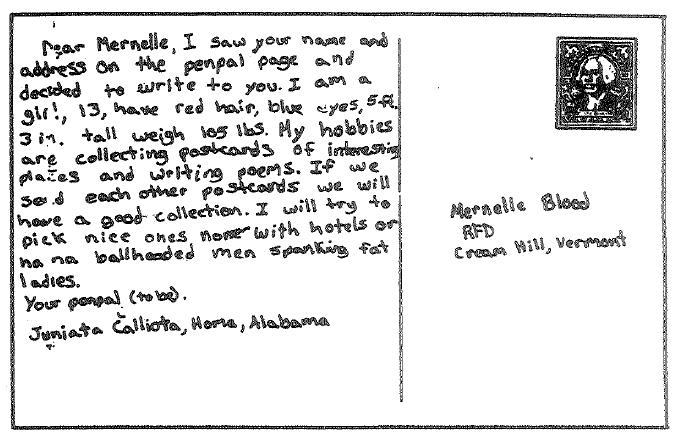

MERNELLE SLOGGED DOWN the steep road, the snow packing into her boots. The dog plunged into her tracks, up and out, like a roller coaster. ‘You’re knockin’ yourself out for nothin’,’ she said. ‘Nobody’s sendin’ you no letters or postcards. No penpals for dumb dogs. I can guess what you’d write. Stuff like “Dear Fido, Send me a cat. Wufwuf, Dog.”’

Later Mink would get out the snow roller that the town had sold him cheap when they went over to the snowplow and hitch it to the tractor. The roller was a slatted rolling pin of a thing that crushed the snow down into a smooth pack. After the roller went up and down the truck still couldn’t make it, even with chains. In November, before the big snows came, Mink parked the truck at the bottom of the road. He hauled the forty-quart cream cans down every morning with the tractor.

‘Leave the truck up here, we run the risk of bein’ trapped for the winter. This way we got at least a chance if the place catches on fire or somebody gets hurt bad. Get down to the road, we got a ride.’ That was Jewell talking through Mink’s mouth. Jewell was the one afraid of accidents and fire, had seen her father’s barns burn down with the horses and cows inside. Had seen her oldest brother die after they pulled him out of the well, the rotten cover hidden by years of overgrown grass. She told the story in a certain way. Cleared her throat. Began with a silence. Her fingers interlaced, wrists balanced on her breasts and as she told her hands rocked a little.

‘He was smashed up terrible. Every bone in him was broken. That well was forty foot down, and he pulled stone on top of hisself as he was falling, just hit a stone and it’d come right out. They had to move eighteen rocks off him, some of them weighed more than fifty pound, before they could get him out. Those stones come up one by one, real careful so they wouldn’t jar no more loose. You could hear Marvin down there, “unnnh, unnnh,” just didn’t stop. Steever Batwine was the one went down in there to get him out. It was awful dangerous. The rest of the well could of caved in any minute. Steever liked Marvin. Marvin had did some work for him that summer, helped with the hayin’, and Steever said he was a good hand. Well, he was a good hand, only twelve but already real strong. The rocks they were pulling up could of come loose from the sling and beaned Steever.’ Dub always laughed when she said ‘beaned.’

‘Marvin’s the one you’re named after,’ she said to Dub, ’Marvin Sevins, so don’t laugh.

‘Then they put down a like little table with the legs pulled off it, put the table in the sling and lowered it down. The table only got halfway down when it stuck and they had to bring it back up and saw the end off before it could fit. Steever was down there expecting more rocks to come any minute. He picked up Marvin and laid him on the table. He screamed terrible when Steever gathered him up to put him on the table, then went back to moaning. Steever said the only thing holding him together was his skin, he was like a armful of kindling inside. When Marvin come out of the well on the little table all black and blue and covered with blood and dirt and his legs twisted like cornstalks my mother fainted. Just swooned right down and laid there in the dirt. The hens come pecking over by her and this one hen I always hated afterwards, just stepped in her hair and looked in her face like it was thinking about pecking her eye. I was only five or so, but I knew that hen was a bad one and I got a little stick and took after it. So they brought Marvin into my mother and father’s room and the hired man, he was just a young fellow from the Mason’s place was the one that started to wash off the blood. He was real gentle about it, but he could hear this crackling like paper when he wiped off Marvin’s forehead, and he seen it wasn’t no use, so he put down the bloody washrag in the basin very soft and he went out. Took Marvin all night to die, but he never opened his eyes. He was unconscious. My mother never went into that room once. Just stayed out in the parlor fainting and crying by turns. I held that against her for years.’ And the mother’s brutal selfishness of grief again thrown up like a billboard for everyone to see and shudder. Grandma Sevins.

Mernelle was sweating inside her woolen snowsuit when she reached the bottom of the hill. The town road was plowed and empty, the snow corrugated with patterns of tire treads and chains. The mailman’s track, an old Ford sedan with the back end sawed off and a plank bed and slatted tides added on, left a distinctive pattern. You could hear it coming a long way off, the loose links clacking and rattling. Mernelle could tell if the mailbox was empty, just the disappointing gnaw of hinges, when the tire tracks ran down the middle of the road without slewing in.

Usually she walked all the way down, anticipating something, maybe a mysterious buff envelope addressed to her father, and when he slit it open with his old caked penknife a green check for a million dollars would slide out onto the table.

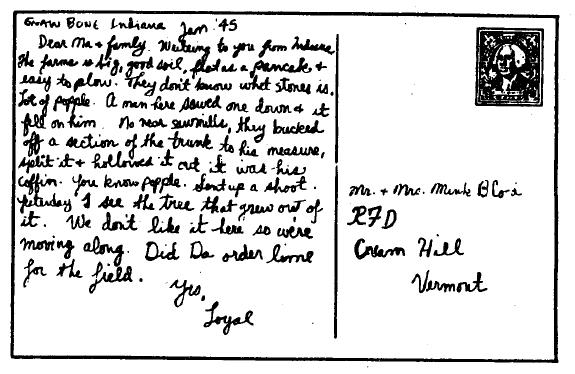

There was mail. Loyal’s Farm Journal that kept coming even though he was gone, a cattle auction flyer, a postcard for her mother that the Watkins man was coming the first week in February. At the bottom he’d scrawled ‘whether permiting.’ Another bear postcard for Jewell, written in Loyal’s handwriting, so small it was a nuisance to read it. There was a postcard for her, the third piece of mail of her life. She counted them. The birthday card from Miss Sparks when Loyal was going out with her. The letter from Sergeant Frederick Hale Bottum. And this.

She hadn’t told her mother that Sergeant Frederick Hale Bottum wrote that she should send him a picture, a snapshot, he wrote, ‘in a cute two piece bathing suit if you got one but one piece is ok. I know your cute by your cute name. Write to me.’ She sent a bathing suit picture of her cousin Thelma rummaged from the tin box in the pantry where letters and photographs curled. Thelma was fourteen in the snapshot, her arms and legs like rakes. She squinted, looked Mongolian. The Atlantic Ocean was flat. It was a tan bathing suit, sewed at home by Aunt Rose. When it was wet it sagged like old skin. In the photograph it was wet and sandy.

This postcard showed a white-columned building behind trees swathed in angry green moss. ‘An Old Southern Mansion.’

Dog was running up and down the plowed road, digging his toenails in and racing for the bend, then turning on a dime, kicking up a spurt of snow in the tight circle and racing back to Mernelle again. His happiness matched up with her getting a postcard. His fur was yellow against the snow. The snowplow had cut the banks far back and leveled them off in two tiers, ready for February and March storms. The blade had pulled up thousands of sticks and leaves like pieces of bat wings. Dog raced off again, around the bend this time.

‘You get back here. I’m goin’ home. Milk truck’ll run over you.’

But she walked toward the bend herself for the pleasure of feeling the firm road underfoot after a mile and a half of wallowing. ‘Juniata Calliota Homa Alabarna’ she sang. Dog was rolling in the novelty of leaves, sweeping them with his gyrating tail. He looked at her.

‘Come on,’ she said, slapping her thigh. ‘Let’s go.’ When he ran willfully away from her in the direction of the village, she turned back without him, the mail in her coat pocket. She was almost to the culvert, the brook frozen inside, when he caught up with her. He had brought her something, but didn’t want to give it up, like a child bringing a birthday present to a party. She wrestled it out of his wet jaws. It was a woman’s shoe with a strap, a pale lilac color, stained and half full of leaves, the silk wet where Dog had mouthed it.

‘Dog. Dog, look!’ Mernelle made to throw the slipper, feinted. Dog’s eyes got the deep hunting gleam. He stiffened, watched her hand with everything he had. She threw the slipper and he marked where it fell, then plunged into the snow for the prize. It took them all the way home and she threw it for the last time, up onto the milk house roof. And went in singing.

‘How come he don’t put no return address on these things,’ asked Jewell, turning the postcard over and frowning at the bear. ‘How does he expect us to answer him? How are we supposed to tell him anything that’s went on?’ Jewell asked Mink. This question could not be asked.

‘Don’t mention the son of a bitch’s name to me. I don’t want to hear from him.’ Mink jerked on his extra socks. His shoulders sloped in the stiff work shirt, the mark of the iron on the smooth sleeves. His hairy hands came out of the cuffs and grasped.

‘You can send it to General Delivery of the place that’s postmarked,’ said Dub.

‘Chicago? Even I know that’s too big a place to send General Delivery.’

‘You gonna gas all day or can we get on with the milkin’?’ said Mink. His arms were in the barn coat, he slotted the buttons through the stretched holes. ‘I want to look over these cows, decide which ones we’re goin’ to sell to get down to where we can manage. If we can manage. Right now there’s not enough money in the damn milk checks to do more than buy shoes and tractor gas.’ The feed cap, greasy bill tilted at the door.

Dub gave his foolish smile and thrust into barn boots. The laces trailed. He followed as close behind Mink as a dog.

In the barn sweet breath of cows, splattering shit, grass dust sifting down from the loft.

‘Them cows has got to pay the taxes and the fire insurance. And your mother don’t know it, but we are a long way behind in the mortgage department.’

‘What’s new,’ said Dub, burying himself in the dark corner, wrenching the pump handle until the water shot out. Began to fill buckets. ‘ “Oh the farmer’s life is a happy life.” ’ He sang the old Grange song with the usual cracked irony. Had anybody ever sung it another way?

7 When Your Hand Is Cut Off

DUB HAD HIS NEWSPAPER CLIPPING, and for three years he’d kept it in a bureau drawer that would hardly open.

Marvin E. Blood of Vermont was injured after he jumped from a moving freight train entering Oakville, Ct. and slipped under a boxcar. He was taken to St. Mary’s Hospital where his left arm was amputated above the elbow. Oakville Police Chief Percy Sledge said, ‘Men are bound to be injured if they ride the rods. This young man’s strength should have gone to the War effort, but he has become a burden to his family and the community.’

Mink and Jewell had to drive down to the hospital in Connecticut to get him. Mink stared at the empty sleeve of the donated corduroy jacket and said, ‘Twenty-four years old and look at you. Jesus Christ, you look like a hundred miles of bad road. If you’d did your hellin’ around up at home you wouldn’t be in this mess.’

Dub grinned. He’d grin at a funeral, Mink thought. ‘Gonna have somebody sew that onto my pajamas,’ Dub said. But it was no joke. And when Dub saw the package store on the street in Hartford he told Mink to pull over.

It was hard, opening the pint with just one hand. The cap seemed sweated on. He clenched the bottle between his knees, spit on his fingers and twisted until his fingers cramped. ‘Ma?’ he said.

‘I never opened a bottle of that poison for anybody in my life and I won’t start now.’

‘Ma, I need you to do it. If you don’t I’ll probably bite the top of the goddamn bottle off.’

Jewell stared fixedly at the horizon, her hands folded hard into each other. They traveled another mile. Dub’s breathing filled the car.

‘God’s sake!’ shouted Mink, swerving over to the grassy verge. ‘God’s sake, give me the damn thing.’ He bore down on the cap until it gave a crack and spun free. He passed it back to Dub. The smell of the whiskey flowed out, a heavy smell like roasted sod after a brush fire. Jewell cranked her window partway open and for the two hundred miles north Dub said nothing about the air that chilled him until he shook and had to drink more whiskey to see straight.

They’d known he was a fool since he was a baby, but now they had the firsthand proof he was a cripple and a drunk, too.

It was a little easier, Dub thought, since they’d culled four of the cows, but they still didn’t get done with the evening milking until six-thirty or later. Even if he skipped supper he still had to clean up and get the stink of the barn off him. No matter what he did, whether he took a bath, sliding under the grey water, or scrubbed his arms and neck with Fels Naptha until his skin burned, the rich mingle of manure, milk and animal came off him like heat when he danced with Myrt. But on Saturday night after the milking he cleaned up and took off for the Comet Roadhouse. Try and stop him.

It was cold. The truck wouldn’t turn over until he set the hot teakettle on the battery for half an hour. He probably wouldn’t be able to start it again at midnight when the Comet dosed, but he didn’t care now and a kind of impatient joy sent him skidding around the gravelly curves, running the intersection stop sign. He didn’t see any lights coming. He rushed toward the Comet’s warmth.

The parking strip was full by the time he got there. Over the roadhouse’s roof the red neon comet and its hot letters glowed in the icy night. Ronnie Nipple’s truck, with a load of wood in the back to give some traction on the lull, was parked at the far end of the row of cars and trucks. The snow squeaked as Dub cramped the tires and pulled up beside it. He could probably get a jump from Ronnie if he had to. Or Trimmer, if he was here. He looked down the row for Trimmer’s woods truck but didn’t see it. His breath gushed out, building up an edge of time on the windshield where the heater air hadn’t warmed it. He dammed the truck door, but the worn catch didn’t hold and it bounced open again. ‘Fuck it, no time to fool around with that.’ He ran toward the door with its frosted glass and jingling bell, anxious to dive into the roar of sound he heard coming from inside.

The steamy, smoke-hot room sucked him in. The tables were jammed, the bar was a row of bent backs and shoulders. The jukebox glowed with colored bubbles, saxophones flaring, gurgling out of the bubbles. He threw himself toward the fire of wooden matches, the glint of beer bottles, the mean little half-moon smiles of emptying shot glasses. He stood on the bar rail and looked for Myrtle, looked for Trimmer.

‘How the hell do you get it so hot in here,’ he shouted at Howard who was rushing back and forth behind. The bartender turned his long yellow face toward Dub. The sagging smoke-discolored skin seemed fastened in place by a pair of black metallic eyebrows. The mouth opened in a grimace of recognition. A wet tooth winked.

‘Body heat!’

A man at the bar laughed. It was Jack Didion. His arm hugged the older woman next to him, wearing a long baggy dress printed with navy blue chevrons. She worked at Didion’s, milked cows, wore men’s overalls all week. Didion whispered something in the woman’s ear and she threw back her head and roared. ‘Body heat! You said it!’ Her broken fingernails were rimmed with black.

The colored bottles stood in a pyramid. After Howard’s wife died he had taken the round mirror etched with bluebirds and apple blossoms from her dressing table and hung it on the wall behind the bottles so their number was doubled in richness and promise. Howard, too, was doubled as he passed back and forth, the back of his head reflected among the bottles.

The little stage at the end of the bar was dark, but the microphones were set up, there was the drum set. A cardboard sign on the easel – THE SUGAR TAPPERS in glitter-dust letters. Dub, gyring through the dancers, saw Myrtle at a table against the wall, leaning out into the throbbing light so she could watch the door. He came up behind her and put his cold hand on the back of her neck.

‘My god! You could kill a person that way! What took you so long, as if I didn’t know.’ Her brown hair was screwed into a chignon that had slipped its moorings and rode low on her neck. Her mouth was drawn with lipstick into a hard little crimson kiss. She wore her secretary suit with its ruffled blouse. Her small eyes were a clear teal blue fringed with sandy lashes. Her shallow face and flat chest made her look weak and vulnerable, and Dub enjoyed that illusion. He knew she was as tough as oak, a trim, tough little oak.

‘What always takes me so long; milking, washing up, get the truck going, drive down here. We didn’t get through the milking until late. Usually I don’t care, but tonight I was goin’ crazy tryin’ to get out. He was just squeezin’ slow, I guess. What a fuckin’ hopeless mess.’

‘Did you tell him?’

‘No, I didn’t tell him. He’ll go through the wall. Want to make sure the rifles are all locked up before I tell him. I thought he got a little mad when Loyal took off, but it’ll really rattle his marbles when I drop the word we’re getting hitched and moving out.’

‘It isn’t going to get any easier the longer you put it off.’

‘There’s a lot more to it than just telling him. I can’t clear out until I know he’s got a way to get out from under that farm. Sell it, is what I think he ought to do. Then I got to come up with some money. Some real money. It’s o.k. for us to talk about moving off, about me taking the piano tuning course and all, but money is what makes it happen and I don’t got any.’

‘It always comes down to money. That’s what we always end up talking about. It never fails.’

‘It’s the big problem. He don’t say much, but I know damn well the mortgage and the taxes is way behind. He ought to sell but he’s so damn stubborn he won’t. I try to mention it he says “I-was-born-on-this-farm,-I’ll-die-on-this-farm,-farmin’s-the-only-thing-I-know.” Hell, if I can learn piano tuning he could learn something different. Run a drill press or something. Want a beer? Fizzy drink? A martini?’ His voice puffed, rich, comic.

‘Oh, I might as well have have a gin and ginger ale.’ She pushed the chignon up and drove another hairpin into the slippery mass.

‘The one I feel sorry for is Mernelle. She runs up there to her room cryin’ because she don’t have any decent clothes. She’s grown out of everything. She had to wear one of Ma’s dresses to school the other day. Come home bawlin’. I feel bad, but there’s not a damn thing I can do about it. I know how she feels when the kids pick on you. Rotten little bastards.’

‘Poor kid. Listen, I got some dresses and a skirt and sweater she can have. A nice green cashmere sweater and a brown corduroy skirt.’

‘Honey, she’s six inches taller than you and about twenty pounds skinnier. That’s the problem. She’s shot up wicked the last few months. Bean pole. Wish she could put the brakes on.’

‘We’ll think of something. She can’t wear Jewell’s dresses to school, poor kid. By the way, I’ve got a surprise for you.’

‘Better be good.’

‘I think so.’ The inverted red prints of her lips mapped the rim of the glass. ‘Doctor Willy got a postcard from the Railway Express today. It’s in.’

‘What’s in?’

‘You know. You know what I mean. What you were measured for.’ Her face washed red. She could not say it, not after two years as the doctor’s secretary and appointment manager. Not after seven months of sitting with Dub in the farm truck that leaked mosquitoes, engine fumes, road water, and leg-paralyzing cold, kissing and planning a hundred escapes and futures and every one without a farm in it.

‘Oh yeah, you must mean the fancy arm. The prosthesis. That what you mean?’

‘Yes.’ She pushed the stained glass away from her. She could not stand to hear him breathe that way.

‘Or is it a hook, big shiny, stainless steel hook? I forget. I only know my girlfriend Myrt says I gotta get one, but she can’t say what it is I gotta get.’

‘Marvin. Don’t do this to me,’ she said in a low voice.

‘Don’t do what? Say “hook”? Say “prosthesis”?’ His voice rolled out across the dance door. He saw Trimmer at the bar, saw Trimmer cross his eyes and draw his hand across his throat. All at once he felt better and began to laugh. He pulled the cigarette pack from his shirt pocket and shook out a cigarette. ‘Don’t be embarrassed, honey. I hate to say it, too. “Prosthesis.” Sounds like a nasty poison snake. “He was bit by a prosthesis.” That’s how come I been so long without doing anything about it. Couldn’t say it. Atta girl, big sweet smile for the mutt. I’ll tell you, little girl, a couple months after it happened I hitched down to this place in Rhode Island where you can get fitted for something, the hook, I think, but I couldn’t go in. I was too embarrassed to go in. I could see the girl sitting there at the desk, and I just couldn’t go up to her and say—’