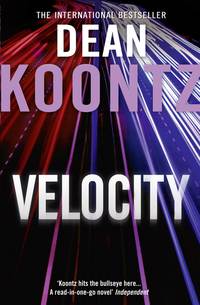

Velocity

At 11:45, after patting his hands dry on a dishtowel, he got a cold Guinness and drank it from the bottle. He finished it too fast.

Five minutes after the first beer, he opened a second. He poured it in a glass to encourage himself to sip it and make it last.

He stood with the Guinness in front of the wall clock.

Eleven-fifty. Countdown.

As much as Billy wanted to lie to himself, he couldn’t be fooled. He had made a choice, all right. The choice is yours. Even inaction is a choice.

The mother who had two children—she wouldn’t die tonight. If the homicidal freak kept his end of the bargain, the mother would sleep the night and see the dawn.

Billy was part of it now. He could deny, he could run, he could leave his window shades down for the rest of his life and cross the line from recluse to hermit, but he could not escape the fundamental fact that he was part of it.

The killer had offered him a partnership. He had wanted no part of it. But now it turned out to be like one of those business deals, one of those aggressive stock offers, that writers in the financial pages called a hostile takeover.

He finished the second Guinness as midnight arrived. He wanted a third. And a fourth.

He told himself he needed to keep a clear head. He asked himself why, and he had no credible answer.

His part of the business was done for the night. He had made the choice. The freak would do the deed.

Nothing more would happen tonight, except that without the beer, Billy wouldn’t be able to sleep. He might find himself carving again.

His hands ached. Not from his three insignificant wounds. From having clutched the tools too tightly. From having held the chunk of oak in a death grip.

Without sleep, he wouldn’t be ready for the day ahead. With morning would come news of another corpse. He would learn whom he had chosen for death.

Billy put his glass in the sink. He didn’t need a glass anymore because he didn’t care about making the beer last. Each bottle was a punch, and he wanted nothing more than to knock himself out.

He took a third beer to the living room and sat in his recliner. He drank in the dark.

Emotional fatigue can be as debilitating as physical exhaustion. All strength had fled him.

At 1:44, the telephone woke him. He flew up from the chair as if from a catapult. The empty beer bottle rolled across the floor.

Hoping to hear Lanny, he snared the handset from the kitchen phone on the fourth ring. “Hello” earned no reply.

The listener. The freak.

Billy knew from experience that a strategy of silence would get him nowhere. “What do you want from me? Why me?”

The caller did not respond.

“I’m not going to play your game,” Billy said, but that was lame because they both knew that he had already been co-opted.

He would have been pleased if the killer had replied with even a soft laugh of derision, but he got nothing.

“You’re sick, you’re twisted.” When that didn’t inspire a response, Billy added, “You’re human debris.”

He thought he sounded weak and ineffective, and for the times in which he lived, the insults were far from inflammatory. Some heavy-metal rock band probably called itself Sick and Twisted, and surely another was named Human Debris.

The freak would not be baited. He disconnected.

Billy hung up and realized that his hands were trembling. His palms were damp, too, and he blotted them on his shirt.

He was struck by a thought that should have but hadn’t occurred to him when the killer had called the previous night. He returned to the phone, picked up the handset, listened to the dial tone for a moment, and then keyed in *69, instigating an automatic call-back.

At the farther end of the line, the phone rang, rang, rang, but nobody answered it.

The number in the digital display on Billy’s phone, however, was familiar to him. It was Lanny’s.

10

Graceful in starlight with oaks, the church stood along the main highway, a quarter of a mile from the turnoff to Lanny Olsen’s house.

Billy drove to the southwest corner of the parking lot. Under the cloaking gloom of a massive California live oak, he doused the headlights and switched off the engine.

Picturesque chalk-white stucco walls with decorative buttresses rose to burnt-orange tile roofs. In a belfry niche stood a statue of the Holy Mother with her arms open to welcome suffering humanity.

Here, every baptized baby would seem to be a potential saint. Here, every marriage would appear to have the promise of lifelong happiness regardless of the natures of the bride and groom.

Billy had a gun, of course.

Although it was an old weapon, not one of recent purchase, it remained in working order. He had cleaned and stored it properly.

Packed away with the revolver had been a box of .38 cartridges. They showed no signs of corrosion.

When he had taken the weapon from its storage case, it felt heavier than he remembered. Now as he picked it off the passenger’s seat, it still felt heavy.

This particular Smith & Wesson tipped the scale at only thirty-six ounces, but maybe the extra weight that he felt was its history.

He got out of the Explorer and locked the doors.

A lone car passed on the highway. The side-wash of the headlights reached no closer than thirty yards from Billy.

The rectory lay on the farther side of the church. Even if the priest was an insomniac, he would not have heard the SUV.

Billy walked farther under the oak, out from its canopy, into a meadow. Wild grass rose to his knees.

In the spring, cascades of poppies had spilled down this sloped field, as orange-red as a lava flow. They were dead now, and gone.

He halted to let his eyes grow accustomed to the moonless dark.

Motionless, he listened. The air was still. No traffic moved on the distant highway. His presence had silenced the cicadas and the toads. He could almost hear the stars.

Confident of his dark-adapted vision though of nothing else, he set out across the gently rising meadow, angling toward the fissured and potholed blacktop lane that led to Lanny Olsen’s place.

He worried about rattlesnakes. On summer nights as warm as this, they hunted field mice and younger rabbits. Unbitten, he reached the lane and turned uphill, passing two houses, both dark and silent.

At the second house, a dog ran loose in the fenced yard. It did not bark, but raced back and forth along the high pickets, whimpering for Billy’s attention.

Lanny’s place lay a third of a mile past the house with the dog. At every window, light of one quality or another fired the glass or gilded the curtains.

In the yard, Billy crouched beside a plum tree. He could see the west face of the house, which was the front, and the north flank.

The possibility existed that this entire thing had in fact been a hoax and that Lanny was the hoaxer.

Billy did not know for a fact that a blond schoolteacher had been murdered in the city of Napa. He had taken Lanny’s word for it.

He had not seen a report of the homicide in the newspaper. The killing supposedly had been discovered too late in the day to make the most recent edition. Besides, he rarely read a newspaper.

Likewise, he never watched TV. Occasionally he listened for weather reports on the radio, while driving, but mostly he relied on a CD player loaded with zydeco or Western swing.

A cartoonist might be expected also to be a prankster. The funny streak in Lanny had been repressed for so long, however, that it was less of a streak than a thread. He made reasonably good company, but he wasn’t a load of laughs.

Billy didn’t intend to wager his life—or a nickel—that Lanny Olsen had hoaxed him.

He remembered how sweaty and anxious and distressed his friend had been in the tavern parking lot, the previous evening. In Lanny, what you saw was what he was. If he’d wanted to be an actor instead of a cartoonist, and if his mother had never gotten cancer, he would still have wound up as a cop with a problematic ten card.

After studying the place, certain that no one was watching from a window, Billy crossed the lawn, passed the front porch, and had a look at the south flank of the house. There, too, every window glowed softly.

He circled to the rear, staying at a distance, and saw that the back door stood open. A wedge of light lay like a carpet on the dark porch floor, welcoming visitors across the kitchen threshold.

An invitation this bold seemed to suggest a trap.

Billy expected to find Lanny Olsen dead inside.

If you don’t go to the police and get them involved, I will kill an unmarried man who won’t much be missed by the world.

Lanny’s funeral would not be attended by thousands of mourners, perhaps not even by as many as a hundred, though some would miss him. Not the world, but some.

When Billy had made his choice to spare the mother of two, he had not realized that he had doomed Lanny.

If he had known, perhaps he would have made a different choice. Choosing the death of a friend would be harder than dropping the dime on a nameless stranger. Even if the stranger was a mother of two.

He didn’t want to think about that.

Toward the end of the backyard stood the stump of a diseased oak that had been cut down long ago. Four feet across, two feet high.

On the east side of the stump was a hole worn by weather and rot. In the hole had been tucked a One Zip plastic bag. The bag contained a spare house key.

After retrieving the key, Billy circled cautiously to the front of the house. He returned to the concealment of the plum tree.

No one had turned off any lights. No face could be seen at any window; and none of the curtains moved suspiciously.

A part of him wanted to phone 911, get help here fast, and spill the story. He suspected that would be a reckless move.

He didn’t understand the rules of this bizarre game and could not know how the killer defined winning. Perhaps the freak would find it amusing to frame an innocent bartender for both murders.

Billy had survived being a suspect once. The experience reshaped him. Profoundly.

He would resist being reshaped again. He had lost too much of himself the first time.

He left the cover of the plum tree. He quietly climbed the front-porch steps and went directly to the door.

The key worked. The hardware didn’t rattle; the hinges didn’t squeak, and the door opened silently.

11

This Victorian house had a Victorian foyer with a dark wood floor. A wood-paneled hall led toward the back of the house, and a staircase offered the upstairs.

On one wall had been taped an eight-by-ten sheet of paper on which had been drawn a hand. It looked like Mickey Mouse’s hand: a plump thumb, three fingers, and a wrist roll suggestive of a glove.

Two fingers were folded back against the palm. The thumb and forefinger formed a cocked gun that pointed to the stairs.

Billy got the message, all right, but he chose to ignore it for the time being.

He left the front door open in case he needed to make a quick exit.

Holding the revolver with the muzzle pointed at the ceiling, he stepped through an archway to the left of the foyer. The living room looked as it had when Mrs. Olsen had been alive, ten years ago. Lanny didn’t use it much.

The same was true of the dining room. Lanny ate most of his meals in the kitchen or in the den while watching TV.

In the hallway, taped to the wall, another cartoon hand pointed toward the foyer and the stairs, opposite from the direction in which he was proceeding.

Although the TV was dark in the den, flames fluttered in the gas-log fireplace, and in a bed of faux ashes, false embers glowed as if real.

On the kitchen table stood a bottle of Bacardi, a double-liter plastic jug of Coca-Cola, and an ice bucket. On a plate beside the Coke gleamed a small knife with a serrated blade and a lime from which a few slices had been carved.

Beside the plate stood a tall, sweating glass half full of a dark concoction. In the glass floated a slice of lime and a few thin slivers of melting ice.

After stealing the killer’s first note from Billy’s kitchen and destroying it with the second to save his job and his hope of a pension, Lanny had tried to drown his guilt with a series of rum and Cokes.

If the jug of Coca-Cola and the bottle of Bacardi had been full when he sat down to the task, he had made considerable progress toward a state of drunkenness sufficient to shroud memory and numb the conscience until morning.

The pantry door was closed. Although Billy doubted that the freak lurked in there among the canned goods, he wouldn’t feel comfortable turning his back on it until he investigated.

With his right arm tucked close to his side and the revolver aimed in front of him, he turned the knob fast and pulled the door with his left hand. No one waited in the pantry.

From a kitchen drawer, Billy removed a clean dishtowel. After wiping the metal drawer-pull and the knob on the pantry door, he tucked one end of the cloth under his belt and let it hang from his side in the manner of a bar rag.

On a counter near the cooktop lay Lanny’s wallet, car keys, pocket change, and cell phone. Here, too, was his 9-mm service pistol with the Wilson Combat holster in which he carried it.

Billy picked up the cell phone, switched it on, and summoned voice mail. The only message in storage was the one that he himself had left for Lanny earlier in the evening.

This is Billy. I’m at home. What the hell? What’ve you done? Call me now.

After listening to his own voice, he deleted the message.

Maybe that was a mistake, but he didn’t see any way that it could prove his innocence. On the contrary, it would establish that he had expected to see Lanny during the evening just past and that he had been angry with him.

Which would make him a suspect.

He had brooded about the voice mail during the drive to the church parking lot and during the walk through the meadow. Deleting it seemed the wisest course if he found what he expected to find on the second floor.

He switched off the cell phone and used the dishtowel to wipe it clean of prints. He returned it to the counter where he had found it.

If someone had been watching right then, he would have figured Billy for a calm, cool piece of work. In truth, he was half sick with dread and anxiety.

An observer might also have thought that Billy, judging by his meticulous attention to detail, had covered up crimes before. That wasn’t the case, but brutal experience had sharpened his imagination and had taught him the dangers of circumstantial evidence.

An hour previously, at 1:44, the killer had rung Billy from this house. The phone company would have a record of that brief call.

Perhaps the police would think it proved Billy couldn’t have been here at the time of the murder.

More likely, they would suspect that Billy himself had placed the call to an accomplice at his house for the misguided purpose of trying to establish his presence elsewhere at the time of the murder.

Cops always suspected the worst of everyone. Their experience had taught them to do so.

At the moment, he couldn’t think of anything to be done about the phone-company records. He put it out of his mind.

More urgent matters required his attention. Like finding the corpse, if one existed.

He didn’t think he should waste time searching for the killer’s two notes. If they were still intact, he would most likely have found them on the table at which Lanny had been drinking or on the counter with his wallet, pocket change, and cell phone.

The flames in the den fireplace, on this warm summer night, led to a logical conclusion about the notes.

Taped to the side of a kitchen cabinet was a cartoon hand that pointed to the swinging door and the downstairs hallway.

At last Billy was willing to take direction, but a shrinking, anxious fear immobilized him.

Possession of a firearm and the will to use it did not give him sufficient courage to proceed at once. He did not expect to encounter the freak. In some ways the killer would have been less intimidating than what he did expect to find.

The bottle of rum tempted him. He had felt no effect from the three bottles of Guinness. His heart had been thundering for most of an hour, his metabolism racing.

For a man who was not much of a drinker, he’d recently had to remind himself of that fact often enough to suggest that a potential rummy lived inside him, yearning to be free.

The courage to proceed came from a fear of failing to proceed and from an acute awareness of the consequences of surrendering this hand of cards to the freak.

He left the kitchen and followed the hall to the foyer. At least the stairs were not dark; there was light here below, at the landing, and at the top.

Ascending, he did not bother calling Lanny’s name. He knew that he would receive no answer, and he doubted that he could have found his voice anyway.

12

Opening off the upper hallway were three bedrooms, a bathroom, and a closet. Four of those five doors were closed.

On both sides of the entrance to the master bedroom were cartoon hands pointing to that open door.

Reluctant to be herded, thinking of animals driven up a ramp at a slaughterhouse, Billy left the master bedroom for last. He first checked the hall bath. Then the closet and the two other bedrooms, in one of which Lanny kept a drawing table.

Using the dishtowel, he wiped all the doorknobs after he touched them.

With only the one space remaining to be searched, he stood in the hall, listening. No pin dropped.

Something had stuck in his throat, and he couldn’t swallow it. He couldn’t swallow it because it was no more real than the sliver of ice sliding down the small of his back.

He entered the master bedroom, where two lamps glowed.

The rose-patterned wallpaper chosen by Lanny’s mother had not been removed after she died and not even, a few years later, after Lanny moved out of his old room into this one. Age had darkened the background to a pleasing shade reminiscent of a light tea stain.

The bedspread had been one of Pearl Olsen’s favorites: rose in color overall, with embroidered flowers along the borders.

Often during Mrs. Olsen’s illness, following chemotherapy sessions, and after her debilitating radiation treatments, Billy had sat with her in this room. Sometimes he just talked to her or watched her sleep. Often he read to her.

She had liked swashbuckling adventure stories. Stories set during the Raj in India. Stories with geishas and samurai and Chinese warlords and Caribbean pirates.

Pearl was gone, and now so was Lanny. Dressed in his uniform, he sat in an armchair, legs propped on a footstool, but he was gone just the same.

He had been shot in the forehead.

Billy didn’t want to see this. He dreaded having this image in his memory. He wanted to leave.

Running, however, was not an option. It never had been, neither twenty years ago nor now, nor any time between. If he ran, he would be chased down and destroyed.

The hunt was on, and for reasons he didn’t understand, he was the ultimate game. Speed of flight would not save him. Speed never saved the fox. To escape the hounds and the hunters, the fox needed cunning and a taste for risk.

Billy didn’t feel like a fox. He felt like a rabbit, but he would not run like one.

The lack of blood on Lanny’s face, the lack of leakage from the wound suggested two things: that death had been instantaneous and that the back of his skull had been blown out.

No bloodstains or brain matter soiled the wallpaper behind the chair. Lanny had not been drilled as he sat there, had not been shot anywhere in this room.

As Billy had not found blood elsewhere in the house, he assumed that the killing occurred outside.

Perhaps Lanny had gotten up from the kitchen table, from his rum and Coke, half drunk or drunk, needing fresh air, and had stepped outside. Maybe he realized that his aim wouldn’t be neat enough for the bathroom and therefore went into the backyard to relieve himself.

The freak must have used a plastic tarp or something to move the corpse through the house without making a mess.

Even if the killer was strong, getting the dead man from the backyard to the master bedroom, considering the stairs, would have been a hard job. Hard and seemingly unnecessary.

To have done it, however, he must have had a reason that was important to him.

Lanny’s eyes were open. Both bulged slightly in their sockets. The left one was askew, as if he’d had a cast eye in life.

Pressure. For the instant during which the bullet had transited the brain, pressure inside the skull soared before being relieved.

A book-club novel lay in Lanny’s lap, a smaller and more cheaply produced volume than the handsome edition of the same title that had been available in bookstores. At least two hundred similar books were shelved at one end of the bedroom.

Billy could see the title, the author’s name, and the jacket illustration. The story was about a search for treasure and true love in the South Pacific.

A long time ago, he had read this novel to Pearl Olsen. She had liked it, but then she had liked them all.

Lanny’s slack right hand rested on the book. He appeared to have marked his place with a photograph, a small portion of which protruded from the pages.

The psychopath had arranged all of this. The tableau satisfied him and had emotional meaning to him, or it was a message—a riddle, a taunt.

Before disturbing the scene, Billy studied it. Nothing about it seemed compelling or clever, nothing that might have excited the murderer enough to motivate him to put forth such effort in its creation.

Billy mourned Lanny; but with a greater passion, he hated that Lanny had been afforded no dignity even in death. The freak dragged him around and staged him as if he were a mannequin, a doll, as if he had existed only for the creep’s amusement and manipulation.

Lanny had betrayed Billy; but that didn’t matter anymore. On the edge of the Dark, on the brink of the Void, few offenses were worth remembering. The only things worth recalling were the moments of friendship and laughter.

If they had been at odds on Lanny’s last day, they were on the same team now, with the same and singular adversary.

Billy thought he heard a noise in the hall.

Without hesitation, holding the revolver in both hands, he left the master bedroom, clearing the doorway fast, sweeping the .38 left to right, seeking a target. No one.

The bathroom, closet, and other bedroom doors were closed, as he had left them.

He didn’t feel a pressing need to search those rooms again. He might have heard nothing but an ordinary settling noise as the old house protested the weight of time, but it almost certainly had not been the sound of a door opening or closing.

He blotted the damp palm of his left hand on his shirt, switched the gun to it, blotted his right hand, returned the gun to it, and went to the head of the stairs.

From the lower floor, from the porch beyond the open front door, came nothing but a summer-night silence, a dead-of-night hush.

13

As he stood at the head of the stairs, listening, pain had begun to throb in Billy’s temples. He realized that his teeth were clenched tighter than the jaws of a vise.

He tried to relax and breathe through his mouth. He rolled his head from side to side, working the stiffening muscles of his neck.