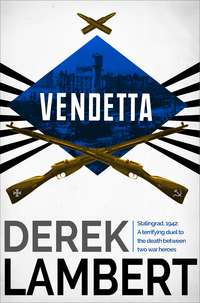

Vendetta

‘Keep it,’ Paulus said. ‘Read it later. Don’t worry, it’s very flattering. I understand from Berlin that most of the newspapers have picked up the story. You, Meister, are just the tonic the German people need. They’ve been reading too much lately about “heavy fighting”. They know by now what that means – a setback. And do you know what that makes you?’

‘No, Herr General.’

A shell exploded nearby. The cellar trembled, the lightbulb swung.

‘A diversionary tactic.’ Paulus pulled at one of his big ears and lit another cigarette. ‘A sideshow. But at the moment the German people don’t know about your co-star.’

‘Antonov?’ Meister’s throat tickled; it was a sniper’s nightmare to cough or sneeze as, target in the sights, he caressed the trigger of his rifle.

‘So far this rivalry – this feud within a battle – has been for local consumption. But not when you kill him.’

Meister cleared his throat but the tickle remained.

‘Then,’ Paulus said, ‘the whole Fatherland will know about Karl Meister’s greatest exploit. It will be symbolic, the victory of National Socialist over Bolshevism.’

The irritation scratched at Meister’s throat. Any minute now he would be racked with coughs.

Paulus unbuttoned the top pocket of his tunic. ‘I have a message for you. It’s from the Führer.’ Paulus read from a folded sheet of paper. ‘I have heard about the exploits of Karl Meister and I am profoundly moved by both his dedication and his expertise. I am led to understand that the Bolsheviks, having forcibly been made aware of Meister’s accomplishments, have produced a competitor. I confidently await your communiqué to the effect that Meister has disposed of him.’

Meister said: ‘Antonov is very good.’ He tried unsuccessfully to dislodge the irritation in his throat with one rasping cough.

‘But not as good as you?’

‘I’m not sure. He comes from the country, I come from a city, Hamburg. Maybe I have the edge, city sharpness … But he has instinct, a hunter’s instinct.’

Paulus said: ‘You are better. The Führer knows this,’ in a tone that was difficult to identify.

‘With respect, General Paulus,’ Meister said, ‘I think we are equal. I think he and I know that.’ He coughed again.

‘Know? You have some sort of communication?’

‘Respect,’ Meister said.

‘How many Russians have you killed?’

Meister who knew Paulus knew said: ‘Twenty-three. According to the Soviet propaganda Antonov has killed twenty-three Germans.’

Paulus said: ‘Do you want to kill him?’ and Meister, still trying to blunt the prickles in his throat, said: ‘Of course, because if I don’t he will kill me.’

‘Tell me, Meister, what makes you so different? What makes a sniper? A good eye, a steady hand … thousands of men have these qualifications.’

‘Anticipation, Herr General.’ Meister wasn’t sure. A flash of sunlight on metal, a fall of earth, a crack of a breaking twig … such things helped but there was more, much more. You had to know your adversary.

‘And Antonov has this same quality?’

‘Without a doubt. That’s what makes him so good.’

He saw Antonov and himself as skeletons stripped of predictability. Anticipating anticipation.

He began to cough. The sharp coughs sounded theatrical but he couldn’t control them. He heard Paulus say: ‘I hope you don’t cough like that when you’ve got Antonov in your sights. Are you sick?’ when he had finished.

‘Just nerves,’ Meister said.

Losing interest in the cough, Paulus, leaning forward, said: ‘So, what are your impressions of the battle, young man?’

Handling his words with care, Meister told Paulus that he hadn’t expected the fighting to be so prolonged, so concentrated.

Paulus, speaking so softly that Meister could barely hear him, said: ‘Nor did I.’ He stared at the arrows on the maps. ‘Do you have any theories about the name of this Godforsaken place?’

‘Stalingrad? I’ve heard that Stalin is determined not to lose the city named after him.’

‘Stalin was here in 1918,’ Paulus said. ‘During the Civil War when it was called Tsaritsyn. The Bolsheviks sent the White Guards packing just about now, October. Stalin took a lot of the credit for it.’ Paulus leaned back from his maps. ‘Have you heard anyone suggest that the Führer is determined to capture Stalingrad because of its name?’

‘No, Herr General,’ Meister lied. He had but he didn’t believe it.

Paulus asked: ‘Have you ever considered the possibility of defeat, Meister?’

‘Never.’

‘Good.’ With one finger Paulus deployed his troops on the smaller of the two maps. ‘We didn’t expect the Russians to fight so fanatically.’ He seemed to be thinking aloud. When he looked up his face was drained by his thoughts. He waved one hand. ‘Very well, Meister, you may go. Good luck.’

‘One question, Herr General?’

Paulus inclined his head.

‘Wouldn’t it be better if the people back home knew about Antonov now? It would be a better story, the rivalry between the two of us.’

‘They will,’ Paulus said.

‘Why not now?’

‘I should have thought that was obvious,’ Paulus said. ‘In case Antonov kills you first.’

Meister began to cough again.

CHAPTER THREE

At dawn on the following day Meister went looking for Antonov.

During the night, frost had crusted the mud, and rimed the ruins so that, with mist rising from the Volga, they had an air of permanency about them, relics from some medieval havoc. Among the relics soldiers roused themselves to continue the business of killing, moving lethargically like a yawning new day-shift. It was a time for snipers.

Lanz walked ahead of Meister, rifle in one hand, sketch map in the other, as they left the remains of the Central railway station where they had spent the night after the interview with Paulus. The prolonged meeting had made it unnecessary for Meister to even consider Lanz’s advice to stalk Antonov during the assault on Mamaev Hill: the attack had taken place and for the time being it was in German hands.

Lanz’s map supposedly indicated safe streets but in Stalingrad in October, 1942, there were no such thoroughfares: even now survivors of Rodimtsev’s tall guardsmen and Batyuk’s root-chewing Mongols lurked among the relics.

They turned into a street that had been lined with wooden houses. Although they had been destroyed in August when 600 German bombers had attacked the city killing, so it was said, more than 30,000 civilians, you could still smell fire. Corpses lying among the charred timber were crystallised with frost.

Lanz, who was slightly bow-legged, paused beneath a leafless plane tree and said: ‘What’s it like to have a personal minesweeper?’

‘What’s it like to have a personal marksman?’

But of the two of them Lanz was the true protector: Lanz took the broad view of battle, Meister viewed it through his sights. Meister thought that Lanz, peering from beneath his steel helmet, looked like a tortoise.

‘Time for breakfast?’ Lanz asked.

‘When we get to the square,’ mildly surprised to hear himself, a soldier as raw as a grazed knuckle, giving orders to a corporal.

The bullet smacked into the flaking trunk of the tree above Meister’s head. He and Lanz hit the ground.

After a few seconds Lanz said: ‘Antonov?’

‘Antonov wouldn’t have missed.’

Holding his rifle, a Karabiner 98K fitted with a ZF 41 telescopic sight, Meister edged behind the bole of the tree to wait for the second shot.

The marksman, amateurish or, perhaps, wounded, was firing from the wreckage of a wooden church across the street. The fallen dome lay in the nave, a giant mushroom.

Meister, peering through his sights, looked for the sniper’s cover. If I were him … the altar just visible past the dome. He steadied the rifle, disciplined his breathing, took first pressure on the trigger.

River-smelling mist drifted along the street but it was thinning.

The second shot spat frozen mud into Lanz’s face. The marksman, whose fur hat had risen in Meister’s sights, reared and fell behind the altar.

‘Twenty-four,’ Lanz said.

They ate breakfast in a cellar in Ninth of January Square where in September Sergeant Pavlov and sixty men barricaded in a tall house had held up the German tanks for a week.

They ate bread and cheese and drank ersatz coffee handed over reluctantly by a group of soldiers when Lanz showed them a chit signed by the commanding officer of the 3rd Battalion, 194th Infantry Regiment, to which Meister was attached.

The infantrymen looked very young and they were trying to look tough; instead they looked bewildered and Meister felt much older and decided that it was his singleness of purpose, his detachment from the overall battle, that made this so.

One of them, eighteen or so with smooth cheeks and soft stubble on his chin, said: ‘So you’re Meister. What makes you tick?’ his accent Bavarian, and another, leaner faced, with a northern intonation: ‘They say you’ve killed 23 Ivans. True, or is it propaganda?’

Lanz answered him. ‘Correction. Twenty-four. He just killed one round the corner,’ making it sound as though Meister had won a game of skat.

‘I don’t know what makes me tick,’ Meister said to the Bavarian.

‘Do you enjoy killing Russians?’

‘I do my job.’

‘What sort of answer is that?’

‘Do you enjoy what you’re doing?’

‘Are you crazy?’ the northerner asked. ‘Before I came to Russia I’d never even heard of Stalingrad. It’s like fighting on the moon.’

Meister drank some bitter coffee. His mother had made beautiful coffee and in the mornings its breakfast smell had reached his bedroom and when he had opened his window he had smelled pastries from the elegant patisserie next door, a refreshing change from the smell of perfume from his father’s factory that permeated the elegant house in Hamburg.

‘What’s it like being a hero?’ the Bavarian asked.

‘Great,’ Lanz answered.

‘I suppose you’ll get an Iron Cross if you kill Antonov,’ the Bavarian said ignoring Lanz. ‘And a commission and a reception in the Adlon Hotel in Berlin.’

If kill him,’ Meister said. ‘But in any case I don’t want any of those things,’ and Lanz said: ‘How do you know about the Adlon?’

‘I’ve been around,’ the Bavarian said. He produced a looted bottle of vodka from his tunic and poured some down his throat. ‘Great stuff. Better than schnapps.’ He choked and turned away.

‘Come on,’ Lanz said to Meister, ‘move yourself – you’ve got an appointment with Comrade Antonov.’

‘Look out for mines,’ the northerner warned them. ‘We’ve been using dogs to explode them. The lieutenant lost his Dobermann that way. Where are you going anyway?’

‘Mamaev Hill,’ Meister told him.

‘Shit. Are you sure it’s ours? It could have changed hands again – the Russians shipped a lot of troops across the river in the mist.’

‘Then Antonov will be early for his appointment,’ Lanz said.

***

By 10 am the frost had melted and the mist had lifted and galleons of white cloud sailed serenely in the autumn-blue sky above Mamaev Hill which was still in German hands.

From a shell-hole on the hill, once a Tartar burial ground, more recently a picnic area, now a burial ground again, Meister could see the industrial north of Stalingrad and, to the south, the commercial and residential quarter. And he could make out the shape of the city, a knotted rope, twenty or more miles long, braiding this, the west bank of the Volga. It was rumoured that the German High Command hadn’t anticipated such an elastic sprawl; nor, it was said, had they envisaged such a breadth of water, splintered with islands and creeks.

Through his field-glasses he could see the Russian heavy artillery and the eight and twelve-barrelled Katyusha launchers spiking the fields and scrub pine on the far bank. He scanned the river, clear today of timber and bodies because, although they had used flares, the German gunners hadn’t been able to see the Russian relief ships in the mist-choked night.

Where was Antonov?

Meister swung the field-glasses to the north where only factory chimneys remained intact, fingers prodding the sky. He wouldn’t be there: snipers don’t prosper in hand-to-hand fighting.

He looked south. To the remnants of the State Bank, the brewery, the House of Specialists, Gorki Theatre. No, Antonov would be nearer to the hill than that, moving cautiously towards Mamaev, Stalingrad’s principal vantage point. Scanning it with his field-glasses …

Meister shrank into the shell-hole. Lanz handed him pale coffee in a battered mess tin. ‘Where is he?’

‘Down there.’ Meister pointed towards the river bank. ‘Somewhere near Crossing 62. In No Man’s Land.’

‘Will you be able to get a shot at him?’

‘Not a chance. He won’t show himself, not while I’m up here.’

‘He knows you’re here?’

‘He would be up here if the Russians still held Mamaev. It’s the only place where you can see how the battle’s going. Who’s holding the vantage points.’

‘You’ll be a general one day,’ Lanz said.

‘I wanted to be an architect.’

‘I want to rob the Reichsbank. Instead I became a nanny.’

Meister, who was never quite sure how to handle Lanz in this mood, drank the rest of his foul coffee. It was said to be made from acorns and dandelion roots and there was no reason to contest this.

Lanz lay back on the sloping bank of the crater, lit a cigarette and said: ‘How long is this going to last?’ words emerging in small billows of smoke.

‘Antonov and me? God knows. It’s been official for three days thanks to Red Star.’

If the Soviet army newspaper hadn’t matched Antonov against him the duel would never have started.

A Yak, red stars blood-bright on its tail and fuselage, flew low overhead. The Germans held the two airfields, Gumrak and Pitomik, but the Russians held the whole of Siberia. They could retreat forever, Meister thought.

‘I wish to hell it was over,’ Lanz said.

‘One way or the other?’

Lanz, smoking hungrily, didn’t reply.

Meister thought: ‘What would I be doing now if I were Antonov?’ and knew immediately. He would be checking whether any Russians had been killed today by a single marksman’s shot.

Could he find out about the sniper who had died at the altar near Ninth of January Square? Russians isolated in pockets of resistance were often in radio contact with Red Army headquarters.

Yes, it was possible.

CHAPTER FOUR

Yury Antonov, waiting for Razin to return from a command post, dozed in a tunnel leading to the river.

He saw sunflowers with blossoms like smiling suns crayoned by children and he heard the insect buzz from the taiga shouldering the wheatfields and he smelled the red polish that his mother used in the wooden cottage.

It had been a languorous Sunday early in September when they had come for him. He had been lying fully clothed on his bed picturing the naked breasts of a girl named Tasya who lived in the next village. His younger brother, Alexander, was sitting on the verandah drinking tea with his father and his mother was in the kitchen feeding the bowl of borsch bubbling on the stove.

After a Komsomol meeting the previous evening he had walked Tasya home. He had kissed her awkwardly, feeling the gentle thrust of her breasts against his chest, and ever since had been perturbed by the intrusion of lascivious images into the purity of his love.

He was almost eighteen, exempt from military service because of a heart murmur triggered by rheumatic fever, and she was seventeen. He was worried that, like other girls, she might be intoxicated by the glamour of the other young men departing to fight the Germans. A farm labourer wasn’t that much of a catch. But at least he was here to stay.

He considered the contents of his room. A small hunting trophy, the glass-eyed head of a lynx, on the wall beside a poster of a tank crushing another tank adorned with a Hitler moustache – he dutifully collected anti-Nazi memorabilia but here on the steppe the war seemed very far way – his rifle, a red Young Pioneer scarf from his younger days, a book of Konstantin Simenov’s poems … Yury himself often conceived luminous phrases but he could never utter them.

He heard a car draw up outside. A tractor was commonplace, a car an event. He peered through the lace curtains. A punished black Zil coated with dust. Two men were climbing out, an Army officer in a brown uniform and a civilian in a grey jacket and open-neck white shirt. Fear stirred inside Yury, although he couldn’t imagine why.

His father called from the verandah: ‘Yury, you’ve got visitors.’ Yury could hear the apprehension in his voice. He changed into a dark blue shirt, slicked his hair with water and went outside.

They were sitting on the rickety chairs beside the wooden table drinking tea. The officer was a colonel; he had a bald head, startling eyebrows and a humorous mouth. The civilian had dishevelled features and pointed ears; he popped a cube of sugar into his mouth and sucked his tea through it. Alexander was walking towards the silver birch trees at the end of the vegetable garden.

The colonel said: ‘I’m from Stalingrad, Comrade Pokrovsky is from Moscow. Have you ever been to Moscow, Yury?’

Yury shook his head. He wondered if Pokrovsky was NKVD.

‘Or Stalingrad?’

‘No, Comrade colonel.’

‘Ah, you Siberians. You’re very insular – if that’s the right word for more than 4 million square miles of the Soviet Union. What’s the farthest you’ve been from home?’

‘I’ve been to Novosibirsk,’ Yury told him.

‘Novosibirsk! Forty miles from here. Well, I have news for you Yury. You’re going farther afield. To Akhtubinsk, eighty miles east of Stalingrad. Please explain, Comrade Pokrovsky.’

The civilian swallowed the dissolved sugar and said to Yury: ‘You are going to serve your country. God knows, you might even become a Hero of the Soviet Union.’

Yury’s father interrupted. ‘He has a bad heart. I have the documents …’ The weathered lines on his face took on angles of worry.

‘Heart condition? According to my information he has a heart murmur. A murmur, comrade! What is a murmur when Russia cries out in anguish?’

The colonel said to Yury’s father: ‘Of course I realise that farm work is just as important as military service,’ and Pokrovsky said: ‘Not that there seems to be much work going on round here. Haven’t you heard about the war effort?’

‘We’ve just finished harvesting one crop. Tomorrow we start on the wheat.’ He spoke with dignity, pointing at the golden fields stroked by a breeze.

‘You Siberians,’ the colonel remarked. ‘You don’t stay on the defensive long, do you? Ask the Germans, you’ve taught them a lesson or two.’

Yury, his emotions competing – apprehension complicated by faint arousal of bravado – waited to find out what the two men wanted.

Pokrovsky spoke. ‘Siberians? Very courageous.’ He stroked one crumpled cheek. ‘But don’t forget the glorious example given by the Muscovites. And by Comrade Stalin. Did you read his speech on November 7th last year?’ Pokrovsky looked quizzically at Yury.

Yury tried to remember some dashing phrase from the speech on the 24th anniversary of the Revolution. It had certainly been a stirring address.

Pokrovsky said: ‘I was in Red Square when he spoke. What a setting. Troops massed in front of the Kremlin, German and Russian guns rumbling forty miles away and Stalin, The Boss, inspired.’

His voice was curiously flat for such an evocation. Then he began to quote. ‘“Comrades, Red Army and Red Navy men, officers and political workers, men and women partisans! The whole world is looking upon you as the power capable of destroying the German robber hordes! The enslaved peoples of Europe are looking upon you as their liberators … Be worthy of this great mission.’”

Yury imagined the little man with the bushy moustache standing on Lenin’s tomb. Heard his Georgian accents on a breeze stealing through the Urals.

“‘… Death to the German Invaders. Long live our glorious country, its freedom and independence. Under the banner of Lenin – onward to victory.’”

Without changing his tone, Pokrovsky said: ‘Do you believe in those qualities, Yury? Freedom for instance?’

‘Of course,’ Yury replied, surprised.

‘Of course, he’s a Siberian,’ said the colonel who was apparently obsessed with their matchless qualities.

Pokrovsky seemed satisfied. ‘As you may have guessed it is your abilities as a hunter that interest us. I understand you’re the best shot in the Novosibirsk oblast?’

‘Second best,’ Yury said promptly. ‘My father is the champion.’

His father took off his black peaked cap and rotated it slowly on his lap.

‘But a little too old to fight, eh?’ The colonel smiled, offering commiseration.

As the sun reached inside the verandah through the fretted eaves steam rose from the dew-soaked floorboards. A tractor clattered lazily in the distance.

Pokrovsky said: ‘There are ten of you. The best shots in the Soviet Union. You will all be reporting to Akhtubinsk. There will be a competition.’

He paused. He enjoyed effect. The colonel took over and Yury sensed that there was little harmony between the two of them. As he talked creases on his forehead pushed at the baldness above them.

‘The other nine are Red Army. Marksmen. But you apparently are exceptional. Your prowess reached the ears of the military commander of the area and he told us about you.’

Yury’s mother peered from the doorway. She was smoothing her dress, printed with blue cornflowers, and her plump features were anxious.

Her husband waved her away. ‘You will forgive me, comrades,’ he said in a tone that didn’t seek forgiveness, ‘but would you please tell me what this is all about?’

Pokrovsky popped another lump of sugar into his mouth. He seemed to be debating with himself. Finally he said: ‘As you know, the Germans attacked Stalingrad last month. The battle is still being fought fiercely and I have no doubt we shall win. But the Germans have introduced a new tactic …’

The colonel explained: ‘The Germans are very good at propaganda. They know we are going to win the Battle of Stalingrad’ – he didn’t sound quite as convinced as Pokrovsky – ‘and so they have to find a hero to bolster their faith. Well, they’ve found one. His name is Meister and he’s a sniper. The best. Ten Russians killed, each with one bullet, in one week. Very soon the German people will be hearing about this young Aryan warrior with eyes like a hawk.’ The colonel smiled. ‘We have to beat the propagandists to the draw.’

Emotions not entirely unpleasant expanded inside Yury. ‘But surely these other marksmen from the Red Army are better than me?’

‘That,’ Pokrovsky said, standing up, ‘is what we are going to find out at Akhtubinsk. Come, pack your things, we haven’t much time.’

Yury’s father said: ‘Do you have any authority, any papers?’

‘Authority?’ Pokrovsky spun out another pause. Then: ‘Oh, we have authority all right. From the Kremlin. After all, the duel will be fought in the City of Stalin.’

***

A rat ran past Antonov, pausing at the mouth of the tunnel, a disused sewer, before jumping into the mud-grey waters of the Volga to swim to the east bank where there was still plenty of food. Antonov doubted whether it would make it: the Red Army had trouble enough getting across.

Where was Razin?

He shivered. The wet-cold of the tunnel had none of yesterday’s expectancy about it. Antonov yearned for snow, but according to the locals – there were said to be 30,000 still on the west bank – it wouldn’t settle until November.

These people professed to dread winter. Antonov suspected that, like Siberians, they deluded themselves. Summer was merely a ripening: winter was truth – the steppe, white and sweet, cold and lonely, animal tracks leading you into the muffled taiga, the song of cross-country skis on polished snow, blue-bright days with ice dust sparkling on the air, and in the evenings kerosene lamps and a glowing stove beckoning you home.