Paper: An Elegy

Meanwhile, in the giant paper mills, the machines grind on, the woodchips stewing in their alkali solutions, and the top-secret pulp recipes crying out like addicts at a meth clinic for their chemical additives. A recent Handbook of Toxicology and Ecotoxicology for the Pulp and Paper Industry (2001) lists more than thirty common compounds that are used to make paper: acrylamide monomer; alkenyl succinic anhydride; alkyl ketene dimer wax dispersant; aluminium sulphate; aniline green dye; anionic polyurethane; azo dye anionic; azo dye cationic; bentonite; bronopol-type biocide; calcium polyacrylamide; cationic starch; chlorine; colloidal silica sol; defoamer; fluorescent whitening agents; hydrochloric acid; hydrogen peroxide; N-methylisothiazolinone-type biocide; polyaluminium hydroxide chloride; polyamide amine epichlorohydrin resin; polyamine; polyethylenimine; rosin size dispersant; sodium chlorate; sodium dithionite; sodium hydroxide; sodium silicate; stearic acid; and styrene/acrylate copolymer. These are the chemicals and dyes that give paper the strength and the whiteness we so admire and desire. They are applied in two ways: either blended with the stock, to fill and load the space between the wood-pulp cellulose fibres, laid down like fatty-tissue deposits or little Botox-boosts; or sprayed and applied as coatings, like permatan, or varnish. When you pick up a book – when you hold a piece of paper – what you have in your hand is no natural product, no emanation of mind. It is the product of two thousand years of continual beating, dipping and drying. It is a testament to human industry and ingenuity – a miracle of inscrutable intricacy.

Hand-made fibrous paper incorporating leaves

Like poor blind Oedipus, my fate was sealed long ago, but I have only now solved the riddle, have only now found the path. In the late 1970s and early 1980s even the most non-selective and non-academic of secondary schools in England began offering a kind of rudimentary careers advice to pupils. At the end of the fifth year we were invited to meet with a teacher – let’s call him Tiresias – who had been entrusted with running the new-fangled punched-card careers guidance system. We had to answer various questions, and the cards on which our answers had been entered were fed into the school’s computer – an Oracle? – which eventually delivered its verdict on a till-type print-out. And so we children of Essex were taught to aim for careers as secretaries, receptionists, cabbies and mechanics. I was lucky. My destiny, apparently, was to work in forestry. Youth Training Schemes were available.

Thirty years later, and having barely set foot in a forest since, except for the occasional hike and adventure in Epping Forest, and in the fictional woods and groves of Greek myth and Arthurian Romance, as well as in the Hundred Acre Wood, and Where the Wild Things Are and The Gruffalo, I realise that I am in fact up to my neck in the leafy depths, drowning in the loam. Not a forester, but certainly a child of the forest, a denizen of the dusky dells and ferny floors. Wood is my fuel: this morning alone I came home with two reams of copier paper, two Silvine reporter’s notebooks, some gummed envelopes, five HB pencils, a Belfast Telegraph, a Daily Telegraph, a Guardian, The Times, a Daily Mail, The World of Interiors and Boxing Monthly. And I’d only gone into the shop for some stamps. I consume more paper, pound for pound, than any other product, food included. I am a paper omnivore. I devour it: any kind, from anywhere. (Or almost anywhere: in London recently I wandered absentmindedly into Smythson, the high-class stationers on Bond Street, one of those shops where the staff are even better-looking than the customers, who are anyway better-looking than anyone you’ve ever met, and where there are security guards on the door, and where a nice brown leather stationery bureau will set you back £1,500, and where the notebooks can be gold-embossed with lettering of your choice, and where, realistically, I couldn’t even afford a pack of cedar pencils.)

And of course, when I scribble and print on my piles and piles of virgin white paper with my Faber-Castell pencils and my decidedly non-state-of-the-art Hewlett Packard scanner-copier-printer, what I’m really doing is taking a big double-headed felling axe and laying it unto the root. Now I am become Death, the destroyer of … woods. If a ream of paper is roughly equivalent to 5 per cent of a tree – though such figures are notoriously difficult to calculate and verify – then at approximately twenty reams’ worth of notes, or eight thousand sheets, the book you are currently holding in your hands is the product of at least one entire tree, though that’s not including all the paper books that were read and consumed in its production, nor the paper used for its own printing and publication: the gross product cost far exceeds the one tree, and is probably at least a small copse. The world’s great forests are not in Canada, Russia or the Amazon basin: they are in bookshops, bookshelves and Amazon warehouses all over the world.

As soon as one begins to investigate and explore how and why we have made trees into paper one finds oneself in deeply troubling Oedipus territory – ignorant, blind, doomed as a despoiler – or perhaps more like Dante at the beginning of the Inferno, ‘Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita/mi ritrovai per una selva oscura/che la diritta via era smarrita’ (‘In the middle of the journey of our life/I found myself in a dark forest,/where the straight way was lost’). The poet Ciaran Carson translates Dante’s famous ‘selva oscura’ as ‘gloomy wood’: in tracing the history of modern paper manufacturing, the gloom at times seems overwhelming and all-encompassing, like the sudden approach of night, or like Malcolm’s army advancing towards Dunsinane at the end of Macbeth, creeping up unsuspected, camouflaged by boughs cut from the Great Birnam wood (a scene brilliantly, darkly depicted in Kurosawa’s 1957 film adaptation of the play, Throne of Blood: see YouTube). Light turns first to shadow and then to inescapable dark.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, paper manufacturers began to search for new papermaking materials. There were simply not enough rags to go around: in 1800, Britain imported £200,000 worth of foreign rags for papermaking, and prices were rocketing. In the words of Dard Hunter, author of the unsurpassable Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft (1943), what was required was ‘a vegetable fibre in compact form, easily gathered and handled and furnishing the highest average yield per acre of growth’. Wood was the obvious answer, and a man named Matthias Koops – mapmaker, bankrupt and inventor – came up with a quick solution. In 1800

An example from G. F. Smith & Sons Ltd, paper and envelope makers, of the fibre content of their business envelopes (courtesy G. F. Smith & Sons Ltd)

Koops published the magnificently titled Historical Account of the Substances Which have been Used to Convey Ideas from the Earliest Date to the Invention of Paper, in which he claimed that some of the pages of the book were of ‘Paper made from wood alone, the product of this country, without any intermixture of rags, waste paper, bark, straw or any other vegetable substance, from which paper might be, or has hitherto been manufactured; and of this the most ample testimony can be given’.

Testimony was indeed forthcoming, for during 1800 and 1801 Koops was granted a number of patents for paper manufacturing, including one ‘for manufacturing paper from straw, hay, thistles, waste and refuse of hemp and flax, and different kinds of wood and bark’. Attracting investors to his alternative paper-manufacturing project, Koops built a vast paper mill in London, at Westminster – the grim sight of which the William Blake scholar Keri Davies believes may have influenced Blake’s apocalyptic vision of industrialisation in his prophetic book, The Four Zoas – but within a year Koops’s creditors had closed in on him again, and by 1804 the mill had been sold off, and it was left to others to profit from paper made from wood. These others included Friedrich Gottlob Keller, the German weaver who was granted the patent for a wood-grinding machine in 1840, a machine which was then developed by Heinrich Voelter and imported to America by Albrecht Pagenstecher, founder of the first ground-wood pulp mill in the United States. Chemical wood-pulping processes, which stew wood rather than grind it – using either alkali, in the soda process, or acid, in the sulphite process – were developed during the same period, and by the mid-nineteenth century the West’s potential paper crisis had been averted: raw-material costs had fallen, production had increased, demand worldwide exploded. The Age of Paper had truly begun. Wood had saved paper.

And paper, in turn, has destroyed wood. Today, almost half of all industrially felled wood is pulped for paper, and according to green campaigners our uncontrollable appetite for the white stuff has become a threat to the entire blue planet. In medieval Britain special courts and inquisitions were held to hear the ‘pleas of the forest’, with tenants and foresters being summoned for breaches of the forest laws, including damage to timber and the poaching of venison. In a contemporary reversal of these forest eyres, activists and campaigners now call upon multinational paper companies to account for their forest-management crimes.

One of the angriest and most eloquent among the modern-day forest pleaders is the writer and activist Mandy Haggith, who argues that ‘We need to unlearn our perception of a blank page as clean, safe and natural and see it for what it really is: chemically bleached tree-mash.’ According to Haggith and many others – groups such as ForestEthics, the Dogwood Alliance and the Natural Resources Defense Council – modern papermaking has had devastating human and environmental consequences: in short and in summary, as well as causing soil erosion, flooding, and the widespread extinction of habitats and species, it has also caused poverty, social conflict, and is leading us on a long and inexorable paper trail to world apocalypse, via self-destruction. The few giant global companies that dominate the paper industry – International Paper, Georgia-Pacific, Weyerhaeuser, Kimberly-Clark – are accused of razing ancient forests, replacing them with monoculture plantations that are dependent upon chemical-based fertilisers, and polluting rivers and lakes with their industrial by-products.

The charge sheet is long and complicated, but even if the paper companies could acquit themselves entirely, and wood resources were inexhaustible, and all forests forever sustainably managed, paper manufacturing would still pose a threat to the world’s future, because the mass industrial production processes use so many other finite resources, including water, minerals, metals and fuels. ‘Making a single sheet of A4 paper,’ according to Haggith, ‘not only causes as much greenhouse gas emissions as burning a lightbulb for an hour, it also uses a mugful of water.’ (Industry figures suggest that it takes about forty thousand litres of water to make a tonne of paper, though much of that water is recycled.) With our delicious, decadent daily diet of newspapers, magazines, Post-it notes, toilet and kitchen rolls, we are guzzling down gallons of water and eating up electricity: we have grown fat and become obese on paper. In the UK, average annual paper consumption per person is around two hundred kg; in America it’s closer to three hundred kg; and in Finland – whose paper industry accounts for 15 per cent of the world’s total production – it’s even more. Consumption in China is currently a mere fifty kg per person, but gaining fast. World paper consumption is now approaching a million tonnes per day – and most of this, after its short useful life, ends up in landfill. One way or another, and indisputably according to Haggith, ‘We treat paper with utter contempt.’

Which is odd, because we absolutely love trees. In fact, we worship them – not dendrologists, but dendrolators. In The Golden Bough (1890), that massive, mad compendium of myths and rituals, James Frazer has a whole chapter on the worship of trees, listing rituals for just about every human and non-human experience, from birth to marriage to death and rebirth, ad infinitum. The Golden Bough is of course itself named after the story from the Aeneid, in which Aeneas and the Sibyl are required to present a golden bough to Charon, in order to cross the river Styx and thus gain access, through Limbo and Tartarus, to the Elysian Fields, where Aeneas is reunited with his father, Anchises. Trees grant us access to underworlds and other worlds also in Norse mythology, with Yggdrasil, the World Tree, a giant ash which connects all the worlds, and from which Odin is sacrificed by being hanged, before being resurrected and granted the gift of divine sight. Stories of special, sacred and cosmic trees abound in religion, in history and in legend: Augustine is converted under a fig tree; Newton is inspired under an apple tree; the Buddha under the Bo tree; Wordsworth ‘under this dark sycamore’, composing ‘Tintern Abbey’; and in the eighteenth century a large elm tree in Boston, the so-called Liberty Tree, became the symbol of resistance to British rule over the American colonies.

If the tree is a site of personal enlightenment and a symbol of emancipation, then woods and forests are places of enchantment that can and often do represent entire peoples, nations, and indeed the world as a whole. In Andrew Marvell’s ‘Upon Appleton House, to my Lord Fairfax’ (1651), for example, often read as an allegory on the English Civil War, the narrator takes ‘sanctuary in the wood’, where ‘The arching boughs unite between/The columns of temple green’ – the wood as a place of safety where one can take stock, rethink and re-imagine. Similarly, in Italo Calvino’s fabulous novel The Baron in the Trees (1957), set in Liguria in the eighteenth century, the young Baron Cosimo Piovasco di Rondò climbs up into a tree in order to escape his tormenting family and to gain perspective on the world: he likes it so much up there that he decides to stay.

A yearning for arboreal existence is no mere fairytale – although it is also, often, a fairytale (the tales of the Brothers Grimm, for example, feature a veritable forest of forests, so much so that they might be said to grow not from German folktales but direct from German soil). An extraordinary number of recent books celebrate trees and woodlands in near mystical fashion. Colin Tudge, in The Secret Life of Trees: How They Live and Why They Matter (2005), argues that ‘without trees our species would not have come into being at all’. Richard Mabey, in Beechcombings: The Narratives of Trees (2007), sees trees as witnesses to human history, ‘dense with time’. And Roger Deakin, in Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees (2007), provides a personal account of how trees teach us about ourselves and each other, the forest not as a mirror to nature, but the mirror of nature. ‘I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately,’ proclaimed Thoreau, long ago, in Walden, Or Life in the Woods (1854), ‘to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.’

And here perhaps lies the source of our contemporary guilt and confusion about turning trees into paper; here is the heart of the sylvan darkness. It’s not that we can’t see the wood for the trees: we can’t even see the trees. When we gaze into the forest mirror we see ourselves. The anthropologist Maurice Bloch, in an article, ‘Why Trees, Too, are Good to Think With: Towards an Anthropology of the Meaning of Life’ (1998), argues that ‘the symbolic power of trees comes from the fact that they are good substitutes for humans’. Are we human? Or are we dryad? In the growth and maturation of a tree we are reminded of the growth and maturation of a person. In tree parts, for better and for worse, we see body parts: branches, limbs; leaves, hair; bark, skin; trunk, torso; sap, blood. Lavinia, in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, has her hands, ‘her two branches’, ‘loppd’ and ‘hew’d’; in his poem ‘Tree at my Window’, Robert Frost has Fate put man and tree together, ‘Your head so much concerned with outer/Mine with inner, weather’. Living trees clearly symbolise the regeneration and continuation of human life: the transformation of wood into paper is therefore a kind of self-annihilation, a diabolical transformation, the reverse of the transformation of the wine into the blood of Christ during Mass. Black Mass = white sheet. In one of the most extraordinary passages about tree worship in the whole of The Golden Bough, Frazer writes:

How serious the worship was in former times may be gathered from the ferocious penalty appointed by the old German laws for such as dared to peel the bark of a standing tree. The culprit’s navel was to be cut out and nailed to a part of the tree which he had peeled and he was to be driven round and round the tree until all his guts were wound around its trunk. The intention of the punishment clearly was to replace the dead bark by a living substitute; it was a life for a life, the life of a man for the life of a tree.

Such narratives and fantasies of punishment and self-punishment characterise much contemporary Western nature writing, which often reads like an experiment in narcissism, in that true sense of Narcissus being unable to distinguish between himself and his reflection. The theoretical branch of nature writing is a form of literary criticism called ecopoetics (from the Greek ‘oikos’, home or dwelling place, and ‘poiesis’, ‘making’), which wrestles with difficult issues of selfhood and self-sufficiency. According to Jonathan Bate, one of the most brilliant proponents of ecopoetics, ‘our inner ecology cannot be sustained without the health of ecosystems’. In his book The Song of the Earth (2000), a tour de force, or at least a tour de chant, Bate argues that ‘The dream of deep ecology will never be realized upon the earth, but our survival as a species may be dependent on our capacity to dream it in the work of our imagination.’ The means by which we might do this, according to Bate, borrowing his terms from the American poet Gary Snyder and the philosopher Paul Ricoeur, is to understand works of art as ‘imaginary states of nature, imaginary ideal ecosystems, and by reading them, by inhabiting them, we can start to imagine what it might be like to live differently upon the earth’. In a riddling conclusion to his book, Bate writes that ‘If mortals dwell in that they save the earth and if poetry is the original admission of dwelling, then poetry is the place where we save the earth.’

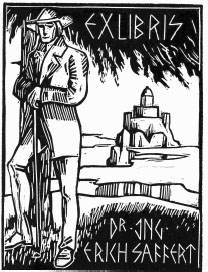

Book plate of Erich Saffert, Doctor of Agriculture and Forestry Surveying, Austria, early twentieth century (courtesy Sieglinde Robinson)

Bad news: poetry is probably not the place where we will save the earth. And there is probably little evidence either for Bate’s contention that ‘mortals dwell in that they save the earth’. Mortals dwell, rather – or certainly have dwelt – in that they use the earth, from the Romans and the Saxons clearing British woodland for developing iron-smelting works, to the development of Forstwissenschaft (forest science) in Germany, where algebra and geometry combined to produce a kind of mathematics of the forest, by which foresters could calculate volumes of wood and timber and therefore plan for felling and replanting. Ecopoetics yearns for oneness with the natural world, but all of our experience suggests that separation from nature – domination, despoliation – is the norm.

So how to continue in this difficult relationship? How to find our way through the gloom? How to dwell with forests and with paper? Might we perhaps restrict ourselves solely to rotefallen, or wyndfallen wood, so-called cablish (from the Latin ‘cableicium’, or ‘cablicium’), in order to provide ourselves with fuel and with fibre for our books? Should we all become little Thoreaus, building cabins from small white pines? Perhaps we should further investigate alternatives to wood pulp in paper production – alternatives which include sustainable crops such as hemp, straw, flax and kenaf? At the very least we should respect our paper – if nothing else, as a sign of respect for ourselves.

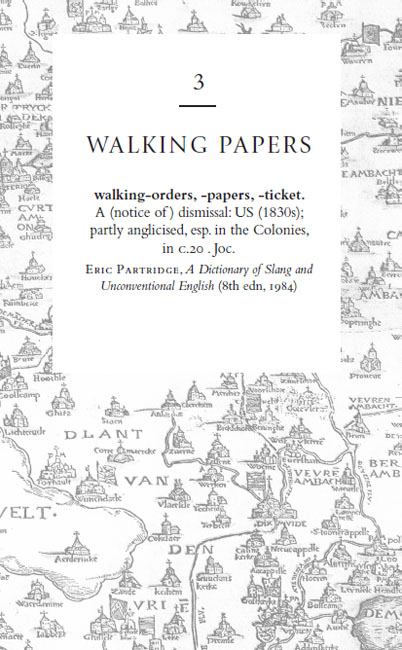

Woodcut map printed on paper, sixteenth century

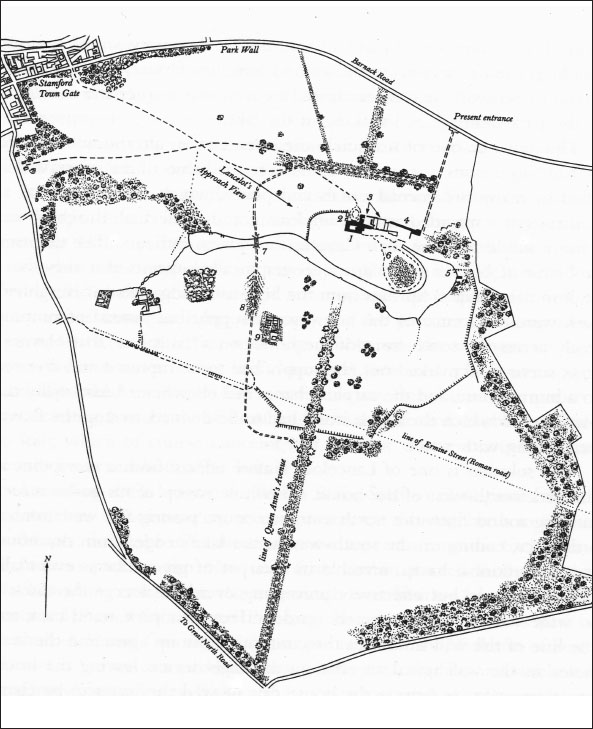

Redrawn from Capability Brown’s plan for Burghley House

© The Omnipotent Magician, Jane Brown, Chatto & Windus

‘Maps are drawn by men and not turned out automatically by machines,’ wrote the geographer J.K. Wright in his classic essay ‘Map Makers are Human’ in 1942. Times have changed: these days, maps are turned out automatically by machines, or at least by humans using machines known as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), the computer hardware and software that’s used to capture, store and display geographical and topographical data and which, according to one standard introduction to GIS, ‘is changing the world and almost everything in it’. Computer mapping systems were first developed by the Canadian government and then at Harvard University during the 1960s, and by now we’re all accustomed to maps that we can simply download, pinch, zoom and click rather than scribble on, fold and leave to rot at the bottom of a rucksack: atlases at our fingertips, giant globes in our pockets. Logically, the paper map should already be consigned to the glove compartment of history. But it isn’t.

This may be due to the fact that people simply like the look and feel of paper maps – with some people of course liking the look and feel of them much more than others. In 2006, a man called Edward Forbes Smiley III was jailed for stealing more than a hundred maps, worth $3 million, from collections at Yale, Harvard and the British Library. Smiley sliced the maps out of books using a razor blade, in much the same fashion as another famous map thief, Gilbert Bland, an antiques dealer from Florida, apparently as unassuming as his name, who was in fact, according to his biographer, the ‘Al Capone of cartography’ – though without the violence, bootlegging, bribery and late-stage neurosyphilis. Bland, like Smiley, was really just a petty thief with a taste for antique paper.

So why do people steal maps? For the same reason they steal money and books, of course: because they’re paper marked with symbols that make them valuable. But perhaps more especially, people steal maps because a map is a symbol of conquest, so the theft of a map somehow represents the ultimate conquest: the possession of the means of possession, as it were. At least, that’s my theory. No gangster mapper, I have to admit that the temptation to snaffle old paper maps has occasionally been all but overwhelming: the seventeenth-century, gold-enriched, handcoloured, multi-tinted maps issued by Willem Janszoon Blaeu and sons, for example, on display in the Dutch Maritime Museum in Amsterdam, are so extraordinary and so exquisite that only the most dimly pixel-fixated could fail to feel the stirrings of desire (Blaeu had to design and build his own printing presses in order to produce work of such quality). Or the maps produced by Christopher Saxton under the authority of Queen Elizabeth in the sixteenth century, the first ever maps of the English counties, beautiful, simple, restrained, lovingly hand-crafted by engravers and artists imported from the map-pioneering Low Countries, and popularly reproduced on playing cards. Or John Seller’s seventeenth-century sea charts: full-fathom masterpieces. Or the maps of the great Sanson family of France – no relation – whose work, in the words of one authority, was ‘always dignified and attractive, with an ornamental cartouche’. If only.