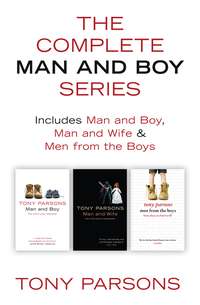

The Complete Man and Boy Trilogy: Man and Boy, Man and Wife, Men From the Boys

The police eventually came, pulling up in a blaze of sirens and twirling blue lights. Pat ran outside to meet them, his eyes wide with wonder.

There were two of them – a fit-looking young cop around my age who regarded my dad’s heroics with a quiet exasperation, and an older, heavier officer who immediately struck up a relationship with my old man.

In truth my father had never been much of a fan of the police – I remember him being stopped for speeding a few times when I was a child, and he was invariably lippy, never deferential, never willing to kiss their arses for a quiet life. Whenever he saw a police car screaming through the streets he was always contemptuous. ‘They’re only going home for their dinner,’ he would say. But now he sipped hot sweet tea with the older cop, a pair of Sunday Express readers together, two stolid real men wondering what the world was coming to as they surveyed the secured yobs at their feet.

‘You can imagine what kind of homes they come from, of course,’ said my dad.

‘The mother’s on benefits,’ guessed the old policeman. ‘The father probably buggered off years ago. If he was ever there. So the state has to pay to bring up these little charmers. Which means you and me.’

‘Too true. And don’t think they’re grateful for being supported by the taxpayer. It’s all rights these days, isn’t it? All rights and no responsibilities.’

‘You see them all over these estates. Women with a bunch of screaming kids and no ring on their fingers.’

‘Amazing, isn’t it? You need a licence to drive a car. You need a licence to own a dog. But anyone can bring a child into the world.’

I went out into the kitchen with my mum and Pat, wondering why all the decent citizens in the world have it in for single mothers. After all, I thought, the single mother is the parent who stayed.

Despite being able to eat a couple of burglars for breakfast, my father wasn’t a violent man. He wasn’t the battle-hardened war veteran of myth and movies. He was the most gentle man I ever met in my life.

It was true that I had seen him explode a few times when I was growing up. There was a sweet shop where my mother worked part-time when I was around Pat’s age, and the creep of a manager wouldn’t let her take a personal call from the hospital when her father, my granddad, was dying of cancer. I watched my dad grab the manager by the throat – the scruff of his neck, he would have called it – and lift him right off the ground. The man thought my father was going to kill him. So did I.

And there were other occasions – a cocky swimming-pool attendant who said the wrong thing when I was wearing a particularly lurid pair of water wings, a motorist who cut him up on our way to the seaside one steaming Bank Holiday Monday. He had dealt with them all the way he dealt with the two pockmarked burglars. But he never lifted a finger to me or my mother.

The war was always there, as undeniable as the jagged little black lumps of shrapnel which spent a lifetime worming their way out of his hard old body. But the real drama of his life – the friends who died before they were old enough to vote, the men he killed, the unimaginable things he saw and did – was over by the time he was out of his teens. Although I always thought of him as a warrior, a Royal Naval Commando with a silver medal on his chest, my dad had been something else for fifty years.

After the war he worked on a stall selling fruit and vegetables for five years. Then he married my mother and managed a greengrocer’s shop directly below the flat where my parents lived, childless for more than a decade, desperately trying for a baby that just wouldn’t be born.

I finally came along, when it must have seemed as though I never would, and from the day we moved out of our little flat above the shop until the day he retired, my father was a produce manager for a chain of supermarkets, travelling to stores across Kent and Essex and East Anglia to make sure the fruit and vegetables on sale were up to his demanding standards.

So he wasn’t a warrior to the world. But he was to me. And he wouldn’t hurt a fly. Quite literally wouldn’t hurt a fly. Perhaps it was because he had seen enough blood and gore to last forever, but if anything flew or crawled or crept from his well-tended garden into our small suburban home, my father would forbid my mother and me from touching it.

He would crouch beside some broken butterfly or wandering ant – or wasp or fly or mouse, no creature was too lowly or too filthy for him to rescue – scoop it up in his hands or a matchbox or a jam jar, and escort it to the back door, gently releasing it back into the wild while my mum and I mocked him and sang the chorus of ‘Born Free’.

But although we laughed at him, my childish heart reeled with admiration.

My father was a strong man who had learned to be gentle, a man who had seen enough of death to fully appreciate life. And I couldn’t compete, I just couldn’t compete.

Pat wouldn’t eat his dinner. Maybe it was the call from his mother. Maybe it was the attempted burglary. But I don’t think so. I think it was just my lousy cooking.

I had started to worry about his diet. Just how much nutrition was there in the takeaway pizzas and microwave meals I fed him on? Not much. The only time he was getting anything that remotely resembled healthy food was when we went to my parents or ate out. So one night I tried boiling up a few vegetables and slipping them into his microwaved pasta.

‘Yuk,’ he said, examining an orange blob on the end of his spoon. ‘What’s that?’

‘That’s called a carrot, Pat. You must remember carrots. They’re good for you. Come on. Eat it all up.’

He pushed his plate away with a look of disgust.

‘Not hungry,’ he said, making to get down from the kitchen table.

‘Hold it,’ I said. ‘You’re not going anywhere until you’ve eaten your dinner.’

‘I don’t want any dinner.’ He looked at the orange blob swimming in bubbling gruel. ‘This tastes yuk.’

‘Eat your dinner.’

‘No.’

‘Please eat your dinner.’

‘No.’

‘Are you going to eat your dinner or not?’

‘No.’

‘Then go to bed.’

‘But it’s early!’

‘That’s right – it’s dinner time. And if you don’t want any dinner then you can go to bed.’

‘That’s not fair!’

‘Life’s not fair! Go to bed!’

‘I hate you, Daddy!’

‘You don’t hate me! You hate my cooking! Go and put your pyjamas on!’

When he had flounced out of the kitchen I snatched up his plate of microwaved crap with added overboiled vegetables and tossed it all in the bin. Then I held the plate under the hot tap until the water burned my hands. I didn’t really blame him for not eating it. It probably wasn’t edible.

When I went into Pat’s bedroom he was lying on his bed, fully clothed, quietly sobbing. I sat him up, dried his eyes and helped him into his pyjamas. He was fading fast – eyes half-closed, mouth all puffy, head nodding like a little dashboard dog – so an early night wouldn’t do him any harm. But I didn’t want him to fall asleep hating my guts.

‘I know I’m not a very good cook, Pat. Not like Granny or Mummy. But I’m going to try harder, okay?’

‘Daddies can’t cook.’

‘That’s not true at all.’

‘You can’t cook.’

‘Well, that’s true. This daddy can’t cook. But there are lots of men who are great cooks – famous chefs in fancy restaurants. And ordinary men, too. Men who live alone. Daddies with little boys and girls. I’m going to try to be like them, okay? I’m going to try to cook you good things that you enjoy. Okay, darling?’

He turned his head away, sniffing with disbelief at something so outrageously unlikely. I knew how he felt. I couldn’t believe it either. I suspected we were both going to have to develop a profound love for sandwiches.

I took him to the bathroom to brush his teeth, and when we came back I managed to get a reluctant goodnight kiss out of him. But he wasn’t really interested in making up. Telling myself that he would have forgotten all about my rotten carrots by the morning, I tucked him in and turned out his light.

I went back to the living room and flopped on the sofa, knowing that I needed to get back to work. A bank statement had arrived that morning. I didn’t have the heart to open it.

They had sacked me the modern way – by letting my contract run out and bunging me just one month’s salary. It was already gone. So I needed to get back to work because we were desperate for money. But I also needed to get back to work because it was the only thing in this world that I was any good at.

I picked up a trade paper and turned to the situations vacant, circling production jobs in radio and TV which looked promising. But after a few minutes of half-hearted job hunting I laid the paper to one side, rubbing my eyes. I was too tired to think about it right now.

The Empire Strikes Back was still running on the video – a battle between the forces of good and evil in the snow of some faraway planet. Even though this stuff was a constant background noise in our lives and sometimes made me feel like I was losing my mind, I was just too exhausted to turn it off.

The action switched from the frozen wasteland to some dark, bubbling swamp where the wise old master was lecturing Luke Skywalker on his destiny. And I suddenly realised how many father figures Luke has, father figures who seem to cover the waterfront of parental possibilities.

There’s Yoda, the wrinkled elder who has good advice coming out of his pointy green ears. And then there’s Obi-Wan Kenobi, who combines homespun homilies with some old-fashioned tough love.

And finally there’s Darth Vader, the Dark Lord of the Sith, who is probably more in keeping with the spirit of our time – an absent father, a neglectful dad, a selfish old man who puts his own wishes – in Mr Vader’s case, a desire to conquer the universe – before any parental responsibility.

My old man was definitely the Obi-Wan Kenobi type. And that’s the kind of father I wanted to be too.

But I fell asleep on the sofa surrounded by the situations vacant, suspecting that I would always be a lot more like the man in the black hat, a father with not enough patience, not enough time, forever lost to the dark side.

Fourteen

‘I know there’ve been a few problems at home,’ the nursery teacher said, making it sound as though the dishwasher was playing up, making it sound as though I could just pick up Yellow Pages and sort out my life. ‘And believe me,’ she said, ‘everyone at Canonbury Cubs is sympathetic.’

It was true. The teachers at Canonbury Cubs always made a big fuss of Pat when I delivered him in the morning. As the blood drained from his face yet again, as his bottom lip started to quiver and those huge blue eyes filled up at the prospect of being taken away from me for another day, they really couldn’t have been kinder.

But ultimately he wasn’t their problem. And no matter how kind they were, they couldn’t mend the cracks that were showing in his life.

Unless it was to be with my fun-mad parents, Pat didn’t like being separated from me. There was high drama when we parted at the gate of Canonbury Cubs every morning and then I went home to pace the floor for hours, fretting about how he was doing, while back at the nursery poor old Pat kept asking the teachers how long before he could go home and crying all over his finger paintings.

Nursery wasn’t working. So amid their concerned talk about possibly finding a child psychologist and time healing all wounds, Pat dropped out.

As the other kids started work on their Plasticine worms, I took Pat’s hand and led him out of that rainbow-coloured basement for the last time. He cheered up immediately, far too happy and relieved to feel like any kind of misfit. The teachers brightly waved goodbye. The little children looked up briefly and then returned to their innocent chores.

And I imagined my son, the nursery-school dropout, returning to the gates of Canonbury Cubs in ten years’ time, just to sneer and leer and sell them all crack.

The job seemed perfect.

The station wanted to build a show around this young Irish comedian who was getting too big to do the clubs yet who was not quite big enough to do beer commercials.

He didn’t actually do anything as old-fashioned as tell jokes, but he had wowed them up at the Edinburgh Festival with an act built completely around his relationship with the audience.

Instead of telling gags, he spoke to the crowd, relying on intelligent heckling and his Celtic charm to pull him through. He seemed born to host a talk show. Unlike Marty and every other host, he wouldn’t be dependent on celebrities revealing their secrets or members of the public disgracing themselves. He could even write his own scripts. At least that was the theory. They just needed an experienced producer.

‘We’re very excited to see you here,’ said the woman sitting opposite me. She was the station’s commissioning editor, a small woman in her middle thirties with the power to change your life. The two men in glasses on either side of her – the show’s series producer and the series editor – smiled in agreement. I smiled back at them. I was excited too.

This show was just what I needed to turn my world around. The money was better than anything I had ever got working for Marty Mann, because now I was coming from another television show instead of some flyblown outpost of radio. But although it would be a relief not to worry about meeting the mortgage and the payments on my car, this wasn’t about the money.

I had realised how much I missed going to an office every day. I missed the phones, the meetings, the comforting rituals of the working week. I missed having a desk. I even missed the woman who came around with sandwiches and coffee. I was tired of staying at home cooking meals for my son that he couldn’t eat. I was sick of feeling as if life was happening somewhere else. I wanted to go back to work.

‘Your record with Marty Mann speaks for itself,’ the commissioning editor said. ‘Not many radio shows can be made to work on television.’

‘Well, Marty’s a brilliant broadcaster,’ I said. The ungrateful little shitbag. May he rot in hell. ‘He made it easy for me.’

‘You’re very kind to him,’ the series editor said.

‘Marty’s a great guy,’ I said. The treacherous, treacherous little bastard. ‘I love him.’ My new show’s going to blow you out of the water, Marty. Forget the diet. Forget the personal trainer. You’re going back to local radio, pal.

‘We hope that you can have the same relationship with the presenter of this show,’ the woman said. ‘Eamon’s a talented young man, but he is not going to get through a nine-week run without someone of your experience behind him. That’s why we would like to offer you the job.’

I could see the blissful, crowded weeks stretching out ahead of me. I could imagine the script meetings at the start of the week, the minor triumphs and disasters as guests dropped out and came in, the shooting script coming together, the nerves and cock-ups of studio rehearsal, the lights, cameras and adrenaline of doing the show, and finally the indescribable relief that it was all over for seven more days. And, always, the perfect excuse to avoid doing anything I didn’t want to do – I’m too busy at work, I’m too busy at work, I’m too busy at work.

We all stood up and shook hands, and they came with me out into the main office where Pat was waiting. He was sitting on a desk being fussed over by a couple of researchers who stroked his hair, touched his cheek and gazed with wonder into his eyes, shocked and charmed by the sheer dazzling newness of him. You didn’t get many four-year-olds in an office like this.

I had been a bit worried about bringing Pat with me. Apart from the possibility of him refusing to be left outside the interview room, I didn’t want to rub their noses in the fact that I was currently playing the single parent. How could they hire a man who had to lug his family around with him? How could they give a producer’s job to a man who couldn’t even organise a babysitter?

I needn’t have worried. They seemed surprised but touched that I had brought my boy to a job interview. And Pat was at his most charming and talkative, happily filling the researchers in on all the gory details of his parents’ separation.

‘Yes, my mummy is in abroad – in Japan – where they drive on the left side of the road like us. She’s going to get me, yes. And I live with my daddy, but at weekends I sometimes stay with my nan and granddad. My mummy still loves me, but now she only likes my dad.’

His face lit up when he saw me, and he jumped down off the desk, running to my arms and kissing me on the cheek with that fierceness he had learned from Gina.

As I held him and all those television people grinned at us and each other, I glimpsed the reality of my new brilliant career – the weekends spent writing a script, the meetings that started early and finished late, the hours and hours in a studio chilled to near freezing point to stop beads of sweat forming on the presenter’s forehead – and I knew that I would not be taking this job.

They liked the single father and son routine when it had a strictly limited run. But they wouldn’t like it when they saw me buggering off at six every night to make Pat’s fishfingers.

They wouldn’t like it at all.

Fifteen

I called Gina when Pat was staying overnight with my mum and dad. I had realised that I needed to talk to her. Really talk to her. Not just shout and whine and threaten. Tell her what was on my mind. Let her know what I was thinking.

‘Come home,’ I said. ‘I love you.’

‘How can you love someone – really love them – and sleep with someone else?’

‘I don’t know how to explain it. But it was easy.’

‘Well, forgiving is not quite so easy, okay?’

‘Christ, you really want to see me crawl, don’t you?’

‘It’s not about you, Harry. It’s about me.’

‘What about our life together? We have a life together, don’t we? How can you throw all that away because of one mistake?’

‘I didn’t throw it away. You did.’

‘Don’t you love me any more?’

‘Of course I love you, you stupid bastard. But I’m not in love with you.’

‘Wait a minute. You love me, but you’re not in love with me?’

‘You hurt me too much. And you’ll do it again. And next time you won’t feel quite so much guilt. Next time you’ll be able to justify it to yourself. Then one day you’ll meet someone you really like. Someone you love. And that’s when you’ll leave me.’

‘Never.’

‘That’s the way it works, Harry. I saw it all with my parents.’

‘You love me, but you’re not in love with me? What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Love is what’s left when being in love has gone, okay? It’s when you care about someone and you hope they’re happy, but you’re not under any illusions about them. Maybe that kind of love is not exciting and passionate and all those things that fade with time. All those things that you’re so keen on. But in the end it’s the only kind of love that really matters.’

‘I have absolutely no idea what you’re going on about,’ I said.

‘And that’s exactly your problem,’ she told me.

‘Forget Japan. Come home. You’re still my wife, Gina.’

‘I’m seeing someone,’ she said, and I felt like a hypochondriac who has finally had his terminal disease confirmed.

I wasn’t surprised. I had spent so long being terrified that finally having my worst fears realised brought a kind of bleak relief.

I had been expecting it – dreading it – ever since she had walked out the door. In a way I was glad it had happened, because now I didn’t have to worry about when it was going to happen. And I wasn’t so stupid that I thought I had the right to be outraged. But I still hadn’t worked out what to do with our wedding photographs. What are you meant to do with the wedding photographs after you split up?

‘Funny old expression, isn’t it?’ I said. ‘Seeing someone, I mean. It sounds like you’re checking them out. Observing them. Just looking. But that’s exactly what you’re not doing. Just looking, I mean. When you’re seeing someone, well, it’s gone way beyond the just looking stage. How serious is it?’

‘I don’t know. How do you tell? He’s married.’

‘Fuck me.’

‘But it’s not – apparently it hasn’t been good for ages. They’re semi-separated.’

‘Is that what he told you? Semi-separated? And you believed him, did you? Semi-separated. That’s a suitably vague way of putting it. I haven’t heard that one before. Semi-separated. That’s very good. That just about covers any eventuality. That should allow him to string both of you along nicely. He can keep the little wife at home making sushi while he sneaks off with you to the nearest love hotel.’

‘Oh, Harry. The least you could do is wish me well.’

‘Who is he? Some Japanese salary man who gets his kicks by sleeping with western women? You can’t trust the Japanese, Gina. You think you’re the big expert, but you don’t know them at all. They don’t have the same value system as you and me. The Japanese are a cunning, double-dealing race.’

‘He’s American.’

‘Well, why didn’t you say? That’s even worse.’

‘You wouldn’t like anyone I got involved with, would you, Harry? He could be an Eskimo and you would say – “Ooh, Eskimos, Gina. Cold hands, cold heart. Steer well clear of Eskimos, Gina.”’

‘I just don’t understand why you’ve got this thing about foreigners.’

‘Perhaps because I tried loving someone from my own country. And he broke my heart.’

It took me a moment to realise that she was talking about me.

‘Does he know you’ve got a kid?’

‘Of course he knows. Do you think I would hide that from anyone?’

‘And how does he feel about it?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Is he interested in Pat? Is he worried about the boy? Does he care about his wellbeing? Or does he just want to fuck his mother?’

‘If you’re going to talk like that, Harry, I’m going to hang up.’

‘How else am I meant to put it?’

‘We haven’t talked about the future. We haven’t got that far.’

‘Let me know when you get that far.’

‘I will. But please don’t use Pat as a rod for my back.’

Is that what I was doing? I couldn’t tell where my genuine concern ended and my genuine jealousy began.

Pat was one of the reasons I wanted to see Gina’s boyfriend dead in a car crash. But I knew he wasn’t the only reason. Maybe he wasn’t even the main reason.

‘Just don’t try to poison my son against me,’ I said.

‘What are you talking about, Harry?’

‘Pat tells everyone he meets that you said you love him but you only like me.’

She sighed.

‘That’s not what I said. I told him exactly what I’ve just told you. I told him that I still loved you both but unfortunately and sadly I was no longer in love with you.’

‘I still don’t know what that means.’

‘It means that I’m glad for the years we spent together. But you hurt me so much that I can never forgive you or trust you again. And I think it means that you’re no longer the man I want to spend the rest of my life with. You’re too much like any other man. Too much like my father.’

‘It’s not my fault that your old man walked out on you and your mum.’

‘You were my chance to get over all that. And you messed it up. You left me, too.’

‘Come on. It was one night, Gina. How many times are we going to have this conversation?’

‘Until you understand the way I feel. If you can do it once, you can do it a thousand times. That’s the first law of fucking around. The unified theory of fucking around clearly states that if they do it once, they will do it again and again. You broke my trust and I just don’t know how to mend it. And that hurts me too, Harry. I wasn’t trying to turn Pat against you. I was just trying to explain the situation to him. How do you explain it?’