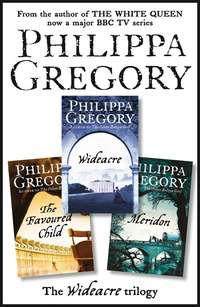

The Complete Wideacre Trilogy: Wideacre, The Favoured Child, Meridon

‘I hope you did not mind,’ he asked tentatively. He looked up at me and took one still, unresponsive hand. I looked as if I had no idea why I should mind. My hazel eyes fixed on the fire were wide open with detached and polite interest in Harry’s conversation.

‘I was afraid of us as lovers,’ he confessed honestly, his eyes fixed on my face. Still I said nothing. My confidence was growing but I was still chilled inside from my sad vigil in the wood. And I would never love a man who did not love me more.

He fell silent and I let the silence stretch.

‘Beatrice,’ he said again. ‘I will do anything …’

It was a clear plea. I had won.

‘I must go to bed,’ I said, standing. ‘I promised Mama I would not stay up late. We did not expect you back so soon.’

‘Beatrice,’ he said again, looking up at me.

If I had slackened my control and allowed so much as one of my fingers to touch one of the curls of his head, I should have been lost. I would have collapsed to the hearth rug with him and he would have taken me that night and left me the following morning for Celia on a pendulum that would have swung every day of a miserable life. I had to win this struggle with Harry. If once I lost him, I lost not only the love of the one man I wanted, but I also lost Wideacre. I had staked my life’s happiness on this indecisive, conscience-ridden creature and I had to win. Against his own good conscience and against his own good, sweet betrothed, I had set his passionate nature and the taste of perverse pleasure he had with me – my whip on his thigh, the taste of blood when I bit his lips, which he would never have with gentle Celia.

I smiled down at him but took care not to touch him.

‘Goodnight, Harry,’ I said. ‘Perhaps we will ride on the downs together tomorrow.’

I undressed slowly in a dream by candle-light, hardly knowing whether my desperate gamble had won me security or whether I had lost everything. Was Harry even now on his knees at his bedside praying like a good child for God to keep him pure? Or was he still kneeling by my chair in the parlour burning with desire? I slid between the sheets and blew out the candle. In the dark I could hear the house settle in the silence but I lay wakeful, reliving the scene downstairs and aching for my lover. I waited for sleep but I expected to lie awake. My aroused heart beat fast and every muscle in my body quivered in expectation.

In the silence of the night I heard an odd, soft noise and I held my breath to listen. I heard it a second time – the creak of a board in the passage outside my door and then – the most welcome sound in the whole world – a soft sad moan as Harry pressed his forehead to the unyielding wood of my door and kneeled on the floorboards outside my room.

He did not dare to try the handle of the door; he did not dare even to tap on the door to see if I would let him in. He was like a whipped dog in the passageway and knew his master at last. He knelt in longing and in remorse and silence on my threshold. And I let him wait there.

I turned over in bed, smiled in silent delight … and slept like a baby.

My mother teased Harry about the dark shadows under his eyes at breakfast and said she did not know what to blame – Celia’s pretty face or Lord Havering’s port. Harry smiled with an effort and said with careful nonchalance, ‘A morning’s gallop on the downs will soon blow the cobwebs away, Mama! Will you come riding with me today, Beatrice?’

I smiled and said, ‘Yes,’ and his face lightened. I said not another word at breakfast, nor did I speak until we had ridden up past our fields where the corn was ripening to the downs. Harry led the way like a practised lover to our little hollow among the ferns, dismounted and turned to help me.

I kept my seat and looked steadily down until I saw his confidence waver.

‘You promised me a gallop,’ I said lightly.

‘I have been a fool,’ he said. ‘I have been mad, Beatrice, and you must forgive me. Forget yesterday, remember only the day before. Don’t give me that pleasure and then rob me of it. Punish me another way, be as cruel to me as you like but don’t teach me of the loveliness of your body and then take it from me. Don’t condemn me to live in the house with you, to see you every day and yet never be able to hold you again! Don’t condemn me to a living death, Beatrice!’

He stumbled to a halt on what was nearly a sob and as he raised his face I saw his mouth trembling. I reached out to him and let him hold me as I slid down from the saddle. But I freed myself when my feet touched the turf and stepped back so we did not touch. His eyes were hazy blue with desire and I knew mine were dark. The slow, warm heat of arousal was beating in my body and my control over myself and over this scene was slipping fast. My anger at Harry and my conflicting desire to be under him again fused into one passion of love and hatred. With my full force I slapped him as hard as I could on the right cheek and then struck him a violent back-handed blow on his left cheek.

Instinctively, he jerked back and lost his footing over a tussock of grass. I followed, and still guided by wordless anger, kicked him as hard as I could in the ribs. With a great groan of pleasure he doubled up on the grass and kissed the toe of my riding boot. I tore off my dress as he ripped his breeches away and flung myself like a wildcat on him. Both of us screamed as I rode him astride, like a stable lad breaking a stallion. I pounded his chest, his neck and his face with my gloved fists until the climax of pleasure felled me like a pine tree to lie beside him. We lay as still as corpses under our sky for hours. I had won.

The following day I went to call on Celia. Mama chose to come too and she and Lady Havering closeted themselves in the parlour with wedding-dress patterns and tea and cakes while Celia and I were free to wander in the garden.

Havering Hall is a bigger house than Wideacre – built on a different scale as a great showpiece, while Wideacre has always been a manor house extended and improved, but firstly a beloved home. Havering is large, rebuilt in the last century in the baroque style, which was popular then, with plenty of stone garlands and statuary niches and swags of stone ribbons over the windows. If you like that sort of thing it is said to be a fine example. I think it fussy and overdone. I prefer the plain clean lines of my home with the windows set honest and straight in the sand-coloured walls and no fancy pillars blocking the sunlight from the front rooms.

The gardens were laid out at the same time and they show the neglect even worse than the house. The paths were planned with a ruler and compass to follow straight lines around square and rectangular flower beds leading one, like a bored pawn on a gravel and grass chessboard, to the square ornamental pond in the centre of the garden where the carp are supposed to fin among flowering water lilies, and the fountains play.

In practice, the pond is dried out because it sprang a leak and no one had the wit to find the hole and have it mended. The fountains never played well because of low water pressure, and when the pump broke they stopped for ever. The carp benefited the herons but no one else.

The ornamental flower beds may still preserve their soldier-straight rows of flowering plants and the centre crowns of roses, but it is hard to tell for the towering weeds. They are the friendly wild flowers of my Wideacre childhood – rosebay willowherb, gypsy’s lace, wild foxgloves. But they look like a sign of the end of the world in these formal gardens. The ladies of Havering – Celia’s mama, herself and her four stepsisters – can see no solution but to wander around the garden saying, ‘Dear, dear’ at the greenfly and the suckers and the crumbling flower-bed edges. A week’s hard work by two sensible men would reverse the decay, and anyone but a fool would set them to it. But the ladies of Havering prefer to endure, with sad acceptance, the rack and ruin of garden and, more seriously, of farmland.

‘It is a shame,’ Celia concurred. ‘But the house is worse. It is so gloomy with the furniture under dust sheets and bowls out to catch the drips of water when it rains. And in winter it is really very cold.’

I nodded. I could sympathize with Celia’s position as a stepdaughter from a previous marriage brought into a home both overpoweringly grand and unnecessarily uncomfortable. But for Celia our lands and our position were not just enviable for themselves – they were her refuge from the discomforts and humiliations of her home. With good management, a lot could have been done with the Havering estate; Harry and I expected a handsome profit from Celia’s dowry lands. After all, we shared the same good soil and easy weather. There was no God-given reason that Wideacre cattle should be twice the size of the Havering beasts, or that Wideacre fields should offer double the yield. Except, of course, for the crucial ingredient of the Master’s boot. Wideacre had never been neglected by an absentee landlord spending the profits faster than they grew.

Wideacre Hall might be plain and unfashionable. The rose garden might be modest and too like simple gardens of cottages and small farmhouses. But that was because when the land yielded a good golden profit, the money went back into the land, repairing buildings, fences and gates; buying time so fields could be rested between sowings; carting mulch from the stables to make the earth yield in greater and greater abundance. But Lord Havering cared nothing for the land except as a source of gambling money, and his wife and his daughters could live in a broken-down barn for all he cared as long as he had an income from his rack-rents to gamble away at White’s or Brooks’s in London.

‘You will be glad to get to Wideacre,’ I said sympathetically.

‘I will,’ she said. ‘Especially with you there, dearest Beatrice. And your mama too, of course.’

‘I am surprised, then, that you are going on a wedding tour,’ I said carefully. ‘Was it your idea?’

‘It was,’ she said dolefully. ‘It was. Oh, Beatrice!’ She glanced guiltily back at the house as if her mama’s stern face was looking out of the windows, or as if her four stepsisters might at any moment creep out and eavesdrop. Abruptly she guided us into an overgrown arbour and sat down. I sat down beside her and put a sisterly arm around her.

‘It was my idea when Harry was so sweet and gentle,’ she said. ‘I thought we would go to Paris and Rome and hear the lovely concerts, and make visits and things …’ Her voice tailed off. ‘But now when I think of marriage and the things one has to do, I wish I had never suggested it! Just think of being quite alone for weeks!’ My body melted at the very thought of being alone with Harry for weeks, but I kept a proper face of sisterly concern.

‘If only your mama could come with us,’ Celia said wildly. ‘Or Beatrice … or … or … or you!’

I was genuinely surprised.

‘Me?’ I said. I had thought only of stopping the tour but this was a new development.

‘Yes,’ she said quickly. ‘You can come and keep me company while Harry is visiting his farms and lectures, and then when I am sketching you can keep Harry company in Rome.’

The idea of keeping Harry company in Rome made my head spin with imagined pleasure.

‘Oh, Beatrice, say you will!’ she said quickly. ‘It is quite customary. Last year Lady Alverstoke took her sister on her wedding tour, and Sarah Vere did so too. Beatrice, do come with us as a favour to me. Your company would make all the difference in the world to me, and I’m sure Harry would like it too. We could all have such fun.’

‘We could,’ I said slowly. In my mind’s eye were hot, sunlit afternoons with Celia sketching with her maid, or making calls, while Harry and I lay luxuriously together in the sunlight. Or in the evening while Celia attended a concert, Harry and I in a little discreet house dining together, and then retiring to a private room with a bottle of champagne. Of the long, sensuous hours while Celia was fitted with Paris clothes, of the snatched moments while Celia wrote letters to her mama. Of daily rides together in foreign scenes, of little secret places we would find to hide and embrace.

‘Promise you will come!’ Celia said desperately. ‘It is yet another favour I ask of you, I know. But promise me you will!’

I took her fingers that trembled so pitifully in a comforting sisterly grasp.

‘I promise I will come,’ I said reassuringly. ‘As a special favour to you, dear Celia, I will come.’

She held my hand as a drowning man might clutch at a branch. And I let her cling to me. Celia’s hero worship of me might be tedious, but it gave me a strong hold on her and on Harry through her. We were sitting, hand-clasped, when her stepbrother George came running out to find us.

‘Good afternoon, Miss Lacey,’ he said, blushing the rosy red of a coltish fourteen-year-old boy. ‘Mama sent me to find you to tell you that your mama is ready to leave.’

Celia fluttered ahead of us up the weed-strewn path to the house while George offered me his arm with elaborate courtesy.

‘They have been talking about the bread riots,’ he said with an awkward attempt at conversation with the lovely Miss Beatrice, the toast of the county.

‘Oh, yes,’ I said with polite interest. ‘Bread riots where?’

‘In Portsmouth, Mama said, I think,’ he said vaguely. ‘Apparently a mob broke into two bakers’ claiming the bread was made with adulterated flour. They were led by a legless gypsy on horseback. Fancy that!’

‘Fancy,’ I repeated slowly, uneasy with a feeling of dread I could not properly understand.

‘Fancy a mob being led by a man on a horse,’ George said with youthful scorn. ‘Why, next they’ll be looting with a curricle and pair.’

‘When was this?’ I asked sharply, some premonition drawing a cold fingernail down my spine.

‘I don’t know,’ said George. ‘Some weeks ago, I think. They’ve probably all been caught by now. I say, Miss Lacey, will you dance at Celia’s wedding?’

I found a smile to meet his open admiration. ‘No, George,’ I said kindly. ‘I shan’t be fully out of mourning. But when I am, at the first party I shall dance with you.’

He coloured up to his ears and escorted me up the steps to the Hall in breathless silence. Mama and Lady Havering were not speaking of the Portsmouth bread riots when we entered the drawing room, and there was no opportunity to ask more about it. It remained a faint shadow on my mind, like the cold shiver that country people say is someone walking over your grave. I did not like to hear of angry men on horses, of legless men leading mobs. But I could hardly have said why.

In any case, the most pressing problem before me was to seize my God-given chance to join the wedding tour. Some wise instinct made me delay telling Harry that his bride had asked me along for company until we were at tea: Mama, Harry and myself. I wanted to make sure that Harry could not refuse me as a lover what he could be forced to grant me as a brother.

I stressed that it was Celia’s invitation to me, and said that I had told her I could give her no answer without mama’s consent. I watched Harry’s face carefully and saw the brief leap of anticipation and pleasure at the news, succeeded by the more permanent expression of doubt. Harry’s good conscience had the upper hand again and I realized, with a pang of jealousy and pain, that he was looking forward to being alone with Celia, far away from her overbearing mother, far away from his stultifying, smothering, loving mama. Far away, even, from his desirable, mysterious sister.

‘It would be a marvellous opportunity for you,’ Mama said, glancing towards Harry to guess what her darling boy would prefer. ‘And so like Celia to think of giving you pleasure. But perhaps Harry feels he needs you here while he is away? There is always a lot of work to do on the land in autumn, I know your papa used to say so.’

She turned to Harry, having prepared the ground so he could merely indicate his wishes and we would all rush to satisfy them. Everything in this house went to Harry. I curbed my impatience.

‘Celia was actually begging me to come,’ I said, a smile on my face. I looked directly at Harry down the walnut table. ‘She rather dreads, I think, being left in a strange town while Harry seeks out some experimental farmer.’ My eyes held his and I knew he would read my secret message. ‘She does not yet share your tastes, as I do.’

He knew what I meant. Mama glanced curiously from his face to mine.

‘Celia has many years ahead of her to learn to share Harry’s tastes,’ she said gently. ‘I am sure she will do her very best to please him and make him happy.’

‘Oh, yes,’ I said in ready agreement. ‘I am sure she will make us all happy. She is such a sweet good girl; she will be a marvellous wife.’

The thought of a lifetime with a ‘marvellous wife’ cast a shadow over Harry’s face. I took a gamble on Mama’s innocence and rose from my seat and walked to the head of the table. To Mama’s view from the foot I was prettily coaxing my dear brother, but he and I knew as I came near him the speed of his pulse was raised and, at my touch and at the smell of my warm perfumed skin, his breathing became faster. I kept my back to Mama and put my cheek against his face. I felt his skin grow hot under mine and I knew that my touch, the glimpse of my breasts at the top of my gown, were winning the battle for me against Harry’s weathercock feelings. There was never any need to argue with Harry. He was lost at the first reminder of pleasure.

‘Do take me with you, Harry,’ I pleaded, in a low coaxing tone. ‘I promise I will be good.’ Hidden from our mother, I breathed a kiss high on his cheek near his ear. He could stand no more and gently pushed me from him. I saw the muscles around his eyes were tense with self-control.

‘Of course, Beatrice,’ he said courteously. ‘If that is what Celia desires, I can think of no more agreeable arrangement. I shall write her a note and join you and Mama in the parlour for tea.’

He got himself quickly out of the room to cool off and left me alone with Mama. She was peeling a peach and did not look at me. I slipped back into my seat and cut a few grapes from the fat cluster with a pair of delicate silver scissors.

‘Are you sure you should go?’ Mama asked evenly. She kept her eyes on her neat hands.

‘Why not?’ I asked idly. But my nerves were alert.

She groped for a good reason and could not answer me at once.

‘Are you anxious at being left alone?’ I asked. ‘We shall not be gone very long.’

‘I do think it would be easier if you stayed,’ she concurred. ‘But I dare say I can manage for six or eight weeks. It is not Wideacre …’ She let the sentence hang, and I did not help her to complete it.

‘Perhaps they need time to be alone together …’ she started tentatively.

‘Whatever for?’ I said coolly, gambling on her belief in my virginal innocence. Gambling also on her own experience of marriage, which had not included courtship as a preliminary, nor a honeymoon as an introduction, but had been a business arrangement contracted for profit and concluded without emotion, except mutual dislike.

‘Perhaps you and Harry would do well to be apart …’ she said, even more hesitantly.

‘Mama,’ I said challengingly with my brave courage high. ‘Whatever are you saying?’

Her head jerked up at the strength in my voice and her pale eyes looked half frightened.

‘Nothing,’ she said, almost whispering. ‘Nothing, child. Nothing. It is just that sometimes I am so afraid for you – for your extreme passions. First you adored your father to such a height of feeling, and then you transferred that affection to Harry. All the time you will do nothing but roam around Wideacre as if you were a ghost haunting the place. It frightens me to see you so obsessed with Wideacre, so constantly with Harry. I just want you to have a normal, ordinary girlhood.’

I hesitated. ‘My girlhood is normal and ordinary, Mama,’ I said mildly. ‘It is not like yours because times are changing. But even more so because you were reared in town whereas I have had a country childhood. But I am no different from girls of my own age.’

She remained uneasy, but she would never have the courage to look into the pictures she had of Harry and me, to see clearly what was taking place before her frightened half-shut eyes.

‘I dare say you are not …’ she said. ‘I cannot judge. We see so few young people. Your papa had little time for county society and we live so withdrawn … I can hardly judge.’

‘Don’t be distressed, Mama,’ I said soothingly, my voice warm with assumed affection. ‘I am not obsessed with Wideacre, for, see, I am leaving in mid-autumn, one of the loveliest seasons. I am not possessive of Harry for I am happy at his marriage and I am making close friends with Celia. There is nothing to fear.’

Mama had neither wits sharp enough nor instincts true enough to filter truth from lies. In any case, if the truth of my relationship with Harry had stared her in the face she would have died rather than see it. So she swallowed her last slice of peach and gave me an apologetic smile.

‘I am foolish to worry so,’ she said. ‘But I do feel the responsibility of you and Harry heavily on me. Without your papa you two have only me to guide you and I am anxious that ours shall be a truly happy home.’

‘Indeed it is,’ I said firmly. ‘And when Celia lives here with us all it will be even happier.’

Mama rose to her feet and we walked together to the door. I opened it for her in a pretty gesture of courtesy and she paused to give me a gentle kiss on the cheek.

‘God bless you, my dear, and keep you safe,’ she said tenderly, and I knew she was reproaching herself for her lack of warmth towards me, and for the unease she felt when she saw me with my arms around my brother’s neck.

‘Thank you, Mama,’ I said, and the gratitude in my voice was not assumed. I was truly moved by her attempt to do her duty by me, and to love me into the bargain. She had hurt me, and her preference for Harry turned my heart to ice towards her. But I could recognize her honest, honourable attempt to care for Harry and me equally.

‘I’ll order tea,’ she said and left the room.

She left me beside the dining table, turning over a conflict of feelings. If only life was as my mama perceived it, how simple it would be. If Harry and I had an easy, sinless working partnership, if Harry’s marriage was a real one of love, if my future could be a happy one in a new home with a loving husband – how easy it would be to live without sin. Then the door opened and Harry came in, his letter to Celia half finished in his hand.

‘Beatrice,’ he murmured. We faced each other at the foot of the polished table, our faces reflected in the dark wood. He had the face of an angel, and the shadowy reflection only made his clear-cut features more luminous. As I glanced down at the table I saw my own face, pale as a ghost with my white powdered hair piled on my head, regal as a queen. But my eyes were large and serious, and my mouth was sad. We appeared what we were: a weak boy and a proud and passionate young woman. But for that moment we could have halted the process we had, half consciously, started. I was filled with a sense of peace at my mother’s gentle blessing, at her humility and at her own confused quest for proper behaviour in a world where sin was in every corner of her house, half sensed, half understood, but secretly threatening. Watching her struggle to find the courage to confront the truth, her struggle to love me, I saw the pattern of another sort of life, one where people might choose renunciation rather than grabbing for pleasure. Where one might count the cost in moral terms, and decide it was too high. Where one might search for goodness rather than gratification.

But the vision was a brief one.