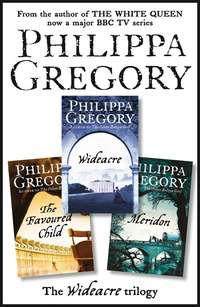

The Complete Wideacre Trilogy: Wideacre, The Favoured Child, Meridon

But they were not good enough for Harry. He calculated that if the water level were to be regulated at its source in a little steep-sided downland valley with a wall to hold back the growing river, then all the extra field space we allowed for flooding could be ploughed up and used. The empty extra curves around the riverbed, the water-meadows that flood twice a year, could all be put under his blessed plough to grow more and more of his damned wheat. So Harry listened courteously and politely to all the wise old men, and paid them no heed. My letters of excitable remonstrance he ignored, too. Too clever for his own good was Harry, and the old tenants sent their sons out to build his dam and fit its pretty little sluice gates and dig out its little channels, and they laughed behind their hands at the waste, and the cost and, I dare say, at what Miss Beatrice would have to say when she came home, and the rage she would be in.

What happened next could have been predicted by any fool except the fool who now squired Wideacre. The waters behind Harry’s, new-built dam backed up in the little valley far faster than he had anticipated. He had measured the flow of the Fenny, but not allowed for the fact that when the snow melts and we have heavy spring rains the whole land becomes wetter and there are streams where he had never guessed streams would flow. The swelling lake drowned a hazel coppice that was older than Wideacre itself, and waterlogged some good dry upland meadow fields. As the waters built up, the nice little sluice gates struggled to open and close to control the flood; the new plaster in the wall melted like springtime ice; the dam crumbled and a great wall of water, high as a house, thundered down the little valley towards Acre.

It knocked out the road bridge in the first splashy roaring collision and Harry could thank his fool’s luck that there were no small children sitting on the parapet or old men smoking and staring at the stream when that deadly wall of water ripped the sound old bridge out by its roots.

It spread then, a wide sweep of destruction as careless as a fan brushed across a table of ornaments. Crops, shrubs, bushes and even large shallow-rooted firs were bowled over in a broad swathe for twenty feet on either side of the banks. So Harry’s proud new wheat crop on the old water-meadows was ripped out of the earth before it had even rooted, and all his newly claimed fields were littered with mud and rubble and broken trees.

The flood hit the new mill with some of its force spent and, although the yard was flooded, the building had stood firm. Ground-floor windows and doors were staved in and some of the grain spoiled, but the new buildings were sound and strong. The old mill, where Ralph and I had met and loved, and Meg’s rickety hovel were swept away altogether. Only two walls of the mill were left standing and that sweet flowering green bank washed clean of our footprints. Even the straw he had picked off my skirts was gone, whirling downstream on the floodtide.

Then the worst of the flood was spent and the river returned to its banks. Harry wrote me that he had been greeted with anxious faces when he rode out the next day, but I knew there would have been smiles behind his back. Every scrounger on Wideacre would have profited from the Squire’s folly and the claims of flood damage would be sky high. Harry had to find the money and the workers to rebuild the bridge and the road; he had to compensate the tenants whose lands had been damaged and crops spoiled. He had to buy Mrs Green new glass for her windows and chintz for her curtains. When I read his doleful letter describing the damage and the claims he faced I had been hot with rage at his folly and the waste of it all. But now I was just as anxious to be home so I could set all to rights again.

Besides, there were things I could not ask Harry, but could only see for myself. How the young doctor was getting on, and whether Lady Havering had managed to catch him for one of Celia’s pretty sisters; if he remembered his passing liking for me. My heart stayed rock-steady at the thought of him – he was not a man who would excite or challenge me – and he could not gain me Wideacre – but his attention had flattered my vanity at a time when I needed a diversion, and he intrigued me. He was so unlike the men I knew – men of the land like squires, bluff farmers and county leaders. But my heart beat no faster at the thought of him. He had no mystery, no magic like Ralph. He did not hold the land and charm me like Harry. He could only interest me. But if he were still single, and still smiling with cool blue eyes at me, then I was happy to be interested.

I gazed out to sea where the waves followed each other like wandering, rolling hills and faced the principal question that awaited me at home: if the villains of the Kent attack had all been rounded up, sentenced and hanged; or whether one – just one, the leader with his two black dogs and his black horse – was still free. The question no longer woke me screaming every night, although the black horse continued to ride through my occasional nightmares. But the thought of my lovely strong Ralph swinging himself about on crutches, or worse still shuffling his body along the ground like a dog in the gutter, would always make me feel sick with fear and disgust. I took care to keep the picture from my mind, and if it came, unbidden, when I closed my eyes for sleep I took a good measure of laudanum and escaped.

If the corn rioters were all taken I could sleep in peace. He might well be dead already. He could have been executed in his disguise and no one ever thought to tell Wideacre, and certainly no one troubled enough to send the news to us in France. The figure who still haunted my darkest nightmares might be a ghost indeed, and I had no fear of dead men.

But if he were dead I felt I would mourn him. My first lover, the boy, then the man, who had spoken so longingly of the land and pleasure and the need to have them both. The clever youth who saw so young that there are those who give and those who take love. The daring, passionate, spontaneous lover who would fling himself on me and take me without doubt and without conscience. His frank sensuality had matched mine in a way that Harry never could. If he had only been of the Quality … but that was a daydream that would lead nowhere. He had killed for Wideacre; he had nearly died for it. All I had to hope was that the noose had done what the spring of the mantrap had half done, and that the love of my childhood, girlhood and womanhood was dead.

‘Is that – can that be land?’ asked Celia suddenly. She pointed ahead and I could see the faintest dark smudge like smoke on the horizon.

‘I don’t think it can be yet,’ I said, straining my eyes. ‘The captain said not till tomorrow. But we have had good winds all day.’

‘I do believe it is,’ said Celia, her pale cheeks flushed with pleasure. ‘How wonderful to see England again. I shall fetch Julia to catch her first glimpse of her home.’

And away down the hatch she went and came up with the baby, nurse and all the paraphernalia of infancy so that the baby could be pointed to the prow and face her homeland.

‘It’s to be hoped she’s more excited by the sight of her father,’ I said, watching this nonsense.

Celia laughed without a trace of disappointment. ‘Oh, no,’ she said. ‘I expect she’s far too young to pay much heed. But I like to talk to her and show her things. She will learn soon enough.’

‘It won’t be for lack of teaching if she does not,’ I said drily.

Celia glanced at me and registered the tone of my voice.

‘You don’t … you don’t regret it, Beatrice?’ She stepped towards me, the baby against her shoulder. Her face showed concern for me and my feelings, but I noticed she had tightened her grip on the baby’s shawl.

‘No.’ I smiled at her suddenly scared face. ‘No, no, Celia. The baby is yours with my blessing. I only spoke thus because I am surprised to see how much she means to you.’

‘How much?’ Celia stared at me, uncomprehending. ‘But, Beatrice, she is so utterly perfect. I would have to be mad not to love her more than my life itself.’

‘That’s settled then,’ I said, glad to let the matter drop. It seemed odd to me that Celia’s instinctive, passionate love for the child, which had started at the news of my pregnancy, had flowered into such devotion. My enthusiasm for the boy I dreamed I carried blinded me to the prettiness of the girl who was born. But then Celia had wanted a child to love, any child. I wanted only an heir.

I got up and strolled across the gently rocking deck to gaze across the sea to England, which was becoming a darker smudge every moment. I leaned against the ship’s rail and felt, half consciously, the sun-warmed wood pressing against my breasts. Tonight, or at the latest tomorrow night, I should be in the arms of the Squire of Wideacre once more. I shivered with anticipation. It had been a long, long wait but my homecoming to Harry would make up for it.

The wind veered to an offshore breeze, the sails flapped and the sailors cursed as we neared land. The captain at dinner promised we would dock at Portsmouth in the morning. I dipped my head over my plate to hide the disappointment in my face but Celia smiled and said she was glad.

‘For Julia is most likely to be awake then,’ she explained. ‘And she is always at her best in the mornings.’

I nodded, my eyelashes hiding the contempt in my eyes. Celia might think of nothing but the infant, but I would be surprised if Harry so much as glanced in the expensive cradle when I was standing by it.

I was surprised.

I was bitterly surprised.

We came to Portsmouth harbour shortly after breakfast, and Celia and I were standing at the ship’s rails anxiously scanning the crowd.

‘There he is!’ called Celia. ‘I can see him, Beatrice! And there is your mama, too!’

My eyes hit Harry’s gaze with a shock like a horse shying. I held to the rail, my nails digging into the hard wood to stop myself from crying, ‘Harry! Harry!’ and stretching my arms out to him to bridge the narrowing gap between ship and shore. I gasped with the physical pain of demanding, hard sexual desire. I glanced beyond him to Mama leaning forward to look out of the carriage window and raised a hand to her, then found my eyes dragged back to my brother, my lover.

He was the first up the gangplank as soon as the ship was moored and I was first to greet him – no thought of precedence in my head. Celia was bent over the cradle collecting her baby anyway, so there was no reason why I should hang back, and no reason why Harry should not take me into his arms.

‘Harry,’ I said, and I could not keep the lust from my voice. I held out my hands to him and raised my face for a kiss. My eyes ranged over his face as if I wanted to devour him. He dropped a brief affectionate kiss off-centre on my mouth and looked over my shoulder.

‘Beatrice,’ he said. And then looked back to my face. ‘Thank you, indeed I do thank you for bringing them home, for bringing both of them home.’

Then he gently, oh so gently, set me aside with an unconscious push and walked past me – the woman he adored – to Celia. To Celia and my child he went, and put his arms around both of them.

‘Oh, my dearest,’ I heard him say softly, for her ears alone. Then he plunged his face under her bonnet and kissed her, oblivious of the smiling sailors, of the crowd on the harbour wall, oblivious, too, of my eyes boring into his back.

One long kiss and his eyes were bright with love, fixed on her face and his whole face was warm with tenderness. He turned to the baby in her arms.

‘And this is our little girl,’ he said. His voice was full of surprise and delight. He took her gently from Celia and held the little body so the wobbly head was level with his face.

‘Good morning, Miss Julia,’ he said in a tender play. ‘And welcome home to your own country.’ He broke off and said aside to Celia, ‘Why, she is the image of Papa! A true Lacey! Don’t you think so? A very true-bred heir, my darling!’ And he smiled at her and, tucking the baby securely in the crook of his elbow, freed one hand so he could take her little hand and kiss it.

Jealousy, amazement and horror had first of all nailed me silent to the rail, but I found my tongue at last to break up this affecting scene.

‘We must get the bags,’ I said abruptly.

‘Oh, yes,’ said Harry, not shifting his gaze from Celia’s deliriously crimsoning face.

‘Will you fetch the porters?’ I said, as politely as I could.

‘Oh, yes,’ said Harry, not moving an inch.

‘Celia will want to greet Mama and show her the baby,’ I said skilfully and watched Celia’s immediate guilty jump and scurry to the gangplank with the child.

‘Not like that,’ I said impatiently, and called the nurse to carry the baby, straightened Celia’s bonnet and shawl, handed her her reticule and went with them, in a dignified procession, ashore.

Mama was as bad as Harry. She hardly saw Celia or me. Her arms were out for the baby and her eyes were fixed on its perfect little face, framed in the circle of pleats of the bonnet.

‘What an exquisite child,’ Mama said, her breath a coo of pleasure. ‘Hello, Miss Julia. Hello. Welcome to your home, at last.’

Celia and I exchanged knowing glances. Celia might be baby-struck but she had walked all night with the child almost every night since the birth. We maintained a respectful silence while Mama cooed and the baby gurgled in reply, while Mama inspected the tiny perfect fingers and held the satin-slippered feet with love. She raised her head at last and acknowledged us both with a warm smile.

‘Oh, my dears, I can hardly tell you what pleasure it gives me to see you both!’ As she said the words her eyes cleared of her passion for the baby and I saw some shadow pass over their pale blueness. She looked quickly, sharply, even suspiciously from Celia’s open flower-like face to my lovely lying one.

I felt suddenly, superstitiously afraid. Afraid of her knowledge, of her awareness. She knew the smell of birth, and I still bled in secret, a strange, sweet-smelling flow that I feared she could sense. She could not know; yet as she looked so hard at me I felt half naked, as if she was noting the new plumpness of my neck, of my breasts, of my arms. As if she could see beneath my gown the tight swaddling around my breasts. As if she could smell, despite my constant meticulous bathing, the sweet smell of leaking milk. She looked into my eyes … and she knew. In a brief exchange of silent looks she knew. She saw, I swear she saw, a woman who had shared a woman’s pains and pleasure, who had, like her, given birth to a child; who knew, like her, the pain and the work and the triumph of pushing out, into the uninterested world, a magical new life that you have made. Then she looked hard at Celia and saw a girl, a virginal pretty girl, quite unchanged from the shy bride. Virtually untouched.

She knew, I could sense it. But her mind recoiled. She could not put the knowledge into her conventional frightened mind that her instincts were telling her as clear as a ringing bell. Her eyes saw my plumpness and Celia’s strained thinness. Her senses smelted the milk on me; her own motherhood recognized that mark on me: a woman who has given birth, who has taken her part in the creation of life, and her eyes slid from me to Celia.

‘How tired you must be, my dear,’ she said. ‘Such a long journey after such an experience. Sit down and we will soon be home.’ Celia had a kiss and a seat beside Mama in the carriage, and then Mama turned to me.

‘My dearest,’ she said, and the fear and unspeakable suspicion in her eyes had gone. She was too weak, she was too much of a coward to face anything unpleasant; the secret horror of her life would always escape her. ‘Welcome home, Beatrice,’ she said, and she leaned forward and kissed me, and held my plump fertile body in her arms. ‘It is good to see you again, and looking so well.’

Then Harry joined us and he and I loaded the failing wet-nurse into Mama’s carriage, and watched the luggage and the servants into the second chaise.

‘How well you have managed,’ said Harry gratefully. ‘If I had known when I left you … But I never should have gone at all if I had not known that you would manage, my dearest Beatrice, whatever happened.’

He took my hand and kissed it, but it was the cool kiss of a grateful brother and not the warm caress he had given to Celia. I scanned his face, searching for a clue to his change towards me.

‘You know I would always do anything to please you, Harry,’ I said ambiguously, the heat still in my body.

‘Oh, yes,’ he said equably. ‘But any man would feel the care of his child, his very own child, to be something special, so precious, Beatrice.’

I smiled then. I could see into his heart. Harry, like Celia, was baby-struck. It would be a tedious period while it lasted but they would grow out of it. I very much doubted if Harry’s infatuation would last the length of the journey home, cooped up in a carriage with a squalling, underfed, travelsick baby, an inexperienced mother and a foreign nurse.

But I was wrong.

It lasted the long journey. Their passion for the baby proved so demanding that the journey took long extra hours while the coach dawdled at walking speed behind Harry and Celia who believed the infant’s travelsickness would be relieved by a walk in the fresh air. I strolled ahead. Mama stayed, imperturbable, in the coach.

Despite my rising irritation with Harry, I could be angry with no one when I walked in the lanes of Wideacre with the great chestnut trees showering crimson and white petals on my head from their fat candle flowers. The grass grew so green – so brilliant a green it made you thirsty for the rain that had made it that astonishing colour. Every hedge was bright with greenness, every north-facing tree trunk was shadowed with the deep wet greenness of moss or the grey of fat lichen. The land was as wet as a sponge. All along the hedgerows there were the pale faces of the dogroses and the white flowers of the blackberry bushes. In the better cottages, vegetables were thriving and flowers edging the garden paths made even the smallest houses look bright and prosperous. The grass, the pathways, even the walls were speckled with summer flowers growing with irresistible joy in the cracks and crannies.

Yes, Harry and I had a score to settle. No man would walk past me to another woman and not regret it, but on that long, slow journey home I felt, as I felt for the rest of the summer, that I first had to come home to Wideacre; that Harry was the least important issue in this homecoming. That Harry and I could wait until I had met the land again.

Come home I did! I swear not a cottage on our estate but I banged on the door and pushed it open and smiled, and took a cup of ale or milk. There was not one house but I inquired after children, and checked profits with the men. Not one new hayrick did I miss, not one springing field with the soil so rich and wet did I neglect. Not even the seagulls wheeling above the ploughshares saw more than me. My horse was at the door every morning, and while Harry was up early keeping baby hours, I was off to brood like a laying hen over the land.

I loved it still – infinitely more now that I had been elsewhere, now that I had seen the pitiful dry French farms and the ugly rows of vines. I loved every fresh, easy fertile acre of it and I loved the difficult hill fields and the plough-free downs as well. Every day I rode and rode until I had quartered the estate like a hunting barn owl and marched its borders as if it were Rogation Day every day.

Mama protested, of course, at my riding out without a groom. But I had unexpected allies in the happy couple.

‘Let her go, Mama,’ said Harry easily. ‘Beatrice is beating the bounds; she’s been long away. Let her go. She’ll take no harm.’

‘Indeed,’ Celia assented in her soft voice. ‘Indeed she deserves a holiday after all she has done.’

They smiled on me, the soft foolish smile of doting parents, and I smiled back and was off. Every step of the paths, every tree of the woods I inspected, and I never rested for one day until I knew I had the estate firmly back in my hand.

The estate workers welcomed me back like á lost Stuart prince. They had dealt with Harry well enough for he was the Master in my absence, but they preferred to speak to me, who knew, without being told, who was married to whom, who was saving a dowry and who could never marry until a debt was paid. It was easier to talk to me for so little needed saying, while Harry, in his awkward, helpful way, would embarrass them with questions where silence would have been better, and with offers of help that sounded like charity.

They grinned slyly when they confided that old Jacob Cooper had a brand-new thatch on his cottage, and I knew without being told more that the reeds would have been cut, without payment, from our Fenny. And when I heard that it had been a remarkably bad year for pheasants, hare and even rabbits, then I knew without being told that they had all taken advantage of my absence to be out with their snares and their dogs. I smiled grimly. Harry would never see such things for he never noticed our people as people. He noticed the tugged forelock, but never saw the ironic smile beneath. I saw both, and they knew it. And they knew when I nodded my head that the sparkle in my eyes was a warning against any one of my people overstepping the line. So we all knew where we were. I was home to take the estate, the people, and every greening shoot back in my hand. And it seemed to me, on every hard daily ride, that the estate, the people and even the greening shoots were better for my return.

I rode everywhere – down to the Fenny to see the marshy water-meadow where the yellow flags were blooming, rooted into the two crumbled walls that were all that remained of the derelict mill. My horse was knee-deep as I urged her up to look. The building where a girl and a lad had lain and talked of love would never shelter lovers again.

It seemed so very long ago now that it felt as if it had happened to someone else, or that I had dreamed it. It could not have been me that Ralph had loved and romped with and rolled with and ordered and plotted with and risked his life for. That Beatrice had been a beautiful child. Now I was a woman afraid neither of the past nor of the future. I gazed unemotionally at the ruined barn, and at the new marshy empty meadow and was glad to feel nothing. Where there had been regret and fear there was now an easy sense of distance. If Ralph had survived, even if he had survived to lead a gang of rioters, he would be far away by now. Those days on the downs and the secret afternoons in the mill would be almost forgotten to him, as they were to me.

I turned my horse homewards and trotted through the sunny woods. The past was behind me, the River Fenny flowed on. I had a future to plan.

I started with my own quarters. The builders had finished in the west wing and it was ready for me. The lovely heavy old furniture, which had been exiled from Harry’s bedroom on his return from school to his mock-pagoda, had been bundled into a lumber room at the top of the house, and I had it taken out and polished until it gleamed with the deep shine of Jacobean walnut. Knobby with carving, so heavy it took six sweating men to carry it. ‘So ugly!’ said Celia in gentle wonderment. It was the furniture of my childhood and I felt a room was insubstantial without it. The great carved bed with the four posts, as thick as poplar trunks, with the carved roof above, I moved to my bedroom in the west wing.

Now I had a room that looked out on the front not the side of the house and I could see from my window the rose garden, the paddock, our wood and the lovely crescent of the downs rising behind it all. The carved chest stood beside it, and a great heavy press for my dresses loomed in the adjoining dressing room.