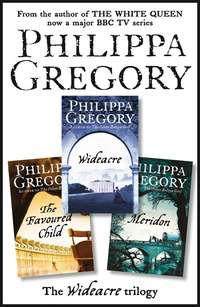

The Complete Wideacre Trilogy: Wideacre, The Favoured Child, Meridon

I fell silent. I had said more than I had meant to. I felt at once foolish, and perilously exposed. My fingers still twirled the glass and I kept my eyes down on them. Then they were stilled, as John put his pale-skinned hand over them.

‘I will never take you away, Beatrice,’ he said tenderly. ‘I do indeed understand how your life is here. It is a tragedy for you, I think, not to have been born the heir to the land. But I do see how you are indispensable on the estate. I hear on all sides how well you manage it, how you change Harry’s plans so that they work in practice as well as in theory. How you never give charity, but always give help. How the land and the people who work the land benefit over and over again from your passion. And so I pity you.’ My head jerked up in instinctive contradiction, but my protest was stilled by his gentle smile. ‘Because you can never possess your beloved Wideacre. I will never come between you and your control of the land, but I am unable, no one is able, to make the land you love absolutely yours.’

I nodded. A few pieces of the puzzle of my new husband had fallen into place. His understanding of what Wideacre meant to me had prompted his agreement to our living in the west wing. His understanding of my obsession had led him to disregard my first refusal. He knew we could be lovers. He knew we could be married. He knew that one of the greatest things in his favour was that he owned no land, no house of his own where I would have had to go. He knew also, for he was so good, this serious, quizzical, desirable husband of mine, that his smile set my pulse thudding, and when he touched me, I melted.

I had never slept all night with a lover in one bed without fear of morning, and that was good for me. But best was his desire, which drew him to me for more times than I could remember in a hazy night of pleasure and wine and talk and laughter.

‘Ah, Beatrice,’ said John MacAndrew, pulling my head on to his shoulder with tender roughness. ‘It’s a long while I’ve been waiting for you.’

And so we slept.

And in the morning, over the fresh-baked rolls and the strong coffee, he said, ‘Beatrice, I think I may like being married to you.’ I found then that my smile was as warm and spontaneous as his own, and that the warmth on my face was a blush.

So the first days of married life passed as easily, as tenderly, and as full of delight, as the first months, aided by our mutual desire. John had had other lovers (and, God knows, so had I), but together we found something special. A mixture of tenderness and sensuality made our nights sweet. But our days were special because of his quick wits and his utter refusal to cease laughing: at me, with me, because of me. He could set me laughing at the most inappropriate moments: when faced with a rambling complaint from old Tyacke, or when listening to some mad scheme of Harry’s. Then I would glance past Tyacke to see John pulling his forelock to me in burlesque imitation of respect, or see him nodding enthusiastically behind Harry’s back while Harry outlined an insane plan to build massive glass-houses to grow pineapples for London.

At times like that, and they came every sweet cold wintry day, I would feel that we had been married and happy for years, and that the future stretched before us like easy stepping stones across a slow river.

Christmas came round and the tenants were bidden to the traditional party. The biggest houses in the land let the tenants and labourers watch the Quality feasting and dancing, but the Wideacre tradition is that of a manor farm. We set up great trestle tables and benches in the stable yard, and we build a great bonfire and roast whole oxen. After everyone has eaten well, and drunk deep of Wideacre-brewed ale, we push the tables back, throw off the winter wraps and dance in the pale winter sunshine.

This party, the first since Papa’s death, was held under the clear blue sky of a good winter’s day, and we danced all afternoon with sunshine warm on our cheeks. As the bride, it fell to me to lead the set and with a half-apologetic smile at John I claimed Harry’s hand for the dance. Behind us the set formed, mimicking our handclasp. Behind us, as well, formed the traditions I had meant to set: that the Squire and his beautiful sister always led the Christmas dance in the stable yard. The next couple was Celia, looking breathtakingly pretty in royal blue velvet trimmed with white swan’s down, and my darling John, ready with a gentle word for Celia and a private smile for my eyes alone.

They started the music. Nothing special: a fiddle and a bass viol, but it was a fast merry tune and my crimson skirts swirled and swayed as I twirled one way, then another, and then clasped Harry’s two firm hands and romped down the avenue of faces. Harry and I stood at the bottom making an archway with our arms and the rest of the set danced through. Then we became part of the smiling, clapping corridor for Celia and John.

‘Are you happy, Beatrice? You look it,’ called Harry to me, watching my smiling face.

‘Yes, Harry, I am,’ I said emphatically. ‘Wideacre is doing well, and we are both well married. Mama is content. I have nothing left to wish for.’

When Harry’s smile widened, his face, increasingly plump from the offerings of Celia’s cook, became even more complacent.

‘Good,’ he said. ‘How well everything has turned out for us all.’

I smiled, but did not reply. I knew he was reminding me of my early opposition to the idea of marriage with John. Harry had never understood why my utter refusal had turned into smiling consent. But I knew he was also thinking of my promise and threat that I would be on Wideacre, at his side, for ever. Harry both dreaded and longed for time alone with me in the locked room at the top of the west-wing stairs. However loving he found Celia, however full his life, he would always long for that secret perverse pleasure waiting for him beyond the light of the chandeliers, beyond the usual halls and corridors of the house. Since my marriage I had met Harry in secret there perhaps two or three times. John accepted easily my excuse of late work, and he himself sometimes stayed overnight with patients if he anticipated a painful birth or a difficult death. During those times, while he waited and watched with the birthing and the dying, I strapped my brother to the wall and ill-treated him in every way I could imagine.

‘Yes, it is good,’ I agreed.

It was our turn to gallop down the set. We had risen to the head again while we were talking, and again we clasped hands and danced down the line. As we reached the end the musicians rippled a chord signifying the end of that dance and Harry spun me round and around so that my crimson brocade skirts flew out in a blaze of colour. I was unlucky – the dizziness tipped me from elation to nausea, and I broke from him white-faced.

John was at my side in an instant. Celia, attentive, beside him.

‘It is nothing, nothing,’ I gasped. ‘I should like a glass of water.’

John snapped his fingers peremptorily to a footman and the icy water in a green wine glass washed down the taste of rising bile, and I cooled my forehead on the glass. I managed a cheeky smile at John.

‘Another miracle cure for the brilliant young doctor,’ I said.

‘It’s as well I have the cure, since I think I provided the cause,’ he said in a low warm voice. ‘There’s been enough dancing for you for one day. Come and sit with me in the dining room. You can see everything there, but you may dance no more.’

I nodded, and took his arm into the house, leaving Celia and Harry to head the next set. John said not a word until we were seated by the window that overlooked the yard, with a pot of good strong coffee beside us.

‘Now, my pretty tease,’ he said, handing me a cup just as I liked it, without milk and with lots of brown treacly sugar. ‘When are you going to condescend to break the good news to your husband?’

‘What can you mean?’ I asked, widening my eyes at him in mock naivety.

‘It won’t do, Beatrice,’ he said. ‘You forget you are talking to a brilliant diagnostician. I have seen you refuse breakfast morning after morning. I have seen your breasts swelling and growing firm. Don’t you think that it’s about time you yourself told me what your body has already said?’

I shrugged negligently, but beamed at him over my cup.

‘You’re the expert,’ I said. ‘You tell me.’

‘Very well,’ he said. ‘I think it well we married speedily! I anticipate a son. I think he will arrive at the end of June.’

I bowed my head to hide the relief in my eyes that he had no doubt that I had conceived on that one occasion before our marriage, and no idea that the child was due in May. Then I looked up to smile at him. He was not Ralph. Nor was he the Squire. But he was very, very dear to me.

‘You are happy?’ I asked. He moved from his chair to kneel beside mine and slide his arms around my waist. His face nuzzled into my warm perfumed neck and into the fullness of my breasts – pushed up by the unbearably tight lacing of my stays.

‘Very happy,’ he said. ‘Another MacAndrew for the MacAndrew Line.’

‘A boy for Wideacre,’ I corrected him gently.

‘Money and land then,’ he said. ‘That’s a strong combination. And beauty and brains as well. What a paragon he will be!’

‘And a month early for the conventions!’ I said carelessly.

‘I believe in the old ways,’ said John easily. ‘You only ever buy a cow in calf.’

I had worried about telling him, but no shadow ever came into his mind, not in that first tender moment, nor at any later time. When he discovered how tight I was laced and insisted that I came out of my stays, he merely teased me for my size – he never dreamed that I was five weeks further on in my pregnancy than our lovemaking before the fire would have allowed. All through the icy cold winter when my body was burning at night and so firmly rounded, he merely enjoyed my happiness, and my confident, daring sensuality without question.

No one questioned me. Not even Celia. I announced that the baby would be born in June, and we booked the midwife as if she would be needed then. Even when the long icy winter turned green I remembered to hide my rising fatigue and pretend I was blooming with mid-pregnancy health. And a few weeks after the first secret movement I clapped my hand to my belly to say, in an awed whisper, ‘John, he moved.’

I was aided in the deception by John’s own ignorance. He might have been qualified at the first university in the country, but there were no women of Quality who would allow a young gentleman near them at such a time. Those who preferred a male accoucheur would choose an old, experienced man, not the dashing young Dr MacAndrew. But the majority of ladies and women of the middling sort held to the old ways and used the midwives of the district.

So the only pregnancies John had supervised were those of the poorer tenant farmers and working women, and those only by chance. They would not call him in, fearing the cost of professional fees, but if he was in a Quality house visiting a sick child, the Lady of the house might mention that one of the labourers’ wives was having a difficult birth, or that one of the parlourmaids was pregnant. So John saw births only where there were grave dangers, and only those of poor women. And while he looked at me with his tender sandy-lashed gaze I was able to lie, with all my experience, with all my skill, and with a silly hope of keeping our happiness safe: to keep things as tender and as loving as they were.

Love him I did, and if I wanted to keep his love he would have to be out of the way when the child he thought was his was born, supposedly five weeks premature.

‘I should so like to see your papa here again,’ I said conversationally one evening, while the four of us were seated around the fire in the parlour. Although the blossom glowed in the trees and the hawthorn was white in the hedges, it was still cold after sunset.

‘He might come for a visit,’ said John dubiously. ‘But it’s the devil’s own job detaching him from his business. I nearly had to go and drag him away by the coat-tails in time for the wedding.’

‘He would surely like to see his first grandchild,’ said Celia helpfully. She leaned towards the ever-open workbox, which stood between us, and selected a thread. The altar cloth was half completed and I was employed in stitching in some blue sky behind an angel. A task not even I could spoil, especially since I made one stitch and laid down the work every time I wanted to think or speak.

‘Aye, he’s a family man. He would fancy himself the head of a clan,’ John said agreeably. ‘But I would have to kidnap him to get him away from the business during the busiest time of year.’

‘Well, why don’t you?’ I said, as if the idea had, that second, struck me. ‘Why do you not go and fetch him? You said yourself you were missing the sweet smells of Edinburgh – Auld Reekie! Why not go and fetch him? He can be here for the birth and stand sponsor at the christening.’

‘Aye.’ John looked uncertain. ‘I would like to see him, and some colleagues at the university. But I would rather not leave you thus, Beatrice. And I would rather make a visit later when we could all go.’

I threw up my hands in laughing horror.

‘Oh, no!’ I said. ‘I have travelled with a newborn child already. I shall never forgive Celia for that trip with Julia. Never again will I travel with a puking baby. Your son and I shall stay put until he is weaned. So if you want to visit Edinburgh inside two years, it had better be now!’

Celia laughed outright at the memory.

‘Beatrice is quite right, John,’ she said. ‘You can have no idea how dreadful it is travelling with a baby. Everything seems to go wrong, and there is no soothing them. If you want your papa to see the baby it will have to be him who comes here.’

‘You’re probably right,’ said John uncertainly. ‘But I would rather not leave you during your pregnancy, Beatrice. If anything went wrong I would be so far away.’

‘Ah, don’t worry,’ said Harry comfortingly from the deep winged chair by the fireplace. ‘I will guarantee to keep her off Sea Fern and Celia can promise to keep her off sweetmeats. She will be safe enough here, and we can always send for you if there is any trouble.’

‘I should like to go,’ he confessed. ‘But only if you are sure, Beatrice?’ I poked my needle in an embroidered angel’s face to free my hand to hold it out to him.

‘I am sure,’ I said, as he kissed it tenderly. ‘I promise to ride no wild horses, nor get fat, until you return.’

‘And you will send for me if you feel in the least unwell, or even just worried?’ he asked.

‘I promise,’ I said easily. He turned my hand palm up, in the pretty gesture he had used in our courtship, and pressed a kiss into it, and closed my fingers over the kiss. I turned my face to him and smiled with all my heart in my eyes.

John stayed only for my nineteenth birthday on the fourth of May when Celia had the dining room cleared of furniture and invited half-a-dozen neighbours in for a supper dance to celebrate. More tired than I cared to show, I danced two gavottes with John and a slow waltz with Harry before sitting down to open my presents.

Harry and Celia gave me a pair of diamond ear-drops, Mama a diamond necklace to match. John’s present was a large heavy leather box, as big as a jewel case with brass corners and a lock.

‘A mineful of diamonds,’ I guessed, and John laughed.

‘Better than that,’ he said.

He took a little brass key from his waistcoat pocket and handed it to me. It fitted the lock and the lid opened easily. The box was lined with blue velvet, and nestling securely in its bed was a brass sextant.

‘Good heavens,’ said Mama. ‘What on earth is it?’

I beamed at John. ‘It is a sextant, Mama,’ I said. ‘A beautiful piece of work and a wonderful invention. With this I can draw my own maps of the estate. I won’t have to rely any more on the Chichester draughtsmen.’ I held out my hand to John. ‘Thank you, thank you, my love.’

‘What a present for a young wife!’ said Celia wonderingly. ‘Beatrice, you are well suited. John is as odd as you!’

John chuckled disarmingly. ‘Oh, she’s so spoiled I have to buy her the strangest things,’ he said. ‘She’s dripping with jewels and silks. Look at this pile of gifts!’

The little table in the corner of the dining room was heaped with brightly wrapped presents from the tenants, workers and servants. Posies of flowers from the village children were all around the room.

‘You’re very well loved,’ said John, smiling down at me.

‘She is indeed,’ said Harry. ‘I never get such a wealth of treats on my birthday. When she’s twenty-one I shall have to declare a day’s holiday.’

‘Oh, a week at least!’ I said, smiling at the hint of jealousy in Harry’s voice. Harry’s summer as the pet of the estate had come and gone too quickly for him. They had taken him to their hearts that first good harvest, but when he had come home from France they had found that the Squire without his sister was only half a Master, and a silly, irresponsible half at that.

My return from France had been a return into pride of place and the presents and the deep curtsies, bows, and loving smiles were the tribute I received.

I crossed to the table and started opening the gifts. They were small, home-made tokens. A knitted pin cushion with my name made out of china-headed pins. A riding whip with my name carved on the handle. A pair of knitted mittens to wear under my riding gloves. A scarf woven from lamb’s wool. And then a tiny package, no bigger than my fist, wrapped, oddly, in black paper. There was no message, no sign of the sender. I turned it over in my hands with an uneasy sense of disquiet. My baby stirred in my belly as if he felt some danger.

‘Open it,’ prompted Celia. ‘Perhaps it says inside who has sent it to you.’

I tore the black paper at the black seal, and out of the wrapping tumbled a little china brown owl.

‘How sweet,’ said Celia readily. I knew I was staring at it in utter horror and tried to smile, but I could feel my lips trembling.

‘What is the matter, Beatrice?’ asked John. His voice seemed to come from a long way off; when I looked at him I could hardly see his face. I blinked and shook my head to clear the fog and the buzzing sound in my ears.

‘Nothing,’ I said, my voice low. ‘Nothing. Excuse me one minute.’ Without a word of explanation I turned from the pile of unopened gifts, and left my birthday party. In the hall, I rang the bell for Stride. He came from the kitchen doors smiling.

‘Yes, Miss Beatrice?’ he said.

I showed him the black wrapping paper balled in my hand, I had the little china owl tight in the other hand. I could feel the coldness of the porcelain and it seemed to make me shiver all over.

‘One of my presents was wrapped in this paper,’ I said abruptly. ‘Do you know when it was delivered? How it came here?’

Stride took the crumpled paper from me and smoothed it out.

‘Was it a very little package?’ he asked.

I nodded. My throat was too dry to trust my voice.

‘We thought it must have been one of the village children,’ he said with a smile. ‘It was left under your bedroom window, Miss Beatrice, in a little withy basket.’

I gave a deep shuddering sigh.

‘I want to see the basket,’ I said. Stride nodded, and went back through the green baize door. The coldness of the little owl seemed to chill me through and through. I knew well enough who had sent it. The crippled outlaw who was all that was left of the lad who had given me a baby owl with such love four years ago. Ralph had sent me this ominous birthday gift as a signal. But I did not know what it meant. The dining room door opened, and John came out exclaiming at my white face.

‘You are overtired,’ he said. ‘What has upset you?’

‘Nothing,’ I said again, framing the word with numb lips.

‘Come and sit down,’ he said, drawing me into the parlour. ‘You can go back to the dancing in a minute. Would you like some smelling-salts?’

‘Yes,’ I said, to be rid of him for a moment. ‘They are in my bedroom.’

He scanned my face, and then left the room. I sat cold and still and waited for Stride to bring me the little withy basket.

He put it in my hands and I nodded him from the room. It was Ralph’s work, a tiny replica of the other basket I had pulled up to my window seat in the dawn light on my fifteenth birthday. The reeds were fresh and green, so it had been made in the last few days. Wideacre reeds perhaps, so he could be as close to the house as the Fenny. With his basket in one hand, and his horrid little present in the other, I gave a moan of terror. Then I bit the tip of my tongue and pinched my cheeks with hard fingers to fetch some colour to them, and when John came back into the room with my smelling-salts I had a hard laugh ready, and I waved them away. Smelling-salts, questions, grave looks of concern, I dismissed airily. John watched me, his eyes sharp and anxious, but he pressed no questions on me.

‘It is nothing,’ I said. ‘Nothing. I just danced too much for your little son.’ And I would say no more.

I dared not give him reason to stay. With my baby due in three or four weeks, I had to have him away. So I hid my fear under a bright brave front, and I packed his bags for him with a light step and an easy smile. Then I stood on the steps and waved his chaise out of sight, and I did not let myself tremble for fear until I had heard the hoofbeats of the horses cantering away down the drive.

Then, and then only, I leaned back on the sun-warmed doorpost and moaned in fright at the thought of Ralph daring enough to ride or, even more hideous, to crawl right up to the walls of the Hall, and hating enough to remember what he had given me for a present four years before.

But there was no time for me to think, and I blessed the work and the planning that I had to do, and my tiredness during the days and my heavy sleep at nights. In my first pregnancy I had revelled in slothful inactivity in the last few weeks, but in this one I had to pretend to three pairs of watchful eyes that I was two months away from my time. So I walked with a light step and worked a full day, and never put my hands to my aching back and sighed until my bedroom door was safely shut and I could confess myself bone-tired.

I had expected the birth at the end of May, but the last day of the month came and went. I was so glad to wake to the first of June. It sounded, somehow, so much better. I recounted the weeks on my fingers as I sat at my desk with the warm sun on my shoulders and wondered if I should be so lucky as to have a late baby who hung on to make my reputation yet more secure. But even as I reached for the calendar a pain gripped me in the belly, so intense that the room went hazy and I heard my voice moan.

It held me paralysed for long minutes until it passed and then I felt the warm wetness of the waters breaking as the baby started his short perilous journey.

I left my desk and tugged one of the heavy chairs over to the tall bookcase where I keep the record books that date back to the Laceys’ first seizure of the land seven hundred years ago. I had rather feared that it would hurt me to climb on to the seat and to stretch up to the top shelf. And I was right. I gasped with the pain of stretching and tugging at the heavy volumes. But the scene had to be set, and it had to be persuasive. So I pulled down three or four massive old books and dropped them picturesquely around the chair on the floor. Then I turned the chair over with a resounding crash and lay down on the floor beside it.

My maid, tidying my bedroom above, heard the noise of the falling chair and tapped on the door and came in. I lay as still as the dead and heard her gasp of fright as she took in the scene: the overturned chair, the scatter of books and the widening stain on my light silk skirt. Then she bounded from the room and shrieked for help. The household exploded into panic and I was carried carefully and tenderly to my bedroom where I regained consciousness with a soft moan.