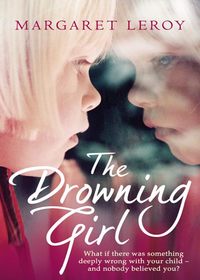

The Drowning Girl

We order guinea fowl with polenta, and talk about ourselves—inconsequential things to start with, music we like, places we’ve been. Matt seems to have travelled everywhere: India, Peru: Namibia—where he hiked down the Fish River Canyon. I have to confess that I’ve only been to Paris, on a school trip. But maybe he enjoys this discrepancy, the way it makes him seem a man of the world.

I note the things I like about him, ticking off the boxes—his clean smell of cologne and ironed linen, the fringe that falls over his face. I briefly remember when Dominic first took me to the Alouette: how he held my gaze, and I knew he could see it all in my face, so nakedly, and I knew we were there already. I push the thought away. I tell myself it doesn’t have to be an instant thing.

Matt refills my glass. I feel drunk already, high on the shiny hopefulness of the evening. The guinea fowl is delicious, with a rich, dark, subtle gravy. We eat appreciatively. A little silence falls.

‘Your daughter,’ he says then, tentatively. ‘Is the guy—I mean, is he still on the scene?’

‘I had an affair with someone,’ I tell him. Trying to sound casual. ‘A much older man. He was married.’

‘And now?’ he says delicately.

‘He’s in the past,’ I tell him. Very deliberate, definite. Tonight I mean it, I’m certain. ‘I was terribly young when I met him.’

‘Yes,’ he says. Perhaps a little too readily for my liking, as though he can easily imagine me being terribly young. ‘And anyone since then?’

I don’t know if I should pretend. Is four years a very long time to go without a man? Will he think me strange?

‘No, nobody since,’ I tell him.

‘You must be very strong,’ he says. ‘Bringing up your daughter on your own.’

‘I don’t feel strong,’ I tell him.

‘I guess it’s lonely sometimes,’ he says.

‘We manage—but, yes, it can be lonely,’ I tell him.

And I see in that moment—that, yes, I’m lonely, but maybe I don’t have to be alone. That it isn’t for ever, this sense of restriction I have, of walls that press in whichever way I turn. That it could all be different.

‘I can feel that in you, that you’ve been hurt,’ he says.

He puts his hand on mine. It feels pleasant, reassuring.

‘And you?’ I say. Deliberately vague.

‘I lived with a woman for a while,’ he tells me.

He takes his hand away from me. He moves things around on the table—the salt cellar, the bottle of wine—as if he’s playing a game on an invisible board.

‘What happened?’ I ask him.

He slides one finger around the rim of his glass.

‘I travel a lot on business,’ he says. ‘And there was this weird thing. That when I was away from her, I used to long to be with her—just yearn to be back home with her. I’d get obsessed, I couldn’t think of anything else.’

‘I can understand that,’ I tell him warmly. Knowing about obsession.

‘But when I got back I used to find she wasn’t how I’d thought. It would happen so quickly. We’d row again, and everything would annoy me. There were things she did that would get right under my skin. Stupid things. Like, she used to eat lots of apples and leave the cores on the floor…’

I make empathic noises. Resolving that from now on I will always bin my apple cores immediately.

He looks down for a moment, flicking some lint from his sleeve.

‘It’s strange, isn’t it?’ he says. ‘Like you can only love the person when you’re miles away from them. Like it’s just a dream you have…’

We move on to easier things—our families, where we come from. He leans across the table towards me, his gaze caressing my face. Over the white chocolate pannacotta, I feel a little shimmer of arousal.

We go out to his car. It’s a frosty evening, with spiky bright stars in an indigo sky. Our breath is white. He’s parked by the river, where swans move pale and silent against the crinkled dark of the water, and there are dinghies tied up: you can hear the gentle jostling of the water against their hulls.

‘Thank you. That was a wonderful evening,’ I tell him.

‘Yes, it was,’ he says.

At his car he doesn’t immediately take out his key. He turns towards me, putting one hand quite lightly on my shoulder.

‘Grace. I’d like to kiss you.’

‘Yes,’ I say.

He presses his hands to the sides of my face and moves my face towards him. He kisses my forehead, my eyelids, moving his lips on me very slowly, smoothing his fingers over my hair. I love his slowness; I feel a surge of excitement, the thin flame moving over my skin. I have my eyes closed; I can hear the sound of the water, and his hungry, rapid breath. When his lips meet mine I am so ready for him. He tastes of claret, he has a searching tongue. We kiss for a long time. He pulls me close: I feel his erection pressing against me.

Eventually, we move apart and get into the car. He turns on a CD—Nina Simone: the music is perfect, her voice smoky, confiding. He drives back towards my flat and neither of us says anything. Most of the time he rests one hand on my thigh. I feel fluid, open.

He turns into my road in Highfields and pulls in at the kerb.

‘You could come in,’ I tell him.

‘I’d like that very much,’ he says.

He wraps his arm around my waist as we walk towards my doorway, then slips his hand up under the blouse, sliding his fingers between the silk and my skin. I think of him moving his hands all over me, easing his fingers inside me.

I unlock the outer door. And then the sound assaults us, the moment the door swings open—a thin, shrill wailing. Matt moves a little away from me. I curse myself for inviting him in, but now it’s too late to turn back.

‘I’m so sorry,’ I tell him.

I push at the door to the living room. The crying slams into us, suddenly louder as the door swings wide. I sense Matt flinching. Well, of course he would.

Sylvie is on Karen’s lap, shuddering, gasping for breath, her face stricken. She turns her head as I go in, but she doesn’t stop sobbing. Karen has a tight, harassed look. The glittery glamour of Welford Place seems a world away now.

‘This is Matt—this is Karen. And Sylvie,’ I say, above the wailing.

Matt and Karen nod at one another. They have an uneasy complicity, like strangers thrown together at a crime scene. Nobody smiles.

‘She had a nightmare,’ says Karen. ‘I couldn’t settle her.’

Sylvie stretches her arms towards me. I kneel on the carpet and hold her on my lap. Her body feels brittle. She’s still crying, but quietly now. Karen stands and smoothes down her clothes, with an evident air of relief.

‘Can I make anyone a coffee?’ she says.

‘Please,’ I say for both of us.

Matt says nothing. He sits on the arm of the sofa, in a noncommittal way, so it’s not quite taking his weight.

Karen goes to the kitchen. Sylvie’s crying stops, as though it’s abruptly switched off. She clutches me, her body convulses; she vomits soundlessly all over the blue silk blouse.

‘Shit,’ says Matt, quietly.

He moves rapidly to the window, keeping his back to us. Karen comes, takes Sylvie’s shoulders, steers her to the bathroom.

‘I’ll clean her up.’ She’s definite, brisk. ‘You change.’

I feel a profound gratitude towards her.

I rush to the bedroom, unbutton the blouse, grab the first T-shirt I find.

Matt is standing in the hallway; he has his car keys ready in his hand.

‘I guess I’d better go, let you get on with it,’ he says.

‘You don’t have to leave,’ I tell him. ‘Really, you don’t have to.’

I glance down at the T-shirt I put on without thinking; it has a picture of a baby bird and says ‘Chicks Rule’.

‘No, really, I think I should,’ he tells me. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll see myself out.’

His face is a shut door.

‘Thanks for the evening, it was lovely,’ I say lamely.

He reaches out and touches my upper arm through the cloth of my T-shirt—tentatively, as though he’s afraid of what might come off on his hand.

‘It was great,’ he says heartily. ‘It was lovely to meet you, Grace. Look, I’ll be in touch.’

But we both know he won’t be.

I stand there, hearing him leave—the percussive sound of his feet on the pavement, the car door slamming, the hum of the engine as his car moves away. There’s such finality to all this, each sound like the end of a sentence. He drives off, out of my life. I guess that for him I am just another illusion: that like so much else in his life, I am not what he hoped for, not what he thought. Disappointment is a charred taste in my mouth. In the hallway I can still smell his cologne. It fills me with nostalgia already.

Karen has cleaned Sylvie up and found her a new pyjama top.

‘I’m so sorry,’ I tell her. It’s what I so often say to her. ‘I’ll get the blouse back to you just as soon as I’ve washed it.’

‘It’s handwash only.’ There’s a hard edge to her voice. ‘You might want to put some bicarb with it, to get rid of the smell.’

‘Yes. It’ll be good as new, I promise.’

I catch sight of myself in the mirror. I look all wrong in this jokey T-shirt with my hair up—as though I’m a teenager pretending to be a grown woman. I wrench the clip out of my hair.

CHAPTER 7

‘Ms Reynolds. Please come in.’

Her window looks over the garden. There was frost in the night; today there’s a thin yellow sunlight and the dazzle and shimmer of melting ice, and the grass is striped with the sharp straight shadows of trees. Children bundled in scarves and hats are playing on the climbing frame; you can hear their shouting and laughter.

I sit in front of her desk. There’s a pain in my jaw that I woke up with this morning, some kind of neuralgia probably. It nags at me; I wish I’d taken some Nurofen. The secretary brings the coffee tray. Mrs Pace-Barden pours coffee into a little gold-rimmed cup, and slides it across the desk towards me. My hands feel big and clumsy clasped around the tiny cup. She pours some for herself, but doesn’t drink it.

‘I’ve brought you in today,’ she says, ‘to have a little talk about Sylvie.’

She’s solemn, unsmiling, her forehead creased in a frown, but I tell myself this is good, that she’s taking Sylvie so seriously.

‘Yes,’ I say.

‘I have to tell you, we do find Sylvie’s behaviour very worrying.’

She has rather pale eyes, that are fixed on my face.

‘Yes, I know,’ I tell her.

I sip my coffee. It’s weak and bland but scalding hot because the milk was heated; it hurts my throat as I swallow it.

‘These tantrums she has—well, lots of children have tantrums, of course, we’re used to that… But not like Sylvie,’ she says.

She leaves a pause that’s weighted with significance. I don’t say anything.

‘My staff do find it very difficult,’ she says then. There’s a note of reproach in her voice. ‘When Sylvie has one of her tantrums, it takes the assistant’s total attention to settle her. Sometimes it takes an hour. And this is happening several times a week, Ms Reynolds.’

‘Yes. I’m sorry,’ I tell her.

‘And this phobia of water. D’you have any idea what started it?’

‘She’s always had it, really,’ I tell her. ‘It’s a fear of water touching her face. I mean, children are just frightened of things, aren’t they, sometimes? For no apparent reason?’

‘Of course. But Sylvie’s reaction is really very extreme. You see, Ms Reynolds, water-play is very much a part of the environment here. Most children love it. They find it relaxing.’

‘But couldn’t she be in another room or something?’

Her face hardens. Perhaps I sounded accusing.

‘We’re always careful that Sylvie is as far away as possible. But even that isn’t enough for her. And obviously we can’t ban it entirely—not just for one child.’

‘No, of course not,’ I tell her.

Her eyes are on me, her pale unreadable gaze.

‘And if anything it all seems to be getting worse now. Wouldn’t you say so?’

‘It certainly isn’t getting any better,’ I say, in a small voice.

‘I was wondering—have there been any changes in your circumstances? You know, anyone new on the scene?’

I think of Matt with a tug of regret.

‘Nothing like that,’ I tell her. ‘We have quite an uneventful life.’

She picks up her cup, takes a pensive sip.

‘And this house she draws over and over. The house with the blue border, and the doors and windows always just the same… We do encourage her to draw other things. Beth tried to get her to draw some people—you know, just very gently. “Can you draw a little girl for me?” But she wouldn’t. She’s a good little artist, I’ll grant her that, but I worry that there’s something rather obsessive about it…’

I remember girls at school who’d mastered horses or brides, who always did the same doodle in the margins of their books.

‘I think she was just so pleased she’d learned to draw houses,’ I say.

She ignores this. She leans towards me across the desk, her fingertips steepled together.

‘Ms Reynolds.’ Her voice is low, intimate. ‘I hope you don’t mind me raising this, but you’re quite sure that this isn’t a place where something happened to her?’

There are patches of burgundy in her cheeks. I hate this. I know she’s asking if Sylvie might have been abused.

‘I’m absolutely sure,’ I tell her.

‘You see, it can be a way that children cope with trauma—this kind of obsession. Reliving the trauma over and over, trying to make sense of it. Beth did try to find out—she asked her who lived in the house. But Sylvie wouldn’t say.’

‘Maybe she doesn’t think about who lives there.’

‘Well, maybe not,’ says Mrs Pace-Barden, not persuaded. ‘Let’s hope I’m wrong. I can see that this is all rather painful for you. But for Sylvie’s sake these things have got to be addressed.’

‘If there was anything, I would know,’ I tell her. ‘She’s always with me, or here at nursery, or playing with Lennie, her friend. There’s nothing I don’t know about.’

‘As parents, we like to think that,’ she says. ‘We think we know all there is to know about our children. I understand that—I’ve got children of my own. But sometimes we can delude ourselves. Sometimes we don’t know everything…’

She takes the coffee pot, refills my cup although it’s still half full. It’s a moment of punctuation. I feel a flicker of hopefulness: that she will come up with some help for Sylvie, some kind of programme or plan.

I see her throat move as she swallows. She isn’t quite looking at me.

‘I hope you don’t mind me raising these things. But we need to get this sorted. Because, to be frank, Ms Reynolds—unless the situation improves, I’m really not sure that we can keep your daughter here.’

I put my cup down. Slowly, concentrating hard, so the coffee won’t slop in the saucer. Suddenly everything has to be done with such elaborate care.

‘I’m sorry,’ she says. ‘I can see this is a shock for you. But the truth is we just don’t have the resources to cope with a child with problems on this scale. She’s a one-to-one a lot of the time and that’s not what we’re about here—not with the three-and four-year-olds. It’s intended to be a pre-school class—they’re learning independence. We really can’t cater for children as needy as Sylvie seems to be…’

I fix my gaze on the garden through her window. Everything seems to recede from me—the fretted shadows across the bright grass, the wet black branches of trees—and the children’s voices sound hollow, remote, like voices heard over water.

‘But surely there must be someone who could help us?’ I hear how shrill my voice is.

‘Well,’ she says slowly, ‘there is a child psychiatrist I know. We’ve used him before, with children here. Dr Strickland. He works at the Arbours Clinic. It’s possible he could take Sylvie on for some play therapy.’

‘All right. We’ll see him,’ I say.

‘Good,’ she says. Her smile is switched back on again, her hockey-mistress buoyancy restored. ‘I think that’s an excellent decision. I’ll write to him, then,’ she tells me.

Outside, there’s the drip and seep of the thaw, and the sky is blue and luminous. I walk rapidly along the road, through the moist, chill air and the dazzling yellow sunlight. I feel fragile—cardboard-cutout thin, my vision blurred with tears.

CHAPTER 8

I hunt around in my kitchen. I’m out of chicken nuggets, which are Sylvie’s favourite dinner, but there’s cheese, and plenty of vegetables. Tonight I will make something different and healthy, a vegetarian crumble. I fry tomatoes and onions, stir in chickpeas, make a crunchy topping of breadcrumbs and grated cheese.

Sylvie is in the living room, playing with her Noah’s Ark. She has lots of plastic animals, and she’s putting them in long straight lines, so they radiate out from the ark like the beams from a picture-book sun. She sings a whispery, shapeless song. She’s wearing her favourite dungarees that have a pattern of daisies. When she bends low over her animals, her silk hair swings over her face.

While the crumble cooks, I clean and tidy everywhere, so the flat is gleaming and orderly. There’s a rich smell from the oven, a luxurious scent of tomatoes and herbs, like a Mediterranean bistro. My jaw still aches, with a blunt, heavy pain: perhaps this is something more serious than neuralgia. I work out the date of my last dental check-up. Four years ago, when I was pregnant, when you get treated free.

I bring the crumble to the table, serve up Sylvie’s portion.

‘We’re having something a little bit different today,’ I tell her.

I start to eat. I’m pleased. It tastes good.

Sylvie moves a chickpea around on her plate with her fork.

‘I don’t like it,’ she says.

‘Just try it, please, sweetheart. It’s all there is to eat today. We’re out of chicken nuggets.’

‘I don’t want it,’ she says. ‘It’s yucky. It tastes of turnips.’

‘You don’t know that. You can’t know what it tastes of. You haven’t even tried it. Anyway, when have you had turnips to eat exactly?’

‘I do know, Grace.’ She pokes a chickpea with her fork and raises it to her face and smells it with a noisy, melodramatic sniff. ‘Turnips,’ she says.

I hear Karen’s voice in my head, brisk and assured and sensible, knowing just what she’d say. You can’t let her have her own way, just because she doesn’t like vegetables. Children need boundaries, Grace. You can’t always let her get away with everything. She’ll run rings around you…

‘Sylvie, look, I want you to eat it. Just some of it, just a bit. If you don’t at least try it, there won’t be any pudding.’

She puts her fork on the table, precisely aligned with her plate, with a sharp little sound like the breaking of a bone.

‘I don’t want it.’ Her face is hard, set.

‘Sylvie, just eat it, OK?’

My chest tightens. I feel something edging nearer, feel its cool breath on my skin. But I try to tell myself this is just an everyday argument—a child refusing to eat, a parent getting annoyed. I tell myself this is nothing.

Her eyes are on me. Her gaze is narrow, constricted, the pinpricks of her pupils like the tiniest black beads. She looks at me as though she doesn’t recognise me, or doesn’t like what she sees.

‘I don’t like it here,’ she tells me. Her voice is small and clear. ‘I don’t like it here with you, Grace.’

The look in her eyes chills me.

I don’t say anything. I don’t know what to say.

‘I don’t like it here,’ she says again.

I stare at her, sitting there at our table in her daisy dungarees, with her wispy pale hair, her heart-shaped face, this coldness in her gaze.

Rage grabs me by the throat. I want to shake her, to slap her, anything to make that cold look go away.

She pushes the plate to the other side of the table, moving it carefully, not in a rush of anger, but very controlled and deliberate. She turns her back to me.

‘Stop it. Just stop it.’ I’m shouting at her. I can’t help myself. My voice is too loud for the room, loud enough to shatter something. ‘Jesus, Sylvie. I’ve had enough. Just stop it, for God’s sake, will you?’

She sits quite still at the table, with her back to me. She presses her hands to her ears.

If I stay, I’ll hit her.

I go to the bathroom, slam and lock the door. I sit on the edge of the bath, rigid, my fists clenched, my nails driving into my palms. I can feel the pounding of every pulse in my body. I sit there for a long time, making myself take great big breaths, sucking the air deep into my lungs like somebody pulled from the sea. Gradually, my heart slows and the anger seeps away.

I’m aware of the pain again. It’s worse now, drilling into my jaw. I find two Nurofen at the back of the bathroom cabinet. But my throat is tight, they’re hard to swallow, I’ve sucked off all the coating before I get them down. They leave a bitter taste.

In the living room, Sylvie is on the floor again, busy with her Noah’s Ark, humming softly to herself, as though none of this had happened.

‘I’ll make you some toast,’ I tell her.

She doesn’t look up.

‘With Marmite?’ she says.

‘Of course. If that’s what you’d like.’

I make her the toast, put milk in her cup. I eat a few mouthfuls of crumble, though my appetite has gone. I clear the table.

‘Shall we watch television?’

She nods. We sit together on the sofa, and she curls in close to me, taking neat bites of her toast. If she drops a crumb she licks her finger and dabs at the crumb and sucks it from her fingertip. It’s a wildlife programme, about otters in a stream in the Scottish Highlands. She loves the otters, laughs at their quick, lithe bodies, the way they slide across the rocks as sleek and easy as water. As we sit there close together, it feels happy again between us, the bad scene just a memory, faint as the slight bitter taste in my mouth.

‘Sweetheart, I’m sorry I shouted at you,’ I tell her. ‘I don’t feel well. My tooth hurts.’

She’s nestled in the crook of my arm. She looks up at me.

‘Which one, Grace?’ she says.

‘It’s here.’ I point to the sore place. ‘I’ll have to go to the dentist—he’ll probably take it out.’

She reaches across and rests her hand against the side of my face.

‘There,’ she says.

The tenderness in the gesture melts me. I hug her to me, bury my face in her hair, in her smell of lemons and warm wool. She lets herself be held.

CHAPTER 9

The receptionist greets me: she’s married to one of the dentists who work here. She has a faded prettiness and bleached, dishevelled hair.

‘Toothache?’ she says.

‘I’m afraid so.’

‘Oh, dear.’ She shakes her head, a little disapproving. ‘You shouldn’t have left it so long.’

The waiting room has a fish tank and comfortable chairs. I sit and watch the fish. They have a transparent, unnatural look, like embryos, and their slow, threaded dance is hypnotic. There’s the faintest antiseptic smell, like that green astringent liquid the dentist gives you to rinse with. It’s very warm, and quiet with double glazing at the windows, so all you hear is the softest hum of traffic from the street. It’s pleasant sitting doing nothing, the warmth easing into my limbs.

There are papers and magazines on the table beside me. I look casually through the magazines, hoping for something glamorous, for opulent taffeta frocks and fetishy shoes; but they’re all just property journals.

A woman comes in and speaks to the receptionist. She’s dressed discreetly, in business black with sensible court shoes, but I can’t help staring at her: her face is a mess, the skin around one eye all bruised and broken. Someone must have attacked her; perhaps she lives with a violent man. She sits beside the fish tank, very straight and still, as though moving too much could hurt her.

The dentist’s wife puts down her pen.