The Emperor Waltz

‘That’s not ironic, my dear,’ Alan said. ‘That’s just Duncan running out of money for the telephone. Don’t sit over there all on your own. Come and sit down by me. I want to hear all about it.’

‘So I wasn’t going to come, but now I have come, though I can’t stay, because I’ve got to go on to tell everyone I can find in Earls Court, but you’ve all got to come to the Embassy later. Duncan’s back!’ Paul said, waving his hands like Al Jolson, taking the vodka and tonic and downing it in one, then getting up and, instead of going over to Alan, trotting off down the stairs. For some reason, Nat and Alan got up and went to the window; they watched him walk down the street in his shorts, with his bag over the crook of the arm. Outside the window hung two small Union Jacks; they had been there since the Silver Jubilee, two years before, and the landlord saw no reason to remove them. The sensibilities of his radical customers, who rented the upstairs room once a week or once a fortnight, did not worry him.

‘I don’t think,’ Christopher said, ‘I ever met Paul’s friend Duncan.’

So then they all told him about Duncan.

9.

‘Who is that coming up the path?’ Aunt Rachel said, peering out of the window.

‘It’s some man,’ Aunt Rebecca said. ‘He is probably selling something from his little bag. Silk stockings and shoe brushes. How dark he is!’

‘I know who it is,’ Aunt Ruth said with a note of triumph. ‘He is that horrid little boy.’

Duncan had been delayed: the plane to Paris had been an hour late, and he had just missed his connection; the next plane from Paris had been four hours later; his luggage had been lost or mislaid in the confusion, and he had had to fill in a lot of forms at Heathrow. All his clothes were somewhere between Catania and London – they could be anywhere in Europe. The only clothes he had were in a suitcase somewhere under his sister’s bed in Clapham, and the ones in his hand luggage, the tiny shorts and T-shirt he had changed out of at the airport. He had meant to get to his father’s house before lunchtime, but it was now nearly night. He was ravenous.

All the way up the hill, he had been thinking of food – he wanted solid, dry English cheese and perhaps, if there was some leftover cold mashed potato in a bowl, that fried with some peas. Sicilian potatoes didn’t go into any kind of mash – too waxy, or something. Even the sight of his father’s ramshackle house hadn’t shifted his thoughts. But when he rang the doorbell, and it had its familiar, inexplicable half-second delay before sounding, its four-note Big Ben call, which had been there for twenty years at least, Duncan remembered where he was and how much of his life had been there. The house bell was so jaunty, and so little of the life within was jaunty. The sound of the doorbell could always bring him and Dommie to their feet, racing downstairs to open it to whoever it was – usually the postman or the meter reader, nothing more exciting than that. It was the things you put out of your mind that could come back into it, with force.

Aunt Rebecca opened the door. She had put on some weight since he had last seen her, seven years ago at Christmas. She was pretending not to know who he was, but overdoing it in an amateurish way. She peered into his face, screwing up her eyebrows and forehead. ‘Yes?’ she said, hooting rather. ‘Can I help you?’

Duncan wished he had insisted when he left home that he had kept a key. But his father had said he couldn’t have sets of keys being mislaid all over London, and he’d always be there to let Duncan in – or if he weren’t, then he didn’t want Duncan going all over the house in his absence. Dommie had done better and insisted; Duncan had been weak and now, with his father dying upstairs, was at the mercy of his aunt.

‘It’s me,’ he said. ‘Duncan. How are you, Rebecca?’

‘Aunt Rebecca, you used to call me,’ she said. ‘How extraordinary. I thought you were in Italy.’

‘I was in Italy,’ Duncan said. ‘But I had a telegram saying that my dad wasn’t very well.’

‘Ha!’ Rebecca said. ‘That is an understatement. He’s very ill indeed.’

‘So I came,’ Duncan said. ‘I came as fast as I could. Can I come in?’

Rebecca had been leaning with her arm heavily against the doorjamb, guarding; the word ‘dragon’ came into Duncan’s mind. It was her weight and awkwardness; but she was blocking Duncan’s way all the same. She gave him a thorough look. ‘Of course,’ she said. ‘I don’t know whether your father can see you. He has been very uncomfortable the last two days.’ Duncan felt accused by her expression, as if he had been the cause of the discomfort, even though he had not even been in the country. ‘He is only sleeping in fits and starts, so I won’t wake him if he’s asleep. You could come back tomorrow.’

‘He might be asleep when I come tomorrow,’ Duncan said, putting his little bag down in the hall by the hatstand. All the doors in the hall were closed, as if in the central lobby of some office. They had never been closed like that before; doors had stood open or closed as they happened to be. In the panelled hallway, closed off, with nothing but the wooden stair rising upwards to the death chamber, Duncan found himself in an unfamiliar and formal house. ‘I’ll wait until he wakes up.’

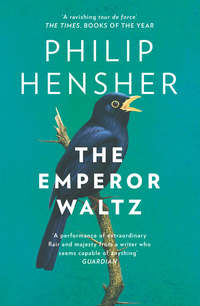

‘Oh, very well,’ Rebecca said. She retreated into the sitting room; she opened the door and there was the sight of a woman reading in the gloom. The lights had not been switched on; there was only a small table lamp by the side of her, and she peered in a pool of light downwards, not looking up as Rebecca entered. It was either Ruth or Rachel; he could not see. They must have heard him coming in, perhaps even discussed who should answer the door. There was something territorial about her, something relaxed and confident about her ownership. She was saving her own electricity bill, not her brother’s, by reading in the dark; she was not greeting him because he was there to perform a function, like a meter reader or a Gas Board employee. She might as well have been counting the silver spoons. And now, as if from nowhere, a shape leapt onto the back of her chair; not a cat, but an animal of burst and flutter. It took a strut into the small pool of light, and Duncan saw that it was a parrot, quite black. The parrot tipped its head on one side; it looked in Duncan’s direction; it raised a foot and began to groom itself, quite uninterested in the new arrival. Presently the aunt reached up behind her. She had taken something – a nut or a seed – from her lap, and the bird snatched it. All this Duncan watched remotely, as if it were a drama on a television screen. And then an unknown force seemed to push the door behind Rebecca, and it closed, leaving him alone with the staircase.

The stairs creaked. He felt like a burglar. And upstairs the bedroom doors were also closed. For the first time, Duncan saw the box-like construction of the hall downstairs, the landing upstairs; the distinguished shape that the house had once had, and still had at its core. The panelling continued upstairs, and a threadbare green and blue carpet. This was where Samuel had hung his less successful acquisitions in the way of paintings, including the ‘Constable’, signed extravagantly, from which he had hoped to make a fortune until he was laughed out of Sotheby’s – a red-jacketed farm boy on a wagon in the middle of a dark wood. Samuel’s bedroom was in the middle. Duncan gave a very gentle knock, and in a moment there was a small crisp bustle and the door was opened by what must be a nurse. She came out, closing the door softly behind her.

‘Are you Duncan?’ she said. ‘I’m Sister Balls. We’ve been having a slightly restless couple of days, and sometimes he doesn’t make the best sense, but I don’t think he’s in pain any more. He’s falling asleep and waking up and falling asleep again, but he’ll be very happy to see you.’

‘I don’t think so,’ Duncan said. ‘It’s kind of you to say so, though.’

‘Now why would you say that?’ Sister Balls said. ‘He’s asleep, but he’s been asking after you a lot, saying, When is he going to get here? I’ll be all right when Duncan gets here. It’s been very nice to listen to and to be able to say that you were definitely coming today.’

‘Shall I wait downstairs?’ Duncan said.

‘Oh, no,’ the nurse said. ‘No, that’s not necessary. Just come in quietly and hold his hand, and he’ll wake up when he’s ready, and then I’ll go and leave you two in peace for a bit. Don’t tire him out, I’m sure you won’t.’

Duncan felt a kind of gratitude to Aunt Rebecca for being so abrupt, to the other two aunts for being so rude as not to come out to greet him. He felt tenderized. Talking to Sister Balls, he had been admitted to a caring space, concealed and protected. Then the nurse opened the door to the dark room, and he remembered that inside that space, his father lay.

There was the smell of an enclosed hot room, and something alongside, unexpected. Oh, he thought, that’s the smell of a deathbed. But it wasn’t unpleasant, or particularly human, apart from its warmth; it smelt of something unfamiliar, something welcome, and some blocking agents on top, floral and medical and antiseptic. His father’s room had its own smell, too, a masculine one of wood and shoe polish. Duncan went in, closing the door behind him softly. The room was very dim. But he didn’t want to turn the light on and startle his father. He groped around the room, to the side of his father’s head, and in a moment he banged against the winged armchair that had always been on the landing until now, in case anyone tired themselves out climbing the stairs. He felt on the seat to make sure there was no medical equipment – he had a dread of syringes and containers, of cardboard bedpans – and sat down cautiously. He could hear his father’s breathing. Not dead yet. He sat for a few minutes, and shortly his eyes got used to the dim light, as his nose got used to the room’s lingering odours of illness and cure. His father’s profile was sharp and drawn; his hands were under the counterpane, making a pulling gesture. Duncan waited. There might be no need to remain. He had seen his father now. He would wait only fifteen minutes more. But just then, his father gave a deep, rasping breath, as if choking, and woke. His eyes were still closed, but there was a change in his being and his breathing. He gave the impression of being disappointed to wake and find himself still alive.

‘Who’s there,’ his father said. ‘I can’t see.’

‘It’s me,’ Duncan said. Then there was a pause, a lingering silent question, and Duncan had to say, ‘It’s Duncan, Daddy.’

‘Oh, Duncan,’ his father said. ‘I thought you were in Italy. Well, better late than never.’

‘I came as fast as I could,’ Duncan said. ‘I only heard two days ago, and the earliest flight I could get was last night and today. I had to change in Paris – there was no direct flight.’

‘Heard what,’ his father said. ‘That’s what I’d like to know.’

‘Just heard,’ Duncan said. ‘I came over as quickly as I could.’

‘Always in a great rush,’ his father said. ‘Always not doing things properly because of something that’s turned up in an emergency. You were the same as a little boy.’

‘Oh, I don’t know,’ Duncan said, finding himself unable to think of what he should have done to preserve his father’s sense of the right thing to do, while simultaneously coming as soon as possible. ‘I do my best.’

‘Have you seen your sister?’ Samuel said. ‘I was expecting to see her, as well.’

‘Are you sure she hasn’t been?’ Duncan said. ‘I’m sure she’s been to see you. Hasn’t she?’

‘What do you think I am?’ his father said. His voice was dry and rasping; the heat in his throat, its pain, tangible. His eyes were still closed; the annoyance of his existence, his ways as if a headmaster, surviving until his last moments. Duncan reflected that anyone else, he would pass him a glass of water without a request. His father would demand one, and then expect the person to put up with being called an idiot for not having one poured out ready. He waited. ‘Do you think I can’t remember if Domenica has been or not? I’m ill, not stupid.’

‘Sometimes you’re not quite sure of things when you’re as ill as this,’ Duncan said.

‘She hasn’t been,’ Samuel said. ‘I don’t suppose it’s important to her.’

And then, to Duncan’s horror, his father raised his hands to his face in a gesture of self-benediction, his palms over his eyes, and began to sob, juddering. ‘My life’s been for nothing,’ his father said. ‘My life, and my children can’t wait for me to die.’

‘You don’t need to think that,’ Duncan said. ‘Don’t say things like that.’

His father’s noise of weeping would soon bring the nurse into the room or, worse, his sisters. But then downstairs a harsh call came; a barbaric yawp and shriek. It seemed to interest or divert his father, and, just as a child’s tantrum can be pushed to one side by an entertainment, so his father paused in his fit, just gave one more shudder, and lowered his hands. ‘I keep hearing that noise,’ he said. ‘I don’t know what it is. It’s like an animal crying.’

‘It’s a parrot,’ Duncan said. ‘It’s a black parrot that Ruth brought. Or Rachel. I don’t know which one.’

‘It would be Rachel,’ Samuel said. ‘She has a parrot, a black one. Why has she brought it here? I don’t want it here. I don’t want that noise downstairs.’

‘I don’t know,’ Duncan said. ‘I thought she must have asked you. I’ll tell her to take it home again.’

‘Oh, she won’t do that,’ Samuel said. Then all at once he fell asleep; so instantly that Duncan thought it must be a coma or even a final collapse. He went about the room moving things, putting off the moment when he must go outside and say that his father seemed to have taken a turn for the worse. In curiosity rather than anything else, he turned on the bedside lamp. It was the same pink fringed one his mother had always had. The light showed an old, unshaven man, the cheeks sunk in deep under the cheekbones and the eye sockets like a skull’s, falling profoundly into worlds of darkness. The skin was yellow and slack, as if its possessor had slept long under bridges, living on methylated spirits. Only the cleanliness of the dark blue pyjamas with white piping, and the neatness of the sheets, suggested anything but the derelict. It was as if an old tramp had been taken from his streetside cardboard box by a benevolent, given a bath and set down within clean linen to die. Duncan resisted the temptation to run his hand down the side of his father’s face. There was no temptation to kiss it. But the thought came to mind like this: what would it be like to have a father who, on his deathbed, you wanted to kiss? The light had disturbed Samuel in his sudden sleep, and now he woke, raising his fists to his eyes and rubbing them, yawning like a cat, turning about to see what the disturbance was.

‘Oh, it’s you again,’ Samuel said. ‘I didn’t know if it was really you. I keep thinking people are here. You should have stayed in Spain. No, in Italy, that’s where you’ve been.’

‘I’ve come back,’ Duncan said. ‘I’m not going to tire you out. I’ll come back tomorrow.’

‘Yes, perhaps that’s best,’ Samuel said.

(And downstairs Rachel was turning to her sisters and saying what she should have said hours, or days ago; saying that she had, in fact, not got round to taking anything to the solicitor’s, that she was rather afraid that the will was upstairs still, in poor Samuel’s keeping. ‘But he won’t know about that, the son, will he?’ she was saying plaintively, and Ruth was shaking her head, and Rebecca was shaking her head, too.)

Samuel looked around conspiratorially. ‘I’ll tell you something important tomorrow, if you come back.’

‘You can tell me now, if you like,’ Duncan said. ‘I don’t mind listening.’

‘It’s not a question of whether you want to listen or not,’ Samuel said. ‘It’s whether I want to tell you. It’s my business.’

‘Well, you can tell me or not tell me,’ Duncan said. ‘But if I were you, I wouldn’t put anything much off until tomorrow that you want people to know.’

‘You wouldn’t, wouldn’t you?’ Samuel said. But doubt set in, and he started saying ‘You wouldn’t, would you – would, would, wouldn’t, should,’ until he could no longer decide what it was normal to say, and he fell silent.

‘You know,’ Duncan said, quite calmly, ‘it’s very bad luck, getting lung cancer like that. Not smoking, ever, and then you get lung cancer. I don’t know that that’s supposed to happen.’

‘I did smoke,’ Samuel said. ‘But before you were born. Before I met your mother, even. It was when I was at school, and when I had my first job. I was a clerk in the office of – of – of – they were Jews. That’s right, they were Jews, the first people I worked for. I smoked because they didn’t, none of them. But it didn’t do me any good. I gave up just before I met your mother and before I went to another job. That was when I realized that I was never going to be promoted in that place. They only promoted their own type.’

‘That must have been fifty years ago,’ Duncan said. He wondered that he did not know that his father had ever smoked. His mother, he was sure, never had. ‘I don’t think you get lung cancer from that, decades later.’

‘They don’t know,’ Samuel said. ‘Doctors never know. I’m glad I’m not in hospital. I’m glad they’re letting me stay here.’

‘Do you remember,’ Duncan said, and Samuel, for the first time, turned his head towards him, and almost smiled. ‘Do you remember that day when you and Mummy and Dommie and I, we went out for the day? I think it must have been for Dommie’s birthday.’

‘I think so,’ Samuel said. His lips were dry and flaking; he was running his tongue over them.

‘Where did we go? Did we go to Whipsnade, or some other zoo, or Box Hill, or was it to the theatre? It would have been a special treat. I don’t know that Whipsnade was open then, come to think of it, so maybe not there. And did you ask Dommie if she’d like to bring ten friends with her? I wish I could remember what her special treat was.’

Samuel turned his head away. ‘When it gets worse,’ he said, ‘they’ll take me into hospital, but I hope I’m not going to know about any of that.’

‘Oh, you’re not going to get any worse than this,’ Duncan said lightly. ‘This is probably it. I wouldn’t have thought you had long to go. About Dommie’s birthday. What was it that we all did together? I think I remember now. She was going to be nine, and you told her that you thought she was too old to have a party, and she couldn’t ask her friends round because it would cost too much and it would be too much noise and trouble. But since you ask, you’re not going to get any worse. You’re probably going to die quite soon.’

Samuel turned his face to Duncan in disbelief. His hollows and unshaven angles said only this: it’s your obligation to do whatever I say. It was not for Duncan to do anything but to give way.

‘So,’ Duncan said. ‘Are you comfortable? Can I do anything for you, in your last hours? Or do you just want me to go away so that you can sit with Rebecca and Ruth and Rachel? I don’t really care.’

‘Oh, you think you’re so clever,’ Samuel said, breathing deeply, the air juddering within. He raised his thin hand to his hairy, bony chest in the gap in his pyjama jacket. ‘That’s what you were always like, showing off. Let me do my dance – I made it up, Mummy. Look, Aunty Rachel, look, Uncle Harold, look at the dolly I made, isn’t it pretty. Oh, yes. I can see you came back to show off and tell me to bugger off before I die. But I can show you one thing.’

There was a long pause; Samuel’s breath guttered and shuddered; he twisted in pain; he pulled at the bedsheets. Duncan waited. He did not want to help his father. He wanted to see how long it would take him to return to the point where he could speak again, or sleep. He watched with interest. In less than five minutes, his father had calmed. Outside the door, a chair scraped against the parquet. Sister Balls must have returned, and be sitting outside. He did not have a lot of time.

‘It hurts to talk,’ Samuel said. ‘There’s one thing I want you to see. In that box, there, on the dressing-table.’

Duncan went over and drew it out. It was a document; a pre-printed form filled in in Samuel’s wavering looping hand, a will. ‘I don’t want to see this,’ Duncan said.

‘Look at it,’ Samuel said.

Duncan did. There was what looked like a duplicate underneath. In a moment he read that his father was leaving his whole estate in equal parts to his two children, his three sisters, his five nephews and nieces, and seven named charities and educational institutions, including the Harrow rugby club, and Harrow School, which neither Duncan nor his father had attended. ‘I see,’ Duncan said. The will, which was to give him, what, a seventeenth part of this ugly house and the bank balance, was dated from two months ago. It was witnessed by a Corinna Balls, and another woman, whose handwriting made Duncan think she was another nurse.

‘You didn’t ask Aunt Rebecca or Aunt Ruth to witness it,’ he said.

‘No, you stupid boy,’ Samuel said. ‘You can’t get people to witness something they’re going to—’ He broke down in coughing.

‘Going to benefit from,’ Duncan said. ‘They’re not going to benefit very much, though, are they?’

‘I think,’ Samuel said. ‘I think – I’m going to cross Domenica out. She hasn’t been to see me. So you’ll get a little bit more. That’ll be nice, won’t it.’

‘And a lawyer’s drawn this up, has he?’ Duncan said. Samuel looked withdrawn and serene. ‘Oh, I see – it’s just something you’ve bought from the newsagent and filled in. Got Sister Balls to get from the newsagent. Something for everyone to discover after you die? I see. You just want people to know that they don’t deserve anything from you.’

Duncan looked at his father. He knew perfectly well that Duncan would take this document and destroy it. It could have no effect on what happened to Samuel’s estate. But before Samuel died, he wanted to make clear to Duncan what he thought of him.

‘The thing is,’ Duncan said, ‘I don’t think that Domenica would take your money anyway. I think she’d probably take however much it was, and hand it over to the NSPCC. Do you think she wants anything to do with you?’

‘I’m her father,’ Samuel said.

‘There was an afternoon, wasn’t there,’ Duncan said, ‘when you said, Let’s all go out swimming, the children and I. Which was odd, because you never suggested anything like that for the children’s pleasure. You know, don’t you, that because Dommie never had any parties after she was eight years old, no one ever thought to ask her to theirs? I don’t suppose you ever thought of that. You only ever wanted to do your own thing. And Dommie said that she couldn’t swim, she didn’t know how, and you said that didn’t matter. You’d gone to the effort of buying her a swimming costume. She didn’t have one. She was only six. And when we all got to the swimming pool, you said to her, This is the way to swim, you know, and you picked her up by her arms and legs and threw her into the deep end, with no floats or anything, and just stood there. The lifeguard jumped in and rescued her. He gave you what for, you horrible old man, asking you what you thought you were doing. Don’t you remember?’

Samuel shook his head demurely. He looked like such a small person, a small entrapped dwarf in a fairytale with a secret.

‘I remember. Even in the 1950s, you didn’t just throw small children into the deep end of swimming pools and wait to see if they drowned or not.’

‘Oh, once,’ Samuel said, shaking his head.

‘Every week,’ Duncan said. ‘Making her wait at the table to eat mutton fat. Making her walk all the way back to school in the dark in January to make her find a pencil case she had dropped. Do you know, you’ve never once given me any help or advice – you’ve never done anything for me, except once. Mummy made you explain to me how to shave. You couldn’t get out of that. That was it. I’m glad you’re dying. It won’t make the slightest difference to anyone. And what’s this rubbish?’ He held up the will. In the light it was a sad object: the handwritten parts were shaky and full of uneven gaps and holes. ‘No one’s going to pay any attention to that. I’m surprised Balls didn’t tell you not to be so stupid. Shall I burn it or shall I just tear it up?’