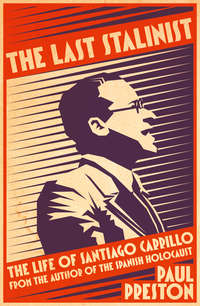

The Last Stalinist: The Life of Santiago Carrillo

Although political power had passed from the oligarchy to the moderate left, economic power (ownership of the banks, industry and the land) and social power (control of the press, the radio and much of the education system) were unchanged. Even if the coalition had not been hobbled by its less progressive members, this huge programme faced near-insuperable obstacles. The three Socialist ministers realized that the overthrow of capitalism was a distant dream and limited their aspirations to improving the living conditions of the southern landless labourers (braceros), the Asturian miners and other sections of the industrial working class. However, in a shrinking economy, bankers, industrialists and landowners saw any attempts at reform in the areas of property, religion or national unity as an aggressive challenge to the existing balance of social and economic power. Moreover, the Catholic Church and the army were equally determined to oppose change. Yet the Socialists felt that they had to meet the expectations of those who had rejoiced at what they thought would be a new world. They also had another enemy – the anarchist movement.

The leadership of the anarchist movement expected little or nothing from the Republic, seeing it as merely another bourgeois state system, little better than the monarchy. At best, their trade union wing wanted to pursue its bitter rivalry with the Union General de Trabajadores, which they saw as a scab union because of its collaboration with the Primo de Rivera regime. They thirsted for revenge for the dictatorship’s suppression of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo throughout the 1920s. The hard-line activist wing of the anarchist movement, the Federación Anarquista Ibérica, aspired to greater liberty with which to propagate its revolutionary objectives. The situation could not have been more explosive. Mass unemployment was swollen by the unskilled construction workers left without work by the collapse of the ambitious public works projects of the dictatorship. The brief honeymoon period came to an end when CNT–FAI demonstrations on 1 May were repressed violently by the forces of order. It was the trigger for an anarchist declaration of war against the Republic and the beginning of a wave of strikes and minor insurrections over the next two years.36

Needless to say, anarchist activities against the Republic were eagerly portrayed by the right-wing media, and from church pulpits, as proof that the new regime was itself a fount of godless anarchy.37 Despite these appalling difficulties, the Federación de Juventudes Socialistas shared the optimism of the Republican–Socialist coalition. When the Republic was proclaimed on 14 April, FJS militants had guarded buildings in Madrid associated with the right, including the royal palace. On 10 May, when churches were burned in response to monarchist agitation, the FJS also tried to protect them.38 However, as the obstacles to progress mounted, frustration soon set in within the Socialist movement as a whole.

The first priority of the Socialist Ministers of Labour, Francisco Largo Caballero, and of Justice, Fernando de los Ríos, was to ameliorate the appalling situation in rural Spain. Rural unemployment had soared thanks to a drought during the winter of 1930–1 and thousands of emigrants were forced to return to Spain as the world depression affected the richer economies. De los Ríos established legal obstacles to prevent big landlords raising rents and evicting smallholders. Largo Caballero introduced four dramatic measures to protect landless labourers. The first of these was the so-called ‘decree of municipal boundaries’ which made it illegal for outside labour to be hired while there were local unemployed workers in a given municipality. It neutralized the landowners’ most potent weapon, the import of cheap blackleg labour to break strikes and depress wages. He also introduced arbitration committees (jurados mixtos) with union representation to adjudicate rural wages and working conditions which had previously been decided at the whim of the owners. Resented even more bitterly by the landlords was the introduction of the eight-hour day. Hitherto, the braceros had worked from sun-up to sun-down. Now, in theory at least, the owners would either have to pay overtime or else employ more men to do the same work. A decree of obligatory cultivation prevented the owners sabotaging these measures by taking their land out of operation to impose a lock-out. Although these measures were difficult to implement and were often sidestepped, together with the preparations being set in train for a sweeping law of agrarian reform, they infuriated the landowners, who claimed that the Republic was destroying agriculture.

While the powerful press and radio networks of the right presented the Republic as the fount of mob violence, political instruments were being developed to block the progressive project of the newly elected coalition. First into action were the so-called ‘catastrophists’ whose objective was to provoke the outright destruction of the new regime by violence. The three principal catastrophist organizations were the monarchist supporters of Alfonso XIII who would be the General Staff and the paymasters of the extreme right; the ultra-reactionary Traditionalist Communion or Carlists (so called in honour of a nineteenth-century pretender to the throne); and lastly a number of minuscule openly fascist groups, which eventually united between 1933 and 1934 under the leadership of the dictator’s son, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as Falange Española. Within hours of the Republic being declared, the ‘Alfonsine’ monarchists had met to create a journal to propagate the legitimacy of a rising against the Republic particularly within the army and to establish a political party merely as a front for meetings, fund-raising and conspiracy against the Republic. The journal Acción Española would peddle the idea that the Republican–Socialist coalition was the puppet of a sinister alliance of Jews, Freemasons and leftists. In the course of one month, its founders had collected substantial funds for a military coup. Their first effort would take place on 10 August 1932 and its failure would lead to a determination to ensure that the next attempt would be better financed and entirely successful.39

In contrast, the other principal right-wing response to the Republic was to be legal obstruction of its objectives. Believing that forms of government, republican or monarchical, were ‘accidental’ as opposed to fundamental and that only the social content of a regime mattered, they were prepared to work within the Republic. The mastermind of these ‘accidentalists’ was Ángel Herrera, head of the Asociación Católica Nacional de Propagandistas (ACNP), an elite Jesuit-influenced organization of about 500 prominent and talented Catholic rightists with influence in the press, the judiciary and the professions. They controlled the most modern press network in Spain whose flagship daily was El Debate. A clever and dynamic member of the ACNP, the lawyer José María Gil Robles, began the process of creating of a mass right-wing party. Initially called Acción Popular, its few elected deputies used every possible device to block reform in the parliament or Cortes. A huge propaganda campaign succeeded in persuading the conservative Catholic smallholding farmers of northern and central Spain that the Republic was a rabble-rousing instrument of Soviet communism determined to steal their lands and submit their wives and daughters to an orgy of obligatory free love. With their votes thereby assured, by 1933 the legalist right would be able to wrest political power back from the left.40

The efforts of Gil Robles in the Cortes to block reform and provoke the Socialists was witnessed, on behalf of El Socialista, by Santiago Carrillo, who had been promoted from the town-hall beat to the arduous task of the verbatim recording of parliamentary debates. This could be done only by dint of frantic scribbling. The job did, however, bring him into contact with the passionate feminist Margarita Nelken, who wrote the parliamentary commentary for El Socialista. Herself a keen follower of Largo Caballero at this time, she would encourage Santiago in his process of radicalization and indeed in his path towards Soviet communism.41

In the first months of the Republic, Santiago won his spurs as an orator, speaking at several meetings of the FJS around the province of Madrid. This culminated at a meeting in the temple of the PSOE, the Casa del Pueblo. Opening a bill that included the party president, Julián Besteiro, he was at first tongue-tied. However, he recovered his nerve and made a speech whose confident delivery contrasted with his baby-faced appearance. In it, he betrayed signs of the radicalism that would soon distinguish members of the FJS from their older comrades. He declared that the Socialists should not be held back by their Republican allies and that, in a recent assembly, the FJS had resolved that Spain should dispense with its army. His rise within the FJS was meteoric. He would become deeply frustrated as he closely followed the fate of Largo Caballero’s decrees and even liaised with strikers in villages where the legislation was being flouted. At the FJS’s Fourth Congress, held in February 1932 when he had just turned seventeen, he was elected minutes secretary of its largely Besteirista executive committee. This was rather puzzling since his adherence to the view of Largo Caballero about the importance of Socialist participation in government set him in opposition to the president of the FJS, José Castro, and its secretary general, Mariano Rojo.

Carrillo’s election was probably the result of two things – the fact that he was able to reflect the frustrations of many rank-and-file members and, of course, the known fact of his father’s links to Largo Caballero. Not long afterwards, he became editor of the FJS weekly newspaper, Renovación, which had considerable autonomy from the executive committee. From its pages he promoted an ever more radical line with a number of like-minded collaborators. The most senior were Carlos Hernández Zancajo, one of the leaders of the transport union, and Amaro del Rosal, president of the bankworkers’ union. Among the young ones was a group – Manuel Tagüeña, José Cazorla Maure, José Laín Entralgo, Segundo Serrano Poncela (his closest comrade at this time) and Federico Melchor (later a lifelong friend and collaborator) – all of whom would attain prominence in the Communist Party during the Civil War. Greatly influenced by their superficial and rather romantic understanding of the Russian revolution, they argued strongly for the PSOE to take more power. Their principal targets were Besteiro and his followers, who still advocated that the Socialists abstain from government and leave the bourgeoisie to make its democratic revolution.42

Carrillo’s intensifying, and at this stage foolhardy, radicalism saw him risk his life during General Sanjurjo’s attempted military coup of 10 August 1932. When the news reached Madrid that there was a rising in Seville, Carrillo – according to his memoirs – abandoned his position as the chronicler of the Cortes debates and joined a busload of Republican officers who had decided to go and combat the rebels. In this account of this youthful recklessness, he says that he left his duties spontaneously without seeking permission from the editor. However, El Socialista published a more plausible and less heroic version at the time. The paper reported that he had been sent to Seville as its correspondent and had actually gone there on the train carrying troops sent officially to repress the rising. Whatever the truth of his mission and its method of transport, by the time he reached Seville Sanjurjo and his fellow conspirators had already given up and fled to Portugal. The fact that Carrillo stayed on in Seville collecting material for four articles on the rising that were published in El Socialista suggests that he was there with his editor’s blessing.43

A close reading of the lucid prose that characterized the articles suggests that the visit to Seville was an important turning point in the process of his radicalization. In the first, he recounted the involvement of an alarming number of the officers in the Seville garrison. In the second, he described the indecision, not to say collusion, of the Republican Civil Governor, Eduardo Valera Valverde. He went on to comment on the role of the local aristocracy in the failed coup. In the third, after some sarcastic comments on the inactivity of the police, he praised the workers of the city. As far as he was concerned, the coup had been defeated because the Communist and anarchist workers who dominated the labour movement in the city had unanimously joined in the general strike called by the minority UGT. In the fourth, he reiterated his conviction that it was the workers who had saved the day, whether they were the strikers in the provincial capital or the landless labourers from surrounding villages who had readied themselves to intercept any column of rebel troops that Sanjurjo might have sent against Madrid.44

The entire experience consolidated Carrillo’s growing conviction that the gradualism of the Republic, particularly as personified by its ineffectual provincial governors, could never overcome the entrenched social and economic power of the right. His belief that what was needed was an outright social revolution was shared by an increasing number of his comrades in the Socialist Youth but not by its executive committee. Around this time, he undertook a propaganda tour of the provinces of Albacete and Alicante. He later believed that the itinerary chosen for him by the Besteirista executive was a dirty trick designed to cause him considerable discomfort. While some of the villages selected were Socialist-dominated, most were controlled by the CNT. In Elda and Novelda, heavily armed anarchists prevented his meetings going ahead. In Alcoy, he started but the meeting was disrupted and he had to flee by hitchhiking to Alicante. Such experiences were part of the toughening up of a militant.45

Yet another stage in the process took place when he was imprisoned after falling foul of the Law for the Defence of the Republic. Ironically, his mentor Largo Caballero had enthusiastically supported the introduction of the law on 22 October 1931 because he perceived it as directed against the CNT. Its application saw Carrillo and Serrano Poncela arrested in January 1933, and then tried for subversion because of inflammatory articles published in Renovación during the state of emergency that had been decreed in response to an anarchist insurrection. This was the uprising in the course of which there took place the notorious massacre of Casas Viejas in Cádiz. While Carrillo and Serrano Poncela were in the Cárcel Modelo in Madrid, anarchist prisoners were brought in. They aggressively rebuffed the attempts at communication made by the two young Socialists. Carrillo later regarded that first short stay in prison as a kind of baptism for a nascent revolutionary.46

Carrillo might have been in the vanguard of radicalism, but he was not alone. Given that the purpose of his reforms had been humanitarian rather than revolutionary, Largo Caballero was profoundly embittered by the ferocity and efficacy of right-wing obstacles to the implementation of his measures. The hatred of capitalism so powerful in his youth was reignited. Largo Caballero’s closest theoretical adviser was Luis Araquistáin, who, as his under-secretary at the Ministry of Labour, had shared his frustration at rightist obstruction. Greatly influenced by Araquistáin, Largo Caballero began to doubt the efficacy of democratic reformism in a period in which economic depression rendered capitalism inflexible. It was inevitably those Socialist leaders who were nearest to the problems of the workers – Largo Caballero himself, Carlos de Baraibar, his Director General of Labour, and Araquistáin – who were eventually to reject reformism as worse than useless. Writing in 1935, Araquistáin commented on the Socialist error of thinking that, just because a law was entered on the statute book, it would be obeyed. He recalled, ‘I used to see Largo Caballero in the Ministry of Labour feverishly working day and night in the preparation of far-reaching social laws to dismantle the traditional clientalist networks [caciquismo].’ It was useless. While the Minister drafted these new laws, Araquistáin had to deal with ‘delegations of workers who came from the rural areas of Castille, Andalusia, Extremadura to report that existing laws were being flouted, that the bosses [caciques] still ruled and the authorities did nothing to stop them.’ The consequent fury and frustration inevitably fed into a belief that the Socialists needed more power.47

By the autumn of 1932, verbally at least, Largo Caballero was apparently catching up with the radicalism of his young disciple. The scale of his rhetorical radicalization was revealed by his struggle against the moderate wing of the Socialist movement led by Julián Besteiro. At the Thirteenth Congress of the PSOE, which opened on 6 October, Besteiro’s abstentionist positions were defeated by the combined efforts of Prieto and Largo Caballero, and Largo Caballero was elected party president.48 In fact, the Thirteenth PSOE Congress represented the last major Socialist vote of confidence in the efficacy of governmental collaboration. It closed on 13 October. The following day, the Seventeenth Congress of the UGT began. It would be dominated by the block votes of those unions whose bureaucracy was in the hands of Besteiro’s followers, the printers (Andrés Saborit), the railway workers (Trifón Gómez) and the landworkers’ Federación Nacional de Trabajadores de la Tierra (Lucio Martínez Gil). Accordingly, and despite the growing militancy of the rank and file of those unions, the Seventeenth Congress elected an executive committee with Besteiro as president, and all his senior followers in key positions. Largo Caballero was in fact elected secretary general, but he immediately sent a letter of resignation on the grounds that the congress’s vindication of the role of Besteiro and Muiño in the December 1930 strike constituted a criticism of his own stance. He was convinced that the mood of the rank and file demanded a more determined policy.49

Largo Caballero’s position was influenced by events abroad as well as by those within Spain. He and indeed many others in the party, the union and particularly the youth movement were convinced that the Republic was seriously threatened by fascism. Aware of the failure of German and Italian Socialists to oppose fascism in time, they advocated a seizing of the initiative. Throughout the first half of 1933 the Socialist press had fully registered both its interest in events in Germany and its belief that Gil Robles and his followers intended to follow in the footsteps of Hitler and Mussolini. Largo Caballero received frequent letters from Araquistáin, now Spanish Ambassador in Berlin, describing with horror the rise of Nazism.50

In the summer of 1933, Largo Caballero and his advisers came to believe that the Republican–Socialist coalition was impotent to resist the united assault by both industrial and agricultural employers on their social legislation. In consequence, Largo Caballero set about trying to regain his close contact with the rank and file, which had faded somewhat during his tenure of a ministry. The first public revelation of his newly acquired radical views began with a speech, in the Cine Pardiñas in Madrid on 23 July, as part of a fund-raising event for Renovación. In fact, the first part of the speech was essentially moderate and primarily concerned with defending ministerial collaboration against the criticisms of Besteiro. However, a hardening of attitude was apparent as he spoke of the increasing aggression of the right. Declaring that fascism was the bourgeoisie’s last resort at a time of capitalist crisis, he accepted that the PSOE and the UGT had a duty to prevent the establishment of fascism in Spain. Forgetting that, in the wake of the defeat in 1917, he had resolved never to risk conflict with the apparatus of the state, he now announced that if the defeat of fascism meant seizing power and establishing the dictatorship of the proletariat, then the Socialists, albeit reluctantly, should be prepared to do so. Enthusiastic cheers greeted the more extremist portions of his speech, which confirmed his belief in the validity of his approach towards a revolutionary line. Serrano Poncela and Carrillo and others regarded Largo Caballero as their champion and themselves as the ‘pioneers’ of his new line. ‘The emblematic figure of Largo Caballero’ was described, in terms that recalled the sycophancy of the Stalinist Bolshevik Party, as ‘the highest representative of a state of consciousness of the masses in the democratic republic, as the life force of a class party’.51

With the FJS experiencing a growth in numbers, many of them poorly educated, it was decided in 1932 to hold an annual summer school to train cadres. The sessions were to take place at Torrelodones to the north-west of Madrid. The second school was held in the first half of August 1933 with appearances by the major barons of the PSOE. Besteiro spoke first on 5 August with a speech entitled ‘Roads to Socialism’. It was obvious that his aim was to discredit the new extremist line propounded by Largo Caballero in the Cine Pardiñas. Insinuating that it was merely a ploy to gain cheap popularity with the masses, he condemned the idea of a Socialist dictatorship to defeat fascism as ‘an absurdity and a vain infantile illusion’. Without naming Largo Caballero, he spoke eloquently about the dangers of a cult of personality – which was precisely what Carrillo and the radical group within the FJS were creating around their champion. This might have been the fruit of genuine wide-eyed admiration on Carrillo’s part, but it also served his ambition. Moreover, this approach would later be repeated in his relationship with Dolores Ibárruri, better known as ‘Pasionaria’. Besteiro’s speech was received with booing and jeers. El Socialista refused to publish it. This was a reflection of the fact that the paper was now edited by Julián Zugazagoitia, a follower of Prieto who was sympathetic to the FJS and, for the moment, loyally followed the line of the PSOE’s president, Largo Caballero.52

The following day, 6 August, Prieto spoke. His language was neither as patronizing nor as confrontational as that of Besteiro, although he too warned against the dangers of easy radicalism. While defending, as Largo Caballero had done, the achievements of the Republic so far, he also spoke of the savage determination of the economic establishment to destroy the Republic’s social legislation. Nevertheless, he called upon the 200 young Socialists in his audience who dreamed of a Bolshevik revolution to consider that the weakness of the ruling classes and of the state and military institutions in the war-torn Russia of 1917 was simply not present in the Spain of 1933. He also warned that, even if a Socialist seizure of power were possible, capitalists in other parts of Europe were unlikely to stand idly by. It was a skilful speech, acknowledging that the FJS was morally justified in hankering after a more radical line, but rejecting such radicalism as practical PSOE policy. This was not what the assembled would-be cadres wanted to hear. Prieto was received with less outright hostility than Besteiro but the response was nonetheless cool, and his speech was also ignored by El Socialista.53

Largo Caballero was not at first scheduled to speak at the summer school. However, Carrillo informed him that the speeches by Besteiro and Prieto had caused great dissatisfaction and invited him to remedy the situation. Largo Caballero accepted readily, convinced that he had a unique rapport with the rank and file. In a somewhat embittered speech, he revealed his dismay at the virulence of rightist attacks on Socialist legislation and suggested that the reforms to which he aspired were impossible within the confines of bourgeois democracy. He claimed to have been radicalized by the intransigence of the bourgeoisie during his twenty-four months in government: ‘I now realize that it is impossible to carry out a Socialist project within bourgeois democracy.’ Although he affirmed a continuing commitment to legality, he asserted that ‘in Spain, a revolutionary situation that is being created both because of the growth of political feeling among the working masses and of the incomprehension of the capitalist class will explode one day. We must be prepared.’ Just as it alarmed the right, the speech delighted the young Socialists and shouts could be heard of ‘¡Viva el Lenin Español!’ The coining of the nickname has been attributed variously to the Kremlin, to Araquistáin and to Carrillo.54