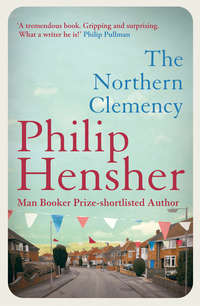

The Northern Clemency

‘We know all our neighbours,’ Barbara said with astonishment, ‘their birthdays, star signs, the lot. The telly programmes they watch, even.’

‘That’s because you live in a terraced house,’ Daniel said. ‘You could hear everything through the walls. When they fuck.’

‘Do you mind?’ Barbara said, objecting to the word rather than Daniel’s snobbery. But she drew close again, pulling him with her out of the light from the street towards the empty, overgrown garden.

‘They were all saying,’ Daniel murmured, his mouth against hers, running his tongue against her lips as they walked backwards into the lyric night, ‘they were all saying, who’s that gorgeous girl, goes into the neighbours’ gardens with Daniel Glover—’

‘They were not,’ Barbara said, her eyes bright, her hand running down Daniel’s side.

‘They were,’ Daniel said, his hand, his rippling fingers rising, weighing, cupping, down and under, beneath and within. ‘And I said—’

‘Oh, give over,’ Barbara said. But Daniel carried on, his hushed, exuberant voice now muted, and as they fell back against the lawn, which had grown into a thick meadow, she gave in to what he knew she felt. There was some indulgent amusement deep within him, and he never completely surrendered to the sensation, was never reduced to begging animal favours or further steps in the exploration of what she would grant him. His gratification, always, lay in seeing her so helpless; his pleasure in the expert and improving knack of bestowing pleasure. The noises she made were on some level comic, ‘Nnngg,’ she went, and an observation post in him kept alert over the expanding border territory between her propriety and her desire. They began when he chose to begin; they ended when he said he had to go, and when he knew that she would say disappointedly, ‘Do you have to?’

Barbara was in his maths set; he’d heard some of the things she’d been letting out about him. Flattering, really. He didn’t talk about her. Another couple of times, and that would be it; he’d seen the way Michael Cox’s sister looked at him, though she was eighteen next month. That would be something to talk about.

It was not clear to any of the Glovers what the purpose of the party had been. Not even to Katherine, whose idea it had been. He hadn’t come, after all. When the last of the guests had gone, the other two children went upstairs, Timothy holding a book. Malcolm sat down and, with his heels, dragged the armchair into a position facing the television. He did not get up to turn it.

Katherine put the letter on the shelf over the radiator, and began to go round the room, picking up glasses and plates. Malcolm had put the empty bottles in the kitchen as he had got through them. There were two open bottles left, one red and one white. The food had mostly been eaten, the tablecloth around the large oval dish of Coronation Chicken stained yellow where spoonfuls had been carelessly dropped. She began to talk as she collected the remains. She was wiping the thought that Nick, after all that effort, hadn’t come. He’d said he would.

‘They seemed to have a good time,’ she said. ‘I thought the food went well. I was worried they wouldn’t be able to eat it standing up, but people manage, don’t they?’

Malcolm said nothing. She sighed.

‘It’s a shame the new people over the road haven’t moved in yet,’ she said. ‘It would have been a good opportunity for them to meet the neighbours. Most people came, I think. There was a nice little letter from the lady in the big house, saying she was sorry she couldn’t come. She doesn’t like to go home after dark. Silly, really – it’s only a hundred yards, I don’t know what she thinks would happen to her, and it’s not really dark, even now. They get set in their ways, old people.’

Malcolm gave no sign of listening.

She couldn’t be sure what the reason for the party had been. But for her it had been defined by the people who hadn’t come rather than those who had. Not just one person; two of them. All evening she’d felt impatient with her guests who, by stooping to attend, had shown themselves to be not quite worth knowing. She projected her idea of the sort of friends she ought to have on to the new people – the Sellerses – and Mrs Topsfield, with the exquisite handwriting and supercilious reason for not attending. The Sellerses were going to be smart London people. That was absolutely clear.

‘Did you miss your battle re-creation society tonight?’ she said to Malcolm, to be kind.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘It doesn’t matter, once in a while.’

‘You could have invited some of them to come tonight,’ she said, although she’d rather not have to meet grown men who dressed up in Civil War uniforms and disported themselves over the moors, pretending to kill each other. It was bad enough being married to one.

‘I thought it was just for the neighbours,’ Malcolm said. ‘You said you weren’t going to invite anyone else.’

Upstairs, Jane shut her door. It was too early to go to bed, but it was accepted that she spent time in her room; homework, her mother said hopefully, but, really, Jane sat in her room reading. There were forty books on the two low shelves, and a blank notebook. She had read them all, apart from The Mayor of Casterbridge, a Christmas present from a disliked aunt; she had been told that Jane liked reading old books and that, with a life of Shelley, now lost, unread, had been the result. Jane’s books were of orphans, of love between equals, of illegitimate babies, treading round the mystery of sex and sometimes ending just before it began.

Her room was plain. Three years before she had been given the chance to choose its décor. Her mother had made the offer as the promise of a special treaty enacted between women, something to be conveyed only afterwards to the men. Jane had appreciated the tone of her mother’s confiding voice, but was baffled by the possibilities. It was that she had no real idea what role her bedroom’s décor was supposed to play in her mother’s half-angry plans for social improvement, and she was under no illusions that if she actually did choose wallpaper, curtains, paint, bedspread, carpet, even, that her choice would be measured against her mother’s unshared ideas and probably found disappointing. Would it be best to ask for an old-fashioned style, ‘with character’, as her mother said, a pink teenage girl’s bedroom? Or to opt for her own taste, whatever that might be?

In the end she delayed and delayed, and now her bedroom was a blank series of whites and neutrals. She had failed in whatever romance her mother had planned for her; and, with its big picture window, the room showed no sign of turning into a garret. It looked out on to a suburban street. Daniel’s room, at the back of the house, had the view of the moor, which meant nothing to him. Over her bed, one concession: a poster, bought in a sale, of a Crucible Theatre production of Romeo and Juliet. Daniel had seen it, not her – he’d done the play for O level. Someone had given him the poster, but it was over her bed that two blue-lit figures embraced, one already dead.

She wondered what the new people over the road would be like, and let her thoughts go on their romantic course.

It was the next day, in London. The house had been packed into a van. It was driving northwards, towards Sheffield. On every box was written, in large felt-tip letters, the name SELLERS.

‘Nice day for it,’ the driver said.

‘Yeah, you don’t want to be moving in the rain,’ the other man put in.

The driver was on Sandra’s right, his mate, the chief remover, on her left. On the far side the boy, ten or fifteen years younger than the others, who had said nothing.

‘Why do you say that?’ Sandra said. She was pressed up against the man on her left, and the driver’s operations meant that his left hand banged continually against her thigh. The lorry’s cabin was meant only for the comfort of three. There was a dull, dusty smell in the cabin, of unwashed sweaters and ancient cigarette stubs. The floor was littered with brown-paper sandwich wrappers.

‘Well, stands to reason,’ the chief remover said. ‘If it’s raining, that’s no fun.’

‘And there are always customers who insist on tarpaulins,’ the driver said.

‘Tarpaulins?’ Sandra said. ‘Whatever for?’

‘It’s their right,’ the chief remover said. ‘Say you’re moving a lot of pictures, or books, or soft furnishings—’

‘The customer, they don’t like it if you carry them out into the rain, and sometimes you have to leave them outside for a minute or two, and if it’s raining—’

‘Hence the tarpaulin,’ the driver said. Behind them, the full tinny bulk of the removals van thundered like weather. There was a distant rattle, perhaps furniture banging against the walls or a loose exhaust pipe. Below, the roofs of cars hurtled past.

‘Because,’ the chief remover said, ‘if something gets wet, even for a couple of minutes, if the whole load gets rained on, you get to the other end, see, and it’s offloaded and put in place, and a day or two later, there’s a call to the office, a letter, maybe, complaining that the whole lot stinks of damp.’

‘Hence the tarpaulin,’ the driver said again.

‘Course,’ the chief remover said, ‘nine times out of ten, it’s not the furniture, it’s the house, the new house, because a house left empty for a week, it does tend to smell of damp, but they don’t take that into consideration. But the tarpaulins, it doubles the work for us, it does.’

They were nearing the motorway now, having crossed London. The traffic that had held them steady on the North Circular for an hour was thinning, and the removals van was moving in bigger bursts. The car with Sandra’s parents in it, her brother in the back, had long been lost in the shuffle of road lanes, one moving, one holding; a music-hall song her grandmother used to sing was in her head: ‘My old man said follow the van…you can’t trust the specials like an old-time copper…’ No, indeed you couldn’t, whatever it meant.

She went back to being interested and vivacious before she had a chance to regret her request to travel up to Sheffield in the van, rather than in the car. ‘You must see everything in this job,’ she said vividly.

‘Yeah, that’s right,’ the boy surprisingly said, snuffling with laughter.

‘Don’t mind him,’ the driver said. ‘He can’t help himself.’

‘It’s a shame, really,’ the chief remover said.

‘A bit like being a window-cleaner, I expect,’ Sandra said, before the boy could say he’d seen nothing to match her and her jumping into the van like that. She was fourteen; he was probably five years older, but she was determined to despise him. ‘I mean, you get to see everything, everything about people.’

‘You’d be surprised,’ the chief remover said.

‘That’s the worst of it over,’ the driver said. The road was widening, splitting into lanes, its sides rising up in high concrete barriers, and the London cars were flying, as if for sheer uncaged delight, and the four of them, in their rumbling box, were flying too. ‘Crossing London, that’s always the worst.’

‘You see some queer stuff,’ the chief remover said. ‘People are different, though. There’s some people who, you turn up, there’s nothing done. They expect you to put the whole house into boxes, wrap up everything, tidy up, do the job from scratch.’

‘Old people, I suppose,’ Sandra said.

‘Not always,’ the driver said. ‘You’d be surprised. It’s the old people, the ones it’d be a task for, that aren’t usually a problem.’

‘It’s the younger ones, the hippies, you might call them, expect you to do everything,’ the chief remove said. ‘My aunt, you come across some stuff with that lot, things you’d think they’d be ashamed to have in the house, let alone have a stranger come across.’

‘That’s right,’ the boy said. He seemed almost blissful, perhaps remembering the boxing-up of some incredible iniquity.

‘Of course,’ Sandra said, ‘you’re not to know what’s in a lot of boxes, are you? There might be anything.’

The three of them were silent: it had not occurred to them to worry about what they had agreed to transport.

‘What was the place we said we’d stop?’ the chief remover said.

‘Leicester Forest East, wasn’t it?’ the driver said.

Sandra had watched the packing from an upstairs window, and only at the end had she thought of asking if she could travel with the men. She was fourteen; she had noticed recently that you could stand in front of a mirror with a small light behind you, approach it with your eyes cast down, then lift them slowly, and raise your arm across your chest, as if you were shy. You could: you could look shy. Whatever you were wearing, a coat, a loose dress, a T-shirt, or most often the new bra you’d had to ask your mum to buy to replace the one that had replaced the starter bra of only a year before, the shy look and the protective arm had an effect.

The old house had been stripped, and everything the upper floor had held was boxed and piled downstairs; the house had drained downwards, like a bucket with a hole. Sandra had been born in that house. She had never seen these upstairs rooms empty, and they now looked so small. Her clean room’s walls were marked and dirty. Only the window looked bigger, stripped of the curtains she had been allowed to choose and hadn’t liked for years – the pink, the peacocks, the girly rainbows and clouds. The net curtains were gone too – and if she had anything to do with it, they’d not be going up in her new room.

Her father was downstairs in the hall, telling the foreman a funny story – the confidential anecdotal mutter deciphered by bursts of laughter. Her mother, probably exhausted, was perhaps looking for Francis, who was lazy and clumsy, and had a knack of disappearing when anything needed to be done. She looked out of the window to where the van, its back open, was being steadily loaded with the house’s contents, exotic and unfamiliar when scattered across the drive. There were two men, one middle-aged, the top of his bald head white and glistening like lard, the other a boy. She waited in the window patiently, and soon her mother came out with cups of tea. The boy turned to her mother. He was polite, he said, ‘Thank you, Mrs Sellers,’ and when her mother went back inside, he was still facing in the right direction. She did that thing she knew how to do, and it worked; he looked upwards. Her gaze was shy, lowered. It met his modestly, and she gently drew her hand across her chest. Brilliant. She might have slapped him, the way he turned away, but he was the one who blushed. She realized that the driver and Mr Griffiths from next door, nosing about in his front garden, had also seen her. Mr Griffiths, who’d always been fond of her, and Mrs Griffiths too; from the look on his face now, they’d have something to think about if they ever thought of her ever again.

‘Have you seen your brother?’ her father said, as he thudded up the stairs.

‘No,’ Sandra said. ‘He’s probably down the end of the garden. Can we—’ she began. She was about to ask if they could have a tree-house at their new house, but she’d had a better idea. She was fourteen. ‘Can I go up to Sheffield with the movers in their van?’

Bernie looked startled. ‘There’ll not be room. A bit of an adventure, is it?’

‘Something like that.’

‘I’ll see what I can do. Don’t ask your mother. She’ll have a fit.’

So there she was, wedged into the van, clear of London, for the sake of the boy she had glimpsed – a movement of the arms, a flash of blue from the deep-set shadow under the surprising blond eyebrows. But he was saying nothing, and she was settling for enchanting the driver and the chief remover.

‘People do this all the time,’ she said.

‘Move house?’ the chief remover said. ‘Enough to keep us busy.’

‘No, I meant –’ But what she had meant was that people leave London by car, drive on to the motorway, set off northwards all the time, perhaps every day. She never had, and her mother, her brother and she had only ever left London when they went on holiday. She had never had any business outside London. ‘People either move a lot or not at all, don’t they?’ she said. ‘I mean,’ sensing puzzlement, ‘there’s the sort of people who never leave the house they were born in and die there. Dukes. And there’s the sort of people who move house every year, every two years. I don’t know what would be normal.’

‘The average number of times a person moves house in his lifetime,’ the boy said, ‘is seven, isn’t it?’ He had a harsh, grating voice, a South London voice not yet settled into its adult state.

‘Take no notice of him,’ the driver said. ‘He’s making it up. He doesn’t know.’

‘But the figure is increasing all the time,’ he continued.

‘He makes up statistics,’ the chief remover said. ‘That’s what he does. Once we were dealing with a musician, moving house for him – a sad story, he was divorcing his wife, and we had to go in and pick out the things that were going and the things that were staying. And we were moving his stuff and he said he’d be taking his cellos, because he had two, with him in a taxi, and wouldn’t let us touch them, though we handle your fragile things all the time. And all of a sudden this one says, “There are a hundred and twenty-three parts in a cello,” as if to say, yes, it’s best you handle it yourself. He’d only gone and made it up, the hundred and twenty-three parts. There’s probably about thirty.’

‘It sounds about right, moving seven times,’ Sandra said. ‘There’s a girl in my class who’s moved house seven times already. She’s only fourteen.’ Sandra thought she might have told them she was sixteen: she sometimes did that. Even seventeen. ‘This was two years ago,’ she added. ‘So she’d used up all her moves already, if you look at it like that.’

‘Fancy,’ the boy said.

‘Do you see that sign, young lady?’ the driver said. ‘A hundred and twenty miles to Sheffield.’

They were clear of London now; the banked-up sides of the motorway no longer suggested the outskirts of towns, but now, behind stunted trees, there were open fields, expansive with scattered sheep. In the distance, on top of a hill like a figurine on a cake, there was a romantic, solitary house. She wondered what it must be like to look out every morning from your inherited grand house and see, like a river, the distant flowing motorway. It was never empty, this road.

‘New home,’ the chief remover said sweetly. ‘Sheffield. And The North, it said.’

‘Have you ever noticed,’ the driver said, ‘that wherever you go, anywhere, you see motorway signs that say “The North”? Or “The South” when you’re in the north? Or “The West”? But wherever you go, and we go everywhere, you never see a sign which says “The East”?’

‘No, you never do,’ the boy agreed.

Sandra felt her story hadn’t made much of an impression. It was difficult, squashed in like this, to push back her shoulders, but she tried.

‘This girl,’ she went on, ‘you always wondered whether it was good for her to move so often. I mean, seven times, seven new schools. She never stayed long, so I don’t suppose she ever made proper friends with anyone. I tried to be friends with her, because I thought she’d be lonely, but she didn’t make much of an effort back. She’d only been in our school for three, four weeks when we found out the sort of girl she was.’

‘What sort was she?’ the boy said.

‘At our school, see,’ Sandra said, ‘you didn’t hang about after school had finished. Because next door there was the boys’ school. And maybe some girls knew boys from the boys’ school – if they had brothers or something – but this girl, I said to her one day, “Let’s walk home together.” And she said to me, “No, let’s hang around here and see if we can bump into boys because they’re out in ten minutes.” We didn’t get let out together, the boys’ school and girls’ school. And she jumps on to the wall, sits there, grins, waiting for me to jump up too. Because she just wanted to meet boys. That’s the sort of girl she was.’

‘Dear oh dear,’ the driver said. She had hoped for a little more concern: the older men might have had daughters of their own. The levity of the sarcastic apprentice had spread to them.

‘So you didn’t stay friends with her, then?’ The chief remover pushed back his cap and scratched his bald head.

‘No,’ Sandra said. Sod them, she thought. ‘Five months later, she had to leave the school because she’d met a boy and gone further. In a way I don’t need to specify—’ the adult phrase rang well in her ears ‘—and she had to leave the school because she was having a baby. Can you imagine?’

‘No,’ the driver said. He almost sang it, humouring her, and now it was over, the whole invented rigmarole seemed unlikely even to Sandra. ‘Probably best for you to leave a school where things like that go on.’

‘That’s right,’ the chief remover said, very soberly, looking directly ahead.

‘That’s right,’ the boy said. He plucked at his chin as if in thought. But he was trembling with laughter; the big blue van at their backs rumbled and trembled with suppressed laughter.

The blue pantechnicon, ahead of Bernie, Alice and Francis, formed a hurtling, unrooted landmark.

‘I don’t know which way he’s heading,’ Bernie said. ‘Expect he knows a route.’

Alice opened her handbag, brown leather against the brighter shine of the Simca’s plastic seats. She popped out an extra-strong mint for Bernie and put it to his mouth, like a trainer with a sugar-lump for a horse – he took it – then one for herself. They were on Park Lane. The van was a hundred yards ahead – no, that was a different blue van. Theirs was ahead of it.

‘We don’t need to follow them all the way,’ Bernie said, crunching his mint cheerfully. ‘We could be quicker going down side-streets. They’ll be sticking to the A-roads through London.’

‘I’d be happier, really,’ Alice said. That was all. Everything she had, everything she had acquired and kept in her life, had gone into that van – the nest of tables they’d saved up for, their first furniture after they had married, the settee and matching chairs that had replaced the green chair and springy tartan two-seater Bernie’s aunts had lent them…

‘That’s all right, love,’ Bernie said. ‘If you want to keep them in view, we’ll keep them in view.’

…the mock-mahogany dining table and chairs, green-velvet seated, from Waring & Gillow, brass-footed with lions’ claws, the double divan bed only a year old – their third since she had first come home with Bernie, him carrying her over the threshold and not stopping there but carrying her upstairs, puffing and panting until he was through the door of their bedroom and dropping her on to his surprise, a new-bought bed, and her not knowing she was pregnant already – and the carpets…

‘I know it’s silly,’ Alice said, ‘but I won’t feel easy about it unless we follow them.’

‘Well, we’ve lost them now,’ Bernie said. ‘We’ll catch up.’

It was true. London had spawned vans ahead of them, blue and black and green, rumbling and bouncing to the street horizon; the Orchard’s van was there somewhere, but lost. They ground to a halt in the dense traffic.

‘It can’t be helped,’ Alice said bravely. The carpets, all chosen doubtfully, all fitting their space. (She had no faith in the Sheffield estate agent’s measurements. The woman bred Labradors, which she’d mentioned more than once when she ought to have been paying attention.) The unit for the sitting room, a new bold speculation, white Formica with smoked brown glass doors, the Reader’s Digest books, the china ladies, the perpetual flowers under glass; the mahogany-veneer sideboard, a wedding present, once grand and solitary in the sitting room before furniture started to be possible for them; curtains, yellow for the kitchen, purple Paisley in the sitting room, red in their bedroom, the rainbow pattern Sandra had chosen…

‘Look on the bright side,’ Bernie said. ‘If they do get lost, or if they steal it and run away to South America, Orchard’s can buy us a whole new houseful of furniture. Insurance.’

‘They aren’t going to lose it, are they?’ A voice came from the back seat. It was Francis; even at nine, his knees were pressing hard into his mother. Goodness knew how tall he’d grow.