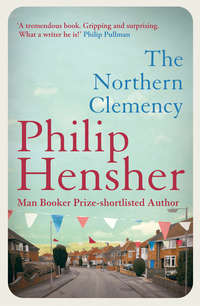

The Northern Clemency

‘You didn’t want to go into the law?’ Katherine said.

‘Well, I did for a bit,’ Nick said. ‘My brother went into a bank in the City, in London, and he’s done very well. Legal adviser. In New York for five years, but he likes it there. I think he’ll stay. Met an American girl, too.’

‘I used to work for a solicitors’ firm in town,’ Katherine said. ‘Before the children were born.’

‘That’s what I did, for a bit,’ Nick said. ‘I went to law school in Guildford after Sheffield, and then I got a job in London, big firm. Didn’t really suit me, though.’

‘That was a good job,’ Katherine said. She couldn’t help it. Sometimes she talked with Malcolm’s views.

‘Oh, I know,’ Nick said. ‘Ghastly. I did it for five years, and by the end of it, I was a sort of expert on this one tiny corner of the law. I won’t bore you with the details – it was something to do with industrial-property law. It came up all the time, and the answer was always the same, so whenever anyone found themselves in this one sticky situation, they’d be recommended to come to Oldman’s, who had an expert in the subject, meaning me, and I’d give them the same answer I’d given someone else the month before. And they’d pay some enormous fee, and I’d go home to my lovely flat in Little Venice – charming, you know, but quite a stink by the end of a hot summer – and have deep existentialist thoughts about the nature of existence. Well, after five years, I was reading Kierkegaard, not quite in the office, but nearly.’

A lot of this was obscure to Katherine. ‘I know what you mean,’ she said.

‘But in the end it was my dear old aunty Joan who came to the rescue. She died and left me a chunk of her money. I suppose she was still thinking of me as a nice little boy with perfect manners and curly blond hair and a velvet suit at tea on Sundays.’

‘Did you have curly blond hair?’ Katherine said. ‘How sweet.’ She looked, unable to help herself, at Nick’s hair now: tousled but, yes, curly, blond.

‘Perhaps not the velvet suit,’ Nick said. ‘My father, of course, was furious – he’s a lawyer too, great big house in Barnes, wanted us to follow in his footsteps, but I thought, One money-making lawyer’s enough. I’m going to sell the flat in Little Venice, take Aunty Joan’s money and go –’ he pulled a face and threw his hands up in mock horror ‘– into trade. Bugger.’

‘I could have told you that would happen if you didn’t put the coffee down first,’ Katherine said tranquilly.

‘It’s gone everywhere. Where’s that cloth?’

‘By the sink, where it should be. And your brother?’

‘Oh, Jimmy? Well, he was tickled by the idea, and I dare say he wanted to annoy the old man, too, so he put some money in. He just wants a finger in the pie. He was always like that, even when we were little boys, wanted to establish the rules of the game himself before we started playing.’

‘And your mother?’ Katherine said.

‘She died,’ Nick said. ‘Years ago.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Katherine said.

‘It was years ago,’ Nick said.

He was not one to accept sympathy, she found out. There were a couple of other incidents when, over the flowers and a cup of coffee in the morning, she tried to offer sympathy, and was rebuffed, first with surprise and then with faint amusement, as if his predicament were more of a shared joke than anything else. She had the impression, for instance, that his relationship with his father was difficult and oppressive, a Marxist nightmare of exploitation and liberation; Katherine had little idea of what Little Venice and Barnes might mean. ‘He’s not as bad as all that,’ Nick said. ‘He’s quite looking forward to coming up some weekend, actually, to see the shop. My brother said he said, “Well, at least someone in the family’s going to be making some money in an honest way,” as if I was going into the manufacture of – I don’t know – steel things, whatever they make in Sheffield.’

‘How hilarious,’ Katherine said. It was something Nick said. And the discovery of Nick’s response to sympathy there, or over his dead mother or, another instance, over a faintly outlined tale of unsuccessful love, was only one of several things she learnt about him. She was mastering the subject of Nick in pieces, from his favourite biscuit to the envisaged beauty of his future life, and she rehearsed it to herself on the daily bus ride home, on the fifty-one, as if it were her forthcoming specialist subject on Mastermind. Rehearsed it, too, in front of her family over dinner each night.

Jane could see that her mother was making a mistake with this. The rhythms of their day had been firmly established: she and Timothy would get on the same bus, the fifty-one, her with her friends and he with his friend, Antony, who lived just down the road. Two stops after, Daniel would get on, his school tie pulled down, a huge fat knot on his chest and just an inch or two of tie poking out, his black sports bag slung round his shoulders – she’d be getting on there next year, when she went to Flint. They ignored each other, Daniel with his noisy friends talking smut or football noisily, evicting the kids who didn’t know better than to bag the back seat on the top deck. It was only when they were walking down the muddy track after they’d got off the bus at the top of the road that they coagulated, usually after Daniel had cast a few showy insults their way. But then they’d be home, and there would be Mother, too, having started cooking dinner, the house bright and tidy. They all had keys, even Tim, but they hadn’t often used them.

That had changed, and now, when they got home, they opened up the house themselves, and it was grey and preserved from the morning, the breakfast things still in the sink, like an abandoned catastrophe. At first they were bewildered, at a loss, then afternoon television, children’s television, rose up like an appalling colour possibility; the telephone, too, which they fought over like rats. And there was, too, the possibility of bickering, always there but never quite bursting out in this way. Bickering: it was mostly tormenting poor Timothy, who nevertheless hardly seemed to suffer, just to accept leadenly the complex feints of Jane and Daniel’s mockery. Too often, even Jane thought, after a few weeks of her mother’s new job, as Katherine returned, towards six, she must have been greeted with three lined-up children, two faces sweetly composed, hands behind their backs, a third’s red and recently washed with a thoroughness surely slightly suspicious.

But if Katherine was suspicious, she did not show it, and her ‘I wish you two would leave Timothy alone’ survived – survived for years, in fact – only in their private exchanges, like a parrot-learnt and comic phrase from a school language that survives fossilized into adulthood when all possibility of expansion into grammatical expression has disappeared. Something decisive had changed when, a few weeks in, their mother came through the door, a little tousled but with a careless glow to her beyond what the weather could bestow, to be greeted with exactly this butter/mouth tableau, and said only, ‘How hilarious.’ A phrase Jane knew to be a possible expression but had never heard from her mother before and, reading its origins correctly, found there were more things to blush over than shame at having given your younger brother a Chinese burn while the elder sat on his chest.

But life was quickly full of such embarrassments. She wondered her father was not touched by it. Jane had learnt a lesson in behaviour from Daniel. That year, there had been a new girl at school. There were Indians in Sheffield, you saw them often in town, but they were poor and lost-looking and Ajanta was not like that.

‘My father,’ she said, on her first morning, ‘is a professor at the university.’ She said that, just going up to them in the playground at the first break, not waiting to be invited or anything. They’d been about to play a round of Witches and Fairies, but the plan evaporated. Anyway, they all felt a bit too old for that.

‘Where are you from?’ Anne, always the quickest to nose, said.

‘Bombay, originally,’ Ajanta said, ‘but we’ve been in America the last three years.’

‘Bombay,’ Anne said. ‘Where’s that when it’s at home?’

‘It’s a city,’ Ajanta had said, not put off, ‘in the south of India. Have you heard of India?’

‘Have you got brothers and sisters?’ Jane found herself asking.

‘Yes,’ Ajanta said. ‘I’ve got a sister. She’s going to Flint – is that what it’s called? And there’s my parents and Meena.’

‘Who’s Meena?’ Anne said deridingly, trying still to recoup some credit.

‘She’s my nurse,’ Ajanta said.

‘Your nurse? Are you ill or summat?’

‘No,’ Ajanta said. ‘You must know the use of the word “nurse”, to mean nursemaid. We say ayah. She’s a sort of family servant.’ Awed, they fell back.

But it hadn’t been long – the other side of an alarming birthday party, full of strange puddingy slices, covered with glitter you didn’t know whether to eat or not, and everything brought in not by Ajanta’s heavy-lidded mother, smoking away on the telephone, but by the tiny Meena who Anne, irretrievably, had mistaken for her – before the subject of Ajanta had taken over Jane’s conversation at home. What she said, what they ate, what Mrs Das had said about the standard of teaching in the West, as she confusingly called Sheffield, the games they had played and what Bombay was like, all a substitute for talking about Ajanta herself. She hadn’t been aware of it; it was only when Daniel and, amazingly, Tim had launched into a derisive chorus of ‘Ajanta says, Ajanta says,’ that she realized she’d been talking about her for days, weeks. It was something you ought to keep to yourself, whatever the something was you were immuring. She knew that now, at the cost of her besotted friendship – because, of course, you couldn’t go on as you had before, even in the playground where Daniel and Tim weren’t watching. The observation followed you even there. Ajanta herself hadn’t seemed all that bothered, or even to have noticed. But it was something you had to discover. You just didn’t talk like that. She’d found that out now.

But her mother, apparently, had never found that out. Here she was, night after night, talking about the flower shop, the day she’d had. It was like an itch in your nose, and you didn’t want to watch someone picking his nose over dinner. It was worst on Saturdays and Sundays when she didn’t work: she kept at it all day.

‘That’s looking nice,’ she said, coming up behind Malcolm, down on the lawn in kneepads. He was tugging at some weeds with a gardening fork, his gardening shirt on. It was a sunny day. Jane was sitting at the table on the patio with a book, the Chalet School; it was getting to an exciting bit, the new girl trapped by a sudden avalanche in a mountain hut with the strict history mistress and nothing but a few dry biscuits to see them through. Her dad had gone out early, and was working round the beds steadily, anti-clockwise, like a battery-powered machine. He’d got to about ten o’clock on the semi-circular dial. She paused, and paid attention.

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘The hostas, they’re doing well this year. Kept the slugs off for once. That trick with the orange peel seemed to do the trick.’

‘That’s a good job,’ her mother said. ‘It looked terribly untidy, all those bits of peel scattered all over the place. At least it’s serving a useful purpose. That’s lovely, too, isn’t it?’

‘The clematis? Yes, it’s had a good year. You never quite know with clematis.’

Her mother hummed a little tune. She was on the verge of saying something. She ran her fingers through the climbing plant growing over the fence, the foaming purple; she raised it to her nose, and let it drop. There was no scent. Jane knew that.

‘Did we never think of growing lilies?’ her mother said.

‘What’s that?’ her father said. Her mother repeated herself.

‘No,’ he said shortly. His voice was harsh with physical effort; his face, turned down, was flushed. ‘I never did. They come up, and they die off. Not much of a show, unless you’ve a lot of them, and nine-tenths of the year they’re nothing much to look at.’

‘I love them,’ her mother said. ‘Nick does very well with them.’

‘Who does?’

‘Nick,’ her mother said. ‘They’re very popular – they have a lovely scent for the house. Or there are gorgeous ornamental grasses you can grow now. Or honesty – you know what I mean by honesty? Even tulips. I love a big show of tulips.’

‘We have tulips,’ her father said. ‘Over there. Can always put some more in, if you fancy.’

‘I’d forgotten about the tulips,’ her mother said.

‘It’s not the time of year for them,’ her father said. ‘They were doing well six months back. I’m surprised you forgot.’

‘We’ve got such a lot of tulips now in Nick’s shop,’ her mother said. ‘You forget about when things bloom naturally.’

‘They’ll be forced,’ her father said.

‘I suppose that’s right,’ her mother said. She stood, irresolute. Jane’s father carried on tugging at the perhaps non-existent weeds, never having turned to look at her; and in a moment she went back into the house. She’d find nobody to talk to about Nick in there, Jane thought. She patted Jane’s head absently as she passed.

Jane thought the situation through, and decided the best way to deal with it. Anne was still sort of her best friend. A week or two later, after school, they went round to Anne’s house. She lived in Lodge Moor, in a modern house, brick-yellow, surrounded by innumerable stunted shrubs planted by the original builders. The ill-fitting windows rattled all year round with the ferocious wind. They went up to Anne’s bedroom: she was allowed to put posters up with sellotape, and her walls were lined with images of big-eyed brown horses, on which Anne was mad, and two or three pop-singers, just as glossy in their brown big-eyed gaze.

‘My mum’s having an affair,’ Jane said, once the door was closed.

‘An affair?’ Anne seemed frightened but impressed.

‘It’s happening everywhere, these days,’ Jane said, and sighed. ‘I only hope it won’t lead to divorce. It would break my heart if my parents split up.’

‘Who would you live with?’ Anne said.

‘I don’t know,’ Jane said. She hadn’t thought things out this far.

‘It’d be your dad,’ Anne said. ‘Your mum’d be off with her fancy man. It’d be all her fault – you wouldn’t let a woman who’d done that walk off with the children too. It’d not be fair.’

Jane let the full, lovely tragedy wash over her, its forthcoming bliss. She’d practically be an orphan, her and Daniel and Tim, coping bravely after a family tragedy; how they would look at her, when she moved up to Flint next year! ‘I don’t know,’ she said, honesty cutting in. ‘I don’t know that it’s come to talk of divorce yet.’

‘What’s your dad think?’

‘I don’t know that he knows,’ Jane said.

‘Well, how d’you know, come to that?’ Anne said. ‘You’re making it up.’ Then Anne got up, apparently bored with the subject. ‘Look at this,’ she said. ‘I got it down town on Saturday.’

She opened her white-painted louvred wardrobe doors. That was one of the things about Anne, along with her horses and her snappiness, her incredible wardrobe: there were things in there she’d grown out of, she having no small sister or cousin to pass things on to, all pressing against each other stiflingly. You couldn’t help but feel sorry for Anne’s clothes, suffocating each other in that breathless wardrobe. ‘Look,’ Anne said, and from the bottom of the wardrobe, she fished out a scrap of cloth, white and glistening, its price tag still on it even though it had been tossed to the bottom of the wardrobe, and a pair of strappy white shoes. ‘I got a halter-top and a pair of slingbacks from Chelsea Girl. The shoes were three ninety-nine.’

Jane didn’t know whether that was a lot or not. ‘Your mum go with you?’

‘Course she did,’ Anne said. ‘She paid. I’m going to put them on.’

She shucked off her school shirt. Jane looked, with envy, at her starter bra. Anne’s mother had bought it for her the first time she’d asked. No one else in their class had managed it, and Jane certainly not. But Anne didn’t have an older brother who’d overheard and laughed his head off. She put on the halter-top, twisting and fiddling with the strings behind. She slipped off the heavy brown school shoes, not untying the laces, and pushed on the slingbacks, squashing them on in a hurry, and then, striking a pose, the price tag dangling from her waist over the grey school skirt, she pushed forward her left hip and pouted. She twirled, the strap of her starter bra across her bare back.

‘Nice,’ Jane said.

‘Go on, you try them on,’ Anne said, and so they started to play, the lipstick coming out, the hairbrushes, the materials of femininity. Most of their afternoons turned to this.

‘I’m not making it up,’ Jane said, after a while, their makeup smeared, their outfits half on, half thrown off across the bed.

‘Making what up?’

‘My mum and her affair. I’m not,’ Jane said. ‘She talks about him all the time. She can’t stop herself. It’s like you and horses.’

‘Me and horses? What’re you talking about?’ Anne got up and peered into the mirror, admiring her face, this way and that.

‘It’s like the way, you know, you love horses, you, you’re mad about them, and all the time, it’s horses this, horses that.’

‘I thought you liked horses too,’ Anne said, drawing back a bit, offended. ‘I wouldn’t talk about them if you weren’t just as interested as I am.’

‘I am interested,’ Jane said, feeling that the conversation was getting away from her. ‘But you love horses, you.’

‘Yes, I do,’ Anne said. She sank to her haunches, clasping her knees to her chest like great adult breasts. ‘I’m not saying I don’t.’

‘So you talk about them, don’t you?’

‘If you say so,’ Anne said, not quite convinced.

‘Well, it’s like that with my mum,’ Jane said. ‘Every day it’s “Nick says this, Nick did that, Nick likes ketchup with his chips.”’

‘Everyone likes ketchup with their chips,’ Anne said. ‘That doesn’t prove anything, if you ask me.’

‘Yes,’ Jane said, gathering the logic of her case. ‘Yes, that’s it, though. If everyone likes ketchup on their chips, why’s she bringing up Nick especially? You see what I mean?’

‘You’re daft, you,’ Anne said, ‘I think you’re just romancing. Anyway, you don’t want your mum and dad to split up, do you?’

‘I don’t know,’ Jane said. ‘It’s nothing to do with me.’

‘Who’s this Nick, then?’

‘He’s her boss. She got a job, working in a flower shop. In Broomhill, it is.’

Anne sighed. She was eight months older than Jane: sometimes she took advantage of this difference to make an emphatic point. ‘I would say,’ she said heavily, ‘there’s nothing in it. I’m glad my mum doesn’t have to go out to work.’

‘My mum doesn’t have to either,’ Jane said. ‘She just wants to. I know what. I’m going to go down there one day after school, I want to have a look at him. Do you want to come?’

‘What’ll that prove one way or the other?’

‘Are you going to come?’

‘If you insist,’ Anne said, and then, from downstairs, her mother called something. She rolled her eyes. The call came again. She got up from her squatting position, and impatiently flung open the door. ‘What do you want?’ she shouted rudely.

‘There’s squash, girls,’ the polite voice floated up. ‘And biscuits. I know the sort you like.’

‘We’re busy,’ Anne yelled. ‘We’re talking about Jane’s mum. She’s got a lover.’

There was a short silence downstairs. Jane could feel herself blushing. ‘I wish—’ she said.

‘Oh, I’m sure she’s not, not really,’ Anne’s mum called. ‘There’s squash and biscuits. Shall I bring them up?’

But the idea of going down Broomhill the next afternoon had been agreed on. The next day they had geography last thing; Anne had volunteered the pair of them to put away the Plasticine contour map of Yorkshire the class was making, and the labelled cut-away of the strata of rock underneath a coal-mine. The task had been occupying them for weeks – it was supposed to be ready for Christmas Parents’ Day and they were all sick of it and Miss Barker’s shrill exhortations: ‘I don’t care whether it’s done or not, you’re only showing yourselves up.’ For weeks, as if it were tainting them with the nightmarish horror of its incompletion, there had been a rush to the door as the bell rang. But this evening Anne lingered, tugging at Jane’s skirt as she, like the rest, got up, slinging her bag over her shoulder. Miss Barker had been about to collar someone at random as usual, but, with a mistaken glitter in her eye, she alighted on Jane and Anne, fingered them as dawdlers for the punishment of putting the stuff away. Anne and Jane, they weren’t good girls – they’d already been done for giggling five minutes into one of her lecture-reminiscences, and would have been done worse if Miss Barker had known that Jane had giggled at Anne saying, ‘It’s her wants a lover,’ meaning Miss Barker. So she couldn’t have known that Anne’s dawdling was in aid of volunteering for the task, or at any rate – you wouldn’t want to show Miss Barker that much willing – allowing herself and Jane to be landed with it. Jane thought she might have been consulted – ‘There’s good girls,’ Miss Barker said when they were done, which was enough to make you puke – but she saw the point when they’d finished folding the plans, scraping the mess of the afternoon’s Plasticine off the tables, put the whole almond-smelling bright geologies back into 4B’s geography cupboard, and gone out, fifteen unhurried minutes after the end of school. It was as empty as a weekend glimpse; everyone had gone, swept off in the fifty-one bus. She and Anne shouldered their bags and turned in the other direction, of Broomhill, without having to explain to anyone, and that was a good thing.

All the schools were turning out: the big boys and girls from the George V in their standard black blazers, and the snooty ones, the girls in purple from St Benet’s, where you paid to go, like Sophy next door to Anne, where she claimed you got to learn Russian and, like drippy, bleating Sophy, to produce the horrible sheep-like noise of the oboe too. They were all heading in the same direction, the opposite one to Jane and Anne. Jane felt like a truant, the two of them in their ordinary clothes.

‘Do you think Barker cares?’ Anne said.

‘Cares about what?’ Jane said.

‘About Parents’ Day,’ Anne said. ‘She goes on about it enough.’

‘I reckon she’ll get the sack if it’s not ready,’ Jane said, ‘if it’s not perfect, that geology thing.’

‘I hope she does,’ Anne said. ‘We might get someone who doesn’t—’

‘“When I was in Africa,”’ Jane quoted, a favourite conversational opening of Miss Barker’s, liable to lead to any subject, and they laughed immoderately, clutching their stomachs and saying it three or four times.

‘She made me eat cabbage once,’ Anne said, ‘when she was sitting in the teacher’s place on our table at dinner. I hate cabbage.’

‘She’ll have had to eat worse in Africa,’ Jane said. ‘She’ll not have sympathy for you, being fussy over a plate of cabbage, when you think what she’s had to force down.’

‘Missionaries from a pot,’ Anne said. ‘I dare say.’

‘Worms and grubs,’ Jane said. ‘Toasted over an open fire.’

‘Only like marshmallow,’ Anne said.

‘Not much like,’ Jane said.

‘But cabbage, it’s horrible,’ Anne said. ‘She made me eat it, she said it didn’t taste of much. I think it tastes right horrible.’ Jane agreed, and they went on.

‘“When I was in Africa,”’ Anne quoted again, but she hadn’t thought of how it could go on after that and fell silent. Missionaries, cannibals, and that right funny film in Geography with a black man in a wig like a lawyer’s where they’d laughed and Miss Barker’d turned the lights up to talk in low serious tones about (one of) her disappointments.

There was the Hallam Towers on the left, and on the right, the gloomy ericaceous drive that led up to the blind school – there were dozens of blind children up there: you never saw them. And then the library, and then they were in Broomhill. It was a journey you took with your mum and dad, perhaps; it wasn’t a schoolday journey. So they were a little bit solemn as they turned the corner into Broomhill proper, with its parade of shops, marking not what they passed but what they were heading towards.