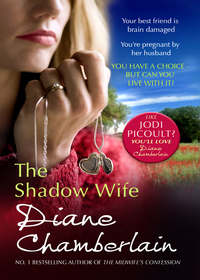

The Shadow Wife

“Hello, Joelle,” Sheila said with the cool edge to her voice that Liam had noticed recently when she spoke to—or about—Joelle. He worried that, somehow, Sheila knew that he and Joelle had become very close. Too close.

Sam instantly reached toward her, and Liam transferred the little boy from his arms to hers, his hand accidentally brushing her breast as he did so. He flinched inwardly at the touch, but Joelle pretended not to notice. She nuzzled Sam’s neck.

“Hello, sweetie pie,” she said. “How’s my boy?”

She smiled at Liam but quickly riveted her gaze on Sheila, and Liam understood. She, too, felt the discomfort in looking directly at him.

“How’s Mara this evening?”

Stupid question, Liam thought. Everyone knew how she was. The same as she’d been for months. But they all played the game, anyway.

“She’s full of smiles, as usual,” Sheila said.

“I’m afraid we wore her out, though,” Liam added. “I’m sorry. I forgot it was Thursday.”

“That’s all right,” Joelle said as she handed a squirmy Sam back to his father. “I’ll just sit with her. Hold her hand.”

“That would be nice,” Sheila said, and she proceeded past her through the doorway.

“See you tomorrow,” Liam said, following his mother-in-law outside.

Once on the sidewalk, he set his son down, and Sam started his toddling exploration of the landscaping.

“What’s with you and Joelle?” Sheila asked as they walked toward the parking lot.

“What do you mean?”

“I’ve picked up a little ice between the two of you lately.”

“Your imagination,” Liam said, but he was certain he heard some satisfaction in Sheila’s voice. He recalled some of his mother-in-law’s recent comments about Joelle: “She only comes to see Mara once a week,” she’d say. “And to think they had once been best friends!” Or, “I didn’t like that shirt Joelle was wearing today. It makes her look fat.”

Liam buckled Sam into the car seat, then stood up to give his mother-in-law a quick hug. “Thanks,” he said.

“My pleasure.”

“Hope I don’t need to call you again tonight.” He opened the driver’s-side door.

“I’m available if you need me,” she said, the warmth back in her voice. She waved bye-bye to her grandson through the car window, then turned to walk toward her own car.

Liam pulled into the street, turning in the direction of home, knowing he’d have to fix something to eat once he got there and feeling overwhelmed by the thought of that simple task. He hated this depressed feeling that had come over him lately. He’d made it through an entire year without Mara, the Mara he’d known and adored, and he’d been depressed but still strong and resilient. The one-year anniversary, though, had kicked him in the back of the knees. Two months ago had been Sam’s first birthday, the date that would always mark the moment Mara lost her body and mind, if not her spirit. The day that everything changed. Forever, said her doctors. She would never be the same. She would never be the woman he had fallen in love with.

He’d celebrated Sam’s birthday with Sheila and Joelle, none of them mentioning the other event marked by that date. There was something about a year that made it so final. A year of growing as a person, as a doctor, as a first-time mother. It had all been snatched away from Mara. And from him.

But despite his aversion to Sheila’s veil of denial, he would not allow himself to give up hope, and he pulled into his driveway with new determination. Once he’d fixed supper, washed the dishes and settled Sam into bed for the night, he would do what he’d been doing ever since the day of his son’s birth: he would log on to the internet and visit the website where people had written anecdotes about their friends and relatives who had suffered an aneurysm. And there he would find stories of hope. Stories of miracles. They would make him believe, if only for a moment, that the wife he still loved would one day be able to hold her son in her arms.

3

JOELLE LISTENED TO A NOVEL ON TAPE AS SHE DROVE TOWARD Berkeley and her parents’ home. She kept having to rewind it, because her mind was wandering, and finally she turned the tape off altogether. Fiction no longer seemed as gripping to her as her own life.

It was her father’s birthday, and she’d promised to make the two-hour drive to Berkeley to help him celebrate. Celebrate was probably the wrong word. It was to be a quiet dinner, just her parents and herself. Her parents weren’t much for birthdays. Gifts, for example, were not allowed. She had received no birthday gifts from her parents in all the thirty-four years of her life, although she’d received many gifts from them at other times. Her parents didn’t believe in giving because you were expected to, but rather because you were moved to. Nor did her parents believe in celebrating holidays. No Christmas. No Hanukkah. They attended some tiny Berkeley church, the denomination of which Joelle could never remember, that honored the sacred spirit in all of nature, and Joelle was never surprised to find a pot of dried leaves or a bowl of shells or fruit on the so-called altar in their so-called meditation room. No one was allowed in that room unless they were there to meditate. For two people who eschewed society’s rules and traditions, Ellen Liszt and Johnny Angel had created plenty of their own.

That was the way Joelle had been raised. She’d lived the first ten years of her life as Shanti Joy Angel in the Cabrial Commune in Big Sur. It was a time she remembered with remarkable clarity: eating a strictly vegetarian diet, worshiping nature, learning not to play too near the edge of the cliffs, the way some children learned not to play in the street. Growing up there, she’d taken the magic of Big Sur for granted. Sometimes now, though, she remembered it with longing. She missed the view of the bluffs carving their way through the blue and green water, the dark, cool forest, the ubiquitous fog that washed over them in the morning and late afternoon, which made games of hide-and-seek thrilling and scary. You never knew who or what was mere inches away from you. Her mother and a few of the other parents had taught the children in one of the cabins, the commune’s one-room schoolhouse, and by the time Joelle entered public school, she had been far ahead of her classmates.

She had been grateful, then, that she’d spent ten years in the commune. Her life there had given her skills that other children did not seem to have. She could talk with anyone, of any age group, about nearly any subject. The commune had provided her with nonjudgmental acceptance and plenty of fuel for her imagination. It had taught her to take care of other people, and she was certain that was one reason she’d become a social worker.

Somehow, though, over the last twenty-four years, she’d picked up the mores and conventions of the outside world and had made them very much her own. Maybe it was the talk she’d had with her parents when she turned thirteen, three years after they left the commune, that had influenced her. For some reason, her parents began confiding in her then, apparently deciding that thirteen was the appropriate age for that sort of conversation. They had believed in free love, they told her, the sharing of partners, as well as of food and clothing and chores, and that had been fine for both of them at first. But they began to feel that age-old emotion they had been trying to suppress for a decade: jealousy. As the feeling ate away at each of them, they decided it was time to leave, to rejoin the world. Maybe the way of the commune had not been intended for a lifetime, after all. Yet, although her parents were able to fit in easily in Berkeley, with its counterculture and free thinkers, Joelle doubted they could have adjusted to any other area of the country. In many ways, her parents, who had never married, were still the people they had been at Cabrial Commune.

Ellen and Johnny had accepted the fact that she wanted to change her name when she left the commune, although they never called her Joelle themselves. She’d combined her parents names, John and Ellen, and resurrected her father’s surname of D’Angelo. That her father still went by Johnny Angel seemed perfectly natural to Joelle, until she really stopped to think about it. Then, the goofy charm of it, of picturing her teenage father taking that handle for himself, made her smile.

Her father, now fifty-three years old, managed a coffee shop near the university, while her mother was a weaver, a beader, a massage therapist, a tarot-card reader and a part-time auto mechanic at the gas station near their house. And somehow, she managed to incorporate her varied talents into a business that brought in more money than Joelle’s father and his coffee shop.

Her parents had been on her mind a good deal these past two days. She supposed that was natural: If you learn you’re about to become a parent, you begin viewing your own parents in a new light. But that wasn’t the only reason she’d been thinking about them. She was beginning to toy with an idea, a way to have the baby and avoid hurting anyone in the process—with the possible exception of herself. She could leave the Monterey Peninsula. Leave Silas Memorial, her condominium in Carmel, everything. Leave that part of her life behind, move someplace else, have her baby, raise it in her new home, and no one in Monterey would ever have to wonder how she came to be pregnant and who the father of her baby might be. Most importantly, Liam would not be faced with a dilemma he could not possibly resolve. It was the right time to make such a move, she thought, and not just because of the baby. She’d lost her two closest friends in Liam and Mara; her other friendships in the area were shallow by comparison. So, she could move someplace new, where she could start over and build a fresh network of friends for herself.

It would be best, she thought, if she moved where she knew someone, and Berkeley, with her parents nearby, was a logical choice. Maybe she could even live with them for a period of time. She wasn’t sure how she felt about that, but tonight was not going to be the night she decided. She needed to sit alone with the idea of leaving Monterey for a while, just as she needed to keep her pregnancy a secret.

She arrived at her parents’ house just shy of six. She’d spent her teen years in this house in the Berkeley foothills, but as an adult, she saw it through different eyes. The house was diminutive and absolutely charming. It resembled a Mexican adobe, with its straight, angled roofline. The stucco was painted a color that fell somewhere between blue and white, and deep blue tiles flanked the front door and the large arched window of the living room.

Joelle parked in the driveway and walked across the small half circle of green grass to the front door, which was, as always, unlocked.

“Hello!” she called as she stepped into the small foyer. “We’re in here, Shanti,” her mother called from the kitchen.

The kitchen was at the rear of the house, and she walked into the room to find her father in an apron, skewering vegetables for kebabs, and her mother in jeans and a T-shirt, stirring a pitcher of lemonade. Both her parents were slender, sharp-featured and gray-haired, and as usual, they looked so happy with their lot in life that she couldn’t help but smile at seeing them.

“Hey, baby.” Her father set down the skewer he was working on, wiped his hand on the dish towel hanging from the refrigerator door, and pulled Joelle into one of his familiar bear hugs.

“Happy birthday, Dad,” she said, her head resting against his shoulder.

“Thanks for coming, honey,” he said, emotion in his voice. He was not a typical male, never one to hide his feelings, and she adored him for that.

“Shanti, I want to show you something.” Her mother grabbed her hand as soon as Joelle had let go of her father. “You’ve got to see what I made.”

She led Joelle out the back door and down the steps to the small yard.

“Look,” she said, pointing. “Up there.”

Joelle raised her eyes to see a birdhouse atop a pole in the center of the yard. She walked toward it for a closer look. The little house was an exact replica of her parents’, and she laughed.

“How did you do that?” she asked. “It’s adorable.”

“Oh, a little bit of paint and plaster and ingenuity. I’m hoping it will attract some songbirds.” Her mother stood next to her, her arm around Joelle’s shoulders, and Joelle suddenly felt her eyes begin to tear. Would she ever be able to give her child the unconditional love and devotion that her parents had lavished on her? She slipped her arm around her mother’s waist and rested her head on her shoulder with a sigh.

“What’s that about, love?” her mother asked.

“Just … a long week,” she said. “Glad to be up here with you and Dad. That’s all.”

“That’s plenty,” her mother said, giving her shoulders a squeeze.

She stayed in the yard for a while, surreptitiously wiping the tears from her eyes as her mother led her around the garden, telling her what vegetables and flowers she was planting this year. For the first time, Joelle thought it would be nice to have a small yard of her own, someplace where she could watch things come to life. She had never cared about that before, but suddenly she felt a need to dig in the earth, to get her hands dirty.

“Come and get it!” her father called from the patio, where he was grilling their dinner.

Vegetable kebabs, Joelle thought with a smile as she and her mother crossed the yard to the patio. What would her parents say if she told them she’d eaten liver this week?

They sat at the rickety, aging picnic table on the patio, talking about Joelle’s old Berkeley friends as they ate, running down the list of who was living where and doing what. Joelle slipped inside her own head as they talked, wishing she could tell them about her pregnancy, even if she was not ready to talk about a possible move to Berkeley. She knew they would not chastise or judge her, and they would support whatever choices she made for herself. They had been an incredible help to her during the divorce from Rusty, even though they had never understood her desire to marry him in the first place. He was too conservative, they’d said, too rigid, and ultimately, they’d been right.

Her parents’ solutions to her problems, though, were often not “of this world.” Her mother would probably load her up with herbs and teas and tell her which acupressure points she should stimulate, perhaps even talk her into having her tarot cards read. Joelle wasn’t ready for all that, and so she wasn’t ready to share her bittersweet secret with them. Instead, she found herself telling them about the patient whose baby had been stillborn.

“I feel terrible for her,” she said after describing the woman’s situation. Again, she felt her eyes burn with tears, and she knew that this time her parents noticed.

“You see things like that every day, honey,” her father said gently as he rested his empty skewer on the side of his plate, and Joelle thought he was eyeing her suspiciously. “You don’t usually get so upset over them.”

“I know,” she admitted. “I don’t know why this time it’s so hard for me. Maybe because they had fertility problems, and I can relate to that.”

“How did this baby die?” her mother asked, pouring more lemonade into her glass.

“They don’t know why it happened,” Joelle said.

“I just wondered if it might have been the cord. You know, like it was with you.”

Joelle shook her head with a smile. Leave it to her mother to imagine a metaphysical connection between this woman’s loss and her own problematic birth. She waited for the next words, wondering which of her parents would say them first. Her father, most likely.

“You should get in touch with the healer,” he said. Bingo.

“I knew you were going to say that, Dad.” She smiled at him with a mixture of affection and annoyance.

“So why don’t you ever take my advice about contacting her?” he asked.

“You know why.” She didn’t want to get into this with her parents tonight. To her way of thinking, healers were right up there with UFOs and magic tricks. “It’s hardly my role, as a medical social worker, to suggest that anyone engage the services of a healer,” she said. “That’s all.”

Her mother leaned forward, the expression in her blue eyes both serious and sincere. “If you’d been there the day you were born, you wouldn’t be so skeptical,” she said. “Well, you were there,” she added, “but you know what I mean.”

“Mom, I started breathing because I was lucky,” Joelle said. “Or maybe Carlynn Shire was holding me in a position that stimulated my taking in air. I doubt anything magical happened.”

“And what about all those other people she healed?” her father asked.

“You remember Penny, don’t you?” her mother asked, mentioning the name of one of the women who had lived in the commune.

“Penny was gone by the time Joelle was old enough to know her,” her father said.

“Oh, that’s true.” Her mother laughed. “She was only there about a year. Maybe even less. But, anyway, she’d lost her voice, and Carlynn gave it back to her. There were many other times she healed people. And there was that little boy who was written up in Life Magazine.”

Joelle was afraid they might pull out the old issue of Life, which they’d found in a used bookstore and kept preserved in a plastic wrapper. She vaguely remembered them showing her the yellowed article at some time over the years. Long before Joelle’s birth, Carlynn Shire had supposedly healed a sick little boy, who turned out to be the son of someone who worked on the magazine. That someone wrote a glowing article about her, which apparently launched Carlynn Shire’s fame and fortune.

Sliding the vegetables off one of the skewers, she listened to her parents tell their stories about Carlynn Shire, and quite unexpectedly, she saw Liam’s face in her mind. She saw him with Mara in the nursing home, where he would touch his wife with affection, making himself smile at her when he felt anything but happy. It broke Joelle’s heart to see him that way. There had always been so much love in Liam’s eyes when he was with Mara, and that love was still there these days, although Mara couldn’t return it with anything more than puppy squeals. Then there was Sam and his ingenuous acceptance of his mother just the way she was. Soon, he would realize what he was missing. Soon he would be old enough to be embarrassed about it.

She’d lost track of the conversation and nearly jumped when her mother put a hand on her arm. “Are you with us, honey? You look like you’re a million miles away. What’s troubling you, love?”

Joelle drew in a long breath. “I was thinking about Mara,” she said. “If anyone deserves a miracle, it’s her.”

“Mara’s perfect for Carlynn Shire to work with,” her father said.

Joelle felt like screaming in frustration at his one-track mind, but she managed to make her voice even as she responded. “You haven’t seen Mara since the aneurysm,” she said. Her parents knew Mara quite well. Over the years, Joelle had brought Mara to Berkeley with her several times. “The doctors say she’ll be this way forever.”

Her father leaned toward her. “What do you have to lose by going to see Carlynn Shire?” he asked.

“I’d feel like an idiot,” she replied.

“And if there’s the slightest chance Mara could be helped,” her father said, “wouldn’t that be worth feeling like an idiot?”

“Of course, but …” She shook her head. “I doubt people can just call her up and ask her to heal someone.”

“But if you told her who you were,” her mother said. “If you told her you were that baby she saved in Big Sur thirty-four years ago, I bet she would—”

“Although,” her father interrupted, “she might not want to be reminded of that time.”

“Why not?” Joelle was puzzled.

“Because of the accident,” her mother said.

“Oh.” Joelle had heard the story any number of times, but she had never really listened. She knew what she was risking by asking her parents to repeat it to her once again—they would go on and on and on—yet suddenly she had a real desire to know.

“Remind me,” she said. “What happened, exactly?”

“Carlynn and her husband—”

“Alan Shire.” Joelle recalled his name from the previous recitations of this tale.

“Right. They were both doctors. And Carlynn had the gift of healing. Alan Shire didn’t, but he was very interested in that sort of phenomenon. So they founded the Shire Mind and Body Center to look into the phenomenon of healing.”

Joelle knew the center still existed and was somewhere in the vicinity of Asilomar State Beach. It was viewed with skepticism by the medical establishment and with total credibility by California’s alternative practitioners.

“Yes,” her mother said, “but they didn’t call it that back then. What was it called?”

Her father looked out toward the new birdhouse for a moment. “The Carlynn Shire Medical Center,” he said.

“Right,” said her mother. “It was just getting off the ground then. Penny Everett showed up at the commune one day, without a voice. She came there to get away from stress, because her doctor said that was what was causing her hoarseness.”

“She went on to be in Hair,” her father added.

“Who did?” Joelle was getting confused. “Carlynn?”

“No, Penny,” her mother said. “And she knew she couldn’t get a part in Hair if she had no voice. She’d been an old friend of Carlynn’s, and so she called Carlynn and asked her to come heal her voice. Carlynn dropped everything and came down to the commune.”

“Of course,” her father added, “we always believed some other force brought her there right at that time, because it was just the day after she arrived that you were born. If she hadn’t been there, you wouldn’t be here now.”

The thought made her shudder despite her skepticism.

Her father continued. “So, she’d been there a few days when—”

“A whole week,” corrected her mother. “That’s why Alan Shire and her sister were so freaked out.”

“Whatever,” her father said. “She’d been there a while, and of course we had no phone or any way for her to reach her family without leaving the commune, so I guess her husband and sister got worried about her and drove down to Big Sur to find her.” He looked at his wife. “What was the sister’s name?” he asked her.

“Lisbeth.”

“Oh, right. Alan Shire and Lisbeth, the sister, got a cabin over near Deetjen’s Inn—remember Deetjen’s?”

Joelle nodded quickly, wanting him to get on with the story.

“They checked into the cabin,” he said, “then started looking for the commune. We weren’t the only commune in Big Sur, as I’m sure you remember, and they probably didn’t know where to start looking. It was dark, I guess, by the time they got to the right one.”

“Actually, it was only Alan who got there,” her mother said. “The sister had stayed behind in the cabin.”

“That’s true. And Carlynn was in Penny’s cabin then, but she’d been in our cabin just an hour or so earlier. Rainbow.” He grinned. “Remember it?”

“Sure.” She smiled at the memory of the small, dark cabin. She could smell it right at that moment—the scent of ashes mingled with the earthy, musky odor inevitably present in a wooden cabin surrounded by trees and fog. What a strange existence she’d had for the first ten years of her life!

“We’d had her come over to Rainbow a couple of days after you were born because we thought you were running a fever,” her father continued.

“You thought she had a fever,” her mother corrected him. “I still think she did,” her father said. “I think it disappeared as soon as Carlynn touched her.”

Even Joelle’s mother shook her head at that, but Joelle felt moved. Her father had always been a nurturer, and she liked to picture him, a kid of nineteen, skinny little Johnny Angel, aching with worry over his baby girl.

“Well, anyhow,” her father said, “she went back to Penny’s cabin after curing you—” he winked at her “—and Alan Shire showed up and spirited her away without letting her even say goodbye.”