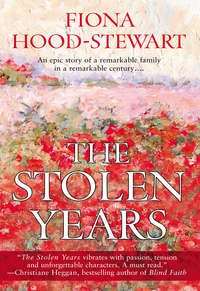

The Stolen Years

“But Tante, if no nurses or V.A.D.s went to the front, what would happen to all the wounded? What if Gavin or Angus were hurt and there was no one to tend to them?” Flora appealed softly.

“I know, ma chérie. I…” Constance raised her hands in a Gallic gesture of defeat, lips quivering as she shook her graying head and sighed. “But you are so very young, ma petite. There is so much of life you don’t know yet, things you are not aware of, ought not be exposed to. Girls should not have to go to the front with the men. It is not at all seemly.” She gave another long sigh that expressed better than words all the pain and anxiety, the keeping-up of a brave front while praying fervently that the ominous telegram beginning with those fateful words—We sincerely regret to inform you…—would never arrive.

“It won’t be for long, Tante.” Flora reached across the table and gently touched her aunt’s trembling fingers. “I’m sure the war cannot last much longer.”

“How can we tell?” Tante Constance pressed a hankie to her eyes, trying to hold back the tears. “How do we know how much longer? They say in France that General Nivelle has all these wonderful plans, but all the while, the army is refusing to fight. My brother Eustace writes that were it not for the astute intervention of a young officer named Philippe Pétain things would be a disaster. And look at this country! Lloyd George argues with General Haig and that Robertson man, and everything remains exactly the same, more young men dead or wounded, more widows and weeping mothers. Have they no hearts?” she cried. “You are like a daughter to me, Flora dearest.” She clasped the outstretched hand. “I could not bear to lose you, too. Oh, mon Dieu, non!”

“My dearest,” Hamish said soothingly, “we must all be prepared to make the supreme sacrifice for the good of the nation. Or there will be no nation,” he added dryly.

Flora stroked Tante’s tremulous hand, wishing she could offer solace. She hated being the cause of more suffering, yet she knew she had no choice. She glanced at Uncle Hamish, struck all at once by the irony that this war that they all deplored was multiplying his fortune several times over. The need for British coal was overwhelming and Hamish’s factory could provide it. But she knew he would gladly have given every last penny to have his sons returned to him safe and sound.

That night they played cards in the drawing room as they had before the war. Little had altered at Midfield, as though defying the onslaught of change that would inevitably come. Here, a few miles south of Edinburgh, the war seemed a remote happening that had afflicted but not yet debilitated. Rationing wasn’t felt the same here; Uncle Hamish had arranged for eggs, butter and lamb to be brought from Strathaird, the estate on the Isle of Skye where the family used to spend a large portion of the summer holidays before embarking on an annual trip to Limoges. There Tante Constance’s brother, Eustace de la Vallière, and his wife, Hortense, owned la Vallière, one of the largest porcelain factories in France.

Flora gazed at the green baize of the card table and thought of Cousin Eugène, Oncle Eustace and Tante Hortense’s son, so serious, spiritual and mature despite his youth, entering the priesthood. It had been three long years since they were all together. She tried to concentrate on the game, making sure she made just enough mistakes for Uncle Hamish to believe he’d won fair and square, her lips twitching affectionately when she discarded an ace and his mustache bristled with satisfaction. He was so dear, and she so grateful that he supported her decision, despite his natural concern and what were sure to be endless recriminations from his wife.

As soon as the game was over and tea was served, Flora excused herself and slipped outside. The rain had stopped and the sky was surprisingly clear. The stars glimmered like the flickering flames in a Christmas procession seen from afar. Were these the same stars Gavin gazed at from his trench, she wondered, sitting on the damp terrace despite Tante’s admonitions about catching a chill, her knees hugged under her chin.

The pale satin of her evening gown cascaded down the stone steps like a waterfall as she searched the gleaming stars, their sparkle replaced by Gavin’s twinkling blue eyes and possessive smile. She sighed and recalled each precious moment, each tender endearment and the treasured instant when his lips had finally touched hers. Before leaving, he had raised her fingers to his lips, kissing them ever so softly before whispering the question to which he already knew the answer. She smiled and bit her lip. How could he possibly have doubted? Of course she would wait for him. A lifetime, if need be.

Yet he never wrote. Never communicated directly except for the occasional scribble at the bottom of a page, sending his love and a hug. It was always Angus, the younger twin, who kept her abreast of their life in the trenches, sharing anecdotes, some so tragic they were hard to believe, others oddly humorous despite the circumstances.

Now, at last, it was her turn to experience these things.

She rose slowly and wandered back into the house, gazing affectionately at Tante’s stiff French furniture, the paintings and the delicate porcelain on the shelves, realizing how much it all meant to her.

Midfield and Strathaird had been home to her since she was barely four, when the family had taken her in as a surrogate daughter and sister after her parents’ death. It seemed a lifetime ago. But then, so did the boys’ departure to the front.

She heaved another sigh, feeling worldly-wise and much older than her years. The last few months spent at the hospital had been a shock at first, a revelation. The prim, innocent young girl who had entered its portals with no more knowledge of male anatomy than a nun was now a different person. She smoothed the faded brocade of her favorite cushion, glad that women were taking on new functions, becoming vital to the country’s economy, and learning much about themselves and their capabilities. That was about the only positive aspect of this dreadful war. All at once she remembered Tante’s veiled remarks at dinner and grinned, wondering if her aunt had the slightest idea of the tasks Flora performed each day—washing the men, dressing their wounds, emptying their bedpans.

At the drawing-room door she paused, smiling at Millie, Gavin’s spaniel. The dog wagged her tail patiently, hoping to be allowed into the hall. “Just a minute, Millie,” she said, her eye catching a photograph in a silver frame. It had been taken at Chateau de la Vallière, her cousins’ home in Limoges, during that last, wonderful summer of 1913.

She picked up the picture, tears welling suddenly. There was dear Eugène, serene as always, and his baby sister Geneviève. René, their younger brother, was slouching behind him and sulking. Uncle Eustace, dressed in a white suit and panama hat, leaned on a walking stick behind his sister’s deck chair, while in the foreground were Gavin, Angus and herself, sitting on the grass, their arms entwined. The merry trio—or rather, Gavin and his two faithful followers. What a beautiful day it had been. They had laughed and played, oblivious of what life had in store for them. She replaced the picture with damp eyes, wondering when the friendly banter she engaged in with Gavin had transformed into an embarrassed awareness that left her dizzy, her heart racing whenever he was around. Perhaps it had been that very afternoon. But it was not until last year, when he had returned for a short week’s leave, that she knew she was in love.

She leaned against the door, staring into space, recalling that thrilling moment when he’d walked in and their eyes had met and clung. Oh, what heaven it had been. Gavin, so tall and mature in his well-worn uniform. The white and purple ribbon of his M.C., the Military Cross won for bravery at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, was worn with casual nonchalance, although he was the youngest man to have received it yet. For days they had walked, talked and laughed, each too shy or too young to make the first move, yet so aware of one another it hurt.

She wrinkled her nose and stared at the picture once more. If she’d known half of what she knew now, she’d have given herself to him without a second thought, she realized, shocked at her own depravity. But there might never be another chance, unless…perhaps she would be blessed, and one day he would be brought in to her section of the field hospital. Not with a bad wound, of course, but just enough for him not to return to the front and for her to take care of him.

Tante’s singsong voice calling from upstairs interrupted her daydreams. She let Millie into the hall, regretting now that all she’d allowed Gavin was one chaste kiss. The thought of his lips on hers made her shiver, and she ran quickly up the stairs and along the corridor to her room. If only she was at Strathaird, she wished. There she had her favorite spot, among the worn chintz cushions of the window seat in the upstairs sitting room, where she would curl up and dream, gazing out over the lawn to the cliff and the churning sea below. Oh, how she missed it. The family fondly called the room “Flora’s dreamery,” for it was there she spun her yarns, meditated, daydreamed and saw things others didn’t, and where everyone always knew they could find her.

But tonight she had to content herself with having achieved her objective. At least now she would be close to Gavin, and truly serving her country. Finally she would be a part of this war to end all wars that would mark their lives forever.

2

Arras, France 1917

“‘If you were the only girl in the world,”’ an out-of-tune voice warbled.

“Gawd, you’ve got a bloody awful voice, mate.”

“Says who?”

“Says I. We should stick you out in no-man’s-land and let Franz ’ear you. ’E’d be off ’ome in an ’eartbeat, ’e would.”

Laughter ran the length of the trench, and banter flew as the men moved, ankle-deep in mud, trying desperately to keep their spirits up while they repaired the traverses, piling sandbags near the entrance to secure it before the next rainfall. Those taking a break sat smoking wherever they could find a dry spot, wrapped in their greatcoats, exchanging jokes. Lieutenant Angus MacLeod, of the Fifty-first Scottish Highlanders, leaned over and offered his brother a light.

“Thanks.” Gavin shielded it with his palm, took a long drag and surveyed the men, wondering how long it would be before they finally made an advance into the massive defenses, through the endless stretches of mud and barbed wire that separated them from the enemy. There was something big stirring, he was certain, for powerful artillery had been moved in to back them up. He felt sure General Harper’s orders would be imminent. Smoking, Gavin silently calculated their chances of success and reckoned they were slim. The German offensive was gruesome. “I hope things will be better than at Ypres,” he murmured to himself. There, the Guards, the Fifteenth Scottish, the Sixteenth Irish and several other assault divisions had fought themselves out from August through September in what was known as the battle of the mud at Passchendaele.

“It’s one of my last, so smoke it slowly,” Angus remarked, referring to the cigarette.

Gavin grinned affectionately, watching the thin ribbon of smoke rise above the damp earth of their burrow, and listened to the sound of the enemy artillery becoming uncomfortably close, noting the occasional flash of flares. Too damn close, he realized. Eyeing Angus, he decided not to share his misgivings with his brother. Although they were fraternal twins, their personalities were as different as their looks. Angus hated it all. They never talked about the war much unless they could help it.

“God, I wish this were all over,” Angus remarked gloomily.

“I don’t know, it has its moments.” Gavin took another long drag, enjoying the scent of the Will’s tobacco, which was a dash sight better than the never-ending stench of gangrene and death. “This may be the one exciting thing that will ever happen in our lives. Once we’re home, Papa will expect us to follow in his footsteps, enter the wretched coal business and lead life exactly as he did.”

“Ha!” Angus shook his red head. “Trust you to consider this mess an adventure.”

“What makes you think life will be the same as it used to be?” Jonathan Parker, a young medical student from Cambridge, asked, swallowing tea from his tin mug. “I don’t think anything can ever be the same. For one thing, people aren’t going to be as complacent as they were. And God knows what will happen if we lose.”

“Lose, be damned,” Gavin replied. “We can’t.”

“If the doughboys don’t take a hand in it soon, we will, old chap. Look at us, for Christ’s sake! Three bloody years and we’ve only a couple of miles gained and few hundred thousand dead to show for it. That’s not counting the wounded,” Jonathan added with a bitter laugh.

“You’re right.” Angus nodded, pulled his greatcoat closer. “Who knows how long it may go on?” he added dismally.

With the sound of a courier arriving at the entrance of the trench, every head turned in unison. The men stopped smoking and those working laid down their picks and shovels, silently praying his name would be called. Letters from home were what kept a man sane. As names were called out and letters passed down the line, those who received nothing got back to work, masking their disappointment.

“Angus MacLeod.” Angus leaned forward as the letter was passed down.

“Who’s it from?” Gavin asked, stubbing out the precious cigarette casually, knowing the girls at Paris Plage could get him more.

“Flora. It’s from Flora,” Angus replied, blushing, his hands trembling as he slit open the envelope.

For a second, the sweet softness of her gray eyes and her mysterious smile replaced the mud, the wet and growing rumble of enemy fire. And for a moment, Gavin wished he’d written, but it just didn’t come naturally. He could say the words, and felt them deep inside. But write them? No. He didn’t like writing letters. He hadn’t even written that infamous “goodbye” letter, the one you left for after you were killed. Not him. Something told him it wasn’t a good omen. He shrugged, eyeing Angus impatiently as he read the letter, wishing she’d addressed it to him.

“I think you’ve got a crush on her,” he teased, dying to hear what she had to say.

“You know she only has eyes for you.” Angus scanned the lines avidly, then frowned.

“Well,” Gavin prodded, “what does she say?” Again he wished that she’d write to him. But then, she had before and he’d never taken the trouble to reply. Gavin shrugged. Flora knew he loved her. She would wait. She understood him as no one else ever could. She was his. He wished he’d kissed her again that last time they’d been together. But he couldn’t. If he had, things would have gotten out of hand. She was so young, so lovely, so innocent…Biting back his feelings, he nagged his brother again. “Well, come on. What’s she got to say for herself?”

“She’s coming out,” Angus replied in a flat voice.

“What do you mean?” Gavin’s head flew up.

“She’s asked to be posted overseas. She’s being sent here to France.” He glanced at the date of the postmark. “In fact, she’s probably here by now. This letter is more than a month old.”

“Good God. But why would she do that? There’s no reason for her to. Surely Papa could have intervened.”

“She says here that Father backed her up. She wants to do this, Gavin,” he added quietly, handing him the letter. “She’s made a choice.”

Gavin scanned the lines. Feeling powerless, he kicked a piece of stray traverse angrily, afraid for the first time. He knew how to take care of himself, damn it, but the thought of Flora in danger, without him to take care of her, had him swearing. Why hadn’t she stayed at home, where he knew she’d be safe? “You’re right about this damned war,” he exclaimed suddenly. “It’s time we got on with our lives. Do you think she’ll be posted near us?”

“She’ll probably be sent to Etaples,” Angus replied. “That’s where most of the V.A.D.s get sent when they first come out.”

“At least that’s not in the middle of the fighting. Still, I don’t like it.” Gavin looked up as the sound of shellfire intensified. He glanced at his brother, away in a world of his own, then stared back at the letter. His name had been pointedly avoided. She was angry he hadn’t written, he supposed. Well, he’d explain later, clear things up.

“Perhaps we’ll be able to see her,” Angus said dreamily.

“Maybe. If we live long enough,” Gavin answered, squinting upward.

“Oh, you will,” Angus laughed, his face alight with sudden admiration. “You’re like a cat, always falling back on your feet. We made it out of the Somme last year thanks to you.”

“Rubbish.” Gavin handed him back the letter then checked his rifle. “We all did our part. Imagine our little Flora at the front, though. It seems so strange. And I don’t like it one bit.”

“Not so little anymore, and from what I gather between the lines very much in love with you.” Angus gave him a fixed smile.

“I don’t know.” Gavin cocked his ear and tried to identify the exact direction of the increase in shellfire.

“Of course you do. You always have. You’ve only had eyes for one another for as long as I can remember,” Angus replied a touch bitterly.

Gavin gave him a surprised glance. “Jealous?”

“Of you two? Of course not.” Angus shook his head. “You’re meant for one another. I never stood a chance. She’s very fond of me. As a cousin and friend, that is.”

“Well, if anything happens to me, I suppose you’d better take care of her for me. Can’t have her going to some stranger.” Gavin spoke with a flippancy he was far from feeling, and scanned the trench once more. Deciding where to position his men, he ducked as the firing grew suddenly louder and a flare nearly grazed his head. “What in hell’s name’s going on? I know we’re in the middle of a bloody offensive, but it’s too damn close for comfort and I’ve not received any direct orders from H.Q. I hope the telephone lines aren’t down.” He raised his head aboveground.

“Don’t, you fool, you’ll get yourself killed.” Parker yanked him back.

“We need to know what’s happening.” Gavin jumped back down into the squelching mud and took charge. “Summers, stand to.” He ordered. “Marshall, keep the end bay covered.” He shouted orders as the noise increased and the men hastened as best they could, taking up their positions.

Then an eerie hum approached. Too late he realized what was about to happen. “Move,” he shouted, pushing Angus down into the mud in the split second before the explosion. Then pain tore through him. His body jerked up before it was thrown into a tangled mass of torn limbs, ripped flesh and horrifying screams.

For a while, he thought he was dead. Then, gradually, consciousness returned and he heard cries, smelled the bitter, acrid smoke. He tried to move but pain shot through his hip and thigh; he tried to open his eyes but they stung. Everything was hazy. He felt about him in a daze, all at once aware that the soft, wet substance he was touching must be flesh, and choked, as horror, gas and blood filled his lungs and he tried vainly to move.

Little by little he extracted his left hand from the sticky warmth below, gripped by nausea when he realized he was lying on Jonathan Parker’s dead body. He gasped, trying to catch his breath. Trying to think. He was alive. He had to stay alive. But where was Angus? Making a superhuman effort, he heaved the mangled pile of blood-soaked remains that lay across him, hearing the sound they made as they sank into the mud. The effort left him exhausted. But he focused now, and the rush of relief when he saw Angus staring down at him, apparently unharmed, was overwhelming. Thank God. He tried desperately to speak, but his lips wouldn’t move. To motion, but his arm wouldn’t budge.

Angus stared at him, expression detached. Gavin shouted but no sound emerged. Couldn’t Angus see him, damn it? He closed his eyes against a whiff of gas. When he was able to open them once more, Angus’s face still loomed impassively over him, an expressionless mask. Why didn’t he pull him out of here instead of just standing there? “Angus,” his mind screamed. “Help me, for Christ’s sake!”

But Angus made no gesture, no motion. Instead, he crouched beside him, wearing the cold, half-amused, disinterested gaze of a spectator. Desperately, Gavin reached his left arm toward his brother in a frantic effort, daggers searing through his hip and upper body as he grasped the gold chain and cross swinging from his twin’s neck, clutching it.

But Angus made no move and the chain gave way. Gavin reeled back, collapsing once more in the mire of blood, mud and misery. As his head sank into Jonathan Parker’s open guts and everything went black, his last conscious image was of Angus, watching calmly as he sank into oblivion.

3

Etaples, France, 1917

“Nurse, we need to vacate the facility immediately. There’s a new convoy coming in from the front lines. They’re bringing in the wounded as we speak.”

“Yes, Sister.” Flora hurried around the ward, which she and Ana, another V.A.D., ran with virtually no assistance, and helped the patients who could walk to other wards. Once they’d all been shifted to the next building, Flora hurried back to prepare beds and blankets for the new arrivals. As she tucked in the last sheet, she heard the ambulances drawing up and sighed, realizing it would be another long night. Every spare hand was needed and getting to the wounds before they festered and required amputation had become a grilling challenge.

She dumped the dirty laundry in a corner and prepared for the onslaught, forcing herself to stay calm, pushing away the fear that each new batch of arrivals brought. Inevitably she searched each incoming stretcher for his face, praying it wouldn’t be there. Flora sighed again. She’d had less news in the two months she’d been here than all the time back home.

She pulled herself together as the wounded began pouring in, and the usual frenzy of dressing wounds, injecting morphine and preparing the dying began. There were plenty of those today, she realized, horrified.

The doctor approached, face exhausted and eyes bloodshot, his white coat splattered with muted bloodstains that no amount of washing erased. He looked at the wound. “Better to put a bullet through the poor bugger,” he muttered angrily before setting to work. The priest and the chaplain stood nearby; they had long since stopped bothering about denominations, instead simply murmuring prayers in a desperate effort to bring solace to those last remaining moments, leaning close to catch final messages whispered from barely moving lips.

Flora worked nonstop. There would be countless letters to write to the soldiers’ families, she thought sadly. It was the only tribute she could pay to the young men who’d died so valiantly in her arms. At least she could give their loved ones the treasure of their last words. When there were none, she took it upon herself to invent them, sure that what mattered most was that a parent or a wife be given something to cling to.

“Pass the morphine, Nurse. I’m afraid we’ll have to amputate,” the doctor said above the moans and agitation. Flora glanced at him, his young face prematurely lined, marked by three years of battling disease, death and devastation.

She handed him the bottle as a young orderly came up to her. “Nurse, we have a bad case of shell shock. Where should we put him?”

“Oh my goodness. Is he wounded?” she asked distractedly, preparing for the operation that was about to take place.

“No.”

“Then put him in number ten and I’ll get to him whenever I can. I’m afraid I can’t do anything about it at the moment.” He nodded and left, and Flora prepared the patient for amputation, trying to overcome the nauseous smell and increasing heat in the ward. The hospital back home had seemed bad, but here life was hell. There was none of the priggish, ordered behavior of regular hospital life, with the petty rules and hierarchies of the matron. All of that was forgotten in a common effort to save as many lives as they could.