The Tower: Part Four

… of course …

The second symbol represented the Citadel and the disease had started there and was now spreading. The next part of the prophecy was coming to pass.

The musak cut out.

‘Liv?’

‘Arkadian.’ More noise in the background, like he was on a street full of children. ‘Are you OK? I just saw the news about the outbreak.’

‘It’s chaos here. People are scared. I’m scared. We’re evacuating the children from the city. Where are you?’

She looked out of the window at the distant movement of people working on the hill as they dug the new grave. ‘Still in the desert,’ she said. ‘We found it.’

‘I know. Gabriel told me.’

Liv felt the world shift. ‘Gabriel! You spoke to him?’

‘Yes.’ Another pause filled with the babble of children. ‘Just before he was taken into the Citadel.’

Liv felt like all the air had been sucked from the room.

‘He was sick, Liv, he had the virus – but he was not as sick as the others.’ She gripped the sides of her chair and reminded herself to breathe. ‘Most of them go mad when the disease takes them, but not Gabriel. He rode all the way back here because he knew he had it. He didn’t want it to spread. It was Gabriel who insisted the disease be contained inside the Citadel. He wanted to take it back where it came from. He wanted to beat it. And if anyone can do it, it’s him.’

Liv tried to speak but couldn’t. In her ear she could hear Arkadian still speaking but she didn’t hear his words. Her eyes dropped down to the red stained piece of paper and scanned the second line again, a terrible new meaning emerging from it in the light of Arkadian’s revelation.

Disease

Citadel

A knight on horseback – Gabriel

She remembered the words on the note he had left her, telling her that leaving her was the hardest thing he had ever done. And now she knew why. He must have known he was infected. He’d known that and had still ridden all the way back to the Citadel, just to protect her.

She looked at the remaining symbols on the second line of the prophecy, hoping she might find something hopeful in them, but all she saw was more misery.

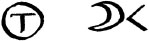

She knew what it meant now. The T was her, the circle confinement and the moon and chevron told her how long it would all last.

Nine moons – Eight months.

She clicked on the video clip embedded in the news article. It had been filmed from a news helicopter at night so the quality wasn’t great. A bright searchlight picked out a procession of patients strapped to stretchers and being carried to the mountain. She studied the faces, all looking straight up into the sky. Even through the grainy images she could see the masks of pain their faces had become. Tears started to run down her cheeks then the light swung away, settling again on the last stretcher to emerge from the church. She hit the space bar to pause it just as Gabriel looked straight up at the camera. It was like he was staring straight at her, like he was saying goodbye. Her love. Her life – being carried away on a stretcher, and into the heart of the hateful mountain.

60

Franklin finished his cigarette and flicked it out of the window. ‘You ever been married, Shepherd?’

‘No.’

‘And you don’t have kids, do you?’

‘No, I don’t.’

They were on the outskirts of the town now with widely spaced houses emerging from the trees, a general store with lights burning in the windows and a sign outside saying St Matthews Piggly Wiggly. There was a gas station on the other side of the road, also open for business. Franklin drove past them both, all pretence of getting food and gas now abandoned.

‘When you have kids, everything changes. It’s like taking your heart out of your chest and watching it walk around. You’d do anything for them, anything at all. And if you have a daughter,’ he shook his head, ‘well that’s a whole other ball game. The world suddenly seems ten times more dangerous than it did before, a hundred times, and she is so vulnerable and fragile in it.’

He slowed down and took a right into a one-lane street lined with neat, single-storey houses with wooden porches and brick chimneys, their front lawns all blanketed in white.

‘So you work your ass off to put a roof over her head, give her a good life, protect her from all the crap that you know is out there, the stuff that you see every day. Everything you do takes on new meaning, every bad guy I ever put away was dedicated in some way to my daughter. I did it for her, to make the world a safer place for her, and for her mother.’

He took another left onto a road lined with bigger houses, some with four-car drives.

‘And you try so hard to shut off the darkness you have to deal with but it’s always there, like a stain. So you keep it from your kids by keeping yourself from them, because, in a way, you are the thing you want to protect them from.’

He brought the car to a halt outside a house with a long sloping roof like a ski jump. Franklin fixed his eyes on it and killed the engine.

‘Then one day you realize you don’t know who they are any more, either of them. You’ve spent so long working to give your family a better life that you’re no longer a part of it. You’ve become a stranger in your own home. You can’t talk to them, you can’t understand them, you’re only aware of the distance between you where once there was no gap at all.’ He looked away and Shepherd wondered if the tough old bastard was actually crying.

‘I’m sorry I dragged you all the way out here,’ Franklin said, turning back and looking him square in the eye. ‘I kind of convinced myself it was all about the investigation but in the end it looks like it’s all about me.’ He nodded at the sideways house. ‘And you were right about the homing instinct.’

‘You don’t have to explain it.’

Franklin turned to him. ‘You said you didn’t have a home.’

‘I don’t, at least not like this. But home means different things to different people.’ He took a breath ready to tell him … about Melisa, about his missing two years, even about how he was using the MPD files to try and find her again. But just then the door of the house opened and a girl of about twenty stepped out.

Cold air flooded in as Franklin got out of the car. Shepherd watched him walk up the drive towards her, like he was being pulled by an invisible thread. He stopped a few feet short of her and they stared at each other. Then she stepped forward and wrapped her slender arms round his neck and buried her face in his chest. Behind them another woman, an older version of the girl, stepped onto the porch and stared at them for a moment. Then she too came forward, a smile breaking on her face like a sunrise, and Shepherd looked away, feeling uncomfortable about sharing such a private moment even from a distance.

He stared down the street at the other houses. Some were empty and dark, the drives showing the fading tyre tracks of cars no longer there. Other houses glowed, their festive decorations lighting up the snow like Christmas cards.

Witnessing the power of the homing instinct and its effect even on someone like Franklin made him realize that the pull to find Melisa and the reckless things it was making him do was simply the same thing working in him.

The rap of a knuckle on his window snapped him back to the present.

Franklin was standing outside the car. Shepherd got out, snow crunching beneath his shoes and cold air on his skin.

‘You want to come in, grab some lunch?’

Shepherd looked over at the porch where the two women were standing watching them. ‘I don’t think so. I’d just be in the way.’

Franklin nodded. ‘Listen,’ he said. ‘When I drove here I thought … well, I don’t know what I thought, but now I’m here I don’t think I can leave again, not for a while at least.’

‘It’s OK, I understand. I’ll go on to Cherokee alone, see if I can find Douglas’s place. It’s probably a waste of time anyway, I only ever went there once.’

‘Don’t do anything stupid,’ Franklin said, his brow creasing with the difficulty of what he was doing. ‘And if you do find him, don’t approach him on your own. Call me first, OK?’

‘He’s my old teacher – what’s he going to do, give me a tough assignment?’

‘He’s a wanted terrorist who nearly got you killed in an explosion this morning. Don’t forget that.’

‘OK, if I find him I’ll call – I promise. Now get inside that house, Agent Franklin, and spend some time with your family.’

‘Ben.’

‘What?’

‘Name’s Ben, short for Benjamin: it’s not my bureau name, it’s my real one. My old man won a hundred-dollar bill for calling me it when I was born, asshole that he was. He’d probably have called me George if our name had been Washington, just to win a dollar.’

‘It’s a fine name, Ben. You wear it well.’ Shepherd held out his hand.

And Franklin shook it.

61

Rosie Andrews crunched through the snow towards the ATM. It was out of service, just like all the others. Nothing was working. Everything was falling apart. She felt tears bubbling up through her growing panic. She had about fifteen dollars in her purse, two maxed-out credit cards, a quarter of a tank of gas and at least a three-hour journey ahead of her. The gas would get her maybe fifty miles out of Asheville, about a third of the way down to her mom’s in Atlanta, maybe even less the way her station wagon was loaded up.

From somewhere across the parking lot she heard glass shatter followed by a roar of voices that made the hairs bristle on the back of her neck. She turned and hurried back to where she had left the car, parked behind a dumpster on the far side of the lot, away from the large angry-looking crowd she had seen outside the big Petro Express when she had driven in. It all added to the sick feeling that had been growing inside her that made her feel something was terribly wrong. The crowd had been arguing with security staff who were allowing only a few people in at a time to control numbers.

There was another crash and the roar got louder.

Sounded like the security guys had lost the argument.

The noise frightened her. It was the sound of violence and chaos and it made her feel small and vulnerable. She just wanted to get some money and get out of here. She just wanted to get home.

She rounded the edge of the dumpster, fretting in her pocket for her keys, and saw the man leaning down by the side of the car, his face pressed against the rear window. Rosie felt blood singing in her ears and her vision started to tunnel.

‘What are you … you get away from there.’

The man looked up but didn’t move – he just kept looking at her in a way she didn’t like.

Another crash of glass behind her. Another roar.

She pulled her hand from her coat and pointed it at him. ‘You step away from the car, you hear me?’

The man looked down and registered the gun she was holding, but still he didn’t move.

‘Is this man bothering you, sweetie?’

The voice made her jump. Rosie’s head jerked round to discover a birdlike woman standing next to her, so small she was almost like a child. She was looking up at her, her blue eyes cold against the snow. In her peripheral vision she saw movement, the man moving forward, using the distraction to close the gap between them.

She stepped backwards, slipping on the ice a little but holding the gun steady in a good grip like she’d practised on the range. She was going to shoot him. If he took one step closer she would fire without hesitation. She had often wondered if she would be able to do it if she found herself in a situation like this but now there was no question in her mind that she could. It was a nature thing. A primal instinct to protect what was yours. She took another step back, opened her mouth to warn the man one last time, then an object banged against her side.

The movement was so fast she didn’t even feel the pain until the blade was sliding back out from between her ribs, so sharp and sudden that it snatched the breath from her mouth as quickly as the man took the gun from her hand.

She felt confused, like everything was happening to someone else and she was just watching. Warmth spread out from the burning pain in her side and she looked down at the red bloom spreading over the white of her coat.

Blood. Her blood.

The sight of it shocked some sense back into her and she took a ragged breath ready to scream but a strong hand clamped over her mouth and dragged her further back into the shadows behind the dumpster.

Carrie watched Eli holding the woman tightly, making sure her blood spilled away from him and onto the snow and not his boots. When her body went limp he laid her gently on the ground and patted down her pockets until he found the keys.

‘Shame,’ he said, standing up and moving over to the car.

‘Just bad timing I guess,’ Carrie said, inspecting the blade of her knife and wiping it with a handful of snow.

‘I didn’t mean her.’ Eli pressed the button on the keyfob and the car thunked as the central locking disengaged. He opened the back door and nodded towards the interior. ‘I meant her.’

The backseat was crammed with boxes of groceries, rolls of bedding and a couple of laundry bags overflowing with baby-girl clothes. The owner of the clothes was wrapped up tight in a quilted snowsuit and strapped into a kiddie car-seat, asleep, a single strand of blonde hair escaping from beneath a hand-knitted woollen hat.

Carrie moved over and watched the tiny chest rise and fall, eyes moving beneath the lids as she dreamed her little-girl dreams. Carrie’s hand found Eli’s and she wrapped all of her fingers round one of his but he pulled away, reaching across the tiny sleeping form to pick up a pillow from the pile of bedding. ‘Look away, honey,’ he said, ‘you don’t need to see this.’

She opened her mouth to speak but then thought better of it. Eli was right. This was no world for a little girl to go through without a mother by her side, she knew that much herself, and this little poppet was sweet and innocent enough to pass straight into heaven, no questions asked. Eli was doing her a favour, a great favour, by doing this thing for her. He was so kind and strong where it really counted, in the heart – and that was why she loved him.

‘Suffer the little children to come unto me,’ she said, reaching out to gently tuck the lock of hair back under the woollen hat. Then she kissed Eli on the cheek and turned away.

V

And the kings of the earth, and the great men, and the rich men, and the chief captains and the mighty men … hid themselves.

For the great day of His wrath is come; and who shall be able to stand?

Revelation 6:15–17

62

Gabriel drifted in and out of consciousness. At times he raved, howling and bucking against the bindings, other times he was calm enough to converse with the doctors for minutes at a time, giving them insights into how the infection felt, like a drowning man describing the experience in snatched breaths to someone in a nearby boat before another wave engulfed him and dragged him back under. He fought, he screamed, he scratched and he cried – but he did not die.

Athanasius watched it all from a seat by the bed. He was there at night when the flicker of candles and flambeaux cast ghoulish light across Gabriel’s face, and in the day when the sunlight streamed through the huge rose window, dappling the damned with colour. The beds surrounding them emptied and filled, over and over as the tide of sickness ebbed and flowed, and more and more people entered the mountain. First it was those who had rested in quarantine in the Seminary. Then new faces began appearing, steady in number, their brief stay always numbering a day or two at most and always following the same journey: carried in writhing and screaming, carried out silent and still to the centre of the mountain and the firestone where the pyre always burned.

Then, on the second day of the fourth week after the Citadel had opened its doors to the sick, Gabriel opened his eyes and they stayed open. It was the middle of the afternoon after the doctors had finished their rounds and Athanasius was away attending to the organization of what was left of his flock. He lay there, staring up at the soot-blackened stalactites high above him, listening to the drugged moans of the infected and the creak of their bindings as their bodies clenched and twisted all around him. He lay there a long time, bracing himself for the moment when the fever would drag him back down again, as it always had before. But this time it did not.

‘Hello,’ he called out, his voice raw and unfamiliar. Murmurings rose from the beds surrounding him, the sick roused from their drugged slumber.

‘HELLO,’ he called again, loud enough to hurt his throat and bring footsteps hurrying. A face appeared above his bed, brow furrowed, eyes ringed with the shadows of deep fatigue. Gabriel didn’t know him but he recognized the contamination suit he was wearing – and he also noticed the loaded syringe.

‘No,’ he said. ‘You don’t need to do that. I feel better.’

It was as if the doctor hadn’t heard him, his sleep-starved brain running through the well-worn routines of patient sedation. Gabriel felt the cold alcohol swipe of an antiseptic swab on his arm. He tried to twist away but the bindings held him fast.

‘WAKE UP!’ he shouted, as much to the doctor as to those surrounding him. ‘WAKE UP!’

The effect was instant, the faint murmurings erupting into howls as the sleeping sick were shocked into wailing wakefulness. The doctor looked up at the chaos now surrounding him, every patient around him now bucking and thrashing against their bindings as they howled in torment. He looked back down at Gabriel, his eyes shining with annoyance at the trouble he’d caused, he held up the syringe and readied the shot.

‘What are you doing?’ Gabriel growled, his throat raw from his shouting. ‘I do not need sedating. See to the others first. Their need is clearly greater.’

The doctor hesitated, looked like he was still going to spike him, then a shadow passed over Gabriel’s face and he glanced across to see the smooth-headed figure of a monk standing on the other side of his bed. ‘It’s OK,’ Athanasius said to the doctor, ‘I shall sit with him. You see to these other poor souls.’

The doctor blinked as though a spell had been broken, then turned away to start dealing with the others.

Athanasius pulled the stool out from beneath Gabriel’s bed and settled on it. His eyes were bloodshot and sunken and he smelled of wood smoke. Gabriel breathed it in, relishing the smell. It was the first time in a long while he had smelt anything other than the strange and permanent odour of oranges. And there was something else. He was cold and his sweat-soaked bindings felt wet and unpleasant against his skin.

‘The fever,’ he whispered in realization of what this meant. ‘It’s gone.’

Athanasius laid a warm hand on Gabriel’s forehead and straightened in his chair. ‘Thank God,’ he said.

Another figure appeared by the bed and held a thermometer in his ear. It beeped and he checked the reading. He reset it and did it again.

‘Ninety-eight point six,’ he said, the hint of a smile on his weary face. ‘You’re probably a few points cooler than I am.’

‘Dr Kaplan, allow me to introduce Gabriel Mann,’ Athanasius said.

Gabriel nodded a greeting. ‘I’d shake your hand but someone tied me to this bed.’ Kaplan smiled again. ‘Tell me. Did the quarantine work. Has the disease been contained?’

He knew the answer before either of them spoke. He heard it in the pause and saw it in the flick of their eyes as they looked away from him.

‘There have been new cases,’ the doctor replied, ‘ones that have originated beyond the line of the original quarantine in the metropolitan districts of the city. We have continued to remove the infected and quarantine those at risk but we have so far been unable to contain it. As of last week a state of martial law has been in place in the greater city of Ruin to try and prevent the further spread of the disease. The army and the police have set up roadblocks on the road leading out of the mountains. No one is allowed in, no one is allowed out. But we have made significant steps since moving here. And you may hold the key to all of our salvation. No one has fought the disease as long as you have, and no one has recovered – until now. But it’s still early days and you may yet relapse.’

He looked up at Athanasius. ‘We need to move him somewhere isolated.’

‘No,’ Gabriel said, ‘I’ll stay here, I don’t need special treatment.’

‘You don’t understand,’ Kaplan said. ‘You need to be in isolation, not just for your own comfort but for the safety of others. Your body may have defeated the infection but there is another possibility. Sometimes the body’s natural defences do not entirely vanquish a hostile agent. Sometimes a kind of truce is arrived at where the disease is kept in check and the symptoms disappear. If this has happened then you may now be an asymptomatic carrier of the disease, immune yourself but deadly to anyone who comes into contact with you. There is also the possibility that the infection has mutated inside you and formed a new strain, one that your body is immune to because it helped create it but one that is every bit as deadly as the first strain – maybe even more so.’

Gabriel stared up at him. He hadn’t given conscious thought to his hopes until now. The one thing that had kept him going throughout his suffering and delirium was the thought of Liv. She was the one he had fought death for. He had left her in the desert in the hope that he carried the disease away with him. He had travelled all the way back to Ruin in the hope it may not have spread. He had insisted on being taken inside the Citadel where the blight had first come from and then refused to die in the hope that he might finally be reunited with her. Now he was told that he must stay here, isolated even within this place of isolation. There were many words to describe the pain that filled him, but only one that completely summed up the way he felt.

Cursed.

Athanasius read the pain on his face. ‘I know a place where we can move him,’ he said.

63

Following her conversation with Arkadian, Liv scoured every news site and story relating to the contagion in Ruin until the laptop’s battery ran out.

She sat alone for a while in the sweltering heat of the building feeling like she had just experienced a bereavement. She closed her eyes and remembered the last time she and Gabriel had been alone together, sheltering from the dust storm in the cave out in the desert. She had thought then that her life was slipping away, that the Sacrament she carried inside her would die without finding its way back to the home it had lost, and drag her down to death with it. She had clung to him then like she was clinging to life. She remembered the feel of him, the salty taste of his skin as they had kissed when they had given themselves to the moment and each other in case it turned out to be the only night they ever had.