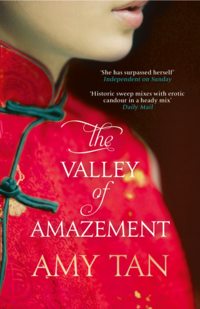

The Valley of Amazement

The table was set with savory, sweet, and spicy dishes—bamboo shoots and honeyed lotus root, pickled radishes, and smoked fish—so many tasty things. I was hungry but ate sparingly and with the delicate manners I had seen courtesans use at Hidden Jade Path. I wanted to show her she had nothing to teach me. I picked up a tiny peanut with my ivory chopsticks, put it to my lips and set it on my tongue, as if it were a pearl being placed on a brocade pillow.

“Your upbringing shows,” the old bustard said. “A year from now, when you make your debut, you can charm men to near insanity. What do you say to that?”

“Thank you, Mother Ma.”

“You see,” she said to the others with a pleased smile. “Now she obeys.” When Mother Ma picked up her chopsticks, I had a closer look at her fingers. They resembled rotting bananas. I watched her peck at the remaining bits of food on her plate. The sneaky courtesan Petal stood up and quickly served the madam more bamboo shoots and fish, but did not touch the last of the honeyed lotus root. She waited until Spring Bud helped herself to the last big piece, then said in a chiding tone, “Give that to Mother. You know how much she loves sweets.” She made a show of shoving her own lotus root pieces onto Madam Ma’s plate. The madam praised Petal for treating her like a true mother. Spring Bud showed no expression and looked at no one. Magic Gourd looked sideways at me and whispered, “She’s furious.”

When Mother Ma rose from her chair, she wobbled, and Petal ran to steady her. The madam crossly swatted her away with her fan. “I’m not a feeble old woman. It’s just my feet. These shoes are too tight. Ask the shoemaker to come.” She lifted her skirt. Her ankles were gray and swollen. I guessed her feet under her bindings were even worse.

As soon as the madam left the table, Camellia said to Magic Gourd in an overly polite tone, “My Peer, I cannot help saying that the peach color of your new jacket flatters your coloring. A new client would think you’re at least ten years younger.”

Magic Gourd cursed her. Camellia smirked and walked away.

“We tease each other all the time like that,” Magic Gourd said. “I flatter her thin hair. She flatters my complexion. We laugh rather than cry about our age. The years go by.” I was tempted to tell Magic Gourd that the peach color did not flatter her at all. An older woman wearing a younger woman’s colors only looks as old as she is pretending not to be.

I followed Magic Gourd’s advice. I did what the madam expected. I performed the toady greetings, answered politely when she talked to me. I showed the rituals of respect to the flower sisters. How easy it was to be insincere. Early on, I received a few slaps whenever I had facial expressions that Mother Ma judged to be American. I did not know what they were until I felt the blows and she threatened to grind down any part of me that reminded her of foreigners. When I stared at her as she scolded me, she slapped me for that as well. I learned that the expression she wanted was cowering respect.

One morning, after I had been at the Hall of Tranquility for nearly a month, Magic Gourd told me that I would be moving into a new room in a few days. The old one was meant to humble me. It was a place to store old furniture. “You’ll have my boudoir,” she said. “It’s almost as nice as the one I had at Hidden Jade Path. I’m moving somewhere else.”

I knew what this meant. She was leaving for someplace worse. I would have no ally if she did. “We’ll share the room,” I said.

“How can I do my wooing when you’re in the room playing with dolls? Oh, don’t worry about me. I have a friend in the Japanese Concession. We’re renting a two-story shikumen and will run an opium flower house, the two of us, with no madam to take the profits and charge us for every little plate of food …”

She was going to lower herself to an ordinary prostitute. They would simply smoke a few pipes and then she would lie down and prop open her legs to men like Cracked Egg.

Magic Gourd frowned, knowing what I was thinking. “Don’t you dare pity me. I’m not ashamed. Why should I be?”

“It’s the Japanese Concession,” I said.

“What’s wrong with that?”

“They hate Chinese people there.”

“Who told you that?”

“My mother. That’s why she didn’t let Japanese customers into her house.”

“She didn’t allow them because she knew they’d take away the best business opportunities. If people hate them, it’s because they envy their success. But what does any of that matter to me? My friend told me they’re no worse than other foreigners, and they’re scared to death of the syphilitic pox. They inspect everyone, even at first-class houses. Can you imagine?”

Three days later, Magic Gourd was gone—but for only three hours. She returned and dropped a gift at my feet, which landed with a familiar soft thump. It was Carlotta. I instantly burst into tears and grabbed her, nearly crushing her in my hug.

“What? No thanks to me?” Magic Gourd said. I apologized and declared her a true friend, a kind heart, a secret immortal. “Enough, enough.”

“I’ll have to find some way to hide her,” I said.

“Ha! When Madam finds out I brought her here, I wouldn’t be surprised if she hangs red banners over the door and sets off a hundred rounds of firecrackers to welcome this goddess of war. Two nights ago, I let some rats loose in the old bustard’s room. Did you hear her shouts? One of the servants thought her room was on fire and ran to get the brigade. I pretended to be shocked when I heard the reason for her screams. I told her: ‘Too bad we don’t have a cat. Violet used to have one, a fierce little hunter, but the woman who’s now the madam at Hidden Jade Path won’t give her up.’ The old bustard sent me off immediately to tell Golden Dove that she paid for you and everything you own, including the cat.”

Golden Dove had been glad to relinquish the beast, Magic Gourd reported, and Little Ocean cried copious tears, proof she had treated Carlotta well. But Magic Gourd brought back more than Carlotta. She had news about Fairweather and my mother.

“He had a gambling habit, a fondness for opium, and a mountain of debt. That was not surprising. He took money that people had invested in his companies and used it to gamble, thinking he could then make up for his previous business losses. As his debts piled up, he reported to his investors that the factory had suffered from a typhoon or fire, or that a warlord had taken over the factories. He always had an answer like that, and he sometimes used the same excuse for different companies. He did not know that the investor of one of his companies was a member of the Green Gang, and the investor of another was also with the Green Gang. They learned how many typhoons had happened in the last year. It is one thing to swindle a gangster and another to make fools of them. They were going to hang him upside down and dip his head in coals. But he told them he had a way to pay them back—by chasing away the American madam of Hidden Jade Path.

“Ai-ya. How can a woman so smart become so foolish? It is a weakness in many people—even the richest, the most powerful, and the most respected. They risk everything for the body’s desire and the belief they are the most special of all people on earth because a liar tells them so.

“Once your mother was gone, the Green Gang printed up a fake deed that said your mother had sold Hidden Jade Path to a man who was also a gang member. They recorded the deed with an authority in the International Settlement, one who was also part of the gang. What could Golden Dove do? She could not go to the American Consulate for him. She had no deed with her name on it because your mother was going to mail it after she reached San Francisco. One of the courtesans told Golden Dove that Puffy Cloud had bragged that she and Fairweather were now rich. Fairweather had exchanged the steamer tickets to San Francisco for two first-class steamer tickets to Hong Kong. They were going to present themselves as Shanghai socialites, who had come to Hong Kong to invest in new companies on behalf of Western movie stars!

“Golden Dove was so angry when she told me this. Oyo! I thought her eyes would explode—and they did, with tears. She said that a new gang with the Triad did not care about the standards of a first-class house. They own a syndicate with a dozen houses that provide high profits at low costs. There is no longer any leisurely wooing for our beauties, and no baubles, only money. The Cloud Beauties would have left, but the gangsters gave them extra sweet money to stay, and now they are caught in a trap of debt. The gangsters made Cracked Egg a common manservant, and now the customers who come are swaggering petty officials and the newly rich of insignificant businesses. These men are privy to the attentions of the same girls once courted only by those far more important. There is no quicker way to throw away the reputation of a house than to allow the underlings to share the same vaginas as their bosses. Water flows to the lowest ditch.”

“They have no right,” I said over and over again.

“Only Americans think they have rights,” Magic Gourd said. “What laws of heaven give you more rights and allow you to keep them? They are words on paper written by men who make them up and claim them. One day they can blow away, just like that.”

She took my hands. “Violet, I must tell you about pieces of paper that blew back and forth between here and San Francisco. Someone sent a letter to your mother claiming it was from the American Consulate. It said you had died in an accident—run over in the road or something. They included a death certificate stamped with seals. It had your real name on there, not the one Fairweather was going to give you. Your mother sent a cable to Golden Dove to ask if this was true. And Golden Dove had to decide whether to tell your mother the death certificate was fake, or to keep the beauties, you, and herself from being tortured, maimed, or even killed. There was really no choice.”

Magic Gourd removed a letter from her sleeve and I read it without breathing. It was from Mother. The letter rambled on about her feelings in getting the letter, her disbelief, her agony in waiting to hear from Golden Dove.

I’m tormented by the thought that Violet might have believed before she died that I had left her behind deliberately. To think those unhappy thoughts might have been her last!

I seethed. She chose to believe I was on board because she was eager to sail away to her new life with Teddy and Lu Shing. I asked Magic Gourd for paper so I could write a letter in return. I would tell Mother I wasn’t fooled by her lies and false grief. Magic Gourd told me no letter from me would ever leave Shanghai. No cable could be sent. The gangsters would make sure of that. That’s why the letter Golden Dove wrote to my mother had been the lies they told her to write.

I BECAME A different girl, a lost girl without a mother. I was neither American nor Chinese. I was not Violet nor Vivi nor Zizi. I now lived in an invisible place made of my own dwindling breath, and because no one else could see it, they could not yank me out of it.

How long did my mother stand at the back of the boat? Was it cold on deck? Did she miss the fox wrap she put in my valise? Did she wait until her skin prickled before she went inside? How long did she take to choose a dress for the first dinner at sea? Was it the tulle and lace? How long did she wait in the cabin before she knew no knock would come to her door? How long did she lie awake staring into the pitch-dark? Did she see my face there? Did she see the worst? Did she wait to watch the sun come up or did she stay in bed past noon? How many days did she despair, realizing each wave was one more wave farther from me? How long did it take for the ship to reach San Francisco, to her home? How long by the fastest route? How long by the slowest route? How long did she wait before Teddy was in her arms? How many nights did she dream of me as she slept in her bedroom with the sunny yellow walls? Was the bed still next to a window that was next to a tree with many limbs? How many birds did she count, knowing that was how many I was supposed to see?

How long would it have taken a boat to return? How long by the fastest route, by the slowest route?

How slowly those days went by as I waited to know which route she took. How long it has been since the slowest boats have all come and have all gone.

THE NEXT DAY, I moved into Magic Gourd’s boudoir. I had kept from crying as she packed up her belongings. She held up my mother’s dress and the two rolled-up paintings and asked if she could take them. I nodded. And then she was gone. The only part of my past that remained was Carlotta.

An hour later, Magic Gourd burst in the room. “I am not leaving, after all,” she announced, “thanks to the old bustard’s black fingers.” She had been concocting a plan for two days and proudly unveiled how it unfolded. Just before she left, she met with Mother Ma in the common room to settle her debts. When Mother Ma started doing calculations on the abacus, Magic Gourd raised the alarm.

“‘Ai-ya! Your fingers!’ I said to her. ‘They’ve grown worse, I see. This is terrible. You don’t deserve this misfortune of health.’ The old bustard held up her hands and said the color was due to the liver pills she took. I told her I was relieved to hear this, because I thought it was due to something else and I was going to tell her to try the mercury treatment. Of course, she knew as well as anyone that mercury is used for syphilis. So she said to me: ‘I’ve never had the pox and don’t you be starting rumors that I do.’

“‘Calm down,’ I said to her. ‘My words jumped out of my mouth too soon and only because of a story I just heard about Persimmon. She once worked in the Hall of Tranquility. That was before my time, about twenty years, but you were already here. One of the customers gave her the pox, and she got rid of the sores, but then they came back, and her fingers turned black, just like yours.’

“Mother Ma said she did not know of any courtesan named Persimmon who had worked in the Hall of Tranquility. Of course, she didn’t. I had made her up. I went on to say she was a maid, not a courtesan, so it was no wonder she would not know her by name. I described her as having a persimmon-shaped face, small eyes, broad nose, small mouth. The old bustard insisted her memory was better than mine. But then the clouds of memory lifted. ‘Was she dark-skinned, a plump girl who spoke with a Fujian accent?’

“‘That’s the one!’ I said and went on to tell her that a customer used to go through the back door to use her services for cheap. She needed the money because her husband was an opium sot and her children were starving. Mother Ma and I grumbled a bit about conniving maids. And then I said Persimmon’s customer was a conniver, too. He called himself Commissioner Li and was the secret lover of one of the courtesans. That got the old bustard to sit up straight. It was an open secret among the old courtesans that the old bustard had taken the commissioner as a lover.

“‘Ah, you remember him?’ I said. She tried to show she was not bothered.

“‘He was an important man,’ she said. ‘Everyone knew him.’

“I poked a bit more. ‘He called himself Commissioner,’ I said. ‘But where did he work?’

“And she said, ‘It had something to do with the foreign banks and he was paid a lot of money to advise them.’

“So I said, ‘That’s strange. He told you and no one else that.’

“Then she said, ‘No, no. He didn’t tell me. I heard it from someone else.’

“I made my face look a little doubtful before going on: ‘I wonder who said that. As the rumors go, everyone thought he was too important to question. One of the old courtesans told me that if he had said he was ten meters tall, everyone would have been too afraid to correct him. He sat at the table with his legs wide apart, like this, and wore a scowl on his face, as if he were the duke of sky and mountains.’ That was the way all important men sit, so of course, she could picture him in her mind.

“The old bustard said, ‘Why would I remember that?’

“I sprang my trap. ‘It turns out he was a fake, not a commissioner at all.’

“‘Wah!’ She jumped out of her chair, and then immediately pretended the news meant nothing to her. ‘An insect just bit my leg,’ she said. ‘That’s why I leapt up.’ To improve the lie, she scratched herself.

“I gave her more to scratch: ‘He never came with friends to host his own parties. Remember that? People were expected to invite him to their parties once he arrived. Such an honor! Everyone wanted to please him. In fact, one of the courtesans was so impressed with his title, she gave her goods away, hoping he would make her Mrs. Commissioner. She took him into her boudoir and she never knew he had already stuck himself into Persimmon just before visiting her.’

“The old bustard’s eyes grew really big when I said that. I was beginning to feel a little sorry for her, but I had to go on. ‘And it is even worse than that,’ I said. I told her what I had heard about Commissioner Li, facts she would clearly remember. ‘Whenever he shared this courtesan’s bed, he told her to go ahead and put a full three-dollar charge on his bill—a charge for a party call, even though he had not held a party. He said he did not want her to lose money from spending so much time with him instead of with other suitors. Anyone would think he was generous beyond belief. By the New Year, he owed nearly two hundred dollars. As you know, it’s customary for all clients of the house to settle their accounts that day. He never did. He was the only one. He never showed his face again. Two hundred dollars’ worth of fucks.’

“I saw the old bustard’s mouth was locked into an expression of bitterness. I think she was trying to keep from cursing him. I said what I knew she was thinking: ‘Men like that should have their cocks shrivel up and fall off.’ She nodded vigorously. I went on. ‘People say that the only gift he gave her was syphilitic sores. They assumed he did, since the maid had it—a sore on her mouth, then her cheek, and who knows how many more in places we couldn’t see.’

“The blood drained from the old bustard’s face. She said, ‘Maybe it was the maid’s husband who gave her syphilis.’

“I was not expecting her to come up with this, so I had to think fast. ‘Everyone knew that the old sot could barely lean over the side of his bed to piss. He was a bag of bones. But what difference did it make whether she had it first or he did? In the end, they both had the pox, and everyone figured he must have given it to the courtesan, and she probably did not even know. Persimmon drank mahuang tea all day long, to no avail. When her nipples dripped pus, she covered them in mercury and got very sick. The sores dried up, and she thought she was cured. Six months ago, her hands turned black, and then she died.’

“The old bustard looked as if a pot had fallen on her head. Really, I felt sorry for her, but I had to be ruthless. I had to save myself. Anyway, I didn’t go on, even though I had thought to say that someone learned that the Commissioner of Lies had died of the same black hand disease. I told her that was the reason I had feared for her when I saw her hands. She mumbled that it was not a disease but the cursed liver pills. I gave her a sympathetic look and said we should ask the doctor to check her chi to get rid of this ailment, since those pills were doing no good. Then I went on: ‘I hope no one believes you have the pox. Lies spread faster than you can catch them. And if people see you touching the beauties with your black fingers, they might say the whole house is contaminated. Then the public health bureaucrats will come, everyone will have to be tested, and the house closed down until they verify we are clean. Who wants that? I don’t want someone examining me and getting a peek for free. And even if you’re clean, those bastards are so corrupt, you’ll have to give them money so they don’t hold up the report.’

“I let this news settle in before I said what I had wanted all along. ‘Mother Ma, it just occurred to me that I might help you keep this rumor from starting. Until you correct the balance in the liver, let me serve as Violet’s teacher and attendant. I’ll teach her all the things I know. As you recall, I was one of the top Ten Beauties in my day.’

“The old bustard fell for it. She nodded weakly. For good measure, I said: ‘You can be sure that if the brat needs a beating, I’ll be quick to do it. Whenever you hear her screaming for mercy, you’ll know that I’m making good progress.’

“What do you think of that, Violet? Clever, eh? All you have to do is stand by the door once or twice a day and shout for forgiveness.”

THERE WAS NO single moment when I accepted that I had become a courtesan. I simply fought less against it. I was like someone in prison who was about to be executed. I no longer threw the clothes given to me on the floor. I wore them without protest. When I received summer jackets and pantalets made of a light silk, I was glad for the cool comfort of them. But I took no pleasure in their color or style. The world was dull. I did not know what was happening outside these walls, whether there were still protestors in the streets, whether all the foreigners had been driven away. I was a kidnapped American girl caught in an adventure story in which the latter chapters had been ripped out.

One day, when it was raining hard, Magic Gourd said to me, “Violet, when you were growing up you pretended to be a courtesan. You flirted with customers, lured your favorites. And now you are saying you never imagined you would be one?”

“I’m an American. American girls do not become courtesans.”

“Your mother was the madam of a first-class courtesan house.”

“She was not a courtesan.”

“How do you know that? All the Chinese madams began as courtesans. How else would they learn the business?”

I was nauseated by the thought. She might have been a courtesan—or worse, an ordinary prostitute on one of the boats in the harbor. She was hardly chaste. She took lovers. “She chose her life,” I said at last. “No one told her what to do.”

“How do you know that she chose to enter this life?”

“Mother never would have allowed anyone to force her to do anything,” I said, then thought: Look what she forced on me.

“Do you look down on those who cannot choose what they do in life?”

“I pity them,” I said. I refused to see myself as part of that pitiful lot. I would escape.

“Do you pity me? Can you respect someone you pity?”

“You protect me and I’m grateful.”

“That’s not respect. Do you think we are equals?”

“You and I are different … by race and the country we belong to. We cannot expect the same in life. So we are not equal.”

“You mean I must hope for less than you do.”

“That is not my doing.”

Suddenly, she turned red in the face. “I am no longer less than you! I am more. I can expect more. You will expect less. Do you know how people will see you from now on? Look at my face and think of it as yours. You and I are no better than actors, opera singers, and acrobats. This is now your life. Fate once made you American. Fate took it away. You are the bastard half who was your father—Han, Manchu, Cantonese, whoever he was. You are a flower that will be plucked over and over again. You are now at the bottom of society.”

“I am an American and no one can change that, even if I am held against my will.”

“Oyo! How terrible for poor Violet. She is the only one whose circumstances changed against her will.” She sat down and continued to make chuffing noises as she threw me disgusted looks. “Against her will … You can’t make me! Oyo! Such suffering she’s had. You’re the same as everyone here, because now you have the same worries. Maybe I should do what I promised Mother Ma and beat you until you learn your place.” She fell silent, and I was grateful that her tirade had ended.