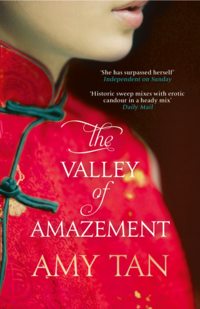

The Valley of Amazement

“Can you see him? Can you smell him?” the flower sisters would ask whenever they caught Magic Cloud looking pleased for no apparent reason.

“Today, just before dusk,” she answered, “I saw his shadow and felt it sweep gently over me.” She drew two fingers up her arm.

And then I, too, saw a shadow and felt a cool sensation sweep across my skin.

“Ah, you feel him, too,” Magic Cloud said.

“No I didn’t. I don’t believe in ghosts.”

“Then why are you scared?”

“I’m not scared. Why should I be? Ghosts don’t exist.” And as if to counter the lie, my fear grew. I recalled Mother telling me that ghosts were manifestations of people’s fear. Why else do these supposed ghosts plague only Chinese people? Despite my mother’s logic, I believed the Poet Ghost still lived in our house. Sudden fear was a sign that he had arrived. But why would he visit me?

The Poet Ghost was at the mock marriage between Billowy Cloud and Prosper Yang, who had signed a contract for three seasons. I learned that Billowy Cloud was sixteen and he was fifty or so. Golden Dove consoled her, saying he would be quite generous, as old men tended to be. And Billowy Cloud said that Prosper Yang loved her and she felt lucky.

My mother was renowned for holding the best weddings of all the courtesan houses. They were Western in style, as opposed to the traditional Chinese weddings for virgin brides, a category to which courtesans could never belong. The courtesan brides even wore a Western white wedding gown, and my mother had a variety the Cloud Beauties could use. The style was clearly Yankee—with low bodices and voluminous skirts, wrapped in glossy gathered silk, and trimmed in lace, embroidery, and seed pearls. Those dresses never would have been confused with the Chinese mourning clothes of rough white sackcloth.

A Western wedding had its advantages, as I had already learned from having attended a Chinese version for a courtesan at another house. For one thing, it did not involve honoring ancestors, who certainly would have disavowed a courtesan as his descendant. So there were no boring rituals or kneeling and endless bowing. The ceremony was short. The prayers were omitted. The bride said “I do” and the groom said “I do.” Then it was time to eat. The banquet food at a Western wedding was also remarkable because all the dishes looked Western but they tasted Chinese.

For different fees, patrons could choose music from among several styles. Yankee music played by a marching band was the most expensive and suitable only during good weather. A Yankee violinist was a cheaper choice. Then there was a choice of music. It was important to not be fooled by the title of a song. One of the courtesans had asked the violinist to play “O Promise Me,” thinking the length of the song would strengthen her patron’s fidelity and perhaps increase the length of the contract. But the song went on for so long that guests lost interest and talked about other matters until the song ended. That was the reason the contract was not renewed, the flower sisters later said. Everyone liked “Auld Lang Syne,” played with the aching power of a Chinese instrument that looked like a miniature two-stringed cello. Even though the tune was sung on sad occasions, such as funerals and farewells, it was still popular. There were only a few English words to learn, and everyone loved to sing them to prove they could speak English. My mother changed the words to reflect a promise of monogamy. If a courtesan broke that promise, it would lead to the end of the contract, as well as a bad reputation that would be hard to overcome. If, however, the patron was the one who broke the promise, the courtesan would feel humiliated. Why had he dishonored her? There must have been a reason.

Prosper, who fancied he was a Chinese Caruso, sang with gusto.

“Should old lovers be forgot,

And never brought to mind!

Should old lovers be forgot,

For a long, long time.

Clang bowls again, my dear old friends,

Clang bowls one more time.

Should old lovers be forgot,

And never come to mind!”

In the middle of the song, I saw Magic Cloud turn her eyes toward the archway. She touched her arm lightly, looked up again, and smiled. A moment later, I felt the familiar coolness blow over my arm and down my spine. I shivered and went to my mother.

Prosper bellowed out the last note and let the clapping go on for too long, and then he called for the gifts to be brought to Billowy Cloud. First came the traditional gift every courtesan received: a silver bracelet and a bolt of silk—a toast to that! The guests raised their cups, tipped their heads back, and downed the wine in one swallow. Next came a Western settee upholstered in pink sateen—two toasts for that! More gifts came. Finally Prosper handed Billowy Cloud what she wanted most, an envelope of money, the first of her monthly stipend. She saw the amount, gasped, and fell speechless as tears streamed down her face. We would not know until later if her tears were because she received more than she had expected or less. Another toast was raised. Billowy Cloud insisted she could not drink another. Her face wore splotches of red and she said she felt the ceiling lurching one way and the floor the other. But Prosper grabbed her chin and forced down the wine, followed immediately by another as his friends egged him on. All at once, Billowy Cloud gurgled and vomited before she collapsed to the floor. Golden Dove quickly signaled the musician for a final song to hurry the guests out of the room, and Prosper left with them, without a glance toward Billowy Cloud, who lay on the floor, babbling apology. Magic Cloud tried to sit her up, but the senseless girl flopped backward like a dead fish. “Bastards,” Golden Dove said. “Put her in a tub and make sure she doesn’t drown.”

I saw many weddings. The younger beauties had contracts one after another, with hardly a week in between. But as they grew older and their eyes sparkled less, there were no more weddings for them. And then came the day when Golden Dove told a beauty she had to “take the sedan,” which was a polite way of saying she was being evicted. I remembered the day that Rosy Cloud was given the bad news. Mother and Golden Dove had her come to the office. I was studying in Boulevard, the room on the other side of the glass French doors. I heard Rosy Cloud’s voice growing louder. Golden Dove was citing figures of money, declining bookings. Why was I able to hear this so clearly? I went to the door and saw that it was not completely closed. There was a half-inch opening. I heard Rosy Cloud beg quietly to stay longer, citing that a certain suitor was on the brink of offering to be her patron. But they held firm and were without sympathy. They suggested another house she might join. Rosy Cloud became loud and angry. They were insulting her, she said, as if she were a common whore. She ran out. A few minutes later I heard her howl in the same way Carlotta did when her foot was caught in the doorjamb, as if her voice was coming from both her bowels and her heart. The sound of it sickened me.

I told Magic Cloud what had happened to Rosy Cloud.

“This will happen to all of us. One day fate brings us here,” she said. “Another day it takes us away. Maybe her next life will be better. Suffer more now, suffer less later.”

“She shouldn’t suffer at all,” I said.

Within three days, a courtesan named Puffy Cloud was in Rosy Cloud’s quarters. She knew nothing of what had gone on in that room—not the bouncing, the sighs, the tears, or the howls.

A few weeks later, I was in Magic Cloud’s boudoir in the late afternoon. Mother had been too busy to eat her late-midday meal with me. She had to dash off to some unknown place to meet an unnamed person. Magic Cloud was putting powder on her face, preparing for a long night—three parties, one at Hidden Jade Path, the other two at houses several blocks away.

I was full of questions. “Are those real pearls?” “Who gave them to you?” “Who will you see tonight?” “Will you bring him to your room?”

She told me that the pearls were the teeth of dragons and a duke had given them to her. He was honoring her tonight, and naturally she would bring him to her room for tea and conversation. I laughed, and she pretended to be offended that I did not believe her.

The next morning she was not in her room. I knew something was wrong because her scholar treasures and silk quilt were missing. I peered into her wardrobe closet. It was empty. Mother was still asleep, as were the courtesans and Golden Dove. So I went to Cracked Egg, the gatekeeper, and he said that he saw her leave but did not know where she had gone. I learned the answer when I overheard two maids talking:

“She was at least five or six years older than she said she was. What house would take an old flower with a ghost stuck inside her?”

“I overheard Lulu Mimi telling the patron it was just superstitious nonsense. He said it didn’t matter if it was a ghost or a living man, it was infidelity and he wanted the contract money back.”

I raced into my mother’s office and found her talking to Golden Dove.

“I know what she did and she’s sorry. You have to let her come back,” I said. Mother said there was nothing more to be done. Everyone knew the rules, and if she made an exception for Magic Cloud, all the beauties might think they could do the same without penalty. She and Golden Dove went back to discussing plans for a large party and how many extra courtesans would be needed.

“Mother, please,” I begged. She ignored me. I burst into tears and shouted: “She was my only friend! If you don’t bring her back, I will have no one who likes me.”

She came to me and drew me close, caressing my head. “Nonsense. You have many friends here. Snowy Cloud—”

“Snowy Cloud doesn’t let me come into her room the way Magic Cloud did.”

“Mrs. Petty’s daughter—”

“She’s silly and boring.”

“You have Carlotta.”

“She’s a cat. She doesn’t talk to me or answer questions.”

She mentioned the names of more girls who were the daughters of her friends, all of whom I now claimed I disliked—and who despised me, which was partially true. I carried on about my friendless state and the danger of my permanent unhappiness. And then I heard her speak in a cold unyielding tone: “Stop this, Violet. I did not remove her for small reasons. She nearly ruined our business. It was a matter of necessity.”

“What did she do?”

“By thinking only of herself, she betrayed us.”

I did not know what betrayed meant. I simply sputtered in frustration: “Who cares if she betrayed us?”

“Your very mother before you cares.”

“Then I will always betray you,” I cried.

She regarded me with an odd expression, and I believed she was about to give in. So I pushed again with my bravado. “I’ll betray you,” I warned.

Her face contorted. “Stop this, Violet, please.”

But I could not stop, even though I knew that I was unleashing an unknown danger. “I’ll always betray you,” I said once more and immediately saw a shadow fall over my mother’s face.

Her hands were shaking and her face was so stiff she appeared to be a different person. She said nothing. The longer the silence grew, the more frightened I became. I would have backed down if I had known what to say or do. So I waited.

At last she turned, and as she walked away, she said in a bitter voice, “If you ever betray me, I shall have nothing to do with you. I promise you that.”

MY MOTHER HAD a certain phrase she used with every guest, Chinese or Western. She would walk hurriedly to a certain man and whisper excitedly, “You’re just the one I hoped to see.” Then followed the dip of her head toward the man’s ear to whisper some secret, which caused the man to nod vigorously. Some kissed her hand. This repeated phrase distressed me. I had noticed that she was often too busy to pay any attention to me. She no longer played the guessing games or sent me on treasure hunts. We no longer lay in her bed cuddled next to each other as she read the newspaper. She was too busy for that. Her gaiety and smiles were now reserved for the men at her parties. They were the ones she had hoped to see.

One night, as I crossed the salon with Carlotta in my arms, I heard Mother call out: “Violet! You’re here. You’re just the one I hoped to see.”

At last! I had been chosen. She gave profuse apologies to the man she had been conversing with, citing that her daughter required her urgent attention. What was so urgent? It did not matter. I was excited to hear the secret she had saved for me. “Let’s go over there,” Mother said, nudging me toward a dark corner of the room. She took my arm in hers, and we were off at a brisk pace. I was telling her about Carlotta’s latest antics, something to amuse her, when she let go of my arm, and said, “Thank you, darling.” She walked over to a man in the corner of the room and said, “Fairweather, my dear. I’m sorry I was delayed.” Her dark-haired lover stepped out of the shadows and kissed her hand with fake gallantry. She returned a crinkle-eyed smile I had never seen her give to me.

I could not breathe, crushed by my short-lived happiness. She had used me as her pawn! Worse, she had done so for Fairweather, a man who had visited her from time to time, and whom I had always disliked. I had once believed I was the most important person in her life. But in recent months, that was disproved. Our special closeness had become unmoored. She was always too busy to spend time chatting with me during her midday meals. Instead she and Golden Dove used that hour to discuss the evening plans. She seldom asked me about my lessons or what I was reading. She called me “darling,” but she said the same to many men. She kissed my cheek in the morning and my forehead at night. But she kissed many men, and some on the mouth. She said she loved me, but I did not see any particular sign of that. I could not feel anything in my heart but the loss of her love. She had changed toward me, and I was certain that it had started the day when I threatened to betray her. Bit by bit, she was having nothing to do with me.

Golden Dove found me crying one day in Boulevard. “Mother does not love me anymore.”

“Nonsense. Your mother loves you a great deal. Why else does she let you go unpunished for all the naughty things you do? Just the other day, you broke a clock by moving its hands backward. You ruined a pair of her stockings by using it as a mouse for Carlotta to chase.”

“That’s not love,” I said. “She didn’t get mad because she doesn’t care about those things. If she truly loved me, she would prove it.”

“How?” Golden Dove asked. “What is there to prove?”

I was thrown into mute confusion. I did not know what love was. All I knew was a gnawing need for her attention and assurances. I wanted to feel without worry that I was more important than anyone else in her life. When I thought about it further, I realized she had given more attention to the beauties than to me. She had spent more time with Golden Dove. She had risen before noon to have lunch with her friends, the bosomy opera singer, the traveling widow, and the French lady spy. She had devoted much more attention to her customers than to anybody else. What love had they received that she had not given me?

That night I overheard a maid in the corridor telling another that she was worried sick because her three-year-old daughter had a high fever. The next night, she announced happily that her daughter had recovered. In the afternoon of the next day, the woman’s screams reverberated in the courtyard. A relative had come to say her child had died. She wailed, “How can that be? I held her this morning. I combed her hair.” In between her sobs, she described her daughter’s big eyes, the way she always turned her head to listen to her, how musical her laughter was. She babbled that she was saving money to buy her a jacket, that she had bought a turnip for a healthy soup. Later she moaned that she wanted to die to be with her daughter. Who else did she have to live for? I cried secretly as I listened to her grief. If I died, would Mother feel the same about me? I cried harder, knowing she would not.

A week after Mother had tricked me, she came into the room where I was studying with my tutor. It was only eleven, an hour before she usually rose from bed. I gave her my sullen face. She asked if I would like to have lunch with her at the new French restaurant on Great Western Road. I was wary. I asked her who else would be there.

”Just the two of us,” she replied. “It’s your birthday.”

I had forgotten. No one celebrated birthdays in the house. It was not a Chinese custom, and Mother had not made it hers. My birthday usually occurred near the Chinese New Year, and that was what we celebrated, with everyone. I tried to not be too excited, but a surge of joy went through me. I went to my room to put on a nice day dress, one that had not been snagged by Carlotta’s claws. I selected a blue coat and a hat of a similar color. I put on a grown-up pair of walking shoes of shiny leather that laced up to my ankles. I saw myself in the long oval mirror. I looked different, nervous, and worried. I was now eight, no longer the innocent little girl who trusted her feelings. I had once expected happiness and lately had received only disappointments, one after the other. I now expected disappointment and prayed to be proven wrong.

When I went to Mother’s study, I found that Golden Dove and she were laying out the tasks for the day. She was walking back and forth in her wrapper, her hair unbound.

“The old tax collector is coming tonight,” Mother was saying. “He promises that some extra attention may make him inattentive to my tax bill. We’ll see if the old dog fart is telling the truth this time.”

“I’ll send a call chit to Crimson,” Golden Dove said, “the courtesan at the Hall of Verdant Peace. She’ll take any kind of business these days. I’ll advise her to wear dark colors, dark blue. Pink is unflattering on someone well past youth. She should know better. I’ll also tell the cook to make the fish you like, but not with the American flavors. I know he wants to please you, but it never comes out right, and we all suffer.”

“Do you have the list for tonight’s guests?” Mother said. “I don’t want the importer from Smythe and Dixon to come anymore. None of his information has been reliable. He’s been sniffing around to get something for nothing. We’ll give his name to Cracked Egg so he does not get past the gate …”

By the time she and Golden Dove finished, it was nearly one. She left me in the office and went to her room to change into a dress. I wandered around her office, and Carlotta followed me, rubbing against my legs wherever I stood. A round table was cluttered with knickknacks, the sorts of gifts some of her admirers gave her, not knowing she preferred money. Golden Dove sold the knickknacks she did not want. I picked up each object, and Carlotta jumped up and sniffed. An amber egg with a bug inside—that one would certainly go. An amethyst-and-jade bird—she might keep that. A glass display case of butterflies from different lands—she must hate that one. A painting of a green parrot—I liked it, but the only paintings Mother put on the walls were nude Greek gods and goddesses. I turned the pages of an illustrated book called The World of the Sea and saw illustrations of hideous creatures. I used a nearby magnifying glass to enlarge the titles of books in the bookcase: The Religions of India, Travels to Japan and China, China in Convulsion. I came across a red-covered book embossed with the black silhouette of a boy in uniform shooting a rifle. Under the Allied Flags: A Boxer Story. A note was stuck in the middle of the pages. It was written in the careful script of a schoolboy.

My dear Miss Minturn,

If ever you need an American lad who knows how to obey orders, will you consider using me as volunteer aide? I’d like to make myself as useful as you desire.

Your faithful servant,

Ned Peaver

Had Mother accepted his offer to be her faithful servant? I read the page where the note had been inserted. It was about a soldier named Ned Peaver—aha!—during the Boxer Rebellion. After a quick glance at the page, I concluded Ned was a dull, prissy boy, who always followed orders. I had always disliked anything to do with the Boxer Rebellion. I was two years old in 1900 when the worst of the rebellion took place, and I believed I could have died in the violence. I had read a book about young men who swore themselves into the brotherhood of Boxers when millions of peasants in the middle of China were starving due to a flood one year, and a drought the next. When they heard rumors that foreigners were going to be given their land, they killed about two hundred white missionaries and their children. By one account, a brave little girl sang sweetly as her parents watched her being sent by the whack of a sword to heaven. Whenever I pictured it, I touched my soft throat and swallowed hard.

I looked at the clock. Its newly repaired hands said it was now two o’clock. I had been waiting nearly three hours since she announced we would have lunch. All at once, my head and heart exploded. I ripped up Ned Peaver’s letter. I went to the table with my mother’s plunder and hurled the case of butterflies onto the floor. Carlotta ran off. I threw down the amethyst bird, the magnifying glass, the amber egg. I tore off the cover of The World of the Sea. Golden Dove ran in and looked at the mess, horrified. “Why do you hurt her?” she said mournfully. “Why is your temper so bad?”

“It’s two o’clock. She said she was taking me to a restaurant for my birthday. Now she’s not coming. She didn’t remember. She always forgets I’m even here.” My eyes were blurry with tears. “She doesn’t love me. She loves all those men.”

Golden Dove picked up the amber egg and magnifying glass. “These were your gifts.”

“Those are things that men gave her and she doesn’t want.”

“How can you think that? She chose them just for you.”

“Why didn’t she come back to take me to lunch?”

“Ai-ya! You did this because you’re hungry? All you had to do was ask the maid to bring you something to eat.”

I did not know how to explain what the outing to the restaurant had meant to me. I blurted a jumble of wounds: “She tells the men that they are the ones she wants to see. She told me the same, but it was a trick. She doesn’t worry anymore when I’m sad or lonely …”

Golden Dove frowned. “Your mother spoils you, and this is the result. You have no gratitude, only a temper when you do not get your way.”

“She didn’t keep her promise and she didn’t say she was sorry.”

“She was upset. She got a letter—”

“She gets many letters.” I kicked at the confetti of Ned’s note.

“This letter was different.” She stared at me in an odd way. “It was about your father. He’s dead.”

I did not understand what she had said at first. My father. What did that mean? I was five when I first asked Mother where my father was. Everyone had one, I learned, even the courtesans whose fathers had sold them. Mother told me that I had no father. When I pressed her, she said that he had died before I was born. Over the next three years, I pressed Mother from time to time to tell me who my father was.

“What does it matter?” she always said. “He’s dead, and it was so very long ago I’ve even forgotten his name and what he looked like.”

How could she have forgotten his name? Would she forget mine if I died? I pestered her for answers. When she grew quiet and frowned, I sensed it was dangerous to continue.